``The European capital market institutions would not be able (or even willing) to step up to the plate and negotiate a restructuring. The ECB is not allowed to. And the EC is not up to it. There is an alternative -- the IMF has specific experience in this regard. But, allowing the IMF in would be an admission that the Euro area has not quite made it as currency union. The IMF, given its historical origin with exchange rate mechanisms, would convey a message that the big Euro players would not like to see. It would tar the reputation of the Euro even if there are no contagion effects on other PIIGS. Moreover, allowing Greece out of the Euro (or kicking) it out would be even worse. That is why, I think, the Germans will pay up. They will pay to maintain the reputation of the Euro. Americans underestimate the commitment to the Euro.” –Paul Wachtel Thoughts on Greece's debt problems

Prior to last week’s intermission, we noted that like the Dubai debt crisis, the Greek dilemma would seem like a political issue more than an economic one and therefore, as we suggested, would be resolved politically.

And by politically, we meant that arguments for sound policies or by imposing harsh or rigorous discipline against a wayward member of the EU would be subordinate to the practice of inflationism.

And as per the mainstream, the most recent volatility in the global markets had been mostly attributed to either the prospects of a contagion from the risks of a Greece default or from the attempts of China to wring out inflation out of its system.

Nevertheless, we have not been convinced by verity of the alleged cause.

While key benchmarks across asset markets have indeed broadly deteriorated then, which somewhat did raise some worries on my part, the correlation and the supposed causation did not seem to square [see Global Market Rout: One Market, Two Tales].

If indeed there had been a generalized anxiety over a contagion of rising default risks from sovereign debts, then sovereign CDS AND sovereign YIELDS, aside from corporate and bank lending rates would have spiked altogether!

In addition, considering the scenario of a run from sovereign securities, the contagion should have been largely a regional dynamic and paper currencies would not have been seen as the safe shelter, since the major currencies of the world have all similarly afflicted by the same disease!

What happened instead was a palpable shift to the currency (US dollar) of the lesser affected nation (the US) which somewhat resembled a “flight to safety” paradigm of 2008. With the trauma from the recent crisis along with automatic stimulus response [as discussed in What Has Pavlov’s Dogs And Posttraumatic Stress Got To Do With The Current Market Weakness?] some have mistakenly labeled the recent events as the unwinding US dollar carry trade.

Yet, as CDS and yields went on the opposite course, Baltic stock markets soared and gold plummeted validating our observation that the precious metal, which has served as man’s money throughout the ages, has been exhibiting a tight correlation with the Euro or a proxy thereof, instead of deflation or inflation signs [see When Politics Ruled The Market: A Week Of Market Jitters]. This tight correlation appears to have been broken last week! (see figure 3)

Figure 3: stockcharts.com: Gold-Euro Break, US 10 Year Yield, JP Morgan Emerging Debt Fund

The contour of the Euro and Gold trendlines has been the same over the 6 months up until last week!

Since gold has served as lead indicator of asset markets since the depths of 2008, including the recent selloffs, any resumption of an upward trend by gold is likely to be signs that asset markets will be headed higher soon.

Ergo, Gold above 1,120 should likely serve as my trigger for a buy on equity markets.

Moreover the major US sovereign benchmark, the 10 year Treasury yield (TNX), in spite of the recent stock market setback has remained stubbornly high. Also the JP Emerging Market Debt Fund (JEMDX), in spite of the recent China and Greek jitters, remains buoyant.

In other words, those expecting a repeat of 2008 or of a deflation scenario appear to be in a wrongheaded direction.

What seems to be in place is that the markets seem to be looking for a reason to retrench or has been reacting to the discordant tones from the mixed messages transmitted by the political and bureaucratic authorities. In short, if markets had been recently buoyant out of a flood of global liquidity then qualms over a liquidity rollback appear to be the major concern.

Inherent Defects In The Euro

Any major liquidity rollback for developed economies would most likely be deferred, with the Greek and the PIIGS issues signifying as one of the principal reasons.

Remember since the PIIGS is a political issue then any attempt to resolve the Greek crisis will be political.

Professor Paul Wachtel in a New York University forum captures it best, ``It is not Greece, it is the Euro. A troubled small country can be shrugged off but a currency area is either whole or not. The Germans will pay up to keep the Euro area in tact.”

True. A united Europe has been a longstanding project since the close of World War II. Monetary integration has been in the works through the European Monetary System since March of 1979.

So the Euro isn’t just a symbolical currency that can easily be jettisoned, instead it is a sense of pride for the major European economies that make up the core of the European Union. Hence it won’t be easy to dismantle a pet project for Europe’s social democrats.

However since the Euro is another monetary experiment it comes with inherent flaws in it.

For instance, the inclusion of Greece to the European Union has effectively bestowed subsidy privileges to her by the European Central Bank (ECB) even prior to this crisis via an intraregion carry trade.

Where the interest rate spread of Greek sovereign instruments had been wide relative to core Euro members, European banks bought Greek bonds and used them as collateral to extract additional loans from the ECB. Spendthrift socialist Greece, in turn, took advantage of this easy access to money to fund lavish public expenditures.

As Philip Bagus explains, ``The banks buy the Greek bonds because they know that the ECB will accept these bonds as collateral for new loans. As the interest rate paid to the ECB is lower than the interest received from Greece, there is a demand for these Greek bonds. Without the acceptance of Greek bonds by the ECB as collateral for its loans, Greece would have to pay much higher interest rates than it does now. Greece is, therefore, already being bailed out.

``The other countries of the eurozone pay the bill. New euros are, effectively, created by the ECB accepting Greek government bonds as collateral. Greek debts are monetized, and the Greek government spends the money it receives from the bonds to secure support among its population.”

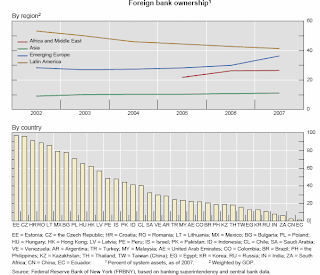

The latest US centered bubble exacerbated the carry trade and the intraregion subsidies of the PIIGS which eventually rendered European banks as highly sensitive to a PIIGS default (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Bloomberg: Shot Gun Wedding

According to Bloomberg’s Chart of the Day, ``Banks in Germany and France alone have a combined exposure of $119 billion to Greece and $909 billion to the four countries, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements. Overall, European banks have $253 billion in Greece and $2.1 trillion in the so-called PIGS.”

So not unlike the US, the European Union will most likely persist in subsidizing subprime PIIGS and the European banking system at the expense of the rest of its society.

And also not different from the US, the risks of unsustainable welfare states will likely be a part of the currency and asset equation.

NYU’s Mario Rizzo bluntly writes, ``People like to deny reality when it is unpleasant. This is not just a problem of bad leadership. It is a problem that goes to the heart of the fantasy world the typical voter lives in. Buy reality bites. Let’s see how it does so in the next few years.” (bold highlight mine)

Moreover, the underlying systemic subsidies incent European member state beneficiaries to expand spending. Obviously such feedback loop mechanism of incremental subsidies and deficit spending will ultimately be untenable.

Again from Philip Bagus, ``For the member states in the eurozone, the costs of reckless fiscal behavior can also, to some extent, be externalized. Any government whose bonds are accepted as collateral by the ECB can use this printing press to finance its expenditures. The costs of this strategy are partly externalized to other countries when the newly created money bids up prices throughout the monetary union.

``Each government has an incentive to accumulate higher deficits than the rest of the eurozone, because its costs can be externalized. Consequently, in the Eurosystem there is an inbuilt tendency toward continual losses in purchasing power. This overexploitation may finally result in the collapse of the euro.” (bold emphasis mine)

So perhaps it wouldn’t be systemic rigidities that could undo the Euro, as preeminent monetarist Milton Friedman warned about [or the tradeoff between ``greater discipline and lower transaction costs outweigh the loss from dispensing with an effective adjustment mechanism”] but the untenable cross subsidies and systemic inflationism inherent within the system.

Easy Monetary Policies To Continue

And the political response has been as what we had expected.

An article from Bloomberg says Europe will use former US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson’s “Bazooka” approach to deal with Greece, ``European leaders closed ranks to defend Greece from the punishment of investors in a pledge of support that may soon be tested. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and her counterparts yesterday pledged “determined and coordinated action” to support Greece’s efforts to regain control of its finances. They stopped short of providing taxpayers’ money or diluting their own demands for the country to cut the European Union’s biggest budget deficit.”

Like short selling, the blame has always been pinned on the markets. However, as discussed above, the woes of the PIIGS exhibits a structurally flawed monetary system.

The fact that Greece fudged its numbers to get into the Euro membership serves as damning evidence of EU’s incompetence. Investors don’t just punish nations without any basis. Investors get burned for making the wrong decisions.

On the other hand, bilking taxpayers, misrepresentation and mismanagement are enough justifications for punishment, not only from investors but from the resident political constituency. True, international sanctions won’t likely work as policymakers are too tied up rescuing each other.

Of course, tightening of monetary policies today won’t help the cause of the EU or the US from executing bailouts and rescues of their political patrons. Hence we can expect deferred “exit strategies” and even extended quantitative easing programs.

Oh, did I just mention the US as possibly help fund a Greece bailout? Yes, apparently. This according to Financial Times, `` European governments are expected to turn increasingly to US investors to help them meet their funding requirements as record levels of bond issuance make it harder to attract buyers.” (bold highlight mine)

So whether it be the IMF (where the US has the largest exposure representing 17% of voting rights) or direct participation from US investors we can expect somewhat the US to be a tacit part of the rescue team. Sssssssshhhhh.

Perhaps, some Asian nations as China may take part in it too.

What do you expect, it’s a paper money system! Government central banks can simply print money and channel them into sectors or economies in dire straits, in the hope that the money printing has neutral effects.

All the imbalances we’ve just spelled out here is a medium to long term perspective, which means they aren’t likely to unravel anytime soon.

But it is one of the risks that should be reckoned with overtime.

For the meantime, the triumphalism of the Philosopher’s Stone or the alchemy of turning lead into gold will likely still work its interim or immediate wonder. That’s why it has been the preferred du jour priority option by policymakers.

And importantly, that’s why it gives confidence to the global political authorities to do all their redistributive programs.

Meanwhile, expansionary policies from the EU and the US are likely to continue. And this should help support the asset markets.