``The confusion of inflation and its consequences in fact can directly bring about more inflation.”-Ludwig von Mises

Every time financial markets endure a convulsion, many in the mainstream scream “DEFLATION”!

Like Pavlov’s dogs, such reaction signifies as reflexive response to conditioned stimulus, otherwise known as ‘classical conditioning’ or ‘Pavlovian reinforcement’.

Where the dogs in the experiment of Russian Nobel Prize winner Ivan Pavlov would salivate, in anticipation of food, in response to a variety of repeated stimulus applied (although popularly associated with the ringing of bells, but this hasn’t been in Ivan Pavlov’s account of experiments), the similar reflexive interpretation by the mainstream on falling markets is to allege association deflation as the cause.

Not All Bear Markets Are Alike

Yet not all bear markets are alike (see figure 1)

Figure 1 Economagic: S&P 500, CRB Commodity Index and 10 year treasury yields

Figure 1 Economagic: S&P 500, CRB Commodity Index and 10 year treasury yields

As one would note, the bear markets of the 70s came in the face of higher treasury coupon yields, represented by yields of 10 year treasuries (green line), which accounted for high inflation. This era of ‘high inflation-falling market’ phenomenon (or stagflation) is especially amplified in the recessions of 1974, 1980 and 1982 (shaded areas) as markets have been accompanied by soaring commodity prices (CRB Index-red line).

Thereby, the 1970s accounted for ‘deflation’ in terms of stock prices, borrowing the definition of the mainstream, amidst a high inflation environment, as referenced by rising consumer prices. As you would also note, the term ‘deflation’ is being obscured and deliberately misrepresented, since markets then, adversely reacted to the recessions brought about by a high inflation environment.

I’d also like to point out that surging inflation and rising stocks can be observed in 1975-1981, in spite of the 1980 recession. Although of course, the real returns were vastly eroded by the losses in purchasing power of the US dollar.

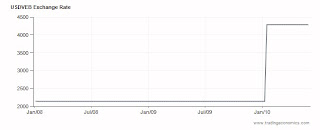

But in anticipation to the objection that high interest rates and high inflation extrapolate to falling stock markets, this isn’t necessarily true. As shown in the above, stocks can serve as an inflation hedge. And one can see a present day paradigm of this ‘surging inflation-rising stock markets’ dynamic unfolding in Venezuela!

Comparing 2010 To 2008

We always say that markets operate in different environments, such that overreliance on historical patterns could prove to be fatal. While markets may indeed rhyme or have some similarities, the outcomes may not be the same, for the simple reason that people may react differently even to parallel conditions.

For us, what is important is to anticipate how people would possibly react to the incentives provided for by current operating conditions.

We have been saying that this isn’t 2008. There is no better proof than to show how markets have responded differently even if many are conditioned to see the same (see figure 2) out of bias.

Figure 2: stockcharts.com: Market Volatility of 2008 and 2010

Figure 2: stockcharts.com: Market Volatility of 2008 and 2010

If one would account for the major difference between 2008 and 2010, it is that markets today appear to be pre-empting a 2008 scenario.

In 2008 (chart on the left window represents the activities of the year 2008), the post Lehman bankruptcy saw the S&P crash first before other markets followed, particularly oil (WTIC), and the Fear Index (VIX).

Even the US 10 year treasury yields (TNX) reacted about a month AFTER the crash in the S&P 500. This belated impact could be due to the spillover effects from the large build up of Excess Reserves (ER) to interbank lending rates as the increased in supply lowered rates at the front end, aside from ‘flight to safety’ reasons, which curiously emerged a little past the peak of the crash.

This time around (right window is the 2010 year-to-date performance), the market’s reaction has been almost simultaneous, this perhaps partly reflects on the Pavlov conditioned stimulus. And this could be the reason why many cry out “deflation”, when they seem to be deeply confused about the referencing of the term.

As we’d like to repeat, falling markets don’t reflexively account for ‘deflation’. Dogs do not think, but we do; therefore, we must learn to distinguish from the fallacies of ‘conditioned stimulus’ with that of the real events.

Besides, the fixation on ‘conditioned stimulus’ can account for, in behavioural science, as ‘anchoring’ effect, or where people’s tendency is to “rely too heavily, or "anchor," on a past reference or on one trait or piece of information when making decisions (also called "insufficient adjustment")”. In short, trying to simplify analysis by means heuristics through anchoring is likely to be flawed one. And investors would only lose money from sloppy thinking.

Yet it is also worth pointing out that price level conditions of 2008 appear to be different.

In today’s market tumult, the fear index (VIX) has been rising but is still far away from the highs of 2008; where the highs of today are the low of 2008! Moreover while oil prices have dramatically fallen, an equally swift reversal seems to be in place!

Gold Sets The Pace

Figure 3: stockcharts.com: The Faces of Gold and Silver in 2008 and 2010

Figure 3: stockcharts.com: The Faces of Gold and Silver in 2008 and 2010

Another feature in 2008 which looks distinct today is the reactions in the precious metal markets (see figure 3).

In 2008 (left window), gold prices reacted instantaneously with the collapse in the S&P 500, but recovered about a month after, just as other markets displayed the aftershocks. Gold’s recovery portended a strong rebound in risks assets thereafter.

In 2010 (right window), we seem to be seeing an abridged (déjà vu?) version of 2010 for gold only. Gold appears to have responded in the same fashion by falling with the initial shock in global stock markets. But this seems to be ephemeral as gold prices appears to have bounced back strongly.

Yet Gold prices are only a stone throw’s distance from its record nominal highs. And if Greece would serve as an indicator of the direction of Gold’s prices, which reportedly were recently priced at 40% premium of the current spot prices or at $1,700 per ounce, then we could see gold prices closing this gap over the coming months.

Nevertheless, if inflation and deflation are defined in the context of changes in the purchasing power of money (the exchange ratio between money and the vendible goods and commodities), then gold, which isn’t a medium of exchange today, but a reserve asset held only central banks, are unlikely to function as a deflation hedge for the simple reason that our monetary system operates under a legal tender based fiat ‘paper’ money standard.

In an environment where people scramble for cash or see an enormous increase in the demand for cash balances, gold which isn’t money (again in the context of medium of exchange), won’t serve as a hedge. It is counterintuitive to think why people should buy gold when cash is what is being demanded.

Figure 4: Uncommon Wisdom: Rising Gold Prices In Major Currencies

Figure 4: Uncommon Wisdom: Rising Gold Prices In Major Currencies

Hence rising gold prices represents either expectations of increases in inflation or symptomatic of a burgeoning monetary disorder. And since gold prices are up relative to all major currencies (see figure 4), then obviously, it would appear to be the latter.

So it would be another flagrant self-contradiction to argue for ‘deflation’ when markets are signalling possible distress on the current currency system.

And when people lose trust in money, this is not because of ‘deflation’ (where people have more trust in it), but because of inflation—the loss of purchasing power.

One very good example should be Venezuela. As Venezuela’s President Hugo Chavez regime seems hell bent to turn her country into a full fledged socialism, the bolivar, Venezuela’s currency, seem in a crash mode. Capital flight has been worsening in the face of soaring inflation. The Chavez regime is reportedly trying to arrest ‘inflation’ and the crashing ‘bolivar’ by raiding the foreign exchange black market. Mr. Chavez does not tell the public that his government has been printing money like mad.

One objection would be that the US isn’t Venezuela, but this would be a non-sequitur, the point is people flee money because of inflation fears and not due to ‘deflation’ expectations. So rising gold prices are indicative of monetary concerns and not of deflation.

The Difference Of Inflation And Deflation

On a special note, I’d like to point out that it is not only wrong to attribute the impact of deflation and inflation to unemployment as similar, this is plain hogwash and signifies as misleading interpretation of theory.

Here, deflation is being referenced as consequence of prior policy actions of inflationism, which leads to unemployment. In other words, unemployment is the result of unwinding of malinvestments from previous bubble policies from the government which isn’t caused by ‘deflation’ per se.

Where the rise in purchasing power means cheaper goods and services or where people can buy more stuff, how on earth can buying more stuff (deflation) and buying less stuff (inflation) be deemed as equal?

Besides, based on the political aspects of the distribution of the credit process, inflation benefits debtors at the expense of the creditors, and vice versa for deflation. As Ludwig von Mises clearly explained,

``Many groups welcome inflation because it harms the creditor and benefits the debtor. It is thought to be a measure for the poor and against the rich. It is surprising to what extent traditional concepts persist even under completely changed conditions. At one time, the rich were creditors, the poor for the most part were debtors. But in the time of bonds, debentures, savings banks, insurance, and social security, things are different. The rich have invested their wealth in plants, warehouses, houses, estates, and common stock and consequently are debtors more often than creditors. On the other hand, the poor-except for farmers—are more often creditors than debtors. By pursuing a policy against the creditor one injures the savings of the masses. One injures particularly the middle classes, the professional man, the endowed foundations, and the universities. Every beneficiary of social security also falls victim to an anti-creditor policy.

``Deflation is unpopular for the very reason that it furthers the interests of the creditors at the expense of the debtors. No political party and no government has ever tried to make a conscious deflationary effort. The unpopularity of deflation is evidenced by the fact that inflationists constantly talk of the evils of deflation in order to give their demands for inflation and credit expansion the appearances of justification.” (bold highlights mine)

And this is apparently true today. Governments (global political leaders and the bureaucracy), the global banking and financial system and other political special interest groups (e.g. labor union in the US), which have benefited from redistributive “bailout” policies, have done most of the borrowing (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Businessinsider: Total Debt To GDP by Major World Economies

Figure 5: Businessinsider: Total Debt To GDP by Major World Economies

Yet, the current inflationist policies, e.g. zero interest rates, quantitative easing, bailouts, subsidies and etc.., have been designed to filch savings of the poor and the middle class to secure the interests of these debtors.

So deflation isn’t a scenario that would be easily embraced by these interest groups, who incidentally controls the geopolitical order. Where deflation would reduce their present privileges ensures that prospective policy actions will be skewed towards the path of more ‘inflationism’.

Hence the political aspects of credit distribution, variances in the changes in purchasing power from politically based policies and the ramifications of inflationism does not only translate to a difference in the impact of inflation and deflation on every aspect of the markets and the economy, but importantly, tilts the odds of policies greatly towards inflationism. And eventually these policies will be reflected and/or vented on the markets.

For deflation to take hold would extrapolate to a major shift in the mindset of the mainstream politics.

Again deflation-phobes try to justify inflationism by the use of specious, deceptive and fallacious reasoning.

Groping For Explanation And The Bubble Mechanism

Another reason why today is going to be different from 2008, is that during the last crisis, the public single-mindedly dealt with the busting of the US housing bubble. First it was the collapse of mortgage lenders, then the investment banks, and the eventual repercussion to the US and global economies.

Today, the public seems confounded about the proximate causes of market volatility; there have been many, including the default risks of Greece, a banking system meltdown in the Eurozone, dismemberment or collapse of the EURO (!!!), another housing crash in the US, a China crash, and for fans of current events the standoff in the Korean Peninsula!

And all these groping in the dark for an answer or for an explanation to the current market circumstances implies rationalization or information bias arising from “people’s curiosity and confusion of goals when trying to choose a course of action”.

When the public seems perplexed about the real reasons, then this volatility is likely a false signal or a noise than an inflection point.

Moreover, the alleged collapse of the Euro seems the most outrageous and symptomatic of extreme pessimism. Not that I believe in the viability of the Euro, I don’t. But such myopic assumptions ignore some basic facts, such as the recently reactivated swap lines by the US Federal Reserve--which incidentally have been insignificantly tapped, to which could possibly be indicative of less anxiety; according to the Wall Street Journal ``reduced demand indicates that conditions are stable enough that overseas banks aren’t willing to tap into the swaps”--and that the IMF will contribute to the “bailout” of the Eurozone, which makes the Euro bailout a global action mostly led by the US.

Of course if the conditions will worsen in Europe, then it is likely that the US Federal Reserve may reduce its penalty rate to these emergency facilities to encourage increased access.

All these simply reveals of the cartel structure of global central banking system. This means that central banks around the world will likely work to buttress each other, as we are seeing now, to ring fence the banking system of any major economy from a collapse that could lead to a cross country contagion.

The Wall Street Journal quotes, Federal Reserve of St. Louis President James Bullard, ``Major nations “have made it very clear over the course of the last two years that they will not allow major financial institutions to fail outright at this juncture.” Since these “too-big-to-fail guarantees are in place, the contagion effects are much less likely to occur.” (emphasis added)

The sentiment of Mr. Bullard illuminates on the prevailing mindset of the monetary and political policymakers. Hence governments will continue to inflate, which has been the case, as we have rightly been arguing.

However, inflation as a policy is simply unsustainable. Hence, in my view, the current paper money system will likely tilt towards a disintegration sometime in the future. That crucial ordeal is not a matter of IF but a question of when. Of course, the other alternative, that could save the system, would be through defaults. But since debt defaults are likely to reduce the political and financial privileges of those in and around the seat of power, it is likely a contingent or an action of last recourse.

This means that default, may be an option after an aborted attempt to ‘hyper or super’ inflate the system. Where the consequences may be socially traumatic that would lead to a change in the outlook in public sentiment, only then will these be reflected on the polity.

Yet, both these scenarios aren’t likely to happen this year or the next, for the simple reason that consumer inflation is yet suppressed, which is likewise reflected on current levels of interest rates. And these artificially low rates allow governments more room to adopt popular inflationist measures.

And 2008 could be used as an example for this boom bust mechanism, where oil prices soared to a record high of $147 per barrel even as the economy and the markets were being blighted by strains from the housing bubble bust. The record high oil prices, weakening of the economy, the spreading of the unwinding of malinvestments and the mounting balance sheet problems of the banking and financial system all combined to serve as manifestations of a tightened monetary environment that seem to have immobilized the hands of officials relative to market forces. Eventually the culmination of these concerted pressures was seen in the ghastly crash of global asset markets.

Again this isn’t the case today.

Influences Of The Yield Curve, China and Political Markets

This also leads us back to our long held argument about the impact of the yield curve to the markets and to the economy.

The Federal Reserve of Cleveland demonstrates the effects of the yield curve to the real economy (see figure 6)

Figure 6 Federal Reserve of Cleveland: The Yield Curve May 2010

Figure 6 Federal Reserve of Cleveland: The Yield Curve May 2010

Inverted yield curves have been quite reliable indicators of recessions and economic recovery or the business cycles.

Yield curves tend to have 2-3 years lag. The recession of 2008-2009, was clearly in response to or foreshadowed by an inverted yield curve in early 2006-2007 (right window). Since the world went off the Bretton Woods gold dollar standard in 1971, the yield curve cycles have had very strong correlations, if not perfect (left window) with market activities and the real economy.

It is true that the past may have different influences in today’s yield curve dynamics, as Joseph G. Haubrich and Kent Cherny of the Federal Reserve of Cleveland writes,

``Differences could arise from changes in international capital flows and inflation expectations, for example. The bottom line is that yield curves contain important information for business cycle analysis, but, like other indicators, they should be interpreted with caution.”

Nevertheless in contrast to the mainstream, which has patently ignores this important variable and instead continually blether about liquidity trap and ‘deflation’, one reason to depend on the reliability of the yield curve is due to the “profit spread”.

Again we quote anew Murray N. Rothbard,

``In their stress on the liquidity trap as a potent factor in aggravating depression and perpetuating unemployment, the Keynesians make much fuss over the alleged fact that people, in a financial crisis, expect a rise in the rate of interest, and will therefore hoard money instead of purchasing bonds and contributing toward lower rates. It is this “speculative hoard” that constitutes the “liquidity trap,” and is supposed to indicate the relation between liquidity preference and the interest rate. But the Keynesians are here misled by their superficial treatment of the interest rate as simply the price of loan contracts. The crucial interest rate, as we have indicated, is the natural rate—the “profit spread” on the market. Since loans are simply a form of investment, the rate on loans is but a pale reflection of the natural rate. What, then, does an expectation of rising interest rates really mean? It means that people expect increases in the rate of net return on the market, via wages and other producers’ goods prices falling faster than do consumer goods’ prices.”

In short, interest rates which fuels boom-bust cycles, also represents the profit spreads in the credit market as seen in the context of ``saving, investment, and the rate of interest are each and all simultaneously determined by individual time preferences on the market.”

And considering that all the major economies are now on zero bound interest rates (which is likely to be extended), has steep yield curves and are engaged in some form of quantitative easing, while interest rates remain low, as seen in the long term yields of major economies sovereign papers and muted consumer price inflation, it is my impression that there won’t be any crashes, as peddled by the perma bears.

Of course, this is conditional to the surfacing of tail risks such as political accidents e.g. outbreak of military clash in the Korean Peninsula, unilateral call by Greece to default or secede from the European Union, and a crash in China etc...

And speaking of China we learned the authorities have shifted gears from “tightening” back to an “accommodating” policy (see figure 7).

Figure 7: Businessinsider: China Is Back To Pumping Liquidity Into Its Financial System

Figure 7: Businessinsider: China Is Back To Pumping Liquidity Into Its Financial System

Again this gives more credence to our view that policymakers approach social problems by throwing money at them, by regulation or by taxation or by a change in leadership. All of which are meant to resolve the visible short term effects at the expense of the future.

Finally, Ludwig von Mises on the deliberate distortions of the terms of inflation and deflation,

``The terms inflationism and deflationism, inflationist and deflationist, signify the political programs aiming at inflation and deflation in the sense of big cash-induced changes in purchasing power.”

In short, everything about the markets is now politics.

Wikipedia.org, Classical Conditioning

Wikipedia.org, Ivan Pavlov

Wikipedia.org, Lists of Cognitive Bias

See In Greece, Gold Prices At US $1,700 Per Ounce!

Brodrick, Sean, Get Your Gold and Silver Coins Now, Uncommon Wisdom

Businessweek, Chavez Says Unregulated Currency Market May Disappear

Mises, Ludwig von Interventionism: An Economic Analysis by Ludwig von Mises

Businessinsider, Here's Everyone Who Would Get Slammed In A Spanish Debt Crisis

See On North Korea's Brinkmanship

Wikipedia.org, Information Bias

Wall Street Journal Blog, A Look Inside the Fed’s Balance Sheet

See The Euro Bailout And Market Pressures

Wall Street Journal Blog, Fed’s Bullard: Europe Woes Unlikely to Trigger Another Recession

See Why The Greece Episode Means More Inflationism

See Global Markets Violently Reacts To Signs Of Political Panic

See Influences Of The Yield Curve On The Equity And Commodity Markets

Rothbard, Murray N. America’s Great Depression

Ibid

Businessinsider: China Is Back To Pumping Liquidity Into Its Financial System

See Mainstream’s Three “Wise” Monkey Solution To Social Problems

Mises, Ludwig von Cash-Induced and Goods-Induced Changes in Purchasing Power, Human Action, Chapter 17 Section 6