You know that we talk a lot about the insane level of government interference in our lives. About what we can and cannot put in our bodies. The amount of interest we’re entitled to receive on our savings. Etc.But I’m noticing now even more ridiculous trends of governments wanting to get involved in people’s sex lives.Last year the Danish government promoted an initiative called “Do it for Denmark”, encouraging Danes to travel abroad and have sex while on holidays. They even have a pretty racy Youtube video featuring a scantily clad gorgeous blonde waiting to do her duty for her country and procreate.Singapore as well has a catchy jingle about going out and making babies, brought to you by the same guys who did the Mentos theme song.The Swedish government actually spent taxpayer money on its new genitals song, so it can start indoctrinating children early on how they can make babies.Here in Japan, which has one of the lowest birthrates in the world, the government is desperate to find solutions to what it calls its libido crisis.According to their data, Japanese men aren’t terribly interested in sex and the women find sex to be bothersome.Japanese being expert process engineers are coming up with a government solution to reengineer sexual desire in their country.(I have to imagine that if this solution reached US soil, the government option would include the smooth sounds of Barack Obama whispering some pillow talk: “C’mon, lemme give you this big tax cut, baby…”)Easily the most ridiculous solution they came up with is to impose a ‘handsome tax’ on attractive men. I thought this was a headline from the Onion, the greatest news source in the world, but it turned out to be true.The idea being that if you tax handsome men, then less attractive men would have more money and hence be able to attract women.Zerohedge covered this in fantastic detail—I encourage you to check it out. This is not a joke.The thing that many of these countries have in common, Japan, Denmark, etc., is a rapidly declining birthrate.A declining birthrate is disastrous for an economy, particularly for an ageing place like Japan.Ironically, the oldest person in the world turned 117 years old yesterday—and no surprise that she’s Japanese. In fact, Japan is home to one of the oldest populations in the world and has one of the longest life expectancies.Curiously they also have one of the largest pension programs in the world. You put all that together and you have fewer and fewer young people paying more and more of their income to support a disproportionately large population of retirees who are living for decades after they stop working.Each one of these governments is trying to find a solution to fix this unsustainable fiscal problem.In Denmark they seem to think that people aren’t going on vacation enough. In Japan they think it’s a problem of sexual desire. But in actuality it has everything to do with cost of living.Month to month, year to year, it’s hard to notice the subtle changes in costs of living and standards of living, but after a long period of time it’s easy to look back and remember how things used to be.You used to be able to support a family on a single income. You used to be able to afford medical care and higher education.It’s often said that the greatest expense that someone will have in their life is his or her home. That’s total nonsense.Now, I’m not saying it’s not worth it, but the biggest expense most people will have is family, and particularly children.And after years and years of suffering through pitiful, destructive policies that have chronically made people less prosperous, it’s no surprise that they’re coming to the conclusion—you know, we can’t really afford to have a child right now.There are consequences to conjuring money out of thin air. There are consequences to destructive policies.So destructive in fact that central bankers and politicians even have the power to make a population disappear.How ironic that they try to fix their own problem by trying to introduce themselves into our bedrooms.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Saturday, March 07, 2015

The Effects of Inflationism on Sex Life

Saturday, January 18, 2014

How Western Environmentalism Shaped China’s One Child Policy

As China’s one-child policy comes officially to an end, it is time to write the epitaph on this horrible experiment — part of the blame for which lies, surprisingly, in the West and with green, rather than red, philosophy. The policy has left China with a demographic headache: in the mid-2020s its workforce will plummet by 10 million a year, while the number of the elderly rises at a similar rate.The difficulty and cruelty of enforcing a one-child policy was borne out by two stories last week. The Chinese film director Zhang Yimou, who directed the Beijing Olympics’ opening ceremony in 2008, has been fined more than £700,000 for having three children, while another young woman has come forward with her story (from only two years ago) of being held down and forced to have an abortion at seven months when her second pregnancy was detected by the authorities.It has been a crime in China to remove an intra-uterine device inserted at the behest of the authorities, and a village can be punished for not reporting an illegally pregnant inhabitant.I used to assume unthinkingly that the one-child policy was a communist idea, just another instance of Mao’s brutality. But the facts clearly show that it was a green idea, taken almost directly from Malthusiasts in the West. Despite all his cruelty to adults, Mao generally left reproduction alone, confining himself to the family planning slogan “Later, longer, fewer”. After he died, this changed and we now know how.Susan Greenhalgh, a professor of anthropology at Harvard, has uncovered the tale. In 1978, on his first visit to the West, Song Jian, a mathematician employed in calculating the trajectories of missiles, sat down for a beer with a Dutch professor, Geert Jan Olsder, at the Seventh Triennnial World Congress of the International Federation of Automatic Control in Helsinki to discuss “control theory”. Olsder told Song about the book The Limits to Growth, published by a fashionable think-tank called the Club of Rome, which had forecast the imminent collapse of civilisation under the pressure of expanding population and shrinking resources.

Saturday, December 15, 2012

Graphic: America’s Demographics: Racial and Ethnic Trends

By 2060, non-whites will make up 57% of the U.S. population, more than doubling from 116.2 million in 2012 to 241.3 million, according to projections by the U.S. Census Bureau. A surge in Hispanics and Asians is set to dramatically change the face of the United States over the next 50 years, with no one ethnic group the majority. Today’s graphic looks at this projected demographic change in more detail.

If your racial and ethnic voter base is aging, shrinking and dying, your moral code is being rejected, and the tax-consuming class has been allowed to grow to equal or to dwarf the taxpaying class, the Grand Old Party has a problem. But then so, too, does the country.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Why Not to Pay Heed to the Prophets of Ecological Apocalypse

Emotions based issues sell because people are emotional animals. Yet among all the emotions it is fear which is most powerful. That’s why horror movies sell, stock market crashes occur [where fear is a symptom and an accelerator of the market process], and that’s why many fall prey easily to "fear" based politics (e.g. climate change, peak resources and etc…).

Doomsayers sell or are popular also because of many people’s attachment to the Pessimism bias or the bias which exaggerates the likelihood of a negative outcome.

The profound Matthew Ridley writing at the Wired.com chronicles a list of prediction failures made by prophets of the apocalypse or Armageddon.

Ironically, despite the string of utter prediction failures; fear based issues remain in high demand. These have been evident in four fronts of social affairs, particularly in chemicals, diseases, people and resources. Mr. Ridley calls them the four horsemen of the apocalyptic promises

Here is an excerpt from the article.

Religious zealots hardly have a monopoly on apocalyptic thinking. Consider some of the environmental cataclysms that so many experts promised were inevitable. Best-selling economist Robert Heilbroner in 1974: “The outlook for man, I believe, is painful, difficult, perhaps desperate, and the hope that can be held out for his future prospects seem to be very slim indeed.” Or best-selling ecologist Paul Ehrlich in 1968: “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s ["and 1980s" was added in a later edition] the world will undergo famines—hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked on now … nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.” Or Jimmy Carter in a televised speech in 1977: “We could use up all of the proven reserves of oil in the entire world by the end of the next decade.”

Predictions of global famine and the end of oil in the 1970s proved just as wrong as end-of-the-world forecasts from millennialist priests. Yet there is no sign that experts are becoming more cautious about apocalyptic promises. If anything, the rhetoric has ramped up in recent years. Echoing the Mayan calendar folk, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved its Doomsday Clock one minute closer to midnight at the start of 2012, commenting: “The global community may be near a point of no return in efforts to prevent catastrophe from changes in Earth’s atmosphere.”

Over the five decades since the success of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and the four decades since the success of the Club of Rome’s The Limits to Growth in 1972, prophecies of doom on a colossal scale have become routine. Indeed, we seem to crave ever-more-frightening predictions—we are now, in writer Gary Alexander’s word, apocaholic. The past half century has brought us warnings of population explosions, global famines, plagues, water wars, oil exhaustion, mineral shortages, falling sperm counts, thinning ozone, acidifying rain, nuclear winters, Y2K bugs, mad cow epidemics, killer bees, sex-change fish, cell-phone-induced brain-cancer epidemics, and climate catastrophes.

So far all of these specters have turned out to be exaggerated. True, we have encountered obstacles, public-health emergencies, and even mass tragedies. But the promised Armageddons—the thresholds that cannot be uncrossed, the tipping points that cannot be untipped, the existential threats to Life as We Know It—have consistently failed to materialize. To see the full depth of our apocaholism, and to understand why we keep getting it so wrong, we need to consult the past 50 years of history.

The classic apocalypse has four horsemen, and our modern version follows that pattern, with the four riders being chemicals (DDT, CFCs, acid rain), diseases (bird flu, swine flu, SARS, AIDS, Ebola, mad cow disease), people (population, famine), and resources (oil, metals). Let’s visit them each in turn.

Read the rest here

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

How Reliable is CNBC’s Rankings of the Best Countries with Long Term Growth?

CNBC recently came out with a slide show depicting that troubles in the Eurozone and in the US has been prompting investors to search for new or alternative markets to invest in. And based on their selections mainly derived from demographics, natural resources or geography they came up with the following list:

10 Algeria

9. China

8. Egypt

7. Vietnam

6. Malaysia

5. Bangladesh

4 India

3 Peru

2 Ukraine

And the winner of CNBC’s best countries for long term growth…

…is the Philippines.

Given the endowment effect or home bias I should be screaming “yehey, buy buy buy the Philippines!”

Here is what CNBC has to say on the Philippines

1. Philippines

Projected annual growth: 7%

2010: $112 billion*

2050 projected GDP: $1.688 trillion

The Philippines has one of the fastest-growing populations in Asia. The population is set to jump by almost 70 percent over the next 40 years, and HSBC believes the combination of its powerful demographics and strong fundamentals will drive the economy to become the world’s 16th largest by 2050. That would mark a jump of 27 places from its current ranking of 43.

The country is one of the world’s largest exporters of labor, with over 9 million Filipinos working abroad, according to the latest data from the Commission of Filipinos Overseas. In 2010, almost $19 billion was sent back to the Philippines as remittances from Filipinos working abroad.

More recently, the country’s fast-developing business process outsourcing (BPO) industry has helped keep some of the workforce from leaving the country. Already 350,000 Filipinos are estimated to work in call centers, compared with 330,000 Indians, according to the Contact Center Association of the Philippines. The industry is projected to provide more than 1 million jobs within two years.

The economy’s focus on the services sector and domestic consumption, as well as a lower exposure to global financial markets, helped it to escape a recession following the 2008 global financial crisis.

It would seem as reductio ad absurdum to predict on long term growth based simply on variables of natural resources, demographics and or geography.

If these variables have been instrumental in generating prosperity, then the linkages should have been evident today.

Yet in looking at the world’s top 20 wealthiest nations based on per capita income from Wikipedia.org we see limited influences of abundant natural resources, young populations (demographics) or geography.

Why?

Countries with natural resources are usually afflicted by what is known as resource curse, which according to Wikipedia.org

refers to the paradox that countries and regions with an abundance of natural resources, specifically point-source non-renewable resources like minerals and fuels, tend to have less economic growth and worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources. This is hypothesized to happen for many different reasons, including a decline in the competitiveness of other economic sectors (caused by appreciation of the real exchange rate as resource revenues enter an economy), volatility of revenues from the natural resource sector due to exposure to global commodity market swings, government mismanagement of resources, or weak, ineffectual, unstable or corrupt institutions (possibly due to the easily diverted actual or anticipated revenue stream from extractive activities).

In reality, the biggest reason why the resource curse occurs has been due to the cartelization of resource based industries by politicians and their oligarchic cronies. These have mostly led to a political economic regime that have been anchored on anti-competition regulations which inhibits external and domestic trade.

Also it would be pretty naïve to focus on geography when vastly improving modes of transportation have been reducing the attendant costs.

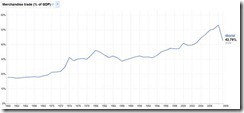

Transport, Insurance and freight costs as share of import cost have been on a secular decline

Mark Dean of the Bank’s International Economic Analysis Division and Maria Sebastia-Barriel of the Bank’s Structural Economic Analysis Division notes in the following study,

One of the most obvious costs to international trade is the cost of transporting goods from one country to another. Transport technologies are continually improving and transport services are also becoming cheaper through increased competition. The goods transported are also changing; some goods are now transported electronically, such as newspapers and magazines, due to improvements in communication technology and others are becoming lighter, for example mobile phones. All this should be reflected in lower transport costs.

In short, falling transaction costs diminishes the impact of geographic vantages.

Finally while I agree that “go forth and multiply” should generally be positive for the global economy; that link may not be obvious.

Most of the nations with the fastest population growth (table from Wikipedia) have hardly been the best economic growth performers. To the contrary most have been economic bottom dwellers.

The fundamental reason is that commercial activities have been severely restrained due to lack of property rights, deficiency in the rule of law, failure to protect contractual rights and limitations to voluntary productive exchanges. Also the political economic environment by many of these economies can be characterized as having been plagued by despotism and socialism. So the positive effects of population growth have been stunted, instead large populations morphs into a social burden.

Next, based on population growth, Indonesia has far outsprinted CNBC’s top 10 (chart from Google Public Data).

Indonesia has likewise been a resource rich country, and as our neighbor has been endowed with geographic advantages. So it would be a curiosity for me that Indonesia has been glossed over by CNBC.

And in terms of debt management, (chart from tradingeconomics.com) Indonesia has thus far bested the Philippines.

While this is both good news for the Philippines and Indonesia, the bottom line is that CNBC’s coverage hardly seems objective. There must be some undeclared biases in their methodology, such that even considering the few specious variables they can be amiss of other major potential contenders for investors, as Indonesia or Thailand.

And finally too much reliance on domestic consumption is unsustainable. This has been the Keynesian mantra embraced by mainstream media.

When excess consumption (government and private) in the Philippines will get manifested in the current account balance, which has still been positive today due to remittance and portfolio flows, the country’s declining debt to gdp trend will reverse and deteriorate.

Current negative real rates policies have already been adding to consumption activities via an artificially stimulated boom from domestic monetary policies by the BSP.

Yet the obverse side of a boom is a bust. And that’s hardly a long term positive growth proposition.

[As a caveat I don’t trust government statistics considering that almost two fifth of the Philippine economy is considered informal or underground or shadow. There are yet many factors not captured by statistical aggregates.]

Finally it should be a reminder that the key to prosperity is through attaining trade competitiveness (chart from the WEForum) via economic freedom or a deepening of the market economy or capitalism. The most competitive nations have almost reflected on the same standings as with the most prosperous nations.

To quote the great Ludwig von Mises

Capitalism is essentially a system of mass production for the satisfaction of the needs of the masses. It pours a horn of plenty upon the common man. It has raised the average standard of living to a height never dreamed of in earlier ages. It has made accessible to millions of people enjoyments which a few generations ago were only within the reach of a small elite.

Apparently, that’s not in the equation of CNBC. When reality is dealt with a blackout occurs.

Tuesday, November 01, 2011

7 Billion People: Boon or Bane?

The United Nations says that world population have reached 7 billion.

In attempting to visualize the impact of 7 billion people The Economist writes,

THE UN's doughty demographers have declared that October 31st is the day on which the world's population reached 7 billion. They may be wrong (the UN got the timing of the 6 billionth birth out by a couple of years) but no matter: the announcement has triggered celebrations in maternity wards around the globe and a hunt for the 7 billionth child. Yet the growth in the world’s population is actually slowing. The peak was in the late 1960s, when it was rising by almost 2% a year. Now the rate is half that. The last time it was so low was in 1950, when the death rate was much higher. The result is that the next billion people will take 14 years to arrive, the first time that a billion milestone has taken longer to reach than the one before. The billion after that will take 18 years. Where will all these people fit? The chart below, worked out on a maximum population density of six Economist staffers per square metre, gives the space needed to accommodate the world's population at various points in history, expressed in multiples of the borough of Manhattan. Looked at another way, each of us now has the equivalent of Red Square to ourselves.

7 billion represents merely a statistical estimate which most likely is an inaccurate measure of the real number of the world’s population.

Yet, the UN’s declaration seems loaded with political inferences.

For instance, the Economist article above tries to project maximum land allocated per individual or a population density. But this would be a chimera for the simple reason that all land area are not the same (e.g. mountains are different from coastline or from hills or from plateau; there are private owned and public owned) and that each individual does not use up or require as much space as what the Economist implies.

So the framing from the 7 billion figure could essentially foster political alarmism over a potential conflict from growing population relative to the scarcity of land which is fundamentally not only false but unrealistic.

The other implication of the UN’s hype is to give neo-Malthusians (who falsely believed that overpopulation would translate to a catastrophe for mankind or the Malthusian Catastrophe) room to advocate for more political controls on everyone. Their focal point has been centered on the strains to access scarce resources and to the environmental impact from a growing population.

Following charts from World Bank-Google Public Data

Yet even if there is some semblance of truth to the claim that we are now 7 billion people, the $7 billion question is that how have we been able to successfully reach this state in defiance of the doom mongers’ expectations of a ‘catastrophe’? And importantly if such factors will continue to support even a larger population?

The Economist rightly points out that world fertility rate have been going down.

If this slowing fertility trend should continue, then population growth trends would imply for a slowdown or even a potential peaking.

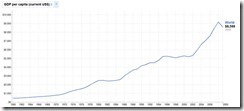

Nevertheless, another very important aspect that has supported today’s 7 billion people has been a huge jump in GDP per capita that coincides with the slowing fertility growth

The substantial improvement in per capita GDP has mostly been because of globalization and a more pervasive adaption of economic freedom.

Competition in free markets has been cultivating and accelerating the rate of technological innovations that has helped in resolving the scarcity problem in many aspects such as in the science and medicine, information and communications, business process and etc..

Largely uncelebrated hero Norman Borlaug discovered high yielding wheat varieties which he combined with modern agricultural techniques which paved way for the green revolution. Mr. Borlaug was eventually awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and was known as the ‘father of green revolution’ who has been credited with saving over a billion people from starvation

And further advancements in technology whose costs have materially decreased have became available to a wider range of people which has increased people's lifespans

The very impressive author Matthew Ridley wearing his Julian Simon hat (the famous free market economist who made a controversial bet against Malthusian Paul Elrich and won) sums up at the Wall Street Journal on why population growth trends will slow

(bold emphasis mine)

Birth rates have gone down because of prosperity, not poverty. Everywhere it has occurred, it has followed a fall in child mortality and famine and an increase in income and education. The wider availability of contraception has been necessary, even vital, for this shift, but it has not been sufficient.

To a biologist, the demographic transition is both surprising and intriguing. No other species drops its birth rate when its food supply increases. Frankly, no expert has yet fully explained the phenomenon. It remains something of a demographic enigma.

The best guess is that modern society causes human beings to switch their reproductive strategy from quantity to quality. Thus, once child mortality drops and paid work becomes available to the children of subsistence farmers, parents become more interested in getting one or two children into education or jobs than in begetting lots of heirs and spares for the farm.

Whatever the explanation, history shows that top-down policies aimed directly at population control have generally proved less successful than bottom-up ones aimed at human welfare, which get population control as a bonus. The faster poor countries can grow their economies, the slower they will grow their populations.

While present developments has generated much progress, there are still many afflicted by poverty. That’s because there continues to be meaningful resistance in embracing a bottom up approach in dealing with socio-economic development.

It's really not about the number of people but the process or the means by which people use to sustain their living. This means, in general, the world is much better off with MORE PRODUCTIVE people.