``But innovation, in Schumpeter’s famous phrase, is also “creative destruction”. It makes obsolete yesterday’s capital equipment and capital investment. The more the economy progresses, the more capital formation will it therefore need. Thus, the classical economist-or the accountant or the stock exchange-considers “profit” is a genuine cost, the cost of staying in business, the cost of a future in which nothing is predictable except that today’s profitable business will become tomorrow’s white elephant.”- Peter F. Drucker, Profit’s Function, The Daily Drucker.

We read from creditwritedowns.com that Morgan Stanley Asia Chairman Stephen Roach made some predictions, namely:

1 “Asia will have a less acute impact from the global financial and economic crisis”

2. “Export-led regions are followers, not leaders.” Hence would recover after their main export markets, the US and Europe, recovered.

3. “The only possibility (to recover earlier) is China, as it has large infrastructure spending in place that could provide support for economic growth.”

Dr. Roach has been one of the unassuming well respected contrarian voices, whom I have followed, who sternly warned of this crisis.

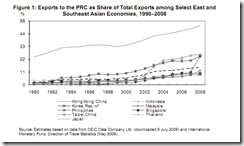

Nonetheless while we agree with some of his prognosis, where we depart with Dr. Roach is on the aspect of a ‘belated recovery’ of Asia because of its “export dependence” on US and Europe.

Creative Destruction: The Telephone Destroyed The Telegraph

While it is true that the Asian model had functioned as an export-led region over the past years, our favorite cliché, ``Past performance does not guarantee future results” would possibly come into play in the transformation of the playing field.

Let us simplify, if a business paradigm doesn’t work do you insist on pursuing the same model or do you attempt a shift?

Marketing Guru Seth Godin has a terse but poignant depiction of “solving a different problem” response to our question. We quote the terrific guru Mr. Godin,

``The telephone destroyed the telegraph.

``Here's why people liked the telegraph: It was universal, inexpensive, asynchronous and it left a paper trail.

``The telephone offered not one of these four attributes. It was far from universal, and if someone didn't have a phone, you couldn't call them. It was expensive, even before someone called you. It was synchronous--if you weren't home, no call got made. And of course, there was no paper trail.

``If the telephone guys had set out to make something that did what the telegraph does, but better, they probably would have failed. Instead, they solved a different problem, in such an overwhelmingly useful way that they eliminated the feature set of the competition.” (bold highlight mine)

In short, we see human action basically at work. To quote Ludwig von Mises, ``Action is an attempt to substitute a more satisfactory state of affairs for a less satisfactory one. We call such a willfully induced alteration an exchange.”

People who relied on old models didn’t see this coming. They would have resisted until they were overwhelmed.

The fact is the telephone replaced an entrenched system. Joseph Schumpeter, in economic vernacular coined this as “creative destruction”. And creative destruction essentially leads to new operating environments: the rise of the telephone.

Similarly, the Asian export model has been built upon the US credit bubble structure. That bubble is presently deflating and would most possibly dissipate. So is it with Europe’s model.

In other words, the global economy’s trade and investment framework will probably reconfigure based on the present operating economic realities. Countries and regions would probably operate under a set of redefined roles.

Here are three clues of the possible creative destruction transformation.

Deepening Regionalism

Figure 3: ADB: Emerging Asian Regionalism

Figure 3: ADB: Emerging Asian RegionalismThis from the ADB’s Emerging Asian Regionalism, ``In large part due to the growth of production networks just discussed, trade within Asia has increased from 37% of its total trade in 1986 to 52% in 2006 (Figure 3.3). The share of trade with Europe has risen somewhat, while that with the US and the rest of the world has fallen. As set out in Chapter 2, Asia’s intraregional trade share is now midway between Europe’s and North America’s. It is also higher than Europe’s was at the outset of its integration process in the early 1960s.

``But trade has not been diverted from the rest of the world. On the contrary, trade with each of Asia’s four main partner groups has increased in the last two decades—not just absolutely, but also relative to Asia’s GDP (Figure 3.4). For example, Asia’s trade with the EU has more than doubled as a share of its GDP, from 2.6% in 1986 to 6.0% in 2006. The increase is even larger as a share of the EU’s GDP. The aggregate trade data thus suggests that Asia is steadily integrating both regionally and globally.”

The fact is that Asia has steadily been regionalizing or developing its intraregional dynamics even when the bubble structure had been functional. Today’s imploding bubble isn’t likely to alter such deepening trend.

Moreover, the current unwinding bubble structure is emblematic of a discoordination process from a ‘market clearing’ environment.

Under this phase, spare capacities are being shut or sold, excess labor are being laid off, surplus inventories are being liquidated and losses are being realized. Essentially new players are taking over the affected industries. And new players will be coming in with fresh capital to replace those whom have lost. Fresh capital will come from those economies with large savings or unimpaired banking system (see Will Deglobalization Lead To Decoupling?)

And like any economic cycles, this adjustment process will lead to equilibrium. Eventually a trough will be reached, where demand and supply should balance out and a transition to recovery follows.

The post bubble structure is likely to reinforce and not reduce this intraregional dynamic.

So in contrast to the notion of a belated recovery in Asia hinged on the old decrepit model, a China recovery should lift the rest of Asia out of the doldrums.

Asia and not the old stewards should lead the recovery based on the new paradigm.

And in every new bullmarket there always has been a change in market leadership. We are probably witnessing the incipience of such change today.

Real Savings Function As Basic Consumption

The assumption of the intransigence of Asia as an export led model is predicated on Keynesian theory of aggregate demand. In essence, for as long as borrowing and lending won’t recover in the traditional ‘aggregate demand’ economies, there won’t be a recovery in export led economies.

But in contrast to such consensus view, demand is not our problem, production from savings is.

According to quote Dr. Frank Shostak, ``At any point in time, the amount of goods and services available are finite. This is not so with regard to people’s demand, which tends to be unlimited. Most people want as many things as they can think of. What thwarts their demand is the availability of means. Hence, there can never be a problem with demand as such, but with the means to accommodate demand.

``Moreover, no producer is preoccupied with demand in general, but rather with the demand for his particular goods.”

``In the real world, one has to become a producer before one can demand goods and services. It is necessary to produce some useful goods that can be exchanged for other goods.”

A sole shipwrecked survivor in an island will need to scour for food and water in order to consume. This means he/she can only consume from what can be produced (catch or harvest). It goes the same in a barter economy; a baker can only have his pair of shoes if he trades his spare breads with surplus of shoes made by the shoemaker.

Surplus bread or shoes or produce, thus, constitute as real savings. And to expand production, the shoemaker, the baker or even the shipwrecked survivor would need to invest their surpluses or savings to achieve more output which enables them to spend more in the future.

Instead of getting x amounts of coconuts required for daily nourishment, the shipwrecked survivor will acquire a week’s harvest and use his spare time to make a knife so he can either make ladder (to improve output), build a boat (to catch fish or to go home) or to hunt animals (to alter diet) or to make a shelter (for convenience). Essentially savings allows the survivor to improve on his/her living conditions.

To increase production for the goal of increasing future consumption, the savings of both the shoemaker and the baker would likely be invested in new equipment (capital goods).

Again to quote Dr. Shostak (bold highlight mine), ``What limits the production growth of goods and services is the introduction of better tools and machinery (i.e., capital goods), which raises worker productivity. Tools and machinery are not readily available; they must be made. In order to make them, people must allocate consumer goods and services that will sustain those individuals engaged in the production of tools and machinery.

``This allocation of consumer goods and services is what savings is all about. Note that savings become possible once some individuals have agreed to transfer some of their present goods to individuals that are engaged in the production of tools and machinery. Obviously, they do not transfer these goods for free, but in return for a greater quantity of goods in the future. According to Mises, "Production of goods ready for consumption requires the use of capital goods, that is, of tools and of half-finished material. Capital comes into existence by saving, i.e., temporary abstention from consumption.”

``Since saving enables the production of capital goods, saving is obviously at the heart of the economic growth that raises people's living standards. On this Mises wrote, “Saving and the resulting accumulation of capital goods are at the beginning of every attempt to improve the material condition of man; they are the foundation of human civilization.”

So what changes this primitive way of production-consumption to mainstream’s consumption-production framework?

The answer is debt. Debt can be used in productive or non-productive spending. But debt today is structured based on the modern central banking.

Think credit card. Credit card allows everyone to extend present consumption patterns by charging to future income. If debt is continually spent on non-productive items, it eventually chafes on one’s capacity to pay. It consumes equity. Eventually, overindulgence in non productive debt leads bankruptcy. And this epitomizes today’s crisis.

But debt issued from real savings can’t lead to massive clustering of errors (bubble burst) because they are limited and based on production surpluses. It is non productive debt issued from ‘something out of nothing’ or the fractional banking system combined with loose monetary policies from interest manipulations that skews the lending incentives and enables massive malinvestments.

To aptly quote Mr. Peter Schiff’s analysis of today’s crisis, ``Credit, whether securitized or not, cannot be created out of thin air. It only comes into existence though savings, which must be preceded by under-consumption. Since savings are scarce, any government guarantees toward consumer credit merely crowd out credit that might otherwise have been available to business. During the previous decade too much credit was extended to consumers and not enough to producers (securitization focused almost exclusively on consumer debt). The market is trying to correct this misallocation, but government policy is standing in the way. When consumers borrow and spend, society gains nothing. When producers borrow and invest, our capital stock is improved, and we all benefit from the increased productivity.”

Now if capital comes into existence by virtue of savings, we should ask where most of the savings are located?

The answer is in Asia and emerging markets.

Figure 4: Matthews Asian Fund: Asia Insight

Figure 4: Matthews Asian Fund: Asia InsightAccording to Winnie Puah of Matthews Asia, ``The economic potential and impact of Asian savings have yet to be fully unleashed at home. Indeed, Asia’s excess savings fuelled the recent boom in U.S. consumption and housing markets. Creating a consumption boom in Asia would mean that Asia needs to borrow and spend more. To date, governments are supporting domestic demand with fiscal stimulus packages—but it is household balance sheets that hold the key to developing a consumer culture. Overall, Asian households are well-positioned to increase spending—most have low debt levels and high rates of savings… there is a noticeable divergence in saving patterns between emerging and mature economies over the past decade, particularly since Asia learned a hard lesson from being overleveraged during the Asian financial crisis. Today, most Asian households save 10%—30% of their disposable incomes. China’s households, for example, have over US$3 trillion in savings deposits but have borrowed only US$500 billion.”

Thus I wouldn’t underestimate the power of Asia’s savings that could be converted or transformed into spending.

Asia’s Tsunami of Middle Class Consumers

In my August 2008 article Decoupling Recoupling Debate As A Religion, we noted of the theory called as the “Acceleration Phenomenon” developed by French economist Aftalion, who propounded that a marginal increase in the income distribution of heavily populated countries as China, based on a Gaussian pattern, can potentially unleash a torrent of middle class consumers.

Apparently, the Economist recently published a similar but improvised version of the Acceleration Phenomenon model. And based on this, the Economist says that 57% of the world population is now living in middle class standards (see figure 5)!

Figure 5: The Economist: The Rise of the Middle Class?

Figure 5: The Economist: The Rise of the Middle Class?From The Economist (bold highlights mine), ``In practice, emerging markets may be said to have two middle classes. One consists of those who are middle class by any standard—ie, with an income between the average Brazilian and Italian. This group has the makings of a global class whose members have as much in common with each other as with the poor in their own countries. It is growing fast, but still makes up only a tenth of the developing world. You could call it the global middle class.

``The other, more numerous, group consists of those who are middle-class by the standards of the developing world but not the rich one. Some time in the past year or two, for the first time in history, they became a majority of the developing world’s population: their share of the total rose from one-third in 1990 to 49% in 2005. Call it the developing middle class.

``Using a somewhat different definition—those earning $10-100 a day, including in rich countries—an Indian economist, Surjit Bhalla, also found that the middle class’s share of the whole world’s population rose from one-third to over half (57%) between 1990 and 2006. He argues that this is the third middle-class surge since 1800. The first occurred in the 19th century with the creation of the first mass middle class in western Europe. The second, mainly in Western countries, occurred during the baby boom (1950-1980). The current, third one is happening almost entirely in emerging countries. According to Mr Bhalla’s calculations, the number of middle-class people in Asia has overtaken the number in the West for the first time since 1700.”

So apparently, today’s phenomenon seems strikingly similar to Seth Godin’s description of the creative destruction of the telegraph.

The seeds of the rising middle class appear to emanate from the wealth transfer from the developed Western economies to Asia and emerging markets. Put differently, Asia and EM economies could be the fruits from the recent ‘creative destruction’.

Some Emerging Signs?

However, there are always two sides to a coin.

For some, the present crisis signify as a potential regression of these resurgent middle class to their poverty stricken state, as the major economies slumps and drag the entire world into a vortex.

For us, substantial savings or capital (the key to consumption), deepening regionalism, underutilized or untapped credit facilities, rapidly developing financial markets, a huge middle class, unimpaired banking system, and most importantly policies dedicated to economic freedom serve as the proverbial line etched in the sand.

One might add that the negative interest rates or low interest policies and the spillage effect from stimulus programs from developed economies appear to percolate into the financial systems of Asia and emerging markets.

Although these are inherently long term trends, we sense some emergent short term signs which may corroborate this view:

1. Despite the 30% slump in the global Mergers and Acquisitions in 2008, China recorded a 44% jump to $159 billion mostly to foreign telecommunication and foreign parts makers (Korea Times). Japan M&A soared last year to a record $165 billion in 2008 a 13% increase (Bloomberg).

2. Credit environment seems to be easing substantially.

According to FinanceAsia (Bold highlights), ``The fallout from Japan's banking crisis offers clues to how the current situation may resolve itself. Back then, healing started first in the areas that had been most affected -- interbank lending recovered earliest, followed by credit markets, volatility markets and finally, many years later, equity markets.

``In today's crisis, interbank lending is already starting to recover. The spread between three-month interbank lending rates and overnight rates, which provides a key measure of the health of credit markets, has dropped significantly from its peak of 364bp in early 2008 down to less than 100bp today. As the interbank market recovers, credit should be next to heal.

``However, at the moment, triple-B spreads are at their highest levels in more than 100 years, which makes credit look like an extremely attractive investment opportunity. And there is every reason to expect that Asian corporates will participate in the healing, perhaps even as quickly as their counterparts in the US. (Oops and I thought everyone said divergence wasn’t possible or decoupling is a myth)

3. Asian companies have begun to engage in debt buyback. Again from FinanceAsia, ``Asian companies are buying back their debt with gusto and this could be a sign that credit markets are on the mend, according to Morgan Stanley.

``Asian companies are betting that credit will offer the best returns in 2009 and, like the smart traders they are, executives in the region are busy buying back their debt with gusto.

4. A picture speaks a thousand words…

Figure 6: A BRIC Decoupling?

Figure 6: A BRIC Decoupling? China and Brazil appear to be leading the BRIC recovery while India (BSE) and Russia (RTS) seem to initiating their own.

For financial markets of developed economies, don’t speak of bad words.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)