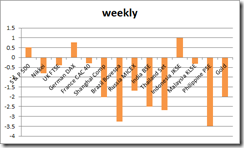

The Phsix lost 3.5% this week, the largest among the regional contemporaries.

Except for Indonesia, Asia, the BRIC and Indonesia have largely been in the red.

In the meantime, US and European stocks remain turbocharged and on a Wile E. Coyote momentum.

This week’s marked decline by the Phisix and the SET seems to reinforce the fourth downside arc of the Nikkei.

I am not in a position to guess whether the coming week will herald continued decline or a rebound, although if we should approximate on the Nikkei’s post bust consolidation pattern, any further decline would equally be met with a limited rebound. And the rangebound phase can be expected to continue perhaps until the first or second quarter of 2014 before a major move.

But this would be conditional to a pattern repetition.

As a side comment, as I have previously pointed out[2], the Philippines shares the same “supply-side” imbalances as with Japan’s bubble dynamics prior to the bust. There even have been similarities in foreign currency reserves and current account surpluses. Yet despite the huge savings and the NIIP complimenting on the substantial forex reserves and current account surpluses, these much touted advantages eventually had been overwhelmed by the basic laws of economics. Credit fuelled boom turned into a massive banking and property bust. Yet the bubble bust hangover continues to linger twenty three years (Japan’s lost two decades) and counting. And the desperation from the deepening frustration of the inability by the Japanese economy to break-away from the seemingly perpetual malaise has forced incumbent policymakers to undertake the grandest central bank experiment—Abenomics or doubling of the money base in two years—which is virtually doing the same thing over and over again but at a bigger scale but expecting different results.

And absent big economic or financial news, the current weakness by domestic stocks has been impelled by net foreign selling. For the past 3 weeks, the Philippine Stock Exchange registered consecutive net selling of Php 4.6, Php .7 and Php 3 billion.

Why?

Let move to hypotheticals. Let me put on the hat of a US or European investor and see how Philippine assets should fare with my prospective portfolio

The Unsustainable Convergence Trade

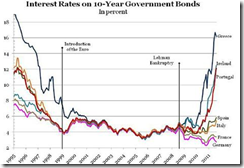

As of Friday, with 10 year yields at 3.53% for the Philippines and 1.76% for Germany, the yield spread has narrowed to a landmark 177 basis points from about 400 to 500 basis points in 2010. Incredible.

The same historic convergence can be seen between 10 year US Treasury notes and the Philippine counterpart. As of Friday’s close, the spread between UST which closed at 2.751% and the Philippines has been at an astounding 78 basis points that’s from about 400-450 basis points in 2012.

Based on Tradingeconomics.com[3] categorization of yield where the “yield required by investors to loan funds to governments reflects inflation expectations and the likelihood that the debt will be repaid”, the narrowing spreads has been premised from the belief that the Philippines will be immune from the global bond vigilantes and or from the belief that the Philippines will proximate (soon) the economic status of developed economies such as the US, Germany, Singapore or Hong Kong in terms of creditworthiness or capacity to pay debt

Unless one shares such ridiculous beliefs, there hardly seems any upside room for Philippine 10 year bonds.

Has anyone ever given a thought how the Philippines, with a per capita income of $4,410 (2012 World Bank), would be able to approximate the US $49,965 or Germany US $40, 901 in terms of “the likelihood that the debt will be repaid” as previously discussed[4]?

True the US has unwieldy debts but they have a currency, the US dollar, which has functioned as the de facto currency reserve of the world[5], which for now gives them the upper hand or the space to finance such intractable debts.

Per capita GDP[6] of the US represents 11.32x the Philippines, yet bond markets are presupposing that the Philippines will narrow the gap substantially soon (!!).

And if one were to use New Zealand’s bond equivalent as benchmark, which closed Friday with a 4.67% yield (meaning New Zealand has been priced as less creditworthy than the Philippines) and whose per capita income has been $32,219 (2012 World Bank), then the implication is that Philippine bond market have priced Philippine per capita GDP to explode by over 7.3x and surpass New Zealand.

Yet how will we attain this? Pump up bigger bubbles?

This is like saying 80+ PE ratio of the US Russell 2000 small cap index[7] is considered ‘cheap’ and thus a buy! It’s the kind of euphoria that espouses on a “this time is different” outlook.

Philippine bond markets have been grotesquely mispriced.

The Eurozone’s Convergence Bubble Trade as Paradigm

We have seen this kind of interest rate convergence before.

The introduction of the euro led to a near synchronous convergence of interest rates acrossf Euro members[8]. Such convergence inflated domestic bubbles fuelled by domestic credit which was aggravated by capital flows from the core (Germany, France) to the periphery (Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Greece).

Associate Professor at the Universidad Rey Carlos and associate scholar of the Mises Institute Philipp Bagus explains[9]

The lower interest rates coupled with an expansionary monetary policy by the ECB led to distortions in peripheral economies. The Greek government used the lower interest rate to build a public adventure park. Italy delayed necessary privatizations. Spain expanded the public sector and built a housing bubble. Ireland added to their housing bubble a financial bubble. These distortions were partially caused by the EMU interest-rate convergence and the expansionary policies of the ECB. Naturally, people related to the bubble activities in these countries — such as public employees and construction workers — benefited. However, the population in general took a loss through the extension of the public sector and reduction of the private sector, as well as through malinvestments in the construction industry.

Well, I hardly see any difference then and now…

This is the update of the credit boom that has fuelled a Philippine version of public sector “infrastructure” spending boom and a property bubble induced by the interest rate convergence.

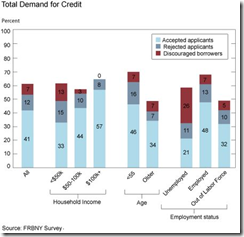

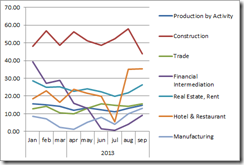

Credit growth has once again reaccelerated, particularly to what I call as bubble areas.

BSP data as of September[10] reveals that general banking loans advanced to 14.84% (year on year) surpassing the March levels and is at a breath away from the January 2013 high of 15.64%. The major push comes from a sharp upside recovery from Real Estate, Rent & Business Services which was up 26.46% (y-o-y) and accounts for the second best month after January’s 28.53 (y-o-y). Real estate loans accounted for 21.15% of loans issued by the banking industry.

Financial intermediation more than doubled to 9.03% (y-o-y) compared to last month’s 4.09%. Part of this doubling of financial intermediation growth must have spilled over to the post August low rebound of the Phisix which returned 1.9% for September.

Loans to the Hotel and Restaurant and Trade (wholesale and retail) remain robust at 35.46% and 15.51% respectively. Meanwhile loans to the construction sector fell to a still amazing 43.72% as against 58.03% last month.

These bubble sectors constitute about half or 50.1% of total loans by the banking industry in September.

Also the impact from World Bank IFC’s Doing Business reforms[11] in the easing of construction permits (based on June 2012-May 2013 survey) appears to have taken effect. Reforms appear to be based on lobbying by the property-financial sector. Such reforms, including guaranteeing borrowers’ right to access their data reveal of the skewed economic priorities of the current administration in accommodating bubbles.

Loans to the manufacturing, a non-bubble area so far, likewise ballooned by 13.1%. Manufacturing loans accounted for an 18.58% share of total banking production side loans last September.

Consumer loans, where only a few households have access to, grew by only 10.91% over the month.

The surge in banking loans was equally reflected on domestic liquidity or M3 which grew by 31% year on year[12].

So the BSP will achieve a $32k per capita income by continually inflating of bubbles via a massive build-up of debt or by borrowing tomorrow’s spending today.

This also means that statistical economic growth for the third quarter will likely remain at 7% or above.

Yet if I am a foreign investor, in the realization that domestic bonds have been flagrantly mispriced, economic growth have been reflected on statistics rather than the real economy and a persistently growing imbalance between the supply side and the demand side financed by a sustained asymmetric build-up on debt all dependent on the Fed’s easy money policy, the potential returns on Philippine investments hardly justifies the risk spectrum from converging yield spreads in terms of credit risk, currency risk, inflation risk, interest rate risk and the market risk.

China’s Hissing Bubble as Potential Spoiler to the Convergence Trade

And I don’t need to look at the West to realize of potential risks from the outlandish convergence trade.

Last week’s considerable improvement in China’s export data[13], proposed reforms on the Third Plenum[14] and liberalization of the bond markets via the stock market[15] failed to inspire Chinese stock markets to rally. The Shanghai index sank 2.02% this week.

One can understand why. While Shibor (short term interbank lending) rates have partially been soothed, rampaging bond vigilantes can be seen in the yields of China’s 10 year bonds which has spiked to 4.27% as of Friday the highest level since November 2007[16].

While ascendant yields of Chinese 10 year bonds will affect lending rates of domestic debt, a seeming return of the bond vigilantes in the US, the UK, Germany and France will impact soaring China’s foreign debt exposure

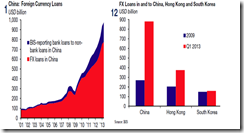

The Institute of International Finance (IIF), the world's only global association or trade group of financial institutions with over 450 members which includes banks and financial houses[17], notes of a new study by the Bank of International Settlements where FX loans to China's corporations have more than tripled from $270 billion in 2009 to $880 billion in March 2013.

The surge of FX loans can also be seen in Hong Kong $375 billion and Korea $160 billion[18]

Bond vigilantes will not only put a dent on a debt dependent statistical economic growth, the bond vigilantes will put into question credit quality of outsized debts from the private sector to the government.

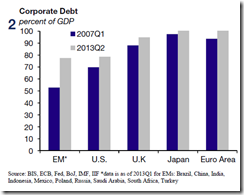

Importantly, emerging markets have outpaced corporate debt growing everywhere. “Corporate indebtedness has increased across the world” according to the cartel of global financial institutions, the IIF.

The IIF seems worried about bubbles too, “after six years of abundant liquidity and near-zero policy rates, additional easing of monetary conditions, justifiable as it is in the case of the Euro Area and Japan, could increasingly lead to financial distortions and pockets of bubbles in asset markets”

Distortions fueling “pocket of bubbles” have been a laughable understatement, but of course, what can one expect from the key beneficiaries of bubbles.

Momentum Trades; The Stock Market Returns and Economic Growth

Third, if I am a foreign momentum or yield chaser, I wouldn’t pile on Philippine stocks but rather on US and European markets.

Since the reinvigorated bond vigilantes rationalized by the Taper Talk last May, the Phisix has vastly underperformed US and European markets (via the blue chip Stoxx 50). Given the shared characteristics of Thailand’s SET with the Phisix, the SET will also reflect on the PSEC’s underperformance

And since I expect the bond vigilantes to continue with their growing incidences of raids on the international financial markets, the trend seems to favor a sustained underperformance by the Phisix-SET.

Finally as foreign investor, despite media’s hullabaloo over Philippine growth story, the reality is that statistical growth has hardly been related with stock market performance.

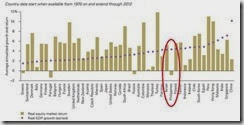

The investing giant, the John Bogle founded Vanguard group identifies weak correlation between real stock market performance and real GDP across the 46 countries.

From 1970-2012 real returns by the Phisix has been NEGATIVE despite the recent boom. I would add that considering suppression of inflation rates and constant changes in the Phisix components favouring the high flyers, real returns based on original construct must be even lower.

But it is not just the Phisix, real GDP growth has been relatively uncorrelated with stock market returns.

As the Vanguard notes[19]

Growth expectations, globalization, financial deepening, and valuation levels all play significant roles in disconnecting long-term growth outcomes from equity market returns

I may add that central bank policies have sharply reduced such correlation. By punishing savers and rewarding speculation via Zero bound rates and QEs, redistribution of resources tilted towards stock markets has increased the disconnection between the real economy and financial performance. Overall such price distortions are signs of bubbles.

Given the uncertainty brought about by bond vigilantes, popularly expressed via the Taper Talk (which is only half true) a serious foreign investor would question the sustainability of the convergence trade and doubt the relationship between real stock market returns relative to GDP growth, while a momentum player will prefer US and European stocks.

Foreigners Determine Returns of the Phisix

This brings us to the role played by foreigners.

Three facts to consider

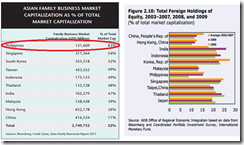

-Publicly listed firms in the Philippines remain largely family businesses where the elites control 83% of the total market cap as of 2011 (left table)

-Retail investors remain insignificant players in terms of numbers. Amount is uncertain.

96.4% of the 525,850 accounts[20] in the Philippine Stock Exchange have been identified as retail, 3.6% institutional, 98.5% local investors. Online accounts represent 14.9% of total. Retail investors include members of the economic elite.

Despite the 432% jump by the Phisix from October 2008, to May 2013, new accounts grew by only 22% or a CAGR of 4.07%

-The gap between family owned % share of the market cap and retail investors have been filled by foreigners. Foreign investors as of 2009 accounts about 16% share of market cap (right window)[21]

Unless there will be a major change in the present dynamics, this leaves foreigners as the critical participants instrumental in determining the path of the Phisix.

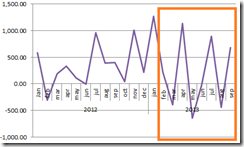

Since the historic convergence trade or the significant narrowing of yield spreads between the US Treasuries/German Bunds and Philippine bonds, the flow of foreign money has been sharply volatile according to BSP data[22].

And despite a seemingly steady low bond yields, the Philippine Peso seem to reflect on the volatility of the Phisix and of the foreign portfolio flows.

Scroll back up to see how narrowing yields has coincided with the Phisix-Peso tempest

In short, Philippine bonds look like the odd man out.

As foreigner, Philippine assets will hardly be appealing mainly due to the lack of margin of safety.