As compared with liberal democracy, a system of social democracy offers greater political profit for policy measures that promote poverty and dependence. A system of social democracy creates two sets of people who have interests that support the maintenance of poverty and dependence to a greater extent than would be true under liberal democracy. One set is the recipients of state-supported services, who are content with the terms of the trade by which they replace independence with state support and who might offer their voting support in return. The other set is the providers of those services, for whom the continuation of poverty and dependence is a source of income--Richard Wagner

In a trifecta of credit rating upgrades, the Moodys rationalizes last week’s upgrade of the Philippines as “The Philippines’ economic performance has entered a structural shift to higher growth, accompanied by low inflation”[1]

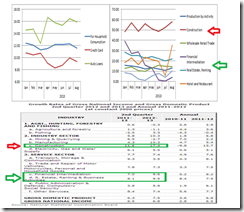

Figure 1: Credit and Statistical growth

Speaking of “structural shift”, behind whatever statistical growth extolled by Moodys lurks the perils which has been overlooked and dismissed by the mainstream, including the big 3 credit rating agencies…a credit bubble.

As I have repeatedly been pointing out, the supposed “structural shift” in the economic growth dynamics represents an escalation of imbalances between supply and demand financed by a credit boom.

The domestic central bank, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) recently released the August data of the banking system’s credit growth[2]. The August figures reveals that the financial market meltdown during the last week of the said month has largely been discounted and that credit growth appears to be reaccelerating upwards, specifically in what I call as the bubble sectors: property, construction, trade (shopping mall bubble) and hotel and restaurant (casino bubble).

Credit growth on a year to year basis in the construction sector zoomed to its highest level for the year at an incredible 58.03%. Credit growth in the hotel and restaurant sector spiked to 35.11%, wholesale and retail trade was steady at 14.32% while real estate, renting and business services, as well as, financial intermediation bounced from the July lows to grow by 21.89% and 4.09% respectively over the same period as shown in the top right window of Figure 1.

Credit from these industries account for 49.17% of total banking economic production loans.

Credit growth in the manufacturing sector, which I don’t see as in a bubble, expanded 10.1% also the highest level for the year but the rate of growth has oscillated between 1-10%, or for an average growth rate of 5.845%.

This is unlike the growth rate in the bubble sectors where, with the recent exception of financial intermediation, has grown steadily beyond the growth rate of the demand side.

Consumer credit growth has only grown 11.52% in August largely led by car sales which inflated by 15.9% (y-o-y).

Remember only about 21% of the Philippine households has access to the formal banking system. This means that unless the banking penetration level magically multiplies exponentially or that the informal economy massively booms, demand side growth will be inadequate to keep pace with the supply side. And this also means that big players who constitute the supply side and who has access to credit markets (banking and bond markets) have far greater sway on statistical growth figures than the consuming public[3].

This is why the mainstream like the New York Times article on Moodys upgrade on the Philippines has, like the rest of ivory tower based experts, been lost in understanding or explaining the Philippine political economy “Surging growth has yet to translate to wealth for the country’s millions of poor”. Zero bound rates represent a transfer of resources or subsidy to the wealthy via asset bubbles. Yet interpreting statistics as economic analysis is mistaking the forest for the trees.

As a side note: A massive boom in the informal economy signifies impossibility. The informal sector exists in response, or as avoidance to the burdens of regulations and taxes. If the informal booms then they will obviously lose their cloak of invisibility from political authorities. The curse of informal economy is that their growth will be limited vertically or on the upside but whose scalability in growth will be horizontal (there can be more informal players as taxes and regulations increase)[4].

Figure 2 Demand side Growth

And this flagrant imbalance can be seen from the perspective of household final consumption expenditure[5] (HFCE), see figure 2, which in the second quarter only expanded by 5.2% (in constant prices) relative to the supply side growth say construction 17.4%, real estate, renting and business services 9.5%, financial intermediation 9.5% and trade 7.3% (at constant prices) see bottom window of Figure 1.

Another note: The credit growth figures I cited are of August, while NSCB’s data are as of the 2nd quarter’s, but it is important to point out that August figures are most likely to translate to spending activities for the month or for September. This means that if the August credit trends will be maintained and reflected on September data then statistical growth will remain at the consensus expectations. But the longer the artificial boom is, the greater the imbalances, the bigger the destabilizing adjustments.

Such relative oversupply particularly on the bubble sectors are symptoms of an outrageous misallocation of resources, the Php 64 billion question is how will such ‘structural’ imbalances be resolved?

The Philippine government has been lucky that remittances (both informal and formal) and foreign currencies revenues from BPOs has masked the adverse effects from its bubble blowing policies for now.

Yet how are blowing bubbles which Moody’s sees as “structural shift to higher growth” sustainable?

Credit Rating Upgrades: Those whom the gods wish to destroy they first make mad

Latin writer Publilius Syrus once wrote[6] “Whom Fortune wishes to destroy she first makes mad”. This is a variant of a popular quote “those whom the gods wish to destroy they first make mad” misattributed to a Greek playwright Euripides[7]

The Bible warns how this takes place:

Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall. (Proverbs 16:18)[8]

Yet even the Bible warns about the hazards of overconfidence as expressed by pride via the “This time is different” outlook

While credit rating upgrades has reinforced on the optimism bias by the mainstream, little is appreciated how ‘blessings’ from credit rating agencies signify as ‘kiss of death’ for the supposed beneficiaries.

Hasn’t it not just been in January of 2012, when Moody’s joined the bandwagon of upgrades on India and Indonesia?

Indonesia in January 2012 “regained its investment grade ratings in 14 years” says the Bloomberg[9].’

I have pointed out earlier how Indonesia seemed like a ASEAN’s Canary in the Coal Mine[10]

Also in January of 2012, India's rating for short-term foreign currency bank deposits has also been upgraded from speculative to investment grade by Moody’s according to India’s Economic Times[11]

Have not the same countries been the focal point of the recent selloffs?

Warren Buffett and many major investors have already cut their losses in India. Some fear of the heightened risks of an Indian sovereign debt crisis[12].

India has already an inverted yield curve which usually precedes a recession or a crisis.

And even as India’s financial markets has stunningly recovered from the recent bout of volatility (yes India’s equity benchmark even broke to new highs recently) in the real economy, “Restructured loans” according to a recent report from Bloomberg[13] “are defaulting at a record rate at Indian banks”

The markets appear to be buying into absurdity that the FED un-taper will serve as antidote to India’s real economic problems. Beats me, but an inverted yield curve and record defaults on the banking system are hardly signs of optimism. They are in contrary ingredients for a market shock and or a crisis.

Meanwhile S&P raised Indonesia’s credit rating in April of 2011 to the highest level since the Asian Crisis in 1997 due to supposedly a “resilient economy” and “improving finances”[14]. In two years or in May of 2013, the S&P apparently changed their minds and downgraded Indonesia to stable from positive[15]. So what happened to resilient economy and improving finances?

After the Indonesian downgrade, this September, the S&P warned that India’s has greater chances of a downgrade than Indonesia[16]. Whatever happened to their earlier accolades? Fun times is over? Why?

Curiously the S&P warns that an Asian banking crisis shouldn’t be ruled out if China’s credit bubble implodes which poses as a “threat to the region’s financial stability”[17]

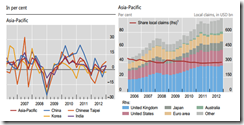

Figure 3: Foreign banking claims on Asian Borrowers

I guess from the Moody’s actions on the Philippines, the US credit rating agency may have come to believe in the tooth fairy of “decoupling” which is in contravention to today’s highly globalized economy

Yet evidence proves otherwise. Cross-border credit to borrowers in Asia Pacific or intra-regional borrowings as shown via its growth rates in Figure 3 left window, remain a significant dynamic in the Asia and the global banking system. The same holds true for credit provided by foreign banks’ offices located in Asia Pacific which stood at end 2012 at $2.4 trillion[18] (right window)

This implies that should a China meltdown occur as the S&P fears, dismissing the risks of a contagion would signify a ridiculous and reckless assumption. The trade, banking-financial and labor channels are all potential transmission mechanisms for a contamination.

ASEAN’s June and August financial market meltdown has already provided clues that contagion risks are for real and represents a clear and present danger despite the proclamations of ivory tower experts.

Yet it’s not just Moody’s though. Despite a horrible track record of predictions, late September, the IMF declared of the Philippine as immune to a FED tapering[19].

Lately, the Asian Development Bank joined the ranks of the “all hail the Philippine economy”, where they claim that the Philippine economy is “expected to continue to perform strongly”[20] relative to weaker neighbors.

“Strongly” really depends on the actions of the global bond vigilantes.

Interestingly here is ADB’s 2007 outlook for the US and Asia in 2008[21] (bold mine)

If growth in the United States (US) lurches down, developing Asia would not be immune. But the tremors from a downturn in the US are likely to be modest and short-lived even if it falls into recession. Available evidence suggests that, depending on timing, severity, and duration, a US recession could clip growth in developing Asia by 1–2 percentage points. If a synchronous steep downturn in the US, euro zone, and Japan were to occur—an event that currently seems improbable— growth in developing Asia would be at greater risk. But stout reserves, improved financial systems, and scope for policy adjustments put the region in a better position to weather any storm.

Interesting because the ADB correctly assessed of the contagion, but briskly veered away from embracing such position and opted to dismiss such risks as “seems improbable” by raising the same pretext which the mainstream has been using today “stout reserves, improved financial systems, and scope for policy adjustments put the region in a better position to weather any storm”

We know that from the hindsight, contra ADB’s rationalization, the “Great Recession spread to Asia rapidly and has affected much of the region” to quote the Wikipedia[22].

Then, maybe the ADB just talked on the interests of their fund providers or the “members' contributions” where the US and Japan represent as the biggest voting members of the ADB[23] with 12.78% weight each. In short despite the recognition of risks, the ADB worked as a spinmeister for their clients.

Going back to what seems as the curse of the credit rating agencies; credit rating agencies have almost always been the last to know or has functioned reactive agents to an unfolding event. They hardly saw risks.

Writing at the Project Syndicate New York University Professor Roman Frydman and University of New Hampshire Professor Michael D. Goldberg asked why credit agencies tend to underappreciate risks[24]

Until six days before Lehman Brothers collapsed five years ago, the ratings agency Standard & Poor’s maintained the firm’s investment-grade rating of “A.” Moody’s waited even longer, downgrading Lehman one business day before it collapsed. How could reputable ratings agencies – and investment banks – misjudge things so badly?

In the last crisis such late reaction by the big 3 seems understandable.

That’s because these agencies played a big role in the inflation of the mortgage-securitization bubble. They functioned as the stamp pad for issuers of slicing dicing and mixing of toxic securities to sell into a market restricted by law to hold the safest AAA securities.

These credit rating agencies were responsible for giving the highest ratings to “over three trillion dollars of loans to homebuyers with bad credit and undocumented incomes through 2007. Hundreds of billions dollars worth of these triple-A securities were downgraded to "junk" status by 2010, and the writedowns and losses came to over half a trillion dollars. This led "to the collapse or disappearance" in 2008-9 of three major investment banks (Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and Merrill Lynch), and the federal governments buying of $700 billion of bad debt from distressed financial institutions”, notes the Wikipedia.org[25]

The 3 biggest credit rating agencies were essentially in rabid denial of their mistakes as manifested in the collapse of the institutions that bought into their deception.

The last to know reactions by credit rating agencies had equally been apparent during the boom bust cycle that led to the Great Depression in the 1930s

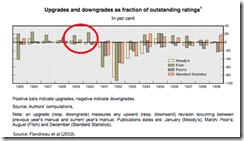

Figure 4: Credit ratings changes during the Great Depression

As one would note from figure 4, credit rating upgrades dominated in 1929-1930 even when the October 29, 1929 Black Tuesday crash in Wall Street signalled the advent of the Great Depression[26]

In a paper presented to the seminar sponsored by the Bank of International Settlements last January, University of Geneva’s Professor Marc Flandreau enunciates the role of the credit rating agencies[27] (bold mine)

An interesting difference is between the reaction of credit agencies and Crédit Lyonnais. In the middle of the Russian confidence crisis, Crédit Lyonnais told investors, “Oh, Russia is really safe. What we told you was correct”. And they kept lending to Russia, and things were sorted out for a while at least. On the eve of WWI the Russian economy was booming again and it took the First World War and a few other things occurring a number of years later for default to eventually come. But in the case of the interwar crisis, rating agencies just ran away. When trouble started, they began downgrading massively. In the case of Moody’s, for instance, in one week, after the sterling crisis in September 1931, 80% of the sovereigns it rated were being downgraded. When you look at the profile of sovereign upgrades and downgrades by Moody’s, you have a line that is very similar to what we have seen in the most recent crisis. Suddenly, beliefs are updated and it often means massive downgrades. It’s not who you are, it’s who makes your reputation.

In and of itself, the big 3 credit rating agencies have not been entirely a jinx. Like momentum or yield chasers, these credit rating agencies tend to piggyback on a blossoming fad whether to the upside or to the downside.

On the upside, they frequently misinterpret inflationary booms as positive structural economic changes. They hardly foresee the risks involved and their upgrades compound on the manic “this time is different” outlook.

And the frequency of vacillation of credit rating changes only underscores how an army of experts dependent on econometric models usually misreads real economic developments.

It has been a different story for 2007-2008 crisis. These agencies played a critical principal-agent conflict-of-interest role in the parlaying toxic “structured finance” securities to the public as they had been paid by the issuers which meant that determination of credit ratings worked in the interest of the issuers.

The curse from the credit rating upgrades has mostly been in the political arena. Credit rating upgrades emits a wrong impression on policymakers. Policymakers interpret upgrades as licenses to engage in irresponsible borrowing and spending policies. Upgrades also extrapolate as rewards for policymakers to maintain bubble policies.

Since credit ratings influence social policies, credit ratings are susceptible to politicization. The countersuit between the US government, which charged the S&P of supposed ignoring of the company’s own standards during[28], and the S&P which countercharged that the US lawsuit signified as an harassment or retaliation for the S&P’s downgrade of the US government in August of 2011[29] is an example.

So could the trifecta of credit rating upgrades have been a reward for the government’s plan to allow US bases in the Philippines[30]?

At the end of the day, credit rating upgrades seem like whom the credit rating gods wish to destroy they first make mad

SMC and the Confidence Game

The big 3 credit rating agencies have failed to account for the evolving business models underpinning the “structural shift into higher growth” via increased leveraging.

The following doesn’t serve as recommendations. Instead the following has been intended to demonstrate the shifting nature of business models by major firms particularly from organic (retained earnings-low debt) growth to aggressive leveraging or the increasing use of leverage to amplify or squeeze ‘earnings’ or returns, the deepening absorption of increased risks in the assumption of the perpetuity of zero bound rates, and how accrued yield chasing by the industry induced by zero bound rates has pushed up property prices

Two weeks back I brought to the surface the issue of what seems as the increasing use of what economist Hyman Minsky coined as the “Ponzi financing” or the increasing dependence on the use of debt and/or asset sales in order to finance existing principal and interest liabilities which funds from operations have been inadequate to service[31]. I call this debt based Ponzi-financing as Debt IN, Debt OUT

I pointed to San Miguel Corporation [PSE: SMC] as my initial example of a company undergoing such change, which not only increases the company’s risk profile but as well as systemic financial risks, which authorities irresponsibly ignores.

Last week, SMC reportedly a struck deal with the Gokongwei-led JG Summit where the latter will buy the remaining 27.1% equity of the former’s holdings in legislated monopoly electric distribution franchise Meralco[32] [PSE: MER].

Combined with SMC’s sale of 5.7% Meralco shares last July, which reportedly raised Php 17.4 billion, SMC’s exit on Meralco extrapolates to about Php 100+ billion of proceeds. If SMC decides to use this to pay what they disclosed as Php 424 billion worth of debt, then this means SMC will still have an enormous debt burden of Php 324 billion.

With the Meralco sale, SMC has yet a long way to go to bring her business back to the conservative fold.

Since the company’s free cash flows remain a speck or fraction of the huge debt burden, this means that SMC will need to hastily sell more assets and or increase free cash flows to mitigate her risk profile. Otherwise continued dependence on the debt markets mean that SMC’s liabilities will continue to balloon overtime which again would only magnify on her vulnerabilities.

Yet like all forms of Ponzi schemes, Ponzi financing is unsustainable.

Some suggested that SMC’s quandaries represent a ‘liquidity’ problem. Perhaps. The liquidity-solvency dilemma really depends on how much of SMC’s assets have been attached as collateral to existing debt, and importantly the ‘valuation’ of assets in times when the distress occurs.

In other words, we will never know of SMC’s real conditions until the realization of the tail event. But relying on current financial figures from today’s boom to generalize of a liquidity problem rather than a solvency problem would signify as severe underestimation of risks while simultaneously overestimation of rosiness from statistical figures.

In this regards we can say that despite losing 99% of his $30+ billion in just over ONE year, the former Brazilian billionaire Eike Batista, chairman of conglomerate EBX group who was ranked by Forbes as seventh wealthiest man in early 2012, is still liquid since he still has $200 million left[33]. Except that there are still claims to his remaining $200 million.

Mr. Batista lost his fortune due to a combination of factors: crash in the precious metals industry, botched oil exploration project and huge debt[34]

But to Mr. Batista’s OGX Petroleo & Gas Participacoes SA bond holders (who are left with 5.3 to 15 cents to a US dollar[35]) and to shareholders of Batista’s 3 listed companies[36], OGX, LLX and MMX, and perhaps even to the laid off employees and unpaid suppliers of Mr. Batista’s companies, the Batista case surely hasn’t been a liquidity one, regardless of the technicalities, because losses endured by counterparties have been for real.

Yet even solvent firms can also be brought down by illiquidity as in the case of United Kingdom’s Northern Rock during the 2007-8 crisis.

Northern Rock was reportedly “solvent” but had been impaired by her overreliance on money market funds. When the money markets froze, Northern Rock was compelled to approach the Bank of England (BoE) for liquidity support. Learning of this, depositors went into a panic. Northern Rock experienced a bank run or as Wikipedia.org explains, the first bank in 150 years to suffer a bank run after having had to approach the Bank of England[37]

However, the Bank of England mismanaged their role as lender of last support which led to the bank’s collapse, Cato’s Steve Hanke argues[38],

In a flash, Northern Rock went from being solvent (if temporarily illiquid) to bust. Indeed, it was government failure – the BoE’s bungled attempt to provide emergency liquidity – that transformed the Northern Rock affair from a minor, temporary liquidity problem to a major solvency crisis.

In a world of fractional reserve central banking system which promotes debt based spending as a primary tool of growth, the confidence game serves as THE critical component in the delineation between illiquidity and insolvency.

As Harvard economist Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff rightly explains of the vacillation of the confidence game[39], (bold mine)

Economic theory tells us that it is precisely the fickle nature of confidence, including its dependence on the public’s expectation of future events, that makes it so difficult to predict the timing of debt crises. High debt levels lead, in many mathematical economics models, to “multiple equilibria” in which the debt level might be sustained –or might not be. Economists do not have a terribly good idea of what kinds of events shift confidence and of how to concretely assess confidence vulnerability. What one does see, again and again, in the history of financial crises is that when an accident is waiting to happen, it eventually does. When countries become too deeply indebted, they are headed for trouble. When debt-fueled asset price explosions seem too good to be true, they probably are. But the exact timing can be very difficult to guess, and a crisis that seems imminent can sometimes take years to ignite. Such was certainly the case of the United States in the late 2000s. As we show in chapter 1, all the red lights were blinking in the run-up to the crisis. But until the “accident,” many financial leaders in the United States-and indeed, many academics-were still arguing that “this time is different.”

SM Investment’s Shift to Debt In, Debt Out?

Any entity that relies heavily on debt for finance will subject to the whims of the confidence game.

The same condition holds true for the flagship company, SM Investments [PSE: SM], of the richest family of the Philippines, Mr. Henry Sy & Family who at $12 billion worth (2012) has been also ranked 68th in the world according to Forbes[40].

At the Philippine Stock Exchange[41] [PSE: PSE] SM covers five core businesses through its subsidiaries, namely: shopping mall development and management (SM Prime Holdings, Inc.), retail (SM Department Stores, SM Supermarket, SM Hypermarket and SaveMore Stores); financial services (BDO Unibank Inc. and China Banking Corporation) and real estate development and tourism (SM Land, Inc., SM Development Corporation, Costa Del Hamilo, Inc. Highlands Prime, Inc. and Belle Corporation) and hotels and conventions (SM Hotels, SMX Convention Specialists, Hotel Specialists - Tagaytay, Cebu and Pico).

SM currently ranks second biggest market capitalization in the main 30 company benchmark of the PSE, the Phisix, with Php 650.324 billion as of Friday’s close. Two of SM’s subsidiaries BDO Unibank [PSE: BDO] and SM Prime Holdings [PSE: SMPH] have also been part of the Phisix and has free float capitalization weighting of 4.55% and 3.26% respectively (as of Friday)

Again this is a reminder that this analysis serves not as recommendations but to demonstrate of the evolving character of business models brought about by zero bound rates.

For me, the best place to spot signs of troubles has been in the cash flow department.

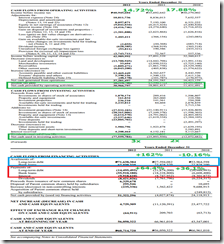

Figure 5: SM 2nd Quarter Cash Flow Statement

In the first semester of this year[42], SM Investments spent Php 7.4 billion for project expansions. Free cash flows from SM’s operations netted only Php 2.9 billion pesos. However, SM paid for Php 71 billion on debt servicing (Php 30.942 billion long term, Php 34.28 billion on bank loans, and Php 5.844 on interest payments). The lack of free cash prompted SM to resort to borrowing long term Php 88.353 billion pesos (Php 35.341 billion long term debt and Php 39.3 in bank loans).

For the same period in 2012, SM Investments undertook a massive expansion, spending Php 50.299 billion, posted negative free cash flow from operations of Php 13.865 billion. SM also paid for Php 30 billion in debt servicing. With hardly any cash flowing in SM raised debt Php 88.354 billion to finance these liabilities.

While income before taxes grew 18.67% from 2013 to 2012, growth in interest payments (16.15%) and depreciation (21%) chipped away at income before working capital changes which only grew by 7.5%.

Nonetheless free cash from operations has been eclipsed by a 32% jump in debt payments even as availments of new debts fell by 14.8%.

From the first semester’s free cash activities, cash short SM seems to have taken SMC’s path of Debt IN, Debt OUT but at a more modest scale.

Figure 6: SM 2012 Annual Cash Flow Statement

From the 2012 annual report[43], SM’s income before taxes grew 14.72% in 2012 and 17.88% in 2011. However, SM’s has been aggressively investing having seen a doubling and a tripling of investment spending in 2011 and 2012.

While the first semester free cash flow in the June 2013 report showed a negative Php 13.865 billion, the 2012 statement says that free cash flow ballooned to Php 30.967 billion.

Nonetheless the free cash flow has been inadequate to service debt which added up to Php 80.324 billion in 2012. So SM borrowed Php 133.678 billion in 2012 to cover for the deficits.

Availment of new debt spiked by 162% in 2012 coming from a decline of 10.16% in 2011, whereas debt servicing bulged by 64.4% in 2012 nearly double the growth of 36.1% in 2010.

However free cash as % of debt service has been at 38.55% in 2012, 38.5% in 2011 and 31.84% in 2010.

Figure 7 SM Long Term Debt

SM long term debt picture reveals that floating rates account for 21.6% of the Php 169.376 billion liabilities. US dollar denominated loans constitutes a bigger segment or 57.06% of the total.

While SM seems hardly in the same boat as San Miguel yet, the trend so far has been to extract earnings growth or returns from aggressive debt financed expansion. Such massive expansion reveals how SM anticipates a prolonged period of zero bound rates and an extended economic boom, by taking on more leverage and at the same time increasing interest rate, currency and credit risks. So far under present booming conditions, SM’s cash flows have been significant enough to pay for the leverage.

SM may become vulnerable to her debt exposure from a business or economic slowdown or when the interest rate environment alters or when there will be substantial fluctuations in the peso (although SM declares that it uses derivatives long-term currency swaps, foreign currency call options, interest rate swaps, foreign currency range options and non-deliverable forwards to hedge the risks).

With regards to asset valuation, SM also discloses[44] that “The valuation of investment properties was based on market values using income approach for income-generating properties and cost approach or market data approach for nonincome-generating properties, depending on whether there is an active market for these properties. The fair value represents the amount at which the assets can be exchanged between a knowledgeable, willing seller and a knowledgeable, willing buyer in an arm’s length transaction at the date of valuation, in accordance with International Valuation Standards as set out by the International Valuation Standards Committee”.

In short current valuations are based on inflated values.

So Moody’s structural shift to higher growth is really higher growth from bigger acquisition of debts even seen from a micro or company-to-company perspective.

Sure markets may continue to rise, but so will risks.

To paraphrase John Maynard Keynes, markets can remain irrational longer than one can stay solvent

[1] New York Times Moody’s Gives Philippines Investment-Grade Rating October 3, 2013

[2] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Bank Lending Expands Further in August September 30, 2013

[3] See Phisix: The Myth of the Consumer ‘Dream’ Economy July 22, 2013

[4] See Does The Government Deserve Credit Over Philippine Economic Growth? May 31, 2013

[5] National Statistical Coordination Board Household Final Consumption Expenditure 2nd Quarter 2013 Gross National Income & Gross Domestic Product by Expenditure Shares

[6] Wikipedia.org Publilius Syrus Quotes

[7] Wikipedia Euripides Misattributed

[8] Biblegateway.com Proverbs 16:18 (New International Version)

[9] Bloomberg Indonesia Regains Investment Grade at Moody’s After 14 Years January 19, 2012

[10] see Is Indonesia ASEAN’s Canary in the Coal Mine? August 2, 2013

[11] Economic Times Moody's raises India to investment grade January 11, 2013

[12] see Warren Buffett & co. Abandons ‘Buy India’ Theme September 27, 2013

[13] Bloomberg.com Record Defaults Seen on $40 Billion Recast Loans: India Credit September 30, 2013

[14] Bloomberg.com Indonesia Rating Raised by S&P to Highest Since '97 Asian Financial Crisis April 8, 2011

[15] Xinhua.net Impact of S&P downgrade on Indonesia temporary: central bank deputy governor, May 3, 2013

[16] Businessworld India India Downgrade Risk Higher Than For Indonesia: S&P – September 3, 2013

[17] Wall Street Journal Real Times Economics Don’t Rule Out an Asia Banking Crisis, S&P Says. October 3, 2013

[18] Bank of International Settlements BIS Quarterly Review International banking and financial market developments June 2013 p.17-18

[19] see IMF Declares: Philippines Insulated to the Fed's Taper-Exit September 25, 2013

[20] Asian Development Bank Developing Asia Slowing Amid Global Financial Jitters October 2, 2013

[21] Asian Development Bank Developing Asia Slowing Amid Global Financial Jitters October 2, 2013

[22] Wikipedia.org Great Recession in Asia

[23] Asian Development Bank FINANCIAL REPORT 2012 p 54-55

[24] Roman Frydman and Michael D. Goldberg Did Capitalism Fail? Project Syndicate September 13, 2013

[25] Wikipedia.org Credit rating agencies and the subprime crisis

[26] Wikipedia.org Start of the Great Depression

[27] Marc Flandreau Do good sovereigns default? Lessons of history p.21 Sovereign risk: a world without risk-free assets? Proceedings of a seminar on sovereign risk including contributions by central bank governors and other policy-makers, market practitioners and academics Basel, 8–9 January 2013 Monetary and Economic Department July 2013

[28] Wall Street Journal U.S. Sues S&P Over Ratings February 5, 2013

[29] The Guardian S&P sues US government over alleged retaliation for AAA credit downgrade September 4, 2013

[30] Interaksyon.com Govt spent P500 million to build Palawan naval base for US -- leftist fishermen's group October 6, 2013

[31] see Why San Miguel Corporation Looks Vulnerable September 23, 2013

[32] Inquirer.net Gokongwei buys 27% stake in Meralco September 30, 2013

[33] Wikipedia.org Eike Batista

[34] See How Leverage Affected Brazilian Billionaire Eike Batista’s Fortunes March 19, 2013

[35] Bloomberg.com OGX Upheaval Portends Deeper Bond Loss for Pimco: Brazil Credit September 30, 2013

[36] Business Insider And as went Eike, so went Brazil. The Complete Story Of How Brazilian Tycoon Eike Batista Lost 99% Of His $34.5 Billion Fortune October 3, 2013

[37] Wikipedia.org History Northern Rock

[38] Steve H. Hanke A Threadneedle Street Kerfuffle Cato Institute February 10, 2013

[39] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff This Time is Different Eight Centuries of Financial Folly xlii-xliii Princeton University

[40] Forbes.com Henry Sy & family Profile

[41] PSE.com.ph SM Investments Corporation

[42] PSE.com.ph SM Investments Corporation 2nd Quarter Report SEC Form 17-Q June 30, 2013

[43] PSE.com.ph SM Investments Corporation 2012 Annual Report SEC Form 17-A Annual Report December 31, 2012

[44] Ibid SM 2nd Quarter Report p .38

On Friday October 4, 2013, the Philippines ETF, EPHE, rose 2.3%,

ReplyDeleteBut then on Monday October 7, 2013, Jennifer Carinci of Yahoo’s Hot Stock Minute reported immediately before the market open ... Markets Around The World Are Reacting Negatively To The Lack Of Progress Out Of Washington On Budget Talks Over The Weekend ... Japan's Nikkei lost one-percent and Europe is down across the board as the world watches the stalled U.S. budget talks. Here at home futures are indicating a rough open, poised to open lower by nearly 1%.

Please consider that Fiat money died Friday September 20, 2013, with World Stocks, VT, Major World Currencies, DBV, and Emerging Market Currencies, CEW, trading lower, as Jesus Christ is operating in dispensation, as presented by the Apostle Paul in Ephesians 1:10, that is in administrative oversight of all things economic and political, and has pivoted the world out of liberalism and into authoritarianism, and as such the stock market has turned from bull to bear with the Too Big To Fail Banks, RWW, and Regional Banks, KRE, trading lower in value. Those ETF sectors which rallied over the last year and countries which rallied, from late June 2013 to late September, 2013, seen in this Finviz Screener, will be trading lower from the Tuesday October 1, 2013 rally, on competitive currency devaluation and on the exhaustion of the world central banks’ monetary authority, as investors come to greater realization that the US Fed’s monetary policies have crossed the Rubicon of sound monetary policy, and have made “money good” investments bad.

The Fed be dead. Charles Hugh-Smith of OfTwoMinds blog, writes in Zero Hedge, The Fed Bubble Era Is Over. This is seen in the Too Big To Fail Banks, RWW, trading lower from their rally highs. And Asset Managers such as BlackRock, BLK, and Eaton Vance, EV, that coined liberalism’s wealth, are trading lower as well. Now under authoritarianism, the policies of nannycrats and technocrats, working in schemes of regional integration, will underwrite economic activity.

Debt deflation, specifically competitive currency devaluation, has commenced, terminating liberalism’s fiat wealth investments in Nation Investment, EFA, and Small Cap Nation Investment, IFSM, and Emerging Market Investment, EEM, such as Egypt, EGPT, Argentina, ARGT, Thailand, THD, India Small Caps, SCIN, Brazil Small Caps, EWZS, Turkey, TUR, and Philippines, EPHE.

The decline in the price of Gold, $GOLD, since late August 2013, is a buying opportunity, as the Gold ETF, GLD, is in an Elliott Wave 3 Up, from its early July 2013 bottom of 117.5, as is seen its Weekly Finviz Chart. The Elliott Wave 3 Ups, are the most dramatic of all economic waves, and create the bulk of wealth gains, of all of the ascending five waves.

On Thursday, October 3, 2013, Spot Gold, $GOLD, closed at $1,316, with support lower at $1,300 and $1,275, and $1,250. The chart of the Gold ETF, GLD, rose slightly, to the edge of a massive consolidation triangle, to close at 127, from which it will either break out, or break lower to 125, 122 or 120. Either way, it is wise to Dollar Cost Average, an investment in the purchase of gold bullion, as in the age of authoritarianism, the possession of gold and diktat, will be the two forms of sovereign and sustainable wealth.