John Mauldin defines inflation as

a combination of the money supply AND the velocity of money. In short, if the velocity of money is falling, the Fed can print a great deal of money (expanding its balance sheet) without bringing about inflation.

So how valid or real is his definition?

The Velocity of M2 has been in a decline since 2006. This decline culminated in 2008 with the Lehman bankruptcy. Since bottoming out in early 2009, the velocity of M2 has been rangebound

In contrast, % change of M2 has been ascendant from 2007 and peaked during the first quarter of 2009. From 2009-2010, M2 has been in a steady decline. Following a bottom in early 2010, the % change of the M2 has been roaring upwards.

By the conditional definition that inflation is a function of Money Supply AND velocity, the US should be witnessing disinflation from 2009-2010, since it was only then where both money stock AND velocity had a synchronized decline. And from 2010 to date, a stagnant or rangebound inflation rate.

Unfortunately, only part of the story seems correct. US inflation rate fell from July 2008 and bottomed in July 2009. Since, US CPI rate continues to climb upwards in defiance of Mr. Mauldin’s definition of inflation (chart from trading economics)

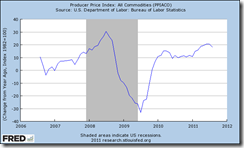

The same story applies when seen with the US Producer’s Price Index

Mr. Mauldin was actually discussing the chances of hyperinflation in the US using the Weimar Germany as example

The Weimar hyperinflation according to Wikipedia.org is the

period of hyperinflation in Germany (the Weimar Republic) between 1921 and 1923. (I am emphasizing the period)

Chart from Now and Futures

During the Weimar episode, the velocity of money

In short, in the Weimar experience velocity of money lagged money supply growth.

Professor Hans Sennholz described how hyperinflation occurred in Weimar Germany (bold emphasis mine)

The German inflation of 1914–1923 had an inconspicuous beginning, a creeping rate of one to two percent. On the first day of the war, the German Reichsbank, like the other central banks of the belligerent powers, suspended redeemability of its notes in order to prevent a run on its gold reserves.

Like all the other banks, it offered assistance to the central government in financing the war effort. Since taxes are always unpopular, the German government preferred to borrow the needed amounts of money rather than raise its taxes substantially. To this end it was readily assisted by the Reichsbank, which discounted most treasury obligations.

A growing percentage of government debt thus found its way into the vaults of the central bank and an equivalent amount of printing press money into people's cash holdings. In short, the central bank was monetizing the growing government debt.

By the end of the war the amount of money in circulation had risen fourfold and prices some 140 percent. Yet the German mark had suffered no more than the British pound, was somewhat weaker than the American dollar but stronger than the French franc. Five years later, in December 1923, the Reichsbank had issued 496.5 quintillion marks, each of which had fallen to one-trillionth of its 1914 gold value

I am delighted that the recent political schisms (Volker et. al.) and the division among US Federal Reserve officials seems to have prompted team Bernanke’s reluctance to deploy QE 3.0.

This is a manifestation of institutional ‘check and balance’ that indeed lessens the odds of a US based hyperinflation

However, using velocity of money as an excuse to justify the actions of the US Federal Reserve resonates exactly why hyperinflation transpired in Weimar

Again Hans Sennholz (bold emphasis added)

The most amazing economic sophism that was advanced by eminent financiers, politicians, and economists endeavored to show that there was neither monetary nor credit inflation in Germany. These experts readily admitted that the nominal amount of paper money issued was indeed enormous. But the real value of all currency in circulation, that is, the gold value in terms of gold or goods prices, they argued, was much lower than before the war or than that of other industrial countries….

Of course, this fantastic conclusion drawn by monetary authorities and experts bore ominous consequences for millions of people. Through devious sophisms it simply removed the cause of disaster from individual responsibility and thus also all limits to the issuance of more paper money.

The source of this momentous error probably lies in the ignorance of one of the most important determinants of money value, which is the very attitude of people toward money. For one reason or another people may vary their cash holdings. An increase in cash holdings by many people tends to raise the exchange value of money; reduction in cash holdings tends to lower it. Now in order to change radically their cash holdings, individuals must have cogent reasons. They naturally enlarge their holdings whenever they anticipate rising money value as, for instance, in a depression. And they reduce their holdings whenever they expect declining money value. In the German hyperinflation they reduced their holdings to an absolute minimum and finally avoided any possession at all. It is obvious that goods prices must then rise faster and the value of money depreciate faster than the rate of money creation. If the value of individual cash holdings declines faster than the rate of money printing, the value of the total stock of money must also depreciate faster than this rate. This is so well understood that even the mathematical economists emphasize the money "velocity" in their equations and calculations of money value. But the German monetary authorities were unaware of such basic principles of human action.

To give an aura of credibility, many adhere to statistical aggregates for economic definitions and explanations. They forget that economics and money is about people and their actions.

1 comment:

Sorry dude. This is a very crude view of inflation. A good deal of the post-2008 inflation was driven by rising commodity prices. This is common knowledge. Your analysis falls apart because you haven't actually checked what the central banks say is causing the inflation -- which would have been the first step in any decent analysis.

Inflation is not a simple issue of a rising money supply. It never has been. Weimar, for example, was largely due to capacity destruction and foreign exchange purchases to repay war debt.

And no, QE is not going to cause hyperinflation. So, dump the T-bill shorts before you lose the rest of your money.

Post a Comment