14.66% in 8 straight weeks of unwavering ascent has truly been spectacular!!

Whether parabolic or vertical, the Phisix seems to have gone ballistic.

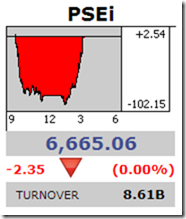

February has already racked up 6.8% with this week’s 2.2% gains. Yet there are still four trading days to go.

As I said last week, should 7% return per month persist, then the Phisix 10,000 will be reached within the second semester of this year.

Again I am NOT saying it will, but we cannot discount the likelihood of such event, considering what appears to be the deepening of the manic phase in the Philippine Stock Exchange.

Signs of Mania: Friday’s Marking the Close

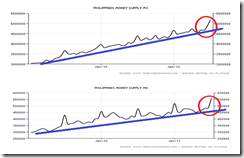

I highlighted this week’s actions (via red ellipse) because of what appears to be a botched attempt by the Phisix to correct.

In what appears to be a sympathy move with US markets which closed lower Thursday, on Friday, the Phisix has been down through most of the session, by about 1.5% (chart from technistock). That’s until the last few minutes before the closing bell window, where the losses had precipitately been wiped out to close the day almost unchanged (or a fraction lower)

Whether what seems as “marking the close” has been another attempt “manipulate” the Phisix for whatever ends (I would suggest political), or that bulls have taken the opportunity to conduct a massive counterstrike against the bears, such refusal to allow for a normal profit taking mode simply has been an expression of the intensifying du jour bullish frenzy.

Net foreign activity posted marginal selling last Friday (Php 36 million). Index heavyweights exhibited mixed performance in terms of foreign activity, which may suggest that local buying could have been mostly responsible for the last minute rebound.

To boost the Phisix means to bid up major blue chip issues. This requires heavy Peso firepower that can emanate mostly from institutions rather than from retail participants, regardless of nationality, whether foreign or local.

The scale of actions from Friday reflects on either hugely expanded risk appetite or the increasing symptoms of desperation to chase momentum from so-called professional money managers, or that parties responsible for Friday’s action could have been conducted by largely price insensitive taxpayer financed institutions.

Yet given the current election season and perhaps the desire to generate upgrades in the nation’s credit rating in order to justify political spending binges, one cannot discount on the potential influences played by public institutions in the stoking of today’s frenetic markets.

To elaborate, marking the close is the practice of buying a security at the very end of the trading day at a significantly higher price[1] is considered illegal by Philippine statutes[2]. Although personally speaking, I consider insider trading[3] and related rules and regulations as arbitrary, repressive, unequal and immoral form of laws.

For instance, the legality or illegality of what appears as “marking the close” could depend on the identity or of the class of executor/s. If public institutions may have been involved, then I doubt if such regulations will apply or will be enforced. Such rules get activated only when there has been a public outcry or when authorities want to be seen as doing something or when used for assorted political goals.

Either way, yield chasing or politically motivated actions to artificially prop markets arrive at a similar conclusion: a policy induced mania.

Mounting Publicity Hysteria

Of course, the manic phases are essentially reinforced through public’s psychology. The public has been made to believe that prices represent reality which tells of the perpetual extension of such boom. Such resonates on the mentality that “this time is different”: the four most dangerous words of investing, according to the late legendary investor John Templeton

Hysteria about the boom phase has been building up.

Proof?

This Bloomberg article entitled “Philippines Trounces Global Stocks in Aquino-Led Rally[4]”, even sees the current rally as “structural”.

I wonder how valid will the “structural” foundations of this bull market be when faced with significantly higher interest rates.

Nevertheless it is a fact that the Philippines have “trounced” the world in terms of returns.

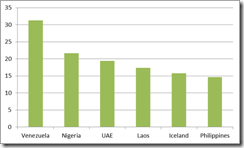

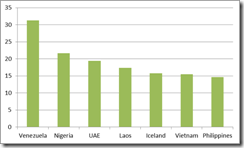

In my radar screen of the equity benchmarks of 83 nations, on a year-to-date basis Venezuela’s Caracas Index has been on the top of the list, with an astronomical 31% nominal currency gains which essentially compounds on 2012’s stratospheric 302%.

Yet as I have repeatedly been pointing out[5], what seem as rip-roaring stock market gains are in fact an illusion.

Venezuela has most likely been suffering from seminal stages of hyperinflation, where the stock market becomes a shock absorber or a lightning rod of a massively devalued or inflated currency. Venezuela’s recent official devaluation by 32% has only triggered a steeper fall in the unofficial rate of her currency, the bolivar.

The official rate has been recently readjusted to 6.3 bolivar per US dollar, but the black market for the bolivar trading has been trading at around 22 per US dollar[6] from 19 less than two weeks back[7]. As typical symptom of hyperinflationary episodes, Venezuela has been suffering from widespread shortages of goods.

Venezuela’s skyrocketing stock market from hyperinflation has been reminiscent of Zimbabwe in 2008. In 2008, as the world plumbed to the nadir as consequence to the contagion effects from the US housing bubble bust, Zimbabwe became the top performer, nominally speaking.

Yet Kyle Bass, a prominent hedge manager, captures the zeitgeist of such a boom[8] (italics added)

One of the best performing equity markets in the last decade has been Zimbabwe. But now your entire equity portfolio only buys you three eggs.

Yes, thousands of percent in returns buys you three eggs.

This shows how stock markets, as surrogate or as representative of real assets, serve as refuge to monetary inflation. This has been especially elaborate at the extremes—hyperinflation.

This also implies that monetary inflation, which has been neglected by the mainstream, plays a very important role in establishing price levels of the equity markets.

Outside Venezuela, the rest of the top ranked equity bellwethers have been far beyond their respective nominal record highs. This makes the local equity bellwether, the Phisix, the likely global crown holder or the current world champion. The Manny Pacquiao of international stock markets. The $64 trillion question is its sustainability.

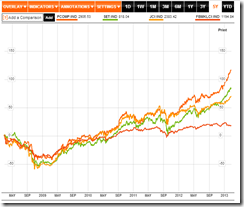

From Friday’s close, the Phisix has been up 256% since the last trading day of 2008. This translates to around 35% CAGR.

Even among the top ASEAN peers, from a 5-year perspective or from a starting point in mid-2008 from the Bloomberg chart, the Phisix [PCOMP: red orange] has outclassed by a widening margin, Thailand [SET: Green], Indonesia [JCI: orange] and Malaysia [FBMKLCI: red].

So the feedback loop between prices and media cheerleading entrenches the public’s belief and conviction of the flawed views of realty. Such perceptions translate to actions: more debt.

Bubble Mentality Leads to Bubble Actions

As I have pointed out last week, manias signify as the stage of the bubble cycle where the yield chasing phenomenon has become the prevailing bias. Manias are essentially underpinned by voguish themes unquestioningly embraced by the public and most importantly enabled, facilitated and financed by credit expansion.

I pointed out how the booming stock markets have reflected on the growing imbalances in the real economy of the Philippines

The stock market boom has similarly been reinforced by the expansion of credit at exactly where such imbalances have been progressing: property-finance-trade, or simply, the property-shopping mall-stock market bubble.

Such extraordinary growth in credit may have already percolated into the domestic money supply

The monetary aggregate, M3 or as per BSP definition[9], constitutes currency in circulation, peso demand deposits, peso savings and time deposits plus peso deposit substitutes, such as promissory notes and commercial papers, has jumped by 16.22% in 2012. From 2008 CAGR for M3 has been at 11.51%.

On the other hand, M0 or narrow money or as per tradingeconomics.com[10], the most liquid measure of the money supply including coins and notes in circulation and other assets that are easily convertible into cash, spiked by 24% in 2012, which on a 5 year basis grew by 13.2% CAGR.

Although there have been many intermittent instances of peculiar outgrowth, such outsized move appears to be the largest.

Moreover, it remains to be seen if this has been an anomaly.

If this has indeed been an aberration, then this implies that the coming figures should show a decline which should revert M3 and M0 back to the trend line. If not, recent breakout may establish an acceleration Philippine monetary aggregate trend line: an affirmation of the classic bubble.

Considering that both the private sector, lubricated by expansionary credit, and the domestic government, whom will undertaking $17 billion of public works spending, will be competing for the use of resources, we should expect that pressures to build on either relative input prices (wages, rents, and producers prices), particularly on resources used by capital intensive industries experiencing a boom, and or, but not necessarily price inflation.

Such dynamics would exert an upside pressure on interest rates that would eventually put marginal projects, including margin debts on financial assets operating on leverage, on financial strains which lay seeds to the upcoming bust.

Yet the idea that price inflation is a necessary outcome of an inflationary boom has been misplaced.

In the modern economy, many things such as productivity growth, e.g. informal economies and or technological innovation) or today’s financial quirks, e.g. as excess banking reserves held at the central banks, such as the US Federal Reserve, can serve to neutralize its effects.

As the great dean of Austrian school of economics Murray N. Rothard wrote[11],

Similarly, the designation of the 1920s as a period of inflationary boom may trouble those who think of inflation as a rise in prices. Prices generally remained stable and even fell slightly over the period. But we must realize that two great forces were at work on prices during the 1920s—the monetary inflation which propelled prices upward and the increase in productivity which lowered costs and prices. In a purely free-market society, increasing productivity will increase the supply of goods and lower costs and prices, spreading the fruits of a higher standard of living to all consumers. But this tendency was offset by the monetary inflation which served to stabilize prices. Such stabilization was and is a goal desired by many, but it (a) prevented the fruits of a higher standard of living from being diffused as widely as it would have been in a free market; and (b) generated the boom and depression of the business cycle. For a hallmark of the inflationary boom is that prices are higher than they would have been in a free and unhampered market. Once again, statistics cannot discover the causal process at work.

Nonetheless, while price inflation may not be the necessary and sufficient factor for upending a boom, the lack of its presence does not prevent business cycles from occurring.

Moreover, the yield chasing boom will likely spur greater demand for credit that will similarly put pressure on interest rates.

In addition, competition for resources by both the government and the private sector will likely increase demand for imports that subsequently leads to wider trade deficits. Eventually bigger trade deficits may impact the current account that could put pressure on foreign exchange reserves.

And as noted last December[12],

And since the prolonging of the domestic boom requires foreign capital or that trade deficits would need to be offset by capital accounts or increasing foreign claims on local assets, either the BSP loosens up or keeps an eye closed on foreign money flows. Most of which will likely come from hot money inflows seeking refuge from inflationism and financial repression.

By then the Philippines could be vulnerable to “sudden stops” which may arise from a domestic or regional if not from a global event risks.

And as pointed out last week, today’s global pandemic of bubbles will most likely alter the character of the next crisis.

Instead of many nations offsetting bursting bubbles of some nations, the coming crisis would translate to a domino effect.

Wherever the source or origins of the crisis, the leash effect means cascading bubble implosions over many parts of the world. The escalation of bubble busts would prompt domestic political authorities to intuitively embark on domestic bailouts and fiscal expansions (or the so-called automatic stabilizers), and for central bankers to aggressively engage in monetary easing for domestic reasons—or a genuine “currency war”.

In contrast to what seems as phony “currency wars”, real currency wars have had broad based carryover effects from expansionist political controls. This usually includes price and wage controls, capital and currency controls, social mobility and border controls, trade controls or protectionism and other financial repression measures[13] (e.g. taxes, regulations on banks, nationalizations, caps on interest rates, deposits and etc…).

How inflationism leads to forex controls and the spate of other political controls, the great Ludwig von Mises explained[14]

But the government is resolved not to tolerate any rise in foreign exchange rates (in terms of the inflated domestic currency). Relying upon its magistrates and constables, it prohibits any dealings in foreign exchange on terms different from the ordained maximum price.

As the government and its satellites see it, the rise in foreign exchange rates was caused by an unfavorable balance of payments and by the purchases of speculators. In order to remove the evil, the government resorts to measures restricting the demand for foreign exchange. Only those people should henceforth have the right to buy foreign exchange who need it for transactions of which the government approves. Commodities the importation of which is superfluous in the opinion of the government should no longer be imported. Payment of interest and principal on debts due to foreigners is prohibited. Citizens must no longer travel abroad. The government does not realize that such measures can never "improve" the balance of payments. If imports drop, exports drop concomitantly. The citizens who are prevented from buying foreign goods, from paying back foreign debts, and from traveling abroad, will not keep the amount of domestic money thus left to them in their cash holdings. They will increase their buying either of consumers' or of producers' goods and thus bring about a further tendency for domestic prices to rise. But the more prices rise, the more will exports be checked.

In short, one form of interventionism breeds other forms interventionism.

For now, the domestic yield chasing mania means an increasing pile up on winning trades.

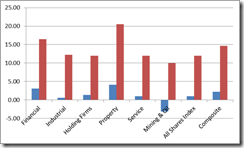

And instead of the rotation to the mining sector as has been for the past years, the latter of which has been smacked by a double black eye from the Semirara landslide and from the recent blowup in metal prices, dampened appetite for the mines has shifted the public’s attention back to the last year’s biggest winners.

The trio: property, financial and banking and property weighted holding firms has reclaimed their leadership positions.

Thus the checklist for the manic phase of stock market bubble:

Deepening price or yield chasing dynamics √

Popular themes √

This time is Different mentality √

Expansionary credit √

Every Bubble is a Thumbprint

And it’s not just me.

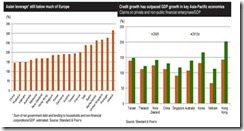

One analyst from the S&P credit rating agency recently raised his concern over Asia’s growing appetite for debt where he says many Asia-Pacific countries have raised debt “well above the levels in the mid-2000s”, importantly, credit to GDP ratios of few nations has been “high relative to peers at similar income levels”

S&P KimEng Tan at an interview with Finance Asia further adds[15],

Real estate downturns may be less of a threat to financial institutions in the key economies than they were in the worst-hit developed economies. Nevertheless, credit losses can still increase rapidly if general economic conditions weaken materially. The top concern is that China’s growth could slow sharply before the developed economies recover sufficiently to contribute to maintaining moderate growth. The slowdown is likely to have a material negative effect on economic activities across the Asia-Pacific.

Although the seemingly disinclined Mr. Tan downplays the imminence of the risks of a crisis by making apple-to-orange comparison with debt levels in Europe.

Let me improve by saying that each nation have their own unique characteristics or idiosyncrasies, therefore it may not be helpful to make comparisons with other nations or region. Moreover, while many crises may seem similar, each has their individual distinctions.

For instance, one Bloomberg article I came about highlights the portentous troubles that lie ahead for Asia. The article[16] relates on the symptoms: South Korea’s household debt “rose to a record 959.4 trillion won last quarter”, and equally such debt has “reached 164 percent of disposable income in 2011, compared with 138 percent in the U.S. at the start of the housing crisis”.

South Korea’s domestic credit provided by the banking sector[17] (shown above), as well as, domestic credit to the private sector[18] as % of has reached over 100% GDP, although slightly below the recent peak.

China’s mounting debt problem and property bubble has also been daunting. Recent easing and government intervention via stealth spending programs[19] has prompted a recovery in housing prices. According to a Bloomberg report[20] (italics mine)

Average per-square-meter prices in 100 cities tracked by SouFun are five times average monthly disposable incomes.

In addition,

Home sales in China’s 10 biggest cities almost quadrupled to 8.5 million square meters in the first five weeks from last year, property data and consulting firm China Real Estate Information Corp. said in an e-mailed statement Feb. 19.

Either China and South Korea’s productivity growth has to catch up with the lofty levels of debt or that untenable debt dynamics will eventually lead to self-destruction whether triggered by an upsurge in interest rates or by weakening of the economic conditions or from a global contagion or simply unsustainable debt.

Interventions can only delay the day of reckoning but worsen the longer term entropic impact.

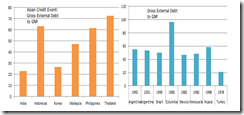

These are debt levels when “credit events” occurred via the Asian Crisis (left window) and of the other emerging market debt crisis (right window). Data from Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart as presented by Ricardo Cabral at the Voxeu.org[21]

First, there has been no definitive line in the sand for credit events. South Korea has for instance very low external debt when the crisis struck, although Argentina’s debt crises shared the same debt levels during 2 crises within 10 years.

Second, external debt may or may not function as an accurate gauge today. Many economies have resorted to amassing debts based on internal local currency units and from local currency bond markets which has been unorthodox relative to the past.

In addition, financial innovation may mean risks have spread to other potential channels as securitization and derivatives.

Nonetheless, external debts have indeed been swelling in Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia and even in South Korea with the exception of Malaysia.

The implication is that there are many potential sources of black swan events.

The Wile E Coyote Moment

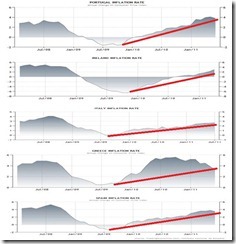

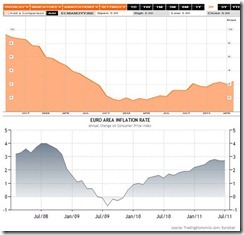

Yet the current booming environment has been prompting policymakers of several economies to pull back on current easing programs.

The Chinese government has recently withdrawn funds from the financial system. In addition, the Chinese government has recently ordered more property curbs[22]. Such perception of tightening has prompted for a 4.86% plunge in the Shanghai Index (SSEC) over the week, which reverberated throughout the commodity markets (see CRB line behind SSEC).

Prior to February, Chinese authorities were loosening up on the monetary spigot, then all of a sudden the change of sentiment. As one would note, this is an example of how markets has been held hostage to the actions of authorities.

Of course it is also important to point out that the European Central Bank (ECB) has been draining funds from the system since October of 2012 which has coincided with the peak in gold prices. February’s dramatic shrivelling to March lows of the ECB’s balance sheet has mirrored the collapse in gold prices[23].

And it’s not only the ECB.

Swiss banks have been required only this month to up their capital reserves by 1%.

And in the face of credit fueled property boom in Europe’s richer nations as Switzerland, Sweden and Norway, Sweden’s regulators have warned that they are ready to tighten more given the recognition of a brewing debt bubble. “Swedish households today are among the most indebted in Europe” the Bloomberg quotes a Swede official[24].

Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s government has doubled sales tax[25] on high end real estate worth HK$2 million and above, as well as, commercial properties in her attempt to suppress bubbles that has spread from apartments to parking spaces, shops and hotels

As one would note, wherever one looks there have been blowing bubbles: a global pandemic of bubbles

So contradicting policy directions can became a headwind and increased volatility for financial markets, including the Phisix. Although domestic dynamics are likely to dictate on momentum.

Nonetheless bubbles eventually peak out regardless of interventions.

Again in Hong Kong, prior to the sales tax hike, bankruptcy petitions has risen to 2 year highs[26]

Things operate or evolve on the margins. And so with puffing bubbles. Deflating bubbles always commences from the periphery that eventually moves into the core.

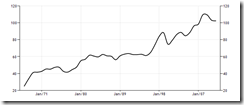

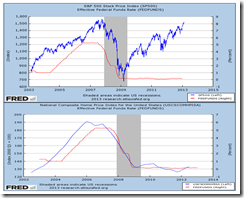

The US housing bubble cycle should serve as a noteworthy paradigm.

US home prices represented by the National Composite Home Price Index peaked (lower window blue line) at the close of 2005, as interest rates increased (red line). The Fed controlled Fed fund rate topped in 2007.

Notice that the mild descent of home prices in 2006 steepened or accelerated in 2007. The housing bear market fell into a trough only in 2011 and began showing signs of recovery in 2012.

Yet the US stock market (S&P 500 blue line top window) continued to ignore the developments in the housing markets in 2006-2007, as well as, the interest rate hikes. In fact, gains of the S&P seem to have accelerated when interest rates peaked.

The stock market came to realize only of the flawed perception of reality when home prices affected the core, or when the banking and financial system began to implode. It was like cartoon character wile e coyote running off a cliff.

From hindsight, the divergence between housing and the stock market, the massive debt buildup on the housing, mortgage, banking and financial sectors, the denial by authorities of the existing problem, the transition of deflating bubbles from the periphery to the core and the public’s persistent yield or momentum chasing dynamics, all meets the criteria of a manic phase in motion.

But as I said last week, the next crisis may not be similar to the US housing crisis of 2008.

Then policymakers have been mostly reactive, today policymakers are pro-active, pre-emptive and considered as activists. The outcome isn’t likely to be the same.

Importantly, given that almost every nations have been serially blowing bubbles, a domino effect from a bubble bust would either mean the path to genuine reform (bankruptcies and liberalization) or more of the same troubles but in different templates (stagflation, protectionism, controls of varying strains and etc…). I am leaning onto the latter outcome, although I am hoping for the former.

Everything now depends on the Ping Pong feedback loop between markets and international policymakers.

Although from the lessons of US bubble, I believe that the Phisix in spite of several increases in interest rates may go higher.

Momentum will initially mask the traps that have been set, until of course, economic reality prevails; eventually. Or going back to wile e coyote analogy, wile e coyote will continue to chase after Road Runner to the cliff until he realizes that there is no more ground underneath.

Again bubbles signify a market process.