-Oil prices are three times what they were in 2000, making cargo-ship fuel much more expensive now than it was then.-The natural-gas boom in the U.S. has dramatically lowered the cost for running something as energy-intensive as a factory here at home. (Natural gas now costs four times as much in Asia as it does in the U.S.)-In dollars, wages in China are some five times what they were in 2000—and they are expected to keep rising 18 percent a year.-American unions are changing their priorities. Appliance Park’s union was so fractious in the ’70s and ’80s that the place was known as “Strike City.” That same union agreed to a two-tier wage scale in 2005—and today, 70 percent of the jobs there are on the lower tier, which starts at just over $13.50 an hour, almost $8 less than what the starting wage used to be.-U.S. labor productivity has continued its long march upward, meaning that labor costs have become a smaller and smaller proportion of the total cost of finished goods. You simply can’t save much money chasing wages anymore.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Saturday, January 12, 2013

Reasons for US Insourcing

Monday, October 01, 2012

Currency Manipulation and the Politics of Neo-Mercantilism

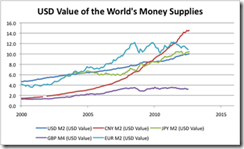

The dollar maintains its reserve currency status because it is the least worst of the major four currencies – the US dollar, the British pound, the Japanese yen, and the euro. All four of these currencies are now suffering the effects of a stimulative, expansive, and QE-oriented monetary policy.We must now add the Swiss franc as a major currency, since Switzerland and its central bank are embarked on a policy course of fixing the exchange rate between the franc and the euro at 1.2 to 1. Hence the Swiss National Bank becomes an extension of the European Central Bank, and therefore its monetary policy is necessarily linked to that of the eurozone…When you add up these currencies and the others that are linked to them, you conclude that about 80% of the world’s capital markets are tied to one of them. All of the major four are in QE of one sort or another. All four are maintaining a shorter-term interest rate near zero, which explains the reduction of volatility in the shorter-term rate structure. If all currencies yield about the same and are likely to continue doing so for a while, it becomes hard to distinguish a relative value among them; hence, volatility falls.The other currencies of the world may have value-adding characteristics. We see that in places like Canada, Sweden, and New Zealand. But the capital-market size of those currencies, or even of a basket of them, is not sufficient to replace the dollar as the major reserve currency. Thus the dollar wins as the least worst of the big guys.Fear of dollar debasement is, however, well-founded. The United States continues to run federal budget deficits at high percentages of GDP. The US central bank has a policy of QE and has committed itself to an extension of the period during which it will preserve this expansive policy. That timeframe is now estimated to be at least three years. The central bank has specifically said it wants more inflation. The real interest rates in US-dollar-denominated Treasury debt are negative. This is a recipe for a weaker dollar. The only reason that the dollar is not much weaker is that the other major central banks are engaged in similar policies.

First, they serve as lenders of last resort, which in practice means bailouts for the big financial firms. Second, they coordinate the inflation of the money supply by establishing a uniform rate at which the banks inflate, thereby making the fractional-reserve banking system less unstable and more consistently profitable than it would be without a central bank (which, by the way, is why the banks themselves always clamor for a central bank). Finally, they allow governments, via inflation, to finance their operations far more cheaply and surreptitiously than they otherwise could.

Protectionism, often refuted and seemingly abandoned, has returned, and with a vengeance. The Japanese, who bounced back from grievous losses in World War II to astound the world by producing innovative, high-quality products at low prices, are serving as the convenient butt of protectionist propaganda. Memories of wartime myths prove a heady brew, as protectionists warn about this new "Japanese imperialism," even "worse than Pearl Harbor." This "imperialism" turns out to consist of selling Americans wonderful TV sets, autos, microchips, etc., at prices more than competitive with American firms.Is this "flood" of Japanese products really a menace, to be combated by the U.S. government? Or is the new Japan a godsend to American consumers? In taking our stand on this issue, we should recognize that all government action means coercion, so that calling upon the U.S. government to intervene means urging it to use force and violence to restrain peaceful trade. One trusts that the protectionists are not willing to pursue their logic of force to the ultimate in the form of another Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

People favor discrimination and privileges because they do not realize that they themselves are consumers and as such must foot the bill. In the case of protectionism, for example, they believe that only the foreigners against whom the import duties discriminate are hurt. It is true the foreigners are hurt, but not they alone: the consumers who must pay higher prices suffer with them.

While the size of the credit expansion that private banks and bankers are able to engineer on an unhampered market is strictly limited, the governments aim at the greatest possible amount of credit expansion. Credit expansion is the governments' foremost tool in their struggle against the market economy. In their hands it is the magic wand designed to conjure away the scarcity of capital goods, to lower the rate of interest or to abolish it altogether, to finance lavish government spending, to expropriate the capitalists, to contrive everlasting booms, and to make everybody prosperous.

Thursday, September 06, 2012

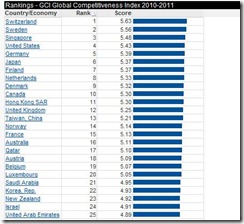

World Competitiveness: Philippines Jumps to 65th Place

The World Economic Forum (WEF) recently released, The Global Competitiveness Report for 2012-2013 which attempts to measure relative competitiveness among 144 nations that provides “insight into the drivers of their productivity and prosperity”

It is important to highlight that the competitive ranking have been defined by the WEF as

as the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. The level of productivity, in turn, sets the level of prosperity that can be earned by an economy. The productivity level also determines the rates of return obtained by investments in an economy, which in turn are the fundamental drivers of its growth rates. In other words, a more competitive economy is one that is likely to sustain growth.

Here is the roster of the top 30 most competitive nations.

Notice that the WEF says the ranking is about productivity, and not about “cheap labor”.

If competitiveness is about the “cheap labor” then the Philippines and Africa will be on top of the list. Unfortunately mainstream demagoguery has obstinately been focused on this, so as to justify the inflationist-interventionists doctrines.

Also notice that the most competitive nations have been developed economies. The GCI rankings have been closely aligned with the list of most economically free nations (Heritage Foundation: 2012 Index of Economic Freedom).

It is important to note that the above rankings are comparative or relatively based. This implies that changes in standings may not necessarily translate to advancement or deterioration in domestic policies but about quantified comparative measures.

First the good news.

According to the report, the Philippines leapt from 75th to 65th

Yet despite the huge gains, which obviously will be construed and used by the mainstream and political forces to grab credit as “achievement” for the administration, the Philippines trails vastly behind the ASEAN peers.

Curiously Africa’s Rwanda has even been ahead.

The bad news is that despite the remarkable gains, the gap in the per capita GDP figures has been widening relative to our developing Asian peers.

This means that yes the Philippines has shown material progress but such gains has not been enough to cope up with the scale of advancement in the region.

Lastly, the reason for the lag in productivity has been about over politicization of the domestic economy which has been manifested through a bloated bureaucracy, lack of infrastructure (which has been politically determined—see below), tax and labor regulations and high tax rates.

Of course corruption has still been the biggest deterrent to business. But, in truth, corruption signifies as symptoms of interventionism expressed through arbitrary policies and regulations, the bureaucracy, welfare-warfare state and state determined allocation of resources.

The informal economy, which is also a symptom of interventionism, takes up a huge chunk of economic activities. This is a clear manifestation of the failures of interventionism and of the incumbent political institutions.

Ironically the salutary conditions of the shadow economy could be suggestive of the alternative positive aspects of corruption, where people pay bribe money to authorities in order to do productive endeavors. This in spite of the major negative attribution on the survey.

The burgeoning informal gold mining sector, which comes mostly in response to recently imposed higher taxes should serve as a wonderful anecdotal example.

Yet the media and the social desirability bias afflicted pop culture cheers about the Php 407 billion proposed infrastructure or so-called “investment” spending without the realization that productive money will be diverted to the pockets of cronies (who will get the contracts), bureaucrats (who will pick the winners) and politicians (which most likely will be the source of electoral finance for the upcoming 2013 national elections).

chart from US Global Investors

All these supposed stimulus will only translate to greater inequality (enrichment of the political class and of the politically connected enterprises), more debts, higher taxes (for the middle class and the politically unconnected), more PRICE inflation (which will be blamed on the private sector) and importantly adds to the ballooning bubble dynamics driven by current easy money policies.

These so-called public work policies are a chimera, as the great Professor Ludwig von Mises explained.

The fundamental error of the interventionists consists in the fact that they ignore the shortage of capital goods. In their eyes the depression is merely caused by a mysterious lack of the people's propensity both to consume and to invest. While the only real problem is to produce more and to consume less in order to increase the stock of capital goods available, the interventionists want to increase both consumption and investment. They want the government to embark upon projects which are unprofitable precisely because the factors of production needed for their execution must be withdrawn from other lines of employment in which they would fulfill wants the satisfaction of which the consumers consider more urgent. They do not realize that such public works must considerably intensify the real evil, the shortage of capital goods.

For media and the dumb downed (“madlang people”) electorate which sees this as good news hardly understands that effects of so-called government stimulus would be based on the illusions of statistics [mainstream economic statistics are based on Keynesian formula constructs] and not from real growth.

Thus, temporary good news will eventually become long term bad news.

However, despite such realities, the relatively better competitive standings today will likely continue to improve. Again, this is hardly because of internal ‘business friendly’ improvements but because of positional standings which will mostly be determined by the political responses to the unfolding crisis abroad.

Again the WEF’s GCI

The global economy faces a number of significant and interrelated challenges that could hamper a genuine upturn after an economic crisis half a decade long in much of the world, especially in the most advanced economies. The persisting financial difficulties in the periphery of the euro zone have led to a long-lasting and unresolved sovereign debt crisis that has now reached the boiling point. The possibility of Greece and perhaps other countries leaving the euro is now a distinct prospect, with potentially devastating consequences for the region and beyond. This development is coupled with the risk of a weak recovery in several other advanced economies outside of Europe—notably in the United States, where political gridlock on fiscal tightening could dampen the growth outlook. Furthermore, given the expected slowdown in economic growth in China, India, and other emerging markets, reinforced by a potential decline in global trade and volatile capital flows, it is not clear which regions can drive growth and employment creation in the short to medium term

The big picture gives us an objective dimension of the real developments rather than fall for trap to political demagoguery

Updated to add:

I was unaware when I wrote a few hours back that the competitiveness issue accounts for today's main headline story.

Friday, May 25, 2012

Germany’s Competitive Advantage over Spain: Freer Labor Markets

When politics is involved, common sense is eschewed.

The vicious propaganda against “austerity” aims to paint the government as the only solution to the crisis, where the so-called “growth” can only be attained through additional government spending funded by more debt. Unfortunately, these politically confused people have forgotten that today’s crisis has been caused by the same factors which they have been prescribing: debt. In short, their answer to the problem of debt is to acquire more debt.

The same with clamors for crisis plagued nations to “exit” the Eurozone in order to devalue the currency. Inflating away standards of living, it is held, will miraculously solve the social problems caused by too much government interventionism that has led to inordinate debt loads.

Professor John Cochrane of the Chicago School nicely chaffs at statist overtures,

The supposed benefit of euro exit and swift devaluation is the belief that people will be fooled that the 10 Drachmas are not a "cut" like the 5 euros would be. Good luck with that.

Little has been given thought to what’s happening on the ground, particularly achieving genuine competitiveness by allowing entrepreneurs to prosper.

At the Mises Institute, Ms Carolina Carmenes and Professor Howden lucidly explains why Germany has been far more competitive than Spain, specifically in the labor markets .

Spain’s labor costs have been cheaper than Germany, yet the Germans get the jobs. Writes Ms. Carmenes and Prof Howden (bold emphasis added)

Spanish employment is now hovering around 23 percent, with over 50 percent of youths jobless. Only around 6 percent of Germans are without work, almost the lowest level in the country since reunification. This divide solidifies Spain's position among the worst-performing economies of the continent, and Germany's vaunted position as among the best.

Yet such a situation might seem paradoxical. One could, for example, look at the wage rates of the respective workers and find that low-cost Spaniards are much more affordable. Profit-maximizing businesses should be expanding their facilities to take advantage of the opportunity the Spanish crisis has provided and eschew higher-cost German labor.

While fixating on nominal labor costs might provide a compelling case for a bright Spanish future, delving into the details provides some darker figures.

Once again the German-Spain comparison shows of the myth of cheap labor

Little thought has also been given to the impact of minimum wage and excessive labor regulations which stifles investment and therefore adds to the pressures of unemployment

Again Ms. Carmenes and Prof Howden (bold emphasis added)

One of the main differences between Germany's and Spain's labor markets is their minimum-wage rates. A Spanish minimum-wage worker can expect to earn about €633 per month. Germany on the other hand enforces no across-the-board minimum wage except in isolated professions — construction workers, roofers, and electricians, as examples.

German employees are free to negotiate their salaries with their employers, without any price-fixing intervention by the government in the form of wage control. (This is not to imply that the German labor market is completely unhampered — jobs are cartelized by industry each with its own wage controls. While this cartelization is not perfect, it does at least recognize that a one-size-fits-all minimum-wage policy is not optimal for the whole country.)

As an example of the German approach to wages, consider the case of a construction worker. In eastern Germany this worker would make a minimum wage of around €9 per hour. His counterpart in western Germany would earn considerably more — almost €11 an hour. This difference allows for productivity differences to be priced separately or local supply-and-demand conditions to influence wages. Working for five days at eight hours a day would yield this German worker anywhere from €360 to €440.

It is obvious that the German weekly wage is almost as high as the monthly Spanish one. What is less obvious is why Germans do not move their facilities to lower-cost Spain.

As the old saying goes, "the more expensive you are to fire, the more expensive you are to hire." If a Spanish company decides to lay off an employee, the severance payment for most labor contracts (a finiquito in Spanish) will amount to 32 days for each year the employee has worked with the company. Although this process is not simple in Germany either, there is no legal severance requirement that companies must pay to redundant workers. The sole requirement is for ample notice to be given, sometimes up to six months in advance. If a Spanish company hires a worker who does not work out as intended, a substantial cost will be incurred in the future to offload the employee. Employers know this, and when hiring workers they exercise caution accordingly, lest this unfortunate and unplanned-for future materialize.

These factors make the perceived or expected cost of labor at times higher in Spain than in Germany, despite the actual monetary cost being lower in euro terms. This effect has been especially pronounced since the adoption of the common currency over a decade ago. As we can see below, the average cost of German labor is largely unmoved since 2000, while Spanish labor has increased about 25 percent over the same period.

When hiring a worker, the nominal wage is only half the story. The employer also needs to know how productive that worker will be. Even after we factor for the extra costs on Spanish labor, a German worker could be more costly. A firm would still choose to hire that worker if his or her productivity was greater.

As we can see in the two figures below, over the last decade a large divergence has emerged between the two countries. While German productivity has more or less kept pace with its small increases in wage rates, the Spanish story is remarkably different. Productivity has lagged, meaning that on a real basis Spanish laborers are much more costly today than they were just 10 years ago.

Of course, boom bust policies have also contributed to such imbalances. The EU integration which had the ECB inflating the system essentially pushed Spanish wages levels up substantially, thereby overvaluing Spanish labor relative to productivity and relative to the Germans and to other European nations…

In his book The Tragedy of the Euro, Philipp Bagus mentions a similar phenomenon. Bagus points to the combination of (1) the rising labor costs that result from eurozone inflation and (2) divergent productivity rates between the countries as a source of imbalance. Indeed, inflation has been one driver of rising (and destabilizing) wages in the periphery of Europe, and especially in Spain. Others include, as we have noted here, minimum wages, regulatory burdens, and severance packages that increase the potential cost of labor.

In either case the effect is the same: wage rates do not necessarily reflect the labor itself, but rather the regulation surrounding it. In Spain, this translates to noncompetitive wages. It is important to remember, though, that this does not imply that the labor itself is necessarily uncompetitive — it is price dependent after all.

Every good has its price, even labor. When prices are hindered from fluctuating to clear markets, imbalances occur. In labor markets those imbalances are unemployed people. Policies such as a one-size-fits-all minimum wage and high mandated severance packages keep the price of Spanish labor above what it needs to be to clear the market.

Until something is done to ease these policies, Spanish labor will remain uncompetitively priced. Until Spanish labor costs can be repriced competitively, Spain's masses will need to endure stifling levels of unemployment.

The only solution to the current crisis is to allow economic freedom to prevail. Of course, this means less power for the politicians and their allies which is why they won't resort to this. Their remedies will naturally be worst than the disease.

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

Proximity Based Manufacturing Supply Chains as Trend of the Future?

The Economist proposes that the current trend in global manufacturing could shift based on the following priorities, other than labor arbitrages.

-Proximity to customers

Many multinationals will continue to build most of their new factories in emerging markets, not to export stuff back home but because that is where demand is growing fastest.

-Inventory Management

Firms are also trying to reduce their inventory costs. Importing from China to the United States may require a company to hold 100 days of inventory. That burden can be handily reduced if the goods are made nearer home (though that could be in Mexico rather than in America).

Read the rest here

Ballooning inflation means not only rising wages in Emerging markets which erodes the opportunities for labor arbitrage, but may also extrapolate to substantial increases in transportation costs which could alter the cost benefits of outsourcing.

So perhaps proximity based supply chains could be a dynamic that could gain a larger role in the future.

Thursday, April 14, 2011

Global Job Markets: Specialized (Value Added) Work Means Higher Pay

Here is my favourite marketing guru, Seth Godin’s take on cheap labor… (bold emphasis mine)

When something is scarce, it's valuable. MBA's with buzzwords and the ability to raise a million dollars around some web idea are not scarce. They are fungible.

People who understand technology and are willing to bend it to their will, on the other hand, are scarce. They can't be found with a classified ad on Craigslist or in a blind project ad on eLance.

The job of the smart business person isn't to fish in waters where coders are cheap. It's to have enough initiative and vision that the best coders in the world will realize that they'll do better with you than without you.

Business people add value when they make things happen, not when they seek to hire cheap.

Cheapness isn’t everything. Job markets are a function of demand and supply. In today’s climate where global economies have been transitioning from mass production to niche markets, specialization (division of labor and comparative advantage) will be playing a much greater role in shaping job markets.

Courtesy of Kauffman Foundation

Thus, people who specialize will command higher pay. To argue that “cheapness” steal away jobs represent squishy thinking.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Reductio Ad Absurdum on Wage Disparities, Supply of Labor and Exports

In trying to demonstrate the importance of the distinction between causation and correlation, my favorite marketing guru Seth Godin asks “Does a ski trip to Aspen make you a successful bond trader, or do successful bond traders go skiing in Aspen?”

This applies to political economic analysis as well.

Mainstream analysis, particularly those of the rigid Keynesian persuasion, would take the former - ski trip to Aspen make you a successful bond trader-over the latter as the answer or correlation mistaken as causation.

Applied to the political economic sphere they would argue that in order to preserve employment at home, the policy prescription should be a mercantilistic one: inflate (currency devaluation) or impose protectionism (limiting trade via tariffs). Never mind if this flawed argument has been a discredited idea even by 18th century economists. For Keynesian mercantilists, subtraction and not addition equals prosperity (gains).

Their assumption, which mostly signifies from a reductionist perspective, oversimplifies trade as operating in fixed pie wherein one gains at the expense of the other (zero sum).

And this is supported by their rationalization which sees every economic variable as homogenous.

And through selective statistical aggregates, they derive the conclusion that only government, equipped by the knowledge on how to adjust the knobs, can rightly balance out the interest of the nation. [Applied to Seth Godin’s riddle, government should send everyone to Aspen to make them all successful bond traders!]

And also from such perspective they see employment as the only driver of businesses and of economies-forget profits, capital, productivity, property rights, market accessibility and everything else-in the rigid Keynesian world, what only counts are labor costs.

In other words, labor cost, not profits, determines investments which subsequently translate to employment. Thus for them government policies must be directed towards accomplishing this end.

It has further been alleged that the supply of labor accounts for as a vital part in determining wage levels.

The reductionism: large supply of labor equates to low wages and consequently export power.

Let’s see how true this is applied to the real world.

Since labor basically is manpower then population levels would account for as the critical denominator.

One might argue that demographic distribution per nation would be different, which is true, but the difference does not neglect the fact that population levels fundamentally determine the supply of available labor.

Here is the world’s largest population, according to Wikipedia.org,

Given the reductionism which postulates that large labor force equates to low wages, then we should expect these countries, including the US and Japan to have the lowest wage rates in the world!

Yet even without looking at wage statistics we know this to be patently false (as seen from the bigger picture)!

Since wage levels are different per nation or per locality, perhaps the best way to gauge wages would be to use minimum wages as a yardstick.

Minimum wage account for as the national mandated minimum pay levels that are directed towards the lowest skilled workers.

Going back to the mercantilist postulate, since the largest population (largest pool of available labor) per continent belongs to Asia,...

...then the mercantilist logic implies that the lowest wages should be in Asia. Chart courtesy of Geo Hive (xist.org).

Yet according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), based on median minimum wages per country (US $PPP) the lowest wages would be in South East Europe and the CIS!

Asian wages are even higher than Africa and Southeast Europe and the CIS. Another disconnect!!

In addition, if broken down on a per country basis, based on the level of minimum wages in 2007 (PPP US$).... (again from ILO)

We would find that NONE of the largest or most populous countries (all in red arrows) are at the lowest echelon, except for Bangladesh and the Russian Federation seen at the lowest decile. (Yet the latter two are NOT export giants)

In pecking order, China, Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria Pakistan and India are mostly situated at the upper segment of the lower half of the graph.

Meanwhile the Philippines can be seen on the higher second quartile, and the US having the highest minimum wages (among the highest populated nations), along with European countries.

So what this proves?

There is hardly any correlation between population levels (supply of labor) and wage levels! The assertion that supply of labor equals low wages is outrageously naive and inaccurate!

And let us further examine how these minimum wage levels impact exports. The following chart of the world’s largest exporters is from Wikipedia.org

And I would also include global competitiveness as measured by the World Economic Forum (Global Competitiveness report)

So what do we see?

We see a strong correlation between the world’s biggest exporters and the most competitive nations. And one might add to that HIGH minimum wages!

While it would be tempting to argue that high minimum wages equals strong competitiveness/exports, we would be falling for the same post hoc argument trap of misreading correlation as causation like those employed by rigid Keynesians.

The real answer to such wage disparity is the high standards of living in developed economies which arises from the greater capital stock (or productive assets in the economy) and a higher productivity of the citizenry.

As Professor Donald J. Boudreaux explains, (bold highlights mine, emphasize his)

Low-wage labor is generally not low-cost labor. The reason is that the productivity of low-wage workers in China and other developing countries is much lower than is the productivity of workers in America. While low-wage foreigners outcompete high-wage Americans at many low-skill, routine, and repetitive tasks, high-wage Americans can (and do) outcompete low-wage foreigners in those tasks that can be performed efficiently only in advanced economies that are full of the machinery and intricate infrastructure – physical, legal, and cultural – that raise wages by raising worker productivity

In short, high American wages aren’t a disadvantage; they are a happy reflection of the fact the typical American worker is a powerhouse of production.

In short to argue from a wrong premise would mean wrong conclusions.

Why?

Because for politically blinded people, their intuitive tendency is to selectively pick on events or data points (data mining, e.g. low value low skill industries, China) and deliberately misinterpret them (to create a strawman-China's low wages stealing American and Filipino jobs) in order to fit all these into their desired conclusions (cart before the horse reasoning-erect trade barriers).

They similarly deploy false generalizations based on the perceived defects interpreted as a general condition (fallacy of composition-low wages equals export strength).

These represent not only as sloppy ‘blind spot’ thinking but likewise, a reductio ad absurdum or a conclusion based on the reduction to absurdity.

Caveat emptor.

Wednesday, September 08, 2010

Quote of the Day: The Future of Labor

Here is a great post labor day quote from marketing guru Seth Godin,

In a world where labor does exactly what it's told to do, it will be devalued. Obedience is easily replaced, and thus one worker is as good as another. And devalued labor will be replaced by machines or cheaper alternatives. We say we want insightful and brilliant teachers, but then we insist they do their labor precisely according to a manual invented by a committee...

Companies that race to the bottom in terms of the skill or cost of their labor end up with nothing but low margins. The few companies that are able to race to the top, that can challenge workers to bring their whole selves--their human selves--to work, on the other hand, can earn stability and growth and margins. Improvisation still matters if you set out to solve interesting problems.

The future of labor isn't in less education, less OSHA and more power to the boss. The future of labor belongs to enlightened, passionate people on both sides of the plant, people who want to do work that matters.

In the ongoing transition to the information age, investments, trade and jobs will require increasing patterns of diversity and specialization. And as pointed out by Mr. Godin, those who focus on the mediocre will suffer from commoditized wages and profit margins and will be subjected to rigors of tight competition.

Finally, this also shows how labor, like capital, isn’t homogeneous.

Saturday, July 03, 2010

Cheap Labor Theory And Economic Growth: Philippine Edition

.bmp)

.bmp)

.bmp)

.bmp)

.bmp)