One of the myths perpetuated by those who can’t explain the behavior of markets is to resort to the “emotions” fallacy.

A good example as I pointed out is this comment[1]

Hong Kong financial official K.C. Chan urged investors to “stay calm” and not be “spooked by the market”

These people are mistaking effects as the cause. Markets don’t spook people. That’s because markets are essentially people and market price signals represents the collective actions of people. People react to markets out of certain stimulus or incentive. People don’t get euphoric or frightened for no reason.

A good example can be seen below

A fight or flight response by our brain is always result of a stimulus or incentive to act or react.

As I earlier wrote[2],

When uncertainties or the prospect of peril emerges, our brain’s amygdala responds by impelling us either to fight or to take flight. That’s because our brain has been hardwired from our ancestor’s desire for survival—they didn’t want to be the next meal for predators in the wild.

Applied to the present state of the markets, the legacy of our ancestor’s base instincts still remains with us.

So when people’s collective action results to a stock market crash, that’s because there has been an underlying uncertainty or imbalance which these participants see as having “baneful” impact to their portfolio holdings. Such stimulus or incentives triggers the amydgala’s fight or flight response even on the marketplace.

Hence if crashing markets are seen as an ephemeral episode unsupported by fundamentals then many buyers are likely to step in and put a floor to the prices. People who say that markets have been “irrational” or “emotional” are only appealing to their interventionist intuitions.

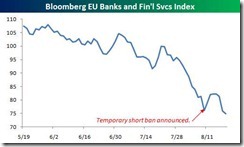

Yet if crashing markets are seen as fundamentally driven, then the crash dynamic will continue. Interventions such as the recent ban on short sales will fail[3] which 4 European nations recently applied to bank and financial issues[4].

Differentiating Short and Long Term

In addition, one cannot coherently argue that the long term outcome of markets is rational while short term outcomes are emotive (or irrational). To apply this to Warren Buffets’ celebrated commentary,

In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run it is a weighing machine.

Every action by individuals contains elements of emotion. That’s because our actions are always designed to replace the current state of uneasiness. Content or discontent signify as emotional states. Emotions are simply part of individual actions. Thus seen in a collective sense, markets are always ‘emotional’ even during ‘normal’ days. Perhaps it is only in the degree where the nuances can be made.

To add, since the long run represents the cumulative effects of short run actions, there has to be a smoothing out effect for the long run actions to dominate.

Applied to Mr. Buffetts’ axiom, for the weighing machine effect to prevail over the long run, the series of short term ‘weighing machine’ dynamics has to dominate the series of short term ‘voting machine’ actions. Or the probability of distribution has to skew towards forces of the weighing machine dynamic otherwise the voting machine effect will takeover.

Boom Bust Cycles Have Real Effects

The state of the US markets appears to be revealing on such symptoms, a nice illustration can be seen in the chart below.

US markets have become nearly an “all or nothing” pattern, where market breadth reveals that stock prices in general either floats or sinks in near simultaneously during volatile days.

As Bespoke writes[5], (bold emphasis mine)

Whenever the market has a day where the net advance/decline (A/D) reading of the S&P 500 is greater than 400 or less then negative 400, we call it an 'all or nothing' day. During the credit crisis, all or nothing days were incredibly common. In 2008, we saw a peak of 52 all or nothing days, which works out to an average of about one per week. Since then, we have seen a decrease in the number of all or nothing days, but they still remain elevated.

So far this year there have been 27 all or nothing days, which works out to a still elevated annualized rate of 43. At this time just last month, there had only been 17 all or nothing days this year, which at an annualized rate of 31 would have been the lowest level since 2007. Back then, many investors were hoping that the market was finally returning to pre-crisis levels of normalcy.

As one would note from the above, current markets have hardly been about earnings, as cluster based movements represent as the NEW normal where markets have been latched to political actions more than from market forces as dogmatically embraced by mainstream.

In short, this exhibits more evidence of the increasing dependency of the S&P 500 to political interventions as a major force in influencing equity prices.

As the great Murray N. Rothbard wrote[6],

In the purely free and unhampered market, there will be no cluster of errors, since trained entrepreneurs will not all make errors at the same time. The "boom-bust" cycle is generated by monetary intervention in the market, specifically bank credit expansion to business.

Remember, boom bust policies impacts not only the financial markets but has real impact to the economy. Through the manipulation of interest rates, patterns of consumption and savings and investment, wages, relative price levels at every stages of production, capital structure, earnings, and etc., are directed away from consumers preferences and rechanneled into stages of capital goods sector where politically directed actions would now signify as distortion of prices, miscoordination of resources or as malinvestments which eventually would have to be liquidated.

Again Mr Rothbard,

If this were the effect of a genuine fall in time preferences and an increase in saving, all would be well and good, and the new lengthened structure of production could be indefinitely sustained. But this shift is the product of bank credit expansion. Soon the new money percolates downward from the business borrowers to the factors of production: in wages, rents, interest. Now, unless time preferences have changed, and there is no reason to think that they have, people will rush to spend the higher incomes in the old consumption-investment proportions. In short, people will rush to reestablish the old proportions, and demand will shift back from the higher to the lower orders. Capital goods industries will find that their investments have been in error: that what they thought profitable really fails for lack of demand by their entrepreneurial customers. Higher orders of production have turned out to be wasteful, and the malinvestment must be liquidated.

Today’s market environment has accounted for as the continuing saga of the 2008 liquidation phase which has been constantly delayed, deferred and partly absorbed by government through sundry interventions and systemic inflationism designed to save the fragile, broken and unsustainable system.

And the effects of the gamut of political interventionism has been manifesting into the actions of equity markets.

Everybody can wish for the old days, but prudent investors would need to face up with reality or take the consequences of ideological folly.

[1] See Japan's Minister Calls for More Inflationism to Stem Global Market Crash, August 19, 2011

[2] See Managing Risk and Uncertainty With Emotional Intelligence, March 20, 2011

[3] Bespoke Invest, A Rough Week For European Banks, August 19, 2011

[4] See War against Short Selling: France, Spain, Italy, Belgium Ban Short Sales August 12, 2011

[5] Bespoke Invest, 'All or Nothing' Days on the Rise, August 16, 2011

[6] Rothbard, Murray N. The Positive Theory of the Cycle, Chapter 1 America’s Great Depression

No comments:

Post a Comment