One of the most outrageous obsessions by the mainstream is to substitute statistics for human action then apply political correctness when interpreting them.

This Wall Street Journal Blog should be an example (bold highlights mine)

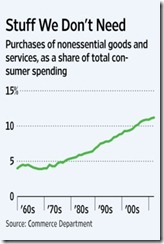

As it turns out, quite a lot. A non-scientific study of Commerce Department data suggests that in February, U.S. consumers spent an annualized $1.2 trillion on non-essential stuff including pleasure boats, jewelry, booze, gambling and candy. That’s 11.2% of total consumer spending, up from 9.3% a decade earlier and only 4% in 1959, adjusted for inflation. In February, spending on non-essential stuff was up an inflation-adjusted 3.3% from a year earlier, compared to 2.4% for essential stuff such as food, housing and medicine.

To be sure, different people can have different ideas of what should be considered essential. Still, the estimate is probably low. It doesn’t, for example, account for the added cost of certain luxury items such as superfast cars and big houses.

Interestingly, people who spend more on luxuries have experienced less inflation. As of February, the weighted average price of non-essential goods and services was up only 0.2% from a year earlier and 82% from January 1959, according to the Commerce Department. By contrast, the cost of all consumer goods was up 1.6% from a year earlier and 520% from January 1959.

The sheer volume of non-essential spending offers fodder for various conclusions. For one, it could be seen as evidence of the triumph of modern capitalism in raising living standards. We enjoy so much leisure and consume so much extra stuff that even a deep depression wouldn’t – in aggregate — cut into the basics.

Alternately, it could be read as a sign that U.S. economic growth relies too heavily on stimulating demand for stuff people don’t really need, to the detriment of public goods such as health and education. By that logic, a consumption tax – like the value-added taxes common throughout Europe—could go a long way toward restoring balance.

It’s absurd to say that we buy stuff which we don’t need.

While the author does say “different people can have different ideas of what should be considered essential”, he seems confused on why people engage in trade at all.

Moreover, saying that Americans "buy stuffs they don’t need" translates to an ethical issue with political undertones: the author seems to suggest that Americans have wrong priorities or have distorted set of choices! Of course the implication is that only the government (and the author) knows what are the stuffs which people truly needs, thus his justification for a consumption tax! (Put up a strawman then knock them down!)

Although the author attempts to neutralize the political flavor of his article by adding an escape clause: that the stats signify as “evidence of the triumph of modern capitalism in raising living standards”.

People buy to express their demonstrated preference. Yet such preference gets screened from a set of given ordinal alternatives (e.g., 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc..) from which the individual makes a choice or a decision. And that choice (buying) constitutes part of human action.

As Professor Ludwig von Mises explained, (bold highlights mine)

Action is an attempt to substitute a more satisfactory state of affairs for a less satisfactory one. We call such a willfully induced alteration an exchange. A less desirable condition is bartered for a more desirable. What gratifies less is abandoned in order to attain something that pleases more. That which is abandoned is called the price paid for the attainment of the end sought. The value of the price paid is called costs. Costs are equal to the value attached to the satisfaction which one must forego in order to attain the end aimed at.

If I buy beer (1st order) at this moment at the cost of my other alternatives: a steak (2nd order) or a chocolate (3rd order), does my choice for beer represent stuff I don’t need?

The instance that I made a sacrifice (steak and chocolate) to make a choice (beer) makes my decision part of my act to fill a personal unease or a “need”.

It may not be your need, but it is mine. My actions reflect on my preference to solve my need.

The fact that beer is produced and sold implies that it is an economically valuable product (estimated at $325 billion industry for the world for 2008). Many people “needs” it and would pay (hard earned or otherwise) money for it.

The difference lies in the values ascribed to it by different consumers.

Some see beer as a way to socialize, or a way to get entertained or to get promoted or to close deals or as stress relief or a part of the ancillary rituals for other social activities or for many other reasons as health.

Some may not like beer at all!

The point is people consume or don’t consume beer for different reasons. As an economic good, beer is just part of the ordinal alternatives for people to choose from, aside from chocolate or steak or other goods or services.

Suggesting that beer isn’t a stuff we need, as a beer consumer, severely underappreciates the way we live as humans.

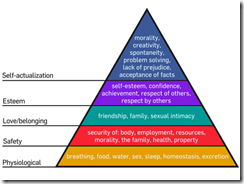

Abraham Maslow proposed that human needs come in the form of a pyramid. He breaks them down into 5, namely physiological, safety, social (love and belonging), esteem and self-actualization.

As the Wikipedia explains, (bold highlight mine)

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is often portrayed in the shape of a pyramid, with the largest and most fundamental levels of needs at the bottom, and the need for self-actualization at the top.

The most fundamental and basic four layers of the pyramid contain what Maslow called "deficiency needs" or "d-needs": esteem , friendship and love, security, and physical needs. With the exception of the most fundamental (physiological) needs, if these "deficiency needs" are not met, the body gives no physical indication but the individual feels anxious and tense. Maslow's theory suggests that the most basic level of needs must be met before the individual will strongly desire (or focus motivation upon) the secondary or higher level needs. Maslow also coined the term Metamotivation to describe the motivation of people who go beyond the scope of the basic needs and strive for constant betterment Metamotivated people are driven by B-needs (Being Needs), instead of deficiency needs (D-Needs).

From my example, my choice for a beer may not signify a physiological (basic need), yet they could reflect on my other deficiency needs (emotion or esteem or social needs).

In other words, B (being)-needs may not be D (deficiency)-needs but they still represent as human ‘intangible’ NEEDS.

Bottom line:

Statistics, which accounts for mainstream’s obsessions, fails to incorporate the intangible or non-material aspects of human nature.

It is, thus, misleading to make the impression that by reducing people’s activities to quantitative equations, or to dollar and cents, patterned after physical sciences, governments can manage society efficiently.

As the great Friedrich von Hayek admonished, in his Nobel lecture “the Pretence of Knowledge” (bold highlights mine)

While in the physical sciences it is generally assumed, probably with good reason, that any important factor which determines the observed events will itself be directly observable and measurable, in the study of such complex phenomena as the market, which depend on the actions of many individuals, all the circumstances which will determine the outcome of a process, for reasons which I shall explain later, will hardly ever be fully known or measurable. And while in the physical sciences the investigator will be able to measure what, on the basis of a prima facie theory, he thinks important, in the social sciences often that is treated as important which happens to be accessible to measurement. This is sometimes carried to the point where it is demanded that our theories must be formulated in such terms that they refer only to measurable magnitudes.

Lastly the notion that people don’t know of their priorities seems plain silly and downright sanctimonious.

Besides, governments compose of people too which makes the whole quantitative statistical exercise as self-contradictory.

No comments:

Post a Comment