Five Nobel Prize economists call for an end to the 'war on drugs' in a new report from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).Ending the Drug Wars: Report of the LSE Expert Group on the Economics of Drug Policy outlines the enormous negative outcomes and collateral damage from the ‘war on drugs’ and includes a call on governments from five Nobel Prize economists[1] to redirect resources away from an enforcement-led and prohibition-focused strategy, toward effective, evidence-based policies underpinned by rigorous economic analysis

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Thursday, May 08, 2014

5 Nobel Prize Winners Call for the End of the War on Drugs

Friday, November 09, 2012

An Emergent Trend on the War on Drugs? Mexico Considers Legalization

The decision by voters in Colorado and Washington state to legalize the recreational use of marijuana has left Mexican President-elect Enrique Peña Nieto and his team scrambling to reformulate their anti-drug strategies in light of what one senior aide said was a referendum that “changes the rules of the game.”It is too early to know what Mexico’s response to the successful ballot measures will be, but a top aide said Peña Nieto and members of his incoming administration will discuss the issue with President Obama and congressional leaders in Washington this month. The legalization votes, however, are expected to spark a broad debate in Mexico about the direction and costs of the U.S.-backed drug war here.Mexico spends billions of dollars each year confronting violent trafficking organizations that threaten the security of the country but whose main market is the United States, the largest consumer of drugs in the world.

Thursday, July 05, 2012

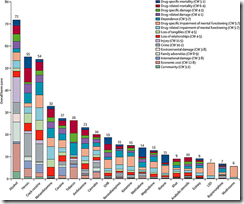

Chart of the Day: Alcohol Deadlier than Illegal Substance?

From the Business Insider

We've covered the study by former UK drug czar David Nutt that found alcohol to be the most dangerous drug in the country by far when 20 drugs were rated on how much harm each caused to users and to others.

Nutt just came out with a new book, Drugs Without the Hot Air: Minimizing the Harms of Legal and Illegal Drugs, and last week told the Guardian that research into mental illness is hampered by the prohibition of drugs such as psilocybin and LSD.

If true then this is yet another falsification of popular wisdom about the supposed lethality of drugs, and more importantly, the political justification behind the war on drugs.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Video: The Economics of Drug Prohibition, Why Prohibition Laws Fail

Despite the mountains of regulations, and the multitude of arrests and incarcerations, drug use has been rapidly expanding globally. On the contrary, these constitutes as failures of such regulations.

Yet this is does not just apply to drugs but almost to every other instances of prohibitions on social vices, e.g. smoking, prostitution, gambling (e.g. Philippine jueteng) and etc...

[As a side note, I might add that people who argue from the high perch of morality are those mostly out there to get social acceptability or "likes" from the uninformed than to objectively discuss the merits or demerits of such regulations]

The following video from LearnLiberty.org explains the economics of prohibition and why such laws engenders adverse unintended effects than what is supposed to be accomplished. (hat tip Professor Mark Perry)

In its history, America has experienced two major periods of drug prohibition. This first was the Federal alcohol prohibition from 1920-1933. The second is the current war on drugs, which began in 1971.In short, not only does prohibition statutes corrupt a society, at worst they kill.

According to Prof. Angela Dills, during these periods of prohibition in America, both homicide rates and police enforcement costs increased. This makes sense, as prohibitions never actually eliminate use. Rather, prohibitions convert peaceful and legal markets into black markets. In black markets, when disputes arise over sales territory, product quality, or money, the government legal system is not available. This forces drug dealers to resolve disputes on their own, which often leads to violence.

The violence of black markets, along with the enforcement of drug policy, attracts the attention of law enforcement. Law enforcement is costly, and the time spent enforcing drug laws could have been spent preventing other crimes like murder, theft, and rape. Drug prohibition not only generates more violence and increases the cost of law enforcement; it also distracts law enforcement and puts citizens at greater risk of crime.

Monday, April 30, 2012

Quote of the Day: The Bottom One Percent

We hear a lot about the top 1%. We don't hear a lot about the bottom 1%. There are about 313 million people in America today. 1% of 313 million is 3,130,000. In our prisons today are 2,200,000 people. So the people in prison are 2/3 of one percent. And their wages are typically about 23 cents an hour. They are, essentially, the bottom 1%.

Many of them are there for violent crimes, theft, fraud, and other such things. But hundreds of thousands of them are there for buying, selling, or producing illegal drugs. The drug war has put them there. And we taxpayers are paying $30,000 a year and more to keep them there.

So let me get this straight: high-income people are paying lots of taxes so that the government can put poor people in prison and keep them poor or put non-poor people in prison and make them poor.

We hear the occupy people advocate taxing the top 1% more. I've got a better idea: let's tax the top 1% less--they're already paying a disproportionately high share of taxes--and let a few hundred thousand of the bottom one percent out of prison and out of their grinding poverty in prison.

That’s from Professor David Henderson.

Saturday, March 17, 2012

War on Drugs: Richard Branson Asked President Obama for a Weed

Writes the Politico,

When you go to a White House state dinner and you’re lucky enough to get some face time with the president, what do you ask the president?

“I asked him if I could have a spliff,” businessman and Virgin Group honcho Richard Branson told a crowd gathered at The Atlantic’s Washington offices Thursday, the day after attending the dinner for British Prime Minister David Cameron.

“But they didn’t have any,” Branson continued, according to a video of the event as he recalled his effort to procure weed the night before at the White House.

What’s he smoking? Well, Branson is a longtime advocate for the legalization of marijuana — and an admitted recreational pot puffer — and spoke at an Atlantic Exchange panel discussion titled “Benchmarching the War on Drugs.” Branson appeared alongside The Atlantic’s Washington Editor-At-Large Steve Clemons and Ethan Nadelmann, the executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance.

The Atlantic crowd guffawed mightily, which is appropriate: Branson was quick to note that he was joking.

It’s presidential election season, so President Obama’s state dinner has likely been about raising campaign funds. Here we can see how the political leadership can be swayed (or captured) by the interests of big businesses--you scratch my back and I'll scratch yours.

But the most important point here is that even through a joke, the Mr. Branson seems to have undauntedly delivered the incisive message of legalizing drugs.

Ironically, President Obama has admitted to have used drugs in his youth. (hat tip Business Insider)

Saturday, November 26, 2011

War on Drugs: Misplaced ‘Follow the Money’ Priorities by Cops Results to More Crimes

You think the war on drugs make society peaceful? Think again.

Police officers, like any human being, also follow the money. But unlike us, since they are armed by mandate, they may use the law for their self-interest or benefit at our expense.

From Radley Balko of the Huffington Post (bold emphasis added) [hat tip Don Boudreaux]

As Jessica Shaver and I chat at a coffee shop in Chicago's north-side Andersonville neighborhood, a police car pulls into the parking lot across the street. Then another. Two cops get out, lean up against their cars, and appear to gaze across traffic into the store. At times, they seem to be looking directly at us. Shaver, who works as an eyebrow waxer at a nearby spa, appears nervous.

"See what I mean? They follow me," says Shaver, 30. During several phone conversations Shaver told me that she thinks a small group of Chicago police officers are trying to intimidate her. These particular cops likely aren't following her; the barista tells me Chicago cops regularly stop in that particular parking lot to chat. But if Shaver is a bit paranoid, it's hard to blame her.

A year and a half ago she was beaten by a neighborhood thug outside of a city bar. It took months of do-it-yourself sleuthing, a meeting with a city alderman and a public shaming in a community newspaper before the Chicago Police Department would pay any attention to her. About a year later, Shaver got more attention from cops than she ever could have wanted: A team of Chicago cops took down her door with a battering ram and raided her apartment, searching for drugs.

Shaver has no evidence that the two incidents are related, and they likely aren't in any direct way. But they provide a striking example of how the drug war perverts the priorities of America's police departments. Federal anti-drug grants, asset forfeiture policies and a generation of battlefield rhetoric from politicians have made pursuing low-level drug dealers and drug users a top priority for police departments across the country. There's only so much time in the day, and the focus on drugs often comes at the expense of investigating violent crimes with victims like Jessica Shaver. In the span of about a year, she experienced both problems firsthand….

In other words priority has been skewed towards milking out drug felons at the expense of other peacekeeping tasks. All because of following the money

Again from Huffington Post…

Arresting people for assaults, beatings and robberies doesn't bring money back to police departments, but drug cases do in a couple of ways. First, police departments across the country compete for a pool of federal anti-drug grants. The more arrests and drug seizures a department can claim, the stronger its application for those grants.

"The availability of huge federal anti-drug grants incentivizes departments to pay for SWAT team armor and weapons, and leads our police officers to abandon real crime victims in our communities in favor of ratcheting up their drug arrest stats," said former Los Angeles Deputy Chief of Police Stephen Downing. Downing is now a member of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, an advocacy group of cops and prosecutors who are calling for an end to the drug war…

At the same time, there's increasing evidence that the NYPD is paying less attention to violent crime. In an explosive Village Voice series last year, current and former NYPD officers told the publication that supervising officers encouraged them to either downgrade or not even bother to file reports for assault, robbery and even sexual assault. The theory is that the department faces political pressure to produce statistics showing that violent crime continues to drop. Since then, other New Yorkers have told the Voice that they have been rebuffed by NYPD when trying to report a crime.

The most perverse policy may be asset forfeiture. Under civil asset forfeiture, police can seize property from people merely suspected of drug crimes. So long as police can show even the slightest link of drug activity to a car, some cash, or even a home, they can seize it. In the majority of cases, most or all of the seized cash goes back to the police department. In some cases, the department has taken possession of cars as well, but generally non-cash property is auctioned off, with the proceeds then going back to the department. An innocent person who has property seized must go to court and prove his property was earned legitimately, even if he was never charged with a crime. The process of going to court can often be more expensive than the value of the property itself.

Asset forfeiture not only encourages police agencies to use resources and manpower on drug crimes at the expense of violent crimes, it also provides an incentive for police agencies to actually wait until drugs are on the streets before making a bust. In a 1994 study reported in Justice Quarterly, criminologists J. Mitchell Miller and Lance H. Selva watched several police agencies delay busts of suspected drug dealers in order to maximize the cash the department could seize. A stash of illegal drugs isn't of much value to a police department. Letting the dealers sell the drugs first is more lucrative.

Read the rest here

Again like all human beings, the police resorts to actions based on priorities or on personal value scales. And arbitrary laws affect their underlying incentives to act as public officials. Apparently the war on drugs tend to misplace their priorities, all at the expense of society.

Friday, June 17, 2011

Ex-US President Jimmy Carter: Call Off the Global Drug War

Former US President Jimmy Carter joins the bandwagon calling for an end to the Global War on Drugs.

Writing in the New York Times, (bold emphasis mine)

IN an extraordinary new initiative announced earlier this month, the Global Commission on Drug Policy has made some courageous and profoundly important recommendations in a report on how to bring more effective control over the illicit drug trade. The commission includes the former presidents or prime ministers of five countries, a former secretary general of the United Nations, human rights leaders, and business and government leaders, including Richard Branson, George P. Shultz and Paul A. Volcker.

The report describes the total failure of the present global antidrug effort, and in particular America’s “war on drugs,” which was declared 40 years ago today. It notes that the global consumption of opiates has increased 34.5 percent, cocaine 27 percent and cannabis 8.5 percent from 1998 to 2008. Its primary recommendations are to substitute treatment for imprisonment for people who use drugs but do no harm to others, and to concentrate more coordinated international effort on combating violent criminal organizations rather than nonviolent, low-level offenders...

Drug policies here are more punitive and counterproductive than in other democracies, and have brought about an explosion in prison populations. At the end of 1980, just before I left office, 500,000 people were incarcerated in America; at the end of 2009 the number was nearly 2.3 million. There are 743 people in prison for every 100,000 Americans, a higher portion than in any other country and seven times as great as in Europe. Some 7.2 million people are either in prison or on probation or parole — more than 3 percent of all American adults!

Some of this increase has been caused by mandatory minimum sentencing and “three strikes you’re out” laws. But about three-quarters of new admissions to state prisons are for nonviolent crimes. And the single greatest cause of prison population growth has been the war on drugs, with the number of people incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses increasing more than twelvefold since 1980.

Not only has this excessive punishment destroyed the lives of millions of young people and their families (disproportionately minorities), but it is wreaking havoc on state and local budgets. Former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger pointed out that, in 1980, 10 percent of his state’s budget went to higher education and 3 percent to prisons; in 2010, almost 11 percent went to prisons and only 7.5 percent to higher education.

There’s been a snowballing awareness that prohibition laws, particularly the war on drugs, eventually ends up with MORE accrued adverse effects than the intended benefits.

Unfortunately, events will turn for the worst before such feckless laws will get repealed.

And the sad part is that taxpayers everywhere will endure most of the burdens, aside from the extended risks of societal degeneration from the prospects of escalation of violence, rampant corruption, obstacles to medical advancement, loss of civil liberty, police brutality and many other injustices from war on drugs related regulatory abuses.

Noble intentions will not substitute for economic reality, that’s why whether prohibition is applied to drugs, illegal gambling such as jueteng (Philippines), prostitution or etc..., they are all bound for failure.

Friday, June 03, 2011

Global War on Drugs a Failed Policy

Here is the statement from a report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, a nineteen-member panel that includes, among others, world figures such as former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan, former Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso and former NATO Secretary General Javier Solana. The current Prime Minister of Greece, George Papandreou is also a signatory which makes him the only representative of government.

(bold emphasis mine)

The global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world. Fifty years after the initiation of the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and 40 years after President Nixon launched the US government’s war on drugs, fundamental reforms in national and global drug control policies are urgently needed.

Vast expenditures on criminalization and repressive measures directed at producers, traffickers and consumers of illegal drugs have clearly failed to effectively curtail supply or consumption. Apparent victories in eliminating one source or trafficking organization are negated almost instantly by the emergence of other sources and traffickers. Repressive efforts directed at consumers impede public health measures to reduce HIV/AIDS, overdose fatalities and other harmful consequences of drug use. Government expenditures on futile supply reduction strategies and incarceration displace more cost-effective and evidence-based investments in demand and harm reduction.

Cato’s Juan Carlos Hidalgo writes, (bold highlights added)

The 20-page report says all the right things: prohibition has failed in tackling global consumption of drugs, and has instead led to the creation of black markets and criminal networks that resort to violence and corruption in order to carry out their business. This drug-related violence now threatens the institutional stability of entire nations, particularly in the developing world. Also, prohibition has caused the stigmatization and marginalization of people who use illegal drugs, making it more difficult to help people who are addicted to drugs. The report also denounces what it properly calls “drug control imperialism,” that is, how the United States has “worked strenuously over the last 50 years to ensure that all countries adopt the same rigid approach to drug policy.”

In the recommendations section, the report praises the experience of Portugal with drug decriminalization, mentioning Cato’s study on the subject. But perhaps more importantly, it states that drug legalization “is a policy option that should be explored with the same rigor as any other.” Until now, similar reports have denounced the war on drugs and perhaps called for the decriminalization of marijuana and other soft drugs, but they also have stopped short of mentioning drug legalization as a policy alternative.

Prohibition laws represents an example of noble intent, whose visible effects, fails to account for the cost of the unseen—the economic effects and people’s response to such repressive laws.

Saturday, December 26, 2009

When Vice Isn't A Crime: The Philosophical Flaws Of Prohibition Laws

In short, people tend to oversimplistically associate vice with crime-even if both are different.

Vices are acts by which man hurts himself in pursuit of short term happiness, whereas crimes are acts by which man hurts or harms the personal property of another.

Lysander Spooner in a fantastic philosophical discourse disproves such popular fallacies... (all bold emphasis mine)

``But it will be asked, "Is there no right, on the part of government, to arrest the progress of those who are bent on self-destruction?

``The answer is that government has no rights whatever in the matter, so long as these so-called vicious persons remain sane, compos mentis, capable of exercising reasonable discretion and self-control. Because, so long as they do remain sane, they must be allowed to judge and decide for themselves whether their so-called vices really are vices; whether they really are leading them to destruction; and whether, on the whole, they will go there or not.

``When they shall become insane, non compos mentis, incapable of reasonable discretion or self-control, their friends or neighbors, or the government, must take care of them, and protect them from harm, and against all persons who would do them harm, in the same way as if their insanity had come upon them from any other cause than their supposed vices.

``But because a man is supposed, by his neighbors, to be on the way to self-destruction from his vices, it does not, therefore, follow that he is insane, non compos mentis, incapable of reasonable discretion and self-control, within the legal meaning of those terms. Men and women may be addicted to very gross vices, and to a great many of them — such as gluttony, drunkenness, prostitution, gambling, prize fighting, tobacco chewing, smoking, and snuffing, opium eating, corset wearing, idleness, waste of property, avarice, hypocrisy, etc., etc. — and still be sane, compos mentis, capable of reasonable discretion and self-control, within the meaning of the law.

``And so long as they are sane, they must be permitted to control themselves and their property, and to be their own judges as to where their vices will finally lead them. It may be hoped by the lookers-on, in each individual case, that the vicious person will see the end to which he is tending, and be induced to turn back.

``But if he chooses to go on to what other men call destruction, he must be permitted to do so. And all that can be said of him, so far as this life is concerned, is that he made a great mistake in his search after happiness, and that others will do well to take warning by his fate. As to what may be his condition in another life, that is a theological question with which the law, in this world, has no more to do than it has with any other theological question, touching men's condition in a future life.

``If it be asked how the question of a vicious man's sanity or insanity is to be determined, the answer is that it is to be determined by the same kinds of evidence as is the sanity or insanity of those who are called virtuous, and not otherwise. That is, by the same kinds of evidence by which the legal tribunals determine whether a man should be sent to an asylum for lunatics, or whether he is competent to make a will, or otherwise dispose of his property. Any doubt must weigh in favor of his sanity, as in all other cases, and not of his insanity.

``If a person really does become insane, non compos mentis, incapable of reasonable discretion or self-control, it is then a crime on the part of other men, to give to him or sell to him the means of self-injury. There are no crimes more easily punished, no cases in which juries would be more ready to convict, than those where a sane person should sell or give to an insane one any article with which the latter was likely to injure himself."

Read the rest of lenghty but highly insightful treatise here.

In other words, prohibition unworthily sacrifices personal liberty and private property for control.

Again Spooner, ``The object aimed at in the punishment of vices is to deprive every man of his natural right and liberty to pursue his own happiness under the guidance of his own judgment and by the use of his own property"

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Europe's Cannabis Usage and Drug Decriminalization

According to the Economist, ``OVER a fifth of Europeans have taken cannabis at some point in their lives, according to new report on illegal drug use from the EMCDDA, the EU's drug-monitoring arm. Over 30% of Danes, French and Italians aged between 15 and 64 have puffed on a joint. But perhaps for Danes it is just a phase: the Italians, Spanish, French and Czechs are most likely to have dabbled with cannabis in the recent past. Levels of cannabis use are still high but may be declining, says the report. Recent studies suggest that the drug's popularity is waning among the younger generation."

While it is good news to know that Cannabis usage have generally been declining especially among the younger generation, what seems noteworthy is that both Netherlands and Portugal, which has partly decriminalized drug use, is shown to have relatively low instance of usage. This defies common objections where legalization would lead to a drug use explosion.

See our earlier related posts:

Drug Decriminalization: Regulation Versus Prohibition,

Drug Decriminalization Caravan Gets Rollin',

War on Drugs: Learning From Portugal's Drug Decriminalization

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Drug Decriminalization: Regulation Versus Prohibition

Some notes:

1. Regulation versus Prohibition

``The Dutch classify marijuana as a "soft drug," which means that, like alcohol and tobacco, it is best regulated through controlled distribution. "Hard drugs," such as cocaine and heroin, remain illegal. But personal drug use is more a health matter than an arrestable offense.

``Even the Amsterdam police want to keep the coffee shops open. "Why push drug use underground?" asked Christian Koers, the police chief responsible for Amesterdam's red-light district. "Then you cannot control it, and it becomes more popular and more dangerous. "

``This idea -- that drugs are both enjoyable and dangerous and thus better regulated than prohibited by government and sold by criminals -- seems common-sense enough, even in America. Until now, the main opposition to a state's right to legalize marijuana has been the federal government. But last week, in a major policy shift, the U.S. Justice Department instructed federal prosecutors not to focus on "individuals whose actions are in clear and unambiguous compliance with existing state laws providing for the medical use of marijuana."

2. Illegal Dealing Spawns Violence

``There is little violence surrounding the private drug trade between friends, coworkers and family members. The real drug problem, along with addictive heroin and crystal meth, is illegal public dealing. In public drug markets, signs of violence are everywhere: Intimidating groups of youths stand on corners under graffiti memorializing slain friends; addicts roam the streets and squat in vacant buildings; "decent" people stay inside when gunshots ring out in the night."

3. Addressing Crime Is Distinct From Controlling Vice

``In another neighborhood in Amsterdam, a man caught breaking into cars was released pending trial. The arresting officer returned to him, along with his shoelaces and personal property, his heroin and drug tools. I was amazed. The officer admitted he wasn't supposed to do that; heroin is illegal. But the officer had thought it through: "As soon as he runs out of his heroin, he'll break into another car to get money for his next hit."

``For the addict, the problem was drugs. But for the police officer, the problem was crime. It made no sense, the officer told me, to take the drugs and hasten the addict's next crime. The addict was not a criminal when he had drugs (beyond possessing them); he was a criminal when he didn't have drugs.

``I asked the officer if giving drugs to addicts sends the wrong message. He said his message was simple: "Stop breaking into cars!" With a subtle smirk in my direction, he added, "It is very strange that a country as violent as America is so obsessed with jailing drug addicts." Indeed, Dutch policymakers plan, regulate, fix and pragmatically debate harms and benefits. Police in the Netherlands are not involved in a drug war; they're too busy doing real police work."

4. Decriminalization Doesn't Promote Usage, Regulation Reduces Chaos

``The results are telling. In America, 37 percent of adults have tried marijuana; in the Netherlands the figure is 17 percent. Heroin usage rates are three times higher in the United States than in the Netherlands. Crystal meth, so destructive here, is almost nonexistent there. By any standard -- drug usage rates, addiction, homicides, incarceration and dollars spent -- America has lost the war on drugs.

``And just as escalating the drug war over the past three decades hasn't caused a decrease in supply and demand, there's no good reason to believe that regulating drugs instead of outlawing them would cause an increase. If it did, why are drug usage rates in the Netherlands lower? People start and stop taking drugs for many different reasons, but the law seems to be pretty low on the list. Ask yourself: Would you shoot up tomorrow if heroin were legal"

``Nobody wants a drug free-for-all; but in fact, that's what we already have in many communities. What we need is regulation. Distribution without regulation equals criminals and chaos -- what police see every day on some of our streets. People will buy drugs because they want to get high, and the question is only how and where they will buy them.

5. Learning From History

``History provides some lessons. The 21st Amendment ending Prohibition did not force anybody to drink or any city to license saloons. In 1933, after the failure to ban alcohol, the feds simply got out of the game. Today, they should do the same -- and last week the Justice Department took a very small step in the right direction."

Read the entire article here

Hat tip Mark Perry

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Drug Decriminalization Caravan Gets Rollin'

Resources uneconomically spent for prohibition and detention should instead be diverted into education, treatment and the protection of private property.

As New York Times' Nicolas Kristof in a recent highly articulate commentary, (bold highlight mine)

``Look, there’s no doubt that many people in prison are cold-blooded monsters who deserve to be there. But over all, in a time of limited resources, we’re overinvesting in prisons and underinvesting in schools.

``Indeed, education spending may reduce the need for incarceration. The evidence on this isn’t conclusive, but it’s noteworthy that graduates of the Perry Preschool program in Michigan, an intensive effort for disadvantaged children in the 1960s, were some 40 percent less likely to be arrested than those in a control group.

``Above all, it’s time for a rethink of our drug policy. The point is not to surrender to narcotics, but to learn from our approach to both tobacco and alcohol. Over time, we have developed public health strategies that have been quite successful in reducing the harm from smoking and drinking.

``If we want to try a public health approach to drugs, we could learn from Portugal. In 2001, it decriminalized the possession of all drugs for personal use. Ordinary drug users can still be required to participate in a treatment program, but they are no longer dispatched to jail.

``“Decriminalization has had no adverse effect on drug usage rates in Portugal,” notes a report this year from the Cato Institute. It notes that drug use appears to be lower in Portugal than in most other European countries, and that Portuguese public opinion is strongly behind this approach.

Now, it appears that indeed several Latin American Countries have begun to assimilate the Portugal Experience; Mexico and Argentina has opened their doors for the less antagonistic option by decriminalizing drugs.

According to Juan Carlos Hidalgo of Cato, (bold highlights mine)

``Following in Mexico’s footsteps last week, the Supreme Court of Argentina has unanimously ruled today on decriminalizing the possession of drugs for personal consumption.

``For those who might be concerned with the idea of an “activist judiciary,” the Court’s decision was based on a case brought by a 19 year-old who was arrested in the street for possession of two grams of marijuana. He was convicted and sentenced to a month and a half in prison, but challenged the constitutionality of the drug law based on Article 19 of the Argentine Constitution:

``The private actions of men which in no way offend public order or morality, nor injure a third party, are only reserved to God and are exempted from the authority of judges. No inhabitant of the Nation shall be obliged to perform what the law does not demand nor deprived of what it does not prohibit.

``Today, the Supreme Court ruled that personal drug consumption is covered by that privacy clause stipulated in Article 19 of the Constitution since it doesn’t affect third parties. Questions still remain, though, on the extent of the ruling. However, the government of President Cristina Fernández has fully endorsed the Court’s decision and has vowed to promptly submit a bill to Congress that would define the details of the decriminalization policies.

``According to some reports, Brazil and Ecuador are considering similar steps. They would be wise to follow suit."

We, Filipinos, should learn from their experiences.

Thursday, June 25, 2009

War on Drugs: Learning From Portugal's Drug Decriminalization

In an earlier post,[see Nicolas Kristof: Why The War On Drugs Is A Failure], we dealt with the unorthodox suggestions of how to deal with the Drug menace.

Drugs isn't just a social problem, it encapsulates economic, political and the regulatory dimensions. Hence, the required approach should be holistic than simply "moralistic".

Of course, theories won't be persuasive if unmatched by actual experience, thereby, Portugal's 7 years experience on the drug decriminalization path could serve as noteworthy paradigm.

The essence of drug decriminalization seems simple: it transforms government's role from strong arm "fear-based" antagonistic approach into "mentorship" guidance, where government spends the substance of its efforts in education and treatment than from prohibition.

Moreover, the diminished operating costs enables the freeing up or shifting of government resources into more constructive means to deal with the problem, which in essence lowers the barriers of collaboration with the public.

And because the relationship switches to a more congenial climate, the impact from enforcement tends to have a high degree of success.

In short, from fear based approach to a cooperation, sympathy and treatment based solution.

The following is an article, which includes a video interview from Reason.tv ., explains the Portugal experience....

(all bold highlights mine)

Glenn Greenwald is a civil rights attorney, a blogger for Salon, and the author of a new Cato Institute policy study called “Drug Decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for Creating Fair and Successful Policies.” The paper examines Portugal’s experiment with decriminalizing possession of drugs for personal use, which began in 2001. Nick Gillespie, editor of reason.com and reason.tv, sat down with Greenwald in April.

Q: What is the difference between decriminalization and legalization?

A: In a decriminalized framework, the law continues to prohibit drug usage, but it’s completely removed from the criminal sphere, so that if you violate that prohibition or do the activity that the law says you cannot do you’re no longer committing a crime. You cannot be turned into a criminal by the state. Instead, it’s deemed to be an administrative offense only, and you’re put into an administrative proceeding rather than a criminal proceeding.

Q: What happened in Portugal?

A: The impetus behind decriminalization was not that there was some drive to have a libertarian ideology based on the idea that adults should be able to use whatever substances they want. Nor was it because there’s some idyllic upper-middle-class setting. Portugal is a very poor country. It’s not Luxembourg or Monaco or something like that.

In the 1990s they had a spiraling, out-of-control drug problem. Addiction was skyrocketing. Drug-related pathologies were increasing rapidly. They were taking this step out of desperation. They convened a council of apolitical policy experts and gave them the mandate to determine which optimal policy approach would enable them to best deal with these drug problems. The council convened and studied all the various options. Decriminalization was the answer to the question, “How can we best limit drug usage and drug addiction?” It was a policy designed to do that.

Q: One of the things you found is that decriminalization actually correlates with less drug use. A basic theory would say that if you lower the cost of doing drugs by making it less criminally offensive, you would have more of it.

A: The concern that policy makers had, the frustration in the 1990s when they were criminalizing, is the more they criminalized, the more the usage rates went up. One of the reasons was because when you tell the population that you will imprison them or treat them as criminals if they identify themselves as drug users or you learn that they’re using drugs, what you do is you create a barrier between the government and the citizenry, such that the citizenry fears the government. Which means that government officials can’t offer treatment programs. They can’t communicate with the population effectively. They can’t offer them services.

Once Portugal decriminalized, a huge amount of money that had gone into putting its citizens in cages was freed up. It enabled the government to provide meaningful treatment to people who wanted it, and so addicts were able to turn into non–drug users and usage rates went down.

Q: What’s the relevance for the United States?

A: We have debates all the time now about things like drug policy reform and decriminalization, and it’s based purely in speculation and fear mongering of all the horrible things that are supposedly going to happen if we loosen our drug laws. We can remove ourselves from the realm of the speculative by looking at Portugal, which actually decriminalized seven years ago, in full, [use and possession of] every drug. And see that none of that parade of horribles that’s constantly warned of by decriminalization opponents actually came to fruition. Lisbon didn’t turn into a drug haven for drug tourists. The explosion in drug usage rates that was predicted never materialized. In fact, the opposite happened.

Watch Glenn Greenwald and Reason.tv's Nick Gillespie discuss both the lessons from Portugal and Barack Obama's disappointing performance so far on drug policy, executive power, and civil liberties by clicking on this link

Monday, June 15, 2009

Nicolas Kristof: Why The War On Drugs Is A Failure

The consequence of which was not only a failure of regulation to achieve its goal, but that it had created more problems than what it was meant to achieve, particularly black market for bootleg liquors, gangsters, mass violence, mass murder and etc.

Obviously the end result was that the Act was lifted in 1933.

Now, New York Times' high profile columnist Nicolas Kristof makes a pitch on why the same legal efforts to purge drug use seems to achieve parallel unintended consequences akin to the defunct Volstead Act.

This excerpt from his excellent article "Drugs Won The War" (all bold emphasis mine)

``This year marks the 40th anniversary of President Richard Nixon’s start of the war on drugs, and it now appears that drugs have won.

``“We’ve spent a trillion dollars prosecuting the war on drugs,” Norm Stamper, a former police chief of Seattle, told me. “What do we have to show for it? Drugs are more readily available, at lower prices and higher levels of potency. It’s a dismal failure.”

``For that reason, he favors legalization of drugs, perhaps by the equivalent of state liquor stores or registered pharmacists. Other experts favor keeping drug production and sales illegal but decriminalizing possession, as some foreign countries have done.

``Here in the United States, four decades of drug war have had three consequences:

``First, we have vastly increased the proportion of our population in prisons. The United States now incarcerates people at a rate nearly five times the world average. In part, that’s because the number of people in prison for drug offenses rose roughly from 41,000 in 1980 to 500,000 today. Until the war on drugs, our incarceration rate was roughly the same as that of other countries.

Second, we have empowered criminals at home and terrorists abroad. One reason many prominent economists have favored easing drug laws is that interdiction raises prices, which increases profit margins for everyone, from the Latin drug cartels to the Taliban. Former presidents of Mexico, Brazil and Colombia this year jointly implored the United States to adopt a new approach to narcotics, based on the public health campaign against tobacco. [see below-BTe]

``It’s now broadly acknowledged that the drug war approach has failed. President Obama’s new drug czar, Gil Kerlikowske, told the Wall Street Journal that he wants to banish the war on drugs phraseology, while shifting more toward treatment over imprisonment.

Read the rest here

The 3 former presidents of Latin American Nations mentioned above by Mr. Kristoff are Mr. Fernando Cardoso the former president of Brazil, Mr. Cesar Gaviria former president of Colombia and Mr. Ernesto Zedillo former president of Mexico, whom also made the same argument early this year at the Wall Street Journal.

``The war on drugs has failed. And it's high time to replace an ineffective strategy with more humane and efficient drug policies. This is the central message of the report by the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy we presented to the public recently in Rio de Janeiro.

``Prohibitionist policies based on eradication, interdiction and criminalization of consumption simply haven't worked. Violence and the organized crime associated with the narcotics trade remain critical problems in our countries. Latin America remains the world's largest exporter of cocaine and cannabis, and is fast becoming a major supplier of opium and heroin. Today, we are further than ever from the goal of eradicating drugs.

Read the rest here

Be reminded that laws or regulations no matter how noble its goal, can have unintended or long term "unseen" consequences.

And at the end of the day, regulations fall into the taxonomy of economics. The success of which would be determined by the tradeoffs between long term costs and benefits.