The labor gap has already caused some project delays in the private construction industry, leading to an increase in home and office prices, said Joey Bondoc, research manager at Colliers International Philippines in Manila. Of the 16,200 additional residential units that Colliers expected in Manila last year, only about 7,400 units were completed in the first three quarters.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Sunday, June 03, 2018

Philippine Competitiveness Ranking Plunges! How the Crowding Out Strains Economic Competitiveness: The Construction Industry

The labor gap has already caused some project delays in the private construction industry, leading to an increase in home and office prices, said Joey Bondoc, research manager at Colliers International Philippines in Manila. Of the 16,200 additional residential units that Colliers expected in Manila last year, only about 7,400 units were completed in the first three quarters.

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

More Devaluation Myths

Investing guru Mark Mobius, executive chairman of Templeton Emerging Markets Group says,

In some cases, a devalued currency can be an engine for future growth. A lower currency price means the nation’s exports will be more competitive (less expensive) in the global market, and imports will become more expensive, so many companies can benefit.

A discussion about currency values should include a discussion about inflation, which is closely interconnected. Inflation has been problematic for many emerging economies, and while it does seem to be ebbing temporarily in some markets, it’s important to remain vigilant about it. High inflation can cause a strong public response (even a mass uprising), as consumer purchasing power quickly erodes.

It would be patently misleading to present devaluation as a different animal from inflation. That’s because devaluation IS inflationism. Consumer price inflation signifies as the effect of prior monetary inflation.

Professor Jeffrey M. Herbener explains,

When a government announces devaluation, as the United States did in 1934 and again in 1971, it is merely recognizing the reality of the consequences of its monetary inflation. Its inflationary policy has eroded the purchasing power of its currency which will be suffered both domestically, with price inflation, and internationally, with devaluation.

The undesirable effects of monetary inflation cannot be eliminated with floating exchange rates. Then the price inflation and devaluation occur gradually instead of being bottled up behind the government’s unsustainable peg. But whether the currency is pegged, as the dollar was in the 1920s and 1930s, or floats, as the dollar has since 1971, monetary inflation and credit expansion cause a boom-bust cycle.

Yet prescribing devaluation is tantamount to, or a euphemism of saying poverty promotes growth.

By having to lower standards of living, as a consequence of the transference of resources to politicians and their cronies, people are expected to work harder in order to generate growth.

So inflationistas are essentially moral schadenfreudes—finding satisfaction in the miseries of people.

Not to mention that inflation represents highway robbery (plunder) by governments of their people.

Even the divine inspiration of statists and facists, John Maynard Keynes admitted to these. (Wikipedia.org; bold highlights original)

Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the capitalist system was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth. Those to whom the system brings windfalls, beyond their deserts and even beyond their expectations or desires, become 'profiteers,' who are the object of the hatred of the bourgeoisie, whom the inflationism has impoverished, not less than of the proletariat. As the inflation proceeds and the real value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless; and the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery.

Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.

Let’s take the Philippines as example.

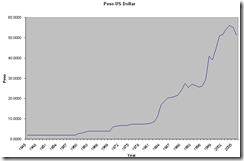

The Peso devalued from 2 pesos: 1 US dollar in 1960s to about 42 pesos to a US dollar today. This means the Peso devalued by about 4% annually.

From the perspective devaluation exponents, this should have made the Philippines an export giant. However the Philippines ranks only 57th based on 2011 data according to Wikipedia.org

Ironically, most of the top exporters are represented by ‘strong’ currencies from developed economies, and not from economies that has massively devalued their currencies as Zimbabwe.

It’s good news to see that the Philippine GDP per capital has skyrocketed from $257 in 1960 to $ 2,140.12 in 2010, according to Index Mundi.

But this only accounts for an average annual growth of about 1.7%. That’s way below the rate of devaluation (inflation) at 4%. Also the surge came amidst globalization. As a side note, to put a political spice on this, much of the increase came from the 2003 onwards.

And this has been the "magic" that has spawned PEOPLE exports or the Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) whom has been politically labeled as today’s economic heroes, out of the paucity of economic opportunities.

In reality, OFWs are MANIFESTATIONS of an uncompetitive economy borne out of interventionism and inflationism.

And much of that “economic growth” has not only emanated from OFWs, but from the INFORMAL economy which government statisticians downplays or deliberately hides behind the numbers. The informal economy has also been symptom of government failures and of the uncompetitive nature of the economy brought by sustained interventionism and inflationism.

Lastly the idea that exports or tourism benefit from the policy of poverty as a path to prosperity (devaluation) also misrepresents the reality. Devaluation or inflationism provides short term benefits at the expense of the long term.

The great Professor Ludwig von Mises exposes such deception,

If one looks at devaluation not with the eyes of an apologist of government and union policies, but with the eyes of an economist, one must first of all stress the point that all its alleged blessings are temporary only. Moreover, they depend on the condition that only one country devalues while the other countries abstain from devaluing their own currencies. If the other countries devalue in the same proportion, no changes in foreign trade appear. If they devalue to a greater extent, all these transitory blessings, whatever they may be, favor them exclusively. A general acceptance of the principles of the flexible standard must therefore result in a race between the nations to outbid one another. At the end of this competition is the complete destruction of all nations' monetary systems.

The much talked about advantages which devaluation secures in foreign trade and tourism, are entirely due to the fact that the adjustment of domestic prices and wage rates to the state of affairs created by devaluation requires some time. As long as this adjustment process is not yet completed, exporting is encouraged and importing is discouraged. However, this merely means that in this interval the citizens of the devaluating country are getting less for what they are selling abroad and paying more for what they are buying abroad; concomitantly they must restrict their consumption.

Legal plunder through currency inflationism or devaluation has neither provided long term (or lasting-sustainable) economic solutions nor has it been a moral one.

Saturday, February 11, 2012

Video: Comparing Effective Tax Rates of Corporations

It is important to point out that aside from tax policies, the policies that constitute the monetary, political, legal, bureaucratic and regulatory regimes also contributes to the economy's level of competitiveness.

Overall, the lesser involvement by the government, the more competitive the economy. In other words, economic freedom is the key to prosperity.

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Philippine Competitiveness: Marginal Improvements, More Required

From World Economic Forum (bold emphasis mine)

Up 10 places to 75th, the Philippines posts one of the largest improvements in this year’s rankings. The vast majority of individual indicators composing the GCI improve, sometimes markedly. Yet the challenges are many, especially in the areas at the foundation of any competitive economy, even at an early stage of development.

The quality of the country’s public institutions continues to be assessed as poor: the Philippines ranks beyond the 100 mark on each of the 16 related indicators. Issues of corruption and physical security appear particularly acute (127th and 117th, respectively). The state of its infrastructure is improving marginally, but not nearly fast enough to meet the needs of the business sector. The country ranks a mediocre 113th for the overall state of its infrastructure, with particularly low marks for the quality of its seaport (123rd) and airport infrastructure (115th). Finally, despite an enrolment rate of around 90 percent, primary education is characterized by low-quality standards (110th). Against such weaknesses, the macroeconomic situation of the Philippines is more positive: the country is up 14 places to 54th in the macroeconomic environment pillar, thanks to slightly lower public deficit and debt, an improved country credit rating, and inflation that remains under control.

In the other, more complex pillars of the Index, the Philippines continues to have a vast opportunity for improvement. In particular, the largely inflexible and inefficient labor market (113th) has shown very little progress over the past four years. On a more positive note, the country ranks a good 57th in the business sophistication category, thanks to a large quantity of local suppliers, the existence of numerous and well developed clusters, and an increased presence of Filipino businesses in the higher segments of the value chain. Finally, the sheer size of the domestic market (36th) confers a notable competitive advantage.

I would suggest that much of the aforementioned improvements may have been due to macro economic trends more than having been policy induced.

That said, the Philippines needs more economic freedom and less reliance on politics to improve trade competitiveness

Wednesday, June 01, 2011

How Anti-Dumping Leads to Reduced Competitiveness

For the left, because trade is a zero sum game and an activity done by nations and not by individuals, imbalances are always someone’s fault. Thus prescribe policies that lean towards protectionism.

One of their populist claim is that asymmetric currency values leads to the alleged imbalances. But they hardly talk about how extant protectionist policies have been contributing to the loss of competitiveness and consequently high unemployment rates.

One of such protectionist policy is the anti-dumping emasures

Cato’s Dan Ikenson elaborates (bold highlights mine)

During the decade from January 2000 through December 2009, the U.S. government imposed 164 antidumping measures on a variety of products from dozens of countries. A total of 130 of those 164 measures restricted (and in most cases, still restrict) imports of intermediate goods and raw materials used by downstream U.S. producers in the production of their final products. Those restrictions raise the costs of production for the downstream firms, weakening their capacity to compete with foreign producers in the United States and abroad.

In all of those cases, trade-restricting antidumping measures were imposed without any of the downstream companies first having been afforded opportunities to demonstrate the likely adverse impact on their own business operations. This is by design. The antidumping statute forbids the administering authorities from considering the impact of prospective duties on consuming industries—or on the economy more broadly—when weighing whether or not to impose duties.

That asymmetry has always been insane, but given the emergence and proliferation of transnational production and supply chains and cross-border investment (i.e., globalization)—evidenced by the fact that 55% of all U.S. import value consists of raw materials, intermediate goods, and capital equipment (the purchases of U.S. producers)—it is now nothing short of self-flagellation.

Most of those import-consuming, downstream producers—those domestic victims of the U.S. antidumping law—are also struggling U.S. exporters. In fact those downstream companies are much more likely to export and create new jobs than are the firms that turn to the antidumping law to restrict trade. Antidumping duties on magnesium, polyvinyl chloride, and hot-rolled steel, for example, may please upstream, petitioning domestic producers, who can subsequently raise their prices and reap greater profits. But those same “protective” duties are extremely costly to U.S. producers of auto parts, paint, and appliances, who require those inputs for their own manufacturing processes.

Read the rest here

Monday, March 07, 2011

Why Global Labor Unions Have Been On A Decline

Labor unions have been on a declining trend, not just locally but internationally.

Trade or Labor Unions, according to the Wikipedia, is “organisation of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members (rank and file members) and negotiates labour contracts (collective bargaining) with employers. This may include the negotiation of wages, work rules, complaint procedures, rules governing hiring, firing and promotion of workers, benefits, workplace safety and policies. The agreements negotiated by the union leaders are binding on the rank and file members and the employer and in some cases on other non-member workers.”

Labor unions, for me, function as political force, which uses government laws for extracting economic privileges, at the expense of the company owners, non-labor union workers and taxpayers indirectly (such as the GM bailout) or directly (government unions).

The main goal of the labor union is to restrict manpower supply and to raise wages and benefits above market levels. And in doing so, labor unions add to the imbalances in the labor markets, which results to higher unemployment levels and the lack of competitiveness among many others.

For public unions the desire is for more taxpayer funded privileges.

In other words, labor unions thrive on a non-competitive environment.

As shown in the above (interactive) chart by the New York Times, since the 1980s labor or trade union around the world has seen a sharp decline except for a few, e.g. Iceland.

The main reason: rising international competitiveness or globalization.

Cato’s Dan Griswold explains (bold highlights mine)

Economic theory offers a number of reasons why growing international competition would be damaging to the interests of labor unions. More competition in product markets means greater elasticity of demand for labor—that is, global competition means that demand for labor is more sensitive to any change in wages.

Employers competing in global markets cannot simply pass higher wage costs along to consumers in the form of higher prices because consumers themselves can choose to buy substitute products from lower-cost, often nonunionized producers.

Expanding capital mobility means that employers are more able to shift production to lower-wage countries if necessary. A more mobile company is better able to threaten or employ an “exit” option in response to union demands. In the face of product competition and capital mobility, union demands for higher wages can lead instead to fewer domestic union jobs, as has been the case in a number of firms and industries.

In contrast, in markets insulated from robust competition, unions can more readily demand a share of a company’s or industry’s profits without fear of compromising the survival or competitiveness of the employer. Insulated markets create rents in the form of abovemarket profits that unions can then bargain with management to divide between them at the expense of the consuming public.

In short, the more a country is open to trade, the bigger likelihood of the diminished role of labor unions.

There are other non trade factors are involved too.

They include, adds Mr. Griswold, more rapid growth of certain categories of workers, such as women, southerners, and white-collar workers, who are less favourable to unionization; the deregulation of transportation industries; declining efforts of unions to organize new members; government activity that substitutes for union services, such as unemployment insurance, industrial accident insurance, leave policies, and other workplace regulations; the decline in pro-union attitudes among workers; and increased resistance among employers

For me, another very critical factor second to globalization has been the ongoing transition from industrial era to the information age.

Labor unions had basically been tailored for vertical organizational structures. But times are changing. As technology (via the web) becomes more entrenched, the nature of work has gradually been reconfiguring. And this provides lesser opportunity for unionization to take place, aside from the financial incentive or viability to maintain one.

As Alvin Toffler writes in Revolutionary Wealth,

Work is increasingly mobile, taking place on airplanes, in cars, at hotels and restaurants. Instead of staying in one organization, with the same co-workers for years, individuals are moving from project team to task force and work group continually losing and gaining teammates. Many are ‘free agents’ on contract, rather than employees as such. Yet while corporations are changing at a hundred miles per hour, American unions remain frozen in amber, saddle with the legacy organizations, methods and models left over from the 1930s and the mass production era.

In other words, digitalization, automation, robotics and other technology enhancements which raises productivity are taking many people out of the industrial era work. The more outsourcing and specialization takes place the lesser role played by the labor unions.

Investing guru Doug Casey also sees the same,

The good news, however, is that coercive unions are on the way out. They're anachronisms. They're leftovers from the time when people were like interchangeable parts in the giant factories they worked in. People were so replaceable that one person was little better or worse than another – because they were basically biological robots. In the early industrial era, labor was in over-supply, society was poor, and conditions were harsh everywhere. It's understandable why workers felt they had to band together for self-protection. But the industrial era is gone. The assembly line with thousands of workers is totally outmoded. In the global information age, trying to extort high wages for manual labor is pointless. Soon robots will be doing almost everything, then nanomachines will replace the robots. People will only be doing work that requires thought, judgment, and individuality. Those aren't things that can be unionized.

It pays to look at the big picture.

Labor union trends worldwide have not been declining because of culture or politics, but because of economics.