``For inflation does not come without cause. It is the result of policy. It is the result of something that is always within the control of government—the supply of money and bank credit. An inflation is initiated or continued in the belief that it will benefit debtors at the expense of creditors, or exporters at the expense of importers, or workers at the expense of employers, or farmers at the expense of city dwellers, or the old at the expense of the young, or this generation at the expense of the next. But what is certain is that everybody cannot get rich at the expense of everybody else. There is no magic in paper money.” -Henry Hazlitt, What You Should Know About Inflation p.135

Ever since the US Federal Reserve announced that it would embark on buying $300 billion of long term US treasury bonds and ante up on its acquisitions of mortgage-based securities by $750 billion, this has generated an electrifying response in the global financial markets.

First, it hastened the decline in the US dollar index, see figure 1.

Figure 1: stockcharts.com: Transmission Impact of the US Fed’s QE via the US dollar

Figure 1: stockcharts.com: Transmission Impact of the US Fed’s QE via the US dollar

Next, it goosed up both the commodity markets (as represented by the CRB-Reuters benchmark lowest pane) and key global equity markets, as seen in the Dow Jones World index (topmost pane) and the Dow Jones Asia ex-Japan (pane below main window). The seemingly congruous movements seem to be in response to US dollar’s activities.

At the end of the week as the US dollar rallied vigorously, where the same assets reacted in the opposite direction. So it is our supposition that correlation here implies causation: a falling US dollar simply means more surplus dollars in the global financial system relative to its major trading partners.

In other words, since the efficiency of the global financial markets have greatly been impeded by collaborative intensive worldwide government interventions, the main vent of the officially instituted policy measures have been through the currency markets.

And since the US dollar is the world’s de facto currency reserve, the actions of the US dollar are thereby being transmitted into global financial assets. As former US Treasury secretary John B. Connolly memorably remarked in 1971, ``The US dollar is our currency, but your problem!”

Bernanke’s Inflation Guidebook

And as we have long predicted, the US Federal Reserve will be using up its policy arsenal tools to the hilt. And if there is anything likeable from Mr. Bernanke is that his prospective policy directives have been explicitly defined in his November 21 2002 speech Deflation: Making Sure It Doesn’t Happen Here which has served as a potent guidebook for any Central Bank watcher.

For instance, the latest move to prop up the long end of the Treasury market was revealed in 2001 where Bernanke noted that ``a sufficiently determined Fed can peg or cap Treasury bond prices and yields at other than the shortest maturities”, and the shoring up of the mortgage market as ``might next consider attempting to influence directly the yields on privately issued securities”.

Nevertheless even as Mr. Bernanke once said that ``I am today neither forecasting nor recommending any attempt by U.S. policymakers to target the international value of the dollar”, he believes in the ultimate antidote against the threat of deflation could be through the transmission effects of the US dollar’s devaluation, ``it's worth noting that there have been times when exchange rate policy has been an effective weapon against deflation” where he has showcased the great depression as an example; he said,`` If nothing else, the episode illustrates that monetary actions can have powerful effects on the economy, even when the nominal interest rate is at or near zero, as was the case at the time of Roosevelt's devaluation.”

Of course, this isn’t merely going to be a central bank operation but one combined with coordinated efforts with the executive department or through the US Treasury, again Mr. Bernanke, ``effectiveness of anti-deflation policy could be significantly enhanced by cooperation between the monetary and fiscal authorities”.

Although Mr. Bernanke’s main prescription has been a tax cut, he combines this with government spending via purchases of assets, he recommended `` the government could increase spending on current goods and services or even acquire existing real or financial assets. If the Treasury issued debt to purchase private assets and the Fed then purchased an equal amount of Treasury debt with newly created money, the whole operation would be the economic equivalent of direct open-market operations in private assets.”

And the recent fiscal stimulus, guarantees and other bailout programs which have amassed to some nearly $9.9 trillion [see $9.9 Trillion and Counting, Accelerating the Mises Moment] of US taxpayers exposure plus the recent $1 trillion Private Investment Program or PPIP have all accrued in accordance to Mr. Bernanke’s design.

In all, Mr. Bernanke hasn’t been doing differently from Zimbabwe’s Dr. Gideon Gono except that the US Federal Reserve can deliver the same results via different vehicles.

Inflation is what policymakers have been aspiring for and outsized inflation is what we’re gonna get.

Stages of Inflation

There are many skeptics that remain steadfast to the global deflationary outlook based on either the continued worsening outlook of debt deleveraging in the major financial institutions and or from the premise of excessive supplies or surplus capacities in the economic system.

We agree with the debt deflation premise (but not the global deflationary environment) and pointed to the dim prospects of Geither’s PPIP program [see Why Geither's Toxic Asset Program Won't Float] precisely from the angle of deleveraging and economic recessionary pressures. However, this is exactly why central bankers will continue to massively inflate-to reduce the real value of these outstanding obligations. And this episode has been a colossal tug-of-war between government generated inflation and market based deflation.

It is further a curiosity how the academe world or mainstream analysis has been obsessing over the premise of the normalization of “borrowing and lending” in order to spur inflation. It just depicts how detached “classroom” or “ivory tower” based thinking is relative to the “real” functioning world.

We don’t really need to restore the private sector driven credit process to achieve inflation. As manifested in the recent hyperinflation case of Zimbabwe; all that is needed is for a government to simply endlessly print money and to spend it.

The sheer magnitude of money printing combined with market distortive administrative policies sent Zimbabwe’s inflation figures skyrocketing to vertiginous heights (89.7 SEXTILLION percent or a number backed with 21 zeroes!!!) as massive dislocations and shortages in the economy emerged out of such policy failures.

By the way, as we correctly predicted in Dr. Gideon Gono Yields! Zimbabwe Dump Domestic Currency, since the “Dollarization” or “rand-ization or pula-ization” of Zimbabwe’s economy, prices have begun to deflate (down 3% last January and February)! The BBC reported ``The Zimbabwean dollar has disappeared from the streets since it was dumped as official currency.” The evisceration of the Zimbabwean Dollar translates to equally a declension of power by the Mugabe regime which has resorted to a face saving “unity” government between the opposition represented by current Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai of the MDC and President Mugabe's Zanu-PF.

And going back to inflation basics, we might add that a dysfunctional deflation plagued private banking system wouldn’t serve as an effective deterrent to government/s staunchly fixated with conflagrating the inflation flames.

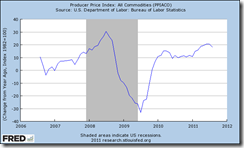

For instance, in the bedrock of the ongoing unwinding debt deleveraging distressed environment, the UK has “surprisingly” reported a resurgence of inflation last February brought about by a “rise” in food prices due to the “decline” in UK’s currency the British pound-which has dropped by some 26% against the US dollar during the past year (Bloomberg). While many astonished analysts deem this to be a “hiccup”, we believe that there will be more dumbfounding of the consensus as inflation figures come by. And we see the same “startling” rise in inflation figures reported in Canada and in South Africa.

What we are going to see isn’t “stag-deflation” but at the onset STAGFLATION, an environment which dominated against the conventional expectations during the 70s.

Why? Because this isn’t simply about demand and supply of goods and services as peddled by the orthodoxy, but about the demand and supply of money relative to the demand and supply of goods and services. Better defined by Professor John Hussman, ``Inflation basically measures the percentage change in the ratio of two “marginal utilities”: the marginal utility of real goods and services divided by the marginal utility (mostly for portfolio and transactions purposes) of government liabilities.”

For instance mainstream analysts tell us that stock prices reflect on economic growth expectations and that during economic recessions, which normally impairs earnings growth, this automatically translates to falling stock prices.

We’ll argue that it depends--on the rate of inflation.

Figure 2: Nowandfutures.com: Weimar Germany: Surging Stock Prices on Massive Recession

This is basically the same argument we’ve made based on Zimbabwe’s experience, in the Weimar hyperinflation of 1921-1923, its massively devaluing currency, which accounted for as the currency’s loss of store of value sent people searching for an alternative safehaven regardless of the economic conditions.

People piled into stocks (right), whose index gained by 9,999,900%, even as unemployment rate soared to nearly 30%! It’s because the German government printed so much money that Germans lost fate in their currency “marks” and sought refuge in stocks. Although, stock market gains were mostly nominal and while the US dollar based was muted (green line).

In other words, money isn’t neutral or that the impact of monetary inflation ranges in many ways to a society, to quote Mr. Ludwig von Mises, ``there is no constant relation between changes in the quantity of money and in prices. Changes in the supply of money affect individual prices and wages in different ways.”

For example, it doesn’t mean just because gold prices hasn’t continually been going up that the inflationary process are being subverted by deflation.

As Henry Hazlitt poignantly lay out the divergent effects of inflation in What You Should Know About Inflation (bold highlight mine) ``Inflation never affects everybody simultaneously and equally. It begins at a specific point, with a specific group. When the government puts more money into circulation, it may do so by paying defense contractors, or by increasing subsidies to farmers or social security benefits to special groups. The incomes of those who receive this money go up first. Those who begin spending the money first buy at the old level of prices. But their additional buying begins to force up prices. Those whose money incomes have not been raised are forced to pay higher prices than before; the purchasing power of their incomes has been reduced. Eventually, through the play of economic forces, their own money-incomes may be increased. But if these incomes are increased either less or later than the average prices of what they buy, they will never fully make up the loss they suffered from the inflation.”

In short, inflation comes in stages.

Let us use the example from the recent boom-bust cycle…

When the US dot.com bust in 2000 prompted the US Federal Reserve to cut interest rates from 6% to 1%, the inflationary pressures had initially been soaked up by its household sector which amassed household debts filliped by a gigantic punt in real estate.

As the speculative momentum fueled by easy money policies accelerated, monetary inflation were ventilated through three ways:

1. An explosion of the moneyness of Wall Street’s credit instruments which directly financed the housing bubble.

Credit Bubble Bulletin’s Doug Noland has the specifics, ``As is so often the case, we can look directly to the Fed’s Z.1 “flow of funds” report for Credit Bubble clarification. Total (non-financial and financial) system Credit expanded $1.735 TN in 2000. As one would expect from aggressive monetary easing, total Credit growth accelerated to $2.016 TN in 2001, then to $2.385 TN in 2002, $2.786 TN in 2003, $3.126 TN in 2004, $3.553 TN in 2005, $4.025 TN in 2006 and finally to $4.395 TN during 2007. Recall that the Greenspan Fed had cut rates to an unprecedented 1.0% by mid-2003 (in the face of double-digit mortgage Credit growth and the rapid expansion of securitizations, hedge funds, and derivatives), where they remained until mid-2004. Fed funds didn’t rise above 2% until December of 2004. Mr. Greenspan refers to Fed “tightening” in 2004, but Credit and financial conditions remained incredibly loose until the 2007 eruption of the Credit crisis.” (bold highlight mine)

2. These deepened the current account deficits, which signified the US debt driven consumption boom.

Again the particulars from Mr. Noland, ``It is worth noting that our Current Account Deficit averaged about $120bn annually during the nineties. By 2003, it had surged more than four-fold to an unprecedented $523bn. Following the path of underlying Credit growth (and attendant home price inflation and consumption!), the Current Account Deficit inflated to $625bn in 2004, $729bn in 2005, $788bn in 2006, and $731bn in 2007.” (bold highlight mine)

3. The subsequent sharp fall in the US dollar reflected on both the transmission of the US inflationary process into the world and the globalization of the credit bubble.

Again Mr. Noland for the details, ``And examining the “Rest of World” (ROW) page from the Z.1 report, we see that ROW expanded U.S. financial asset holdings by $1.400 TN in 2004, $1.076 TN in 2005, $1.831 TN in 2006 and $1.686 TN in 2007. It is worth noting that ROW “net acquisition of financial assets” averaged $370bn during the nineties, or less than a quarter the level from the fateful years 2006 and 2007.”

In short, the inflationary process diffused over a specific order of sequence, namely, US real estate, US financial debt markets, US stock markets, global stock markets and real estate, commodities and lastly consumer prices.

Past Reflation Scenarios Won’t Be Revived, A Possible Rush To Commodities

Going into today’s crisis, we can’t expect an exact reprise of the most recent past as the US real estate and the US financial debt markets are likely to be still encumbered by the deleveraging process see figure 4.

Figure 4: SIFMA: Non Agency Mortgage Securities and Asset Backed Securities

Figure 4: SIFMA: Non Agency Mortgage Securities and Asset Backed Securities

Some of the financial instruments such as the Non-Agency Mortgage Backed Securities (left) and Asset Backed Securities (right), which buttressed the real estate bubble have materially shriveled and is unlikely to be resuscitated even by the transfer of liabilities to the government.

Besides, the general economic debt levels remain significantly high relative to the economy’s potential for a payback, especially under the weight of today’s recessionary environment.

Which is to say that today’s inflationary setting will probably evolve to a more short circuited fashion relative to the past.

This leads us to surmise that most of global stock markets (especially EM economies which we expect to rise faster in relative terms) could rise to absorb the collective inflationary actions led by the US Federal Reserve but on a much divergent scale. Currency destruction measures will also possibly support OECD prices but could underperform, as the onus from the tug-of-war will probably remain as a hefty drag in their financial markets.

And this also suggests that commodity prices will also likely rise faster (although not equally in relative terms) than the previous experience which would eventually filter into consumer prices.

In other words, the evolution of the opening up of about 3 billion people into the global markets, a more integrated global economy and the increased sophistication of the financial markets have successfully imbued the inflationary actions by central banks over the past few years. But this isn’t going to be the case this time around-unless economies which have low leverage level (mostly in the EM economies) will manage to sop up much of the slack.

Take for example China. China’s economy has generally a low of leverage which allows it the privilege of taking on more debts.

Figure 5: US Global Investors: China Loans and Fixed Asset Investment Surge

Figure 5: US Global Investors: China Loans and Fixed Asset Investment Surge

And that’s what it has been doing today in the face of this crisis-China’s national stimulus and monetary easing programs is expected to incur deficits of about 3-7% of its GDP coupled by the QE measures instituted by the US has impelled a recent surge in China’s domestic bank loans and real fixed investments.

Qing Wang of Morgan Stanley thinks that the US monetary policy measures has lowered “the opportunity cost of domestic fixed-asset investment”, which means increasing the attractiveness of Chinese assets.

According to Mr. Wang, ``In practice, lower yields on US government bonds means lower returns on the PBoC’s assets. This should enable the PBoC to lower the cost of its liabilities by: a) lowering the coupon interest rates it pays on the PBoC bills, which is a major liability item on its balance sheet; b) lowering the ratio of required reserves (RRR) on which the PBoC needs to pay interest; or c) lowering the interest rates that the PBoC needs to pay on the deposits of banks’ required reserves and excess reserves, currently at 1.62% and 0.72%, respectively. These potential changes should then lower the opportunity cost of bank lending from the perspective of individual banks.” (bold highlights mine)

In other words, low interest rates in the US can serve as fulcrum to propel a boom in China’s bank lending programs.

This brings us to the next perspective, which assets will likely benefit from such inflationary activities.

Henry Hazlitt gives us again a possible answer ``In answer to those who point out that inflation is primarily caused by an increase in money and credit, it is contended that the increase in commodity prices often occurs before the increase in the money supply. This is true. This is what happened immediately after the outbreak of war in Korea. Strategic raw materials began to go up in price on the fear that they were going to be scarce. Speculators and manufacturers began to buy them to hold for profit or protective inventories. But to do this they had to borrow more money from the banks. The rise in prices was accompanied by an equally marked rise in bank loans and deposits.” (bold highlight mine)

This suggests that expectations for more inflation are likely to trigger rising prices and growing shortages, which will likely be fed by more money printing, and eventually an increase in credit uptake in support these actions.

Some Proof?

China is on a bargain hunting binge for strategic resources, according to the Washington Post March 19th, ``Chinese companies have been on a shopping spree in the past month, snapping up tens of billions of dollars' worth of key assets in Iran, Brazil, Russia, Venezuela, Australia and France in a global fire sale set off by the financial crisis.

``The deals have allowed China to lock up supplies of oil, minerals, metals and other strategic natural resources it needs to continue to fuel its growth. The sheer scope of the agreements marks a shift in global finance, roiling energy markets and feeding worries about the future availability and prices of those commodities in other countries that compete for them, including the United States.”

China has also engaged in a record buying of copper, according to commodityonline.com March 14th, ``China has started to buy copper in a big way again. As part of the country’s strategy to make use of the recessionary trends in the global markets, China has hiked its copper buying during the past few months…

``According to recently released data, China’s copper import hit a record high of 329,300 tonnes in February, up 41.5 per cent from the 232,700 tonnes of January.”

Summary and Conclusion

Overall, these are some important points to ruminate on:

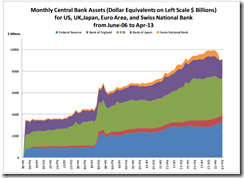

-It is clear that the thrust by the US government seems to be to reduce the real value of its outstanding liabilities by devaluing its currency. Since the US dollar is the world’s de facto currency reserve the path of the US government policy actions will be transmitted via its exchange rate value to the global financial markets and the world’s real economy. And this translates to greater volatility of the US dollar. Moreover, except for the ECB (yet), the QE efforts by most of the major central banks could translate to a race to the bottom in terms of devaluing paper money values.

-Collaborative global policy measures to inflate the world appear to be gaining traction in support of asset prices but at the expense of currency values.

-Global central bankers have been trying to revive inflationary expectations that are effectively “reflexive” in nature. By painting the perception of a ‘recovery’ through a rising tide of the asset markets, officials hope that this might induce a torrent of asset buying from a normalization of the credit process.

-The monumental efforts by global central banks to collectively turbocharge the global asset markets could eventually spillover to consumer prices and “surprise” mainstream analysts over their insistence to “tunnel” over the deflation angle. We expect higher consumer prices to come sooner than later especially if EM economies would be unable to fill the role of raising levels of systemic leveraging.

-Money isn’t neutral which means that the impact of inflation won’t be the same for financial assets and the real economy. Some assets or industries will benefit more than the others.

-We can’t expect the same “reflation” impact of the past episode to happen again as the ongoing tug-of-war between market-based debt deflation and government’s fixation to inflate the system has displaced the gains derived from the previous trends of globalization and the sophistication of financial markets. The US real estate markets will have surpluses to work off and the financial markets that financed the US real estate markets will remain broken for sometime and will take substantial number of years to recover.

-The impact of inflation will come in stages and perhaps accelerate in phases.

-The risk is that inflation could rear its ugly head in terms of greater than expected consumer prices earlier than what the consensus or policymakers expect. And if this is the case then it could pose as management dilemma for policymakers as the real economy remains weak and apparently fragile from the excessive dependence on the government and from the intense distortion brought about by government intervention in the marketplace. To quote Morgan Stanley’s Manoj Pradhan, ``Can QE be rolled back quickly? In theory, yes! Both passive and active QE could be reversed very quickly. The desire to hike rates above their currently low levels complicates matters slightly. Why? The effectiveness of passive QE depends on the willingness of banks to seek returns in the economy rather than simply parking excess reserves with the central bank. Hiking interest rates would reduce these incentives.”

Finally as we previously said it is increasingly becoming a cash unfriendly environment.