Homeschooled students tend to achieve a high degree of academic success in college, and often outperform their peers, argue several administrators from faithful Catholic colleges recommended in The Newman Guide.The experience of these administrators with homeschooled students correlates with a 2013 study—conducted for the Journal of Catholic Education—which found significant evidence of higher ACT and SAT scores and overall GPAs for homeschooled students who attend a Catholic university. Marc Snyder, assistant head of school for students at Rhodora J. Donahue Academy in Florida, conducted the study by surveying students attending Ave Maria University.The study’s sample population was composed of 33.6 percent homeschooled students, 34.8 percent Catholic high school students, and 31.6 percent public high school students. It found “a positive and significant difference between homeschooled students and public schooled students.” Homeschooled students apparently “outperformed traditionally schooled students on two of four measures,” indicating “that homeschooled students are academically valuable to the university,” according to Notre Dame’s Cardus Religious Schools Initiative.“Homeschooled students are invariably among our better students, and as more enroll, experience continues to confirm this,” said Dr. David Williams, interim vice president for academic affairs and associate professor of theology at Belmont Abbey College in Belmont, N.C., in an interview with The Cardinal Newman Society. “The average range of ability tends to be higher among homeschooled students who study at [Belmont] and compares well with the very best of public and privately-schooled students.”“We’re always pleased with our homeschooled students,” Williams told the Society. “Not only do they tend to be among the best academically, but they also possess a great deal of initiative and eagerness to participate in the college community.”

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Friday, February 20, 2015

US Catholic Colleges say Homeschoolers do Better

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Quote of the Day: The Necessary is Not to be Confused with the Causal

A drivers license is something binary: Pass/Fail. Nobody is foolish enough to try to get high scores in it to improve his CV with a "drivers license from the prestigious center X, summa cum laude". We understand the nonlinearity there; and we get the point that failing the test makes one a bad driver on the road, but better grades at the test won't necessarily make one a better driver. It is an entirely via negativa statement; failing (the negative) is where the information resides, where school knowledge may map to reality. The necessary is not to be confused with the causal.Now try to translate the idea into other areas of education. The statement "failing to get a degree is bad for you" does not necessarily mean that "better grades are good". It may even mean that higher grades might indicate a sick mind. This is the difference between SATISFICING and OPTIMIZING. An ecologically calibrated person, aware of the fuzziness of the mapping betwen education and skills, should be able to aim for just pass, and not be penalized by the nerd wasting time on fitting his brain cells to the exam at the expense of other skills and activities, such as street fights, reading Montaigne, or meditating under a tree. Given that university knowledge does not map to true knowledge, to protect people from themselves, university degrees should never be anything but binary, without the fluff "honors, shmonors", etc.

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Education: The Difference Between Learning How to Think and What to Think

Education is an ongoing confrontation between those who want to help children learn how to think, and those who want to teach them what to think. While there are numerous variations on these themes, the contrast can most clearly be found in the distinctions between child-centered Montessori systems, and teacher- and test-centered schools. Government schools usually fall into the latter category. Homeschooling, religious schools, un-schooling, and other forms tend to emphasize either the "how" or the "what" in their efforts with children.Those who focus on learning how to think have in mind helping children develop their own methods of questioning and analyzing the world around them; to control their own inquiries and opinions; to the end of helping children become independent, self-directed persons. The role of the teacher in such a setting is to provide new learning situations (e.g., open up new subjects of inquiry when the student is ready to do so) and to facilitate the processes of questioning so as to help the students get to deeper levels of understanding.People who have developed the capacity for epistemological independence are not easy to control for purposes that do not serve their interests. Institutions – which have purposes of their own that transcend those of individuals – require a mass-minded population that has been conditioned to accept outer-imposed definitions of "reality." Any deviation from this systemic purpose – as would derive from students questioning how the arrangement would benefit them – would be fatal to all forms of institutionalism.The established order has, from one culture and time period to another, insisted on educational systems that train young minds into what to think. "Truth" becomes a set of beliefs that conform to an institutional imperative, and it becomes the purpose of schools to inculcate such a mindset. Whereas "how to think" learning that finds its purpose and focus within the minds of self-directed, independent students, "what to think" education derives from outside the students’ experiences and analytical skills. As Ivan Illich so perceptively expressed it, "[s]chool is the advertising agency which makes you believe that you need the society as it is."To this end, the established order has helped generate – with eager assistance from academia – a belief that all understanding is a quality requiring phalanxes of self-styled "experts" who, by virtue of their prescribed status, enjoy monopolies to offer opinions about their respective fields of study. Plato’s designation of "philosopher kings" has been sub-franchised into categories of "experts" to be found in "history," "physics," "psychology," "economics," "law," and seemingly endless sub-groupings that negate the role once respected for those who had received a "liberal arts" education.

Friday, March 09, 2012

When College Education Isn’t Sufficient

Work place education matters more than a college degree, so argues Professor Alex Tabarrok at the Chronicle Review (hat tip Prof Mark Perry; bold emphasis mine)

The obsessive focus on a college degree has served neither taxpayers nor students well. Only 35 percent of students starting a four-year degree program will graduate within four years, and less than 60 percent will graduate within six years. Students who haven't graduated within six years probably never will. The U.S. college dropout rate is about 40 percent, the highest college dropout rate in the industrialized world. That's a lot of wasted resources. Students with two years of college education may get something for those two years, but it's less than half of the wage gains from completing a four-year degree. No degree, few skills, and a lot of debt is not an ideal way to begin a career.

College dropouts are telling us that college is not for everyone. Neither is high school. In the 21st century, an astounding 25 percent of American men do not graduate from high school. A big part of the problem is that the United States has paved a single road to knowledge, the road through the classroom. "Sit down, stay quiet, and absorb. Do this for 12 to 16 years," we tell the students, "and all will be well." Lots of students, however, crash before they reach the end of the road. Who can blame them? Sit-down learning is not for everyone, perhaps not even for most people. There are many roads to an education.

Consider those offered in Europe. In Germany, 97 percent of students graduate from high school, but only a third of these students go on to college. In the United States, we graduate fewer students from high school, but nearly two-thirds of those we graduate go to college. So are German students poorly educated? Not at all.

Instead of college, German students enter training and apprenticeship programs—many of which begin during high school. By the time they finish, they have had a far better practical education than most American students—equivalent to an American technical degree—and, as a result, they have an easier time entering the work force. Similarly, in Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, and Switzerland, between 40 to 70 percent of students opt for an educational program that combines classroom and workplace learning.

In the United States, "vocational" programs are often thought of as programs for at-risk students, but that's because they are taught in high schools with little connection to real workplaces. European programs are typically rigorous because the training is paid for by employers who consider apprentices an important part of their current and future work force. Apprentices are therefore given high-skill technical training that combines theory with practice—and the students are paid! Moreover, instead of isolating teenagers in their own counterculture, apprentice programs introduce teenagers to the adult world and the skills, attitudes, and practices that make for a successful career.

Elites frown upon apprenticeship programs because they think college is the way to create a "well-rounded citizenry." So take a look at the students in Finland, Sweden, or Germany. Are they not "well rounded"? The argument that college creates a well-rounded citizen can be sustained only by defining well rounded in a narrow way. Is someone who can quote from the school of Zen well rounded? Only if they can also maintain a motorcycle. Well-roundedness comes not from sitting in a classroom but from experiencing the larger world.

The focus on college education has distracted government and students from apprenticeship opportunities. Why should a major in English literature be subsidized with room and board on a beautiful campus with Olympic-size swimming pools and state-of-the-art athletic facilities when apprentices in nursing, electrical work, and new high-tech fields like mechatronics are typically unsubsidized (or less subsidized)? College students even get discounts at the movie theater; when was the last time you saw a discount for an electrical apprentice?

Our obsessive focus on college schooling has blinded us to basic truths. College is a place, not a magic formula. It matters what subjects students study, and subsidies should focus on the subjects that matter the most—not to the students but to everyone else. The high-school and college dropouts are also telling us something important: We need to provide opportunities for all types of learners, not just classroom learners. Going to college is neither necessary nor sufficient to be well educated. Apprentices in Europe are well educated but not college schooled. We need to open more roads to education so that more students can reach their desired destination.

College education has been designed for the industrial age or the mass production political economy.

The deepening of the information age, marked by the increasing transition towards niche markets, will lead to leaner but highly specialized business processes that will be reflected on the evolving dynamics of organizational structures.

Job requirements will thus be driven by specialization. And meeting these would translate a change in the delivery medium of educational content, which are likely to move away from classroom models towards personalized education (such as P2P collaborative tutoring, and many other online models) or the demassification of education.

And in this regards Mr. Tabarrok’s observation of education derived from apprenticeship/vocational/technical degree or workplace education will be magnified.

It is also important to point out that taxpayer spending on current public educational programs will become increasingly irrelevant.

Monday, October 24, 2011

Higher Education in the Information Age

How higher education may look like in the future

From Mark Weedman (hat tip Professor Arnold Kling)

A school in this Google model derives its identity from its faculty and curriculum, or its “software” while de-emphasizing the importance of its infrastructure, such as its classroom, library and other campus facilities. In other words, it is possible to provide a first-class education in a school without a full range of campus facilities (or maybe even a school without a traditional campus) as long as the curriculum gives students access to the right kind of critical thinking, formation and training. It used to be that to provide a first-class education required institutions to assemble all three components: faculty, library and classrooms. The Google model suggests that it is possible to re-conceive that structure entirely by shifting the focus to curriculum (and the necessary faculty to teach it) and then adapting whatever “hardware” is available to give the curriculum a platform.

The key to this model is the curriculum. There are a number of reasons why traditional higher education institutions have gotten away with fairly generic curricula (i.e., a series of courses taught in classrooms via lectures and discussion), but one of the most important is that the other components offset the inadequacies of curriculum. Stripping away the infrastructure exposes the curriculum and demands that it be effective and have integrity on its own. Stripping away the infrastructure, however, also frees the curriculum to provide new and dynamic ways of learning. If you have a classroom or library, you have to use it. If you do not have a classroom, then entirely new educational opportunities present themselves.

The information age will transform the way we live.

Friday, June 24, 2011

Central Planning in Education Fails

Central planning even in education doesn’t work. Take a look at Japan’s PhD’s experience

From Nature.com (hat tip: Prof Arnold Kling) [bold emphasis mine]

Of all the countries in which to graduate with a science PhD, Japan is arguably one of the worst. In the 1990s, the government set a policy to triple the number of postdocs to 10,000, and stepped up PhD recruitment to meet that goal. The policy was meant to bring Japan’s science capacity up to match that of the West — but is now much criticized because, although it quickly succeeded, it gave little thought to where all those postdocs were going to end up.

Academia doesn’t want them: the number of 18-year-olds entering higher education has been dropping, so universities don’t need the staff. Neither does Japanese industry, which has traditionally preferred young, fresh bachelor’s graduates who can be trained on the job. The science and education ministry couldn’t even sell them off when, in 2009, it started offering companies around ¥4 million (US$47,000) each to take on some of the country’s 18,000 unemployed postdoctoral students (one of several initiatives that have been introduced to improve the situation). “It’s just hard to find a match” between postdoc and company, says Koichi Kitazawa, the head of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

This means there are few jobs for the current

crop of PhDs. Of the 1,350 people awarded doctorates in natural sciences in 2010, just over half (746) had full-time posts lined up by the time they graduated. But only 162 were in the academic sciences or technological services,; of the rest, 250 took industry positions, 256 went into education and 38 got government jobs.

In short, even PhD graduates end up jobless.

The basic problem is that educational output does not conform with the desires or requirements of the marketplace.

Instead government policies, out of political goals “to match the capacity of the West”, produced surpluses, which has led to these unemployed “experts”. In other words, these unemployed PhDs had been products of misdirected political imperatives. This also applies to capital too.

It’s the same with public education. Four out of TEN college graduates in the Philippines have been unemployed. That’s because the problem hasn’t been about the lack of education, but rather, the lack of economic opportunities and the misguidance brought about by too much government interventionism.

Graduates can only work when there are available jobs. And economically productive jobs emanate from the private sector. Even government jobs are financed by taxes from the private sector. When the private sector are burdened by too much regulations, political mandates, taxes and compliance costs, investment opportunities dwindles. Thus, the surge in unemployment.

Bottom line: Education does not guarantee jobs. Economic freedom does.

Friday, June 17, 2011

US Economy: Manufacturing and Technology as Sunshine Industries?

Perhaps enrollment trends could serve as an indicator or clue on how the US economy (and perhaps the world economy) will take shape.

According to the Wall Street Journal,

Harvard Business School's incoming class will have a substantially smaller percentage of finance professionals than in previous years. Instead, a higher number of students will have manufacturing and technology backgrounds.

According to preliminary figures from Harvard's admissions department, about 25% of the 919 students in the class of 2013 are from finance industries— including private equity, banking and venture capital—compared with 32% last year.

Harvard administrators say the change reflects a greater quantity of strong applicants from nonfinance industries. The number of applicants from the finance world decreased as recession woes eased, as well.

Students with manufacturing backgrounds make up 14% of the class of 2013, up from 9% the previous year. Technology rose three percentage points to 9%.

Professor Arnold Kling calls it the Patterns of Sustainable Specialization and Trade [PSST] or the process where markets continually work to discover on where consumer demands are or the new patterns of trade.

Harvard’s incoming MBA class shows manufacturing as having the greatest growth followed by technology.

Could this signal that the new patterns of trade will become more apparent in the US manufacturing and technology industries? Will these two industries signify as the sunshine industries? (hat tip Mark Perry)

Saturday, May 07, 2011

Common Sense Education

Another treasure from marketing guru Seth Godin; this time he talks about the basic things we need to learn about: (bold highlights mine)

-How to focus intently on a problem until it's solved.

-The benefit of postponing short-term satisfaction in exchange for long-term success.

-How to read critically.

-The power of being able to lead groups of peers without receiving clear delegated authority.

-An understanding of the extraordinary power of the scientific method, in just about any situation or endeavor.

-How to persuasively present ideas in multiple forms, especially in writing and before a group.

-Project management. Self-management and the management of ideas, projects and people.

-Personal finance. Understanding the truth about money and debt and leverage.

-An insatiable desire (and the ability) to learn more. Forever.

-Most of all, the self-reliance that comes from understanding that relentless hard work can be applied to solve problems worth solving.

In short, common sense education.

We don’t need extended years for these.

Thursday, August 19, 2010

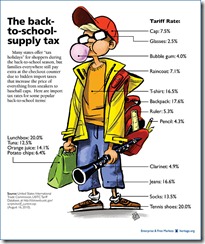

Cartoon of the Day: Tax on Education

The following enlightening caricature from Heritage Foundation underscores how taxes impact the cost of education.

I just hope that there would be a Philippine version for this.

Saturday, July 03, 2010

Wealth Makes Health And Intelligence

.bmp)

.bmp)