Malaysia’s inflation data rose faster than consensus expectations.

Fast-rising prices in Malaysia, as the government dials back subsidies and the economy grows at a strong clip, could prompt the central bank to raise interest rates that have been on hold since mid-2011.Data out Wednesday showed consumer prices rose 3.4% in January from a year earlier, the fifth straight month of gains and fastest pace in two and a half years. That was up from 3.2% in December and a tad above the 3.3% median forecast in a Wall Street Journal poll.

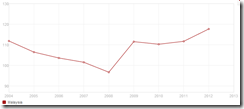

Malaysia’s price inflation seems a tad away from the 2011 highs.

In previous accounts where price inflation spiked beyond 5% levels, such has been associated with major economic turbulence, as the Asian Crisis and the the global crisis triggered by 2007-2008 US housing bust which culminated with the Lehman bankruptcy.

While 3.4% seems far from the 5% threshold, current dynamics seems to point at inflation rates headed towards such direction, unless otherwise reversed.

Media blames inflation on supply side quirks. From the same article.

Economists say inflation will remain elevated for the rest of the year after electricity tariffs were raised in January. That follows other moves last autumn to raise prices of two widely-used fuel variants and to scrap subsidies on sugar.

Lifting of subsidies have hardly been the real forces driving Malaysia’s price inflation.

Instead the major forces driving Malaysia’s inflation has been a credit boom that has fueled a property bubble as previously discussed.

Since 2001, loans to the private sector has zoomed with the kernel of the accelerated credit boom happening from 2008 onwards. Loans to the private sector has ballooned by about 2.6x from December 2013 compared with the 2001 levels

Seen from another view, loans provided by the banks as % gdp, which dropped to a recent low of 109.4% in 2007 has regained a second wind to swell to a record 134% in 2012, based on World Bank data.

Banking loans includes “all credit to various sectors on a gross basis, with the exception of credit to the central government, which is net”

Also domestic credit provided to the private sector in the category of “loans, purchases of nonequity securities, and trade credits and other accounts receivable, that establish a claim for repayment” has increased from a recent low of 96.7% in 2008 to a record 117.8% in 2012 again from the World Bank data

Three facets of credit data depict on the same picture.

Yet all these fractional reserve based money creation has led to soaring money supply.

Malaysia’s M3 has accelerated along with the ramping up of credit over the same period.

Seen in terms of % growth, Malaysia’s M2 spiked to 14.6% in 2011 before retracing back to the 7-8% levels in 2013.

Malaysia’s average annualized growth has been at 4.65% from 2000-2013 according to tradingeconomics. This means that M2 has been running about more than double the growth of the economy

And interestingly, Malaysia’s banking credit profile looks almost exactly like the Philippines in terms of supply side distribution. The gist of credit growth has been in finance, real estate and trade! This is according to a report from RHB.

The difference is that Malaysia’s household has also been massively acquiring credit. And that’s the reason why private sector credit or banking sector loans have been above the 100% level in terms of gdp.

This also means Malaysians have more financial depth than the Philippines for them to partly offset the adverse effects from credit inflation via productivity growth.

Unfortunately, artificial booms will eventually come to an end.

Behind the scenes, Malaysia’s credit boom has been driven by zero bound official rates. Or if measured from 10 year Malaysia’s local currency denominated treasuries, yields have been in a decline since 2009 as credit soared.

However, this picture seems to have been reversed as yields have been on an upside streak in late 2013 to reach 2009 levels. This means that the easy money environment that has stoked the boom has come under pressure from the bond vigilantes

Even the Malaysian currency, the ringgit, has been showing signs of pressure. Since Abenomics-Bernanke taper in May-June2013, the ringgit has been in a major downtrend interspersed with short term rallies.

And such bond market-currency weakness should come as a surprise to the mainstream because Malaysia’s external façade looks solid; current and trade accounts remain in surpluses, government external debt has been in decline and Malaysia has $140.4 billion of forex currency reserves as of December.

Malaysia’s forex reserves peaked in August 2011 at $155 billion, but perhaps, due to the latest EM turmoil, the Malaysian central bank may have used her surpluses to counter foreign outflows.

The bond-currency weakness hasn’t been shared yet by the other markets...yet

Malaysia’s default risk as measured by the 5 year CDS spiked in August 2013, fell back to October lows and surged again in January (but only halfway) from the August highs. Recently the 5 year CDS has returned to October lows

Interestingly Malaysian stocks, as measured by the KLSE, which has also been hammered in June 2013, bounced backed strongly to even carve new highs at the close of 2013.

This seems as signs of the growing desperation by those addicted to easy money climate to resist the ongoing shift in the economy by forcibly bidding up stocks in the hope of a return of the boom days.

Yet the divergence in signals means that eventually something will have to give. Will bond yields reverse that should power stocks higher and bring about the next wave of credit boom? Or will stocks adjust to reflect on rising rates?

All these will depend on how rates will ultimately affect debt.

Let me post again ASEAN’s debt chart from the World Bank.

Malaysia’s overall debt runs at about 200% of gdp, mostly due to household debt. Malaysia’s economy in 2012 has been at a nominal US $307.2 billion. This makes her credit exposure which has been largely dependent on low rates at about $600 billion. Again forex reserves are only 23% of Malaysia's total debt stock.

This brings us back to the earlier article who rightly points to the danger of rising inflation amidst growing debts.

Caught in the middle are Malaysia’s consumers, who are facing growing debts just as rising prices erode their disposable income. Consumer borrowing in Malaysia has risen some 12% a year for the past five years, with household debt climbing to 80.5% of GDP by the end of 2012 from 50.4% in 2008, one of the highest levels in Southeast Asia.The debt and inflation dynamic surely contributed to December’s weak consumer confidence reading, the lowest since June 2009.

Missing in the article is how inflation would mean higher rates and how higher rates would impact the cost of debt servicing in the face of slowing demand that subsequently should raise credit quality issues. Or differently put, how will highly indebted Malaysians be able to pay back the debt which servicing costs has been rising, if growth slows aggravated by higher inflation? Will these not increase Malaysia's credit risks?

At the end of the day, like the Philippines Malaysia appears now confronted with a stagflationary setting (even unemployment rates have increased in November 2013 which broke out of 3.3% resistance levels), whose rising rates threaten to serve as a pin that could prick on Malaysia’s credit bubbles.

No comments:

Post a Comment