Rushing in defence over growing concerns of the risks of asset bubbles, the Philippine central bank, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas conducted a real estate exposure test monitoring which included a partial banking stress test[1].

In the report the BSP has not explicitly issued a confirmation or a denial of the risks of a domestic bubble. But they placed into the context the following

-The Philippines’s total banking exposure on real estate was at Php 821.7 billion as of December 2012.

-The BSP continues to monitor the 20 percent cap on RELs since 1997 where current report includes “loans by developers of socialized and low-cost housing, loans to individuals, loans supported by non-risk collaterals or Home Guarantee Corporation guarantee as well as exposures by bank trust departments and thrift banks.”

-The thrust to examine the banking sector’s exposure in real estate “is in line with the BSP’s pursuit of financial stability”

-The BSP hasn’t shown any signs of worries, due to stable non-performing RELs ratio which was “reported at 3.7 percent as of end-December 2012”

-And the BSP seems confident there is enough capital to withstand any potential shocks “with capital adequacy ratio of tested U/KBs and TBs will stand at 15.77 percent despite a 50 percent simulated default on residential real estate loans.”

First of all, the BSP does not mention that Real Estate Loans (REL) at 821.7 billion pesos and with a total loan portfolio TLP (net of interbank lending) of 3,938.9 billion pesos, real estate loans as a share of TLP would now account for 20.86%.

And so if my interpretation of their data is accurate then the banking sector has essentially hit its speed limits on issuing loans to the property sector. Will the BSP put on the brake and reverse the boom? How?

Next, it isn’t clear what the BSP means by “financial stability”? If they are referring to controlling price inflation my question is—are there no opportunity costs in in implementing “financial stability” measures? Or why should moderating price inflation come at the costs of blowing asset bubbles?

Let me cite the former chief of Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank of International Settlement’s William R. White in his 2006 paper who argued against price stability policies (bold mine)[2]

…price stability is indeed desirable for a whole host of reasons. At the same time, it will also be contended that achieving near-term price stability might sometimes not be sufficient to avoid serious macroeconomic downturns in the medium term. Moreover, recognising that all deflations are not alike, the active use of monetary policy to avoid the threat of deflation could even have longer term costs that might be higher than the presumed benefits. The core of the problem is that persistently easy monetary conditions can lead to the cumulative build-up over time of significant deviations from historical norms – whether in terms of debt levels, saving ratios, asset prices or other indicators of “imbalances”.

Also Non Performing Loans (NPLs) are coincident if not lagging indicators. NPLs are low because the current boom continues. NPLs become reliable indicators, when asset quality deteriorates or when the credit boom is in the process of reversing itself into a bust. Again they are coincident if not lagging indicators.

In addition, the BSP appears to have isolated its bank stress test by limiting “simulated default on residential real estate loans”. Why? Doesn’t the BSP know that economies are complex and vastly interdependent such that economies do not operate on isolation as the BSP model presumes?

A bursting bubble will ripple through not only through the residential real estate segment but would also impact commercial property sectors (office, shopping malls, casinos etc...) or firms that are highly leveraged.

More importantly, once the real estate sector gets slammed by the entwined factors of financial losses and deleveraging, such will likewise impact all sectors that have exposure on them, and so with the banks.

And affected secondary sectors will also hit firms from different industries connected to them, and so forth.

Thus the complex latticework of commercial networks means that the feedback mechanisms from the bubble busts will have a domino effect and thus spawn a crisis.

So models will not be able to capture the contagion effects from a real-estate-stock market bust for the simple reason that models tend to mathematically oversimplify what truly is a complex reality.

The fundamental flaw with BSP’s implied defence of the risks of asset bubbles has been to interpret statistics as economics.

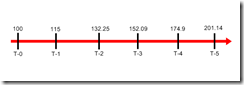

The above diagram represents the compounded average of 15%. A compounded average of 15% means a doubling of anything in 5 years. This applies to leveraging or economic imbalances.

Let us assume that a doubling of leveraging or imbalances will put an economy to a state of vulnerability to financial risks. It would not be helpful to say that, if we are at the T-3 stage, where statistics show only 152.09, to claim that there is no risk because of the current state. While such statement may be true, it essentially denies the imminence based on the trajectory.

In other words, the shifting of the burden of risk analysis from the rate of growth to reading today’s numbers would represent as misleading analysis and a denial.

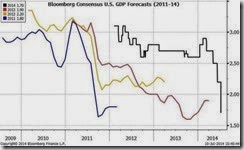

The same logic applies to a pre-debt crisis build up as shown by history.

.

In the chronicle of about 250 crisis in 8 centuries, Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff notes of the same pattern[3] (bold mine)

domestic debt is not static around default episodes. In fact, domestic debt often shows the same frenzied increases in the run-up to external default as foreign borrowing does. The pattern is illustrated in Figure 5, which depicts debt accumulation during the five years up to and including external default across all the episodes in our sample. Presumably, the comovement of domestic and foreign debt is produced by the same procyclical behavior of fiscal policy documented by previous researchers. As shown repeatedly over time, emerging market governments are prone to treating favorable shocks as permanent, fueling a spree in government spending and borrowing that ends in tears.

Again it is the trajectory that matters.

In short, it is the presence or absence of the factors that drives the incentives for these frenzied desire to accumulate debt that needs to be identified and curtailed.

Unfortunately since the genesis of such incentives have been political which have been effected through social policies, and from which the untoward impact from such polices are invisible and incomprehensible to the public, such policies will hardly be stopped until a blowback from the marketplace occurs.

And as for the state of euphoria, where governments think that they have reached a state of presumed perfection, the passing of the bank stress test in Cyprus in 2011 should serve as a fantastic example:

In Nicosia the Finance Ministry issued a statement saying: “The measures which the banks are taking or planning to take will further increase solvency.”

The statement also referred to a “removed possibility” of having to support the banks, stating the government was ready to “immediately take any necessary measures to maintain financial stability.”

BoC “successfully passed the test” because of its strong capital base, fluidity and satisfactory profitability, Bank of Cyprus’ Chief Executive Officer, Andreas Eliades.

Strong capital base, fluidity, increase solvency and satisfactory profitability, all turned on its head, March this year. The rest is history.

I know, the Philippines is not Cyprus. But the important lesson from the Cyprus episode is one of overconfidence that leads to complacency that further enhances systemic buildup of risks.

Remember bubbles are manifestations of the reflexive feedback loop between expectations as influenced by prices, and actions as influenced by expectations, which are enabled and facilitated by debt and incentivized by policies.

Overconfidence and complacency fosters systemic instability which is hardly “the pursuit of financial stability”

The BSP’s Wealth Transfer

These two charts embody the structural deficiencies of the Philippine political economy.

The BSP estimates that only 21.5% of households have access to the formal banking sector[5].

Yet domestic credit provided by the banking sector accounts for 51.54% of the GDP in 2011[6]. I would guess that the latter figure would be substantially higher today, given the credit boom mostly channelled through the banking sector.

Yet what these two diagrams say is that statistical economic growth has been immensely tilted towards those less than 21.5 households who have access and or have used credit from the banking system.

Not all depositors like me have used credit from the banking sector for whatever purpose. Yes I have credit cards but I which I use infrequently.

The BSP confirms this; they estimate that only 4% households have credit cards.

The lopsided exposure to the banking industry has been likewise reflected on the stock market.

As of 2011, according to Bloomberg/Matthews Asia[7] the wealthy elites control 83% of the market capitalization of the Philippine Stock Exchange

And considering the low penetration levels to the banking system and to the stock market, it would be even more conceivable that the general public hardly has any access to the more complex bond markets.

Again capital markets and the banking system have been greatly biased to the formal economy and to the oligarchs and plutocrats who control them.

Though we know that this has been an inherited problem, there has been little attempt by the powers-that-be to distribute them through liberalization ever since.

The procrastination by the PSE to hook up with the ASEAN trading link or the integration of ASEAN bourses[8] is an example. Philippine political and economic elites seem apprehensive over the prospects of losing their privileges with an ASEAN interconnection. The same applies with the lack of commodity markets where such markets would undermine the privileges of these plutocrats.

The much ballyhooed policy reforms has been more of the same. For example, government spending based on public-private partnerships, would only mean that the politically connected will be rewarded with such economic opportunities or concessions.

Yet foisting a zero bound rates in order to supposedly boost domestic demand doesn’t really help the real economy, for the simple reason that the informal economy has little direct access to the formal sector. And this will not change unless the government deregulates or liberalizes.

On the contrary credit easing policies has only boosted the wealth of the politically privileged elite.

As to quote anew the Atlantic[9]:

In 2012, Forbes Asia announced that the collective wealth of the 40 richest Filipino families grew $13 billion during the 2010-2011 year, to $47.4 billion--an increase of 37.9 percent. Filipino economist Cielito Habito calculated that the increased wealth of those families was equivalent in value to a staggering 76.5 percent of the country's overall increase in GDP at the time.

In short, BSP policies represent transfers of resources from the real economy to the political class (via bigger government spending and bigger bureaucracy) and politically connected economic elites.

Thus the manipulated boom, which has been peddled by media and bought for by the gullible public, has been used as license via populist mandate to extend on such privileges.

BSP’s Underbelly: The Philippines’ Shadow Banks

Now going back to the direction of BSP policies.

Promoting “domestic demand” through expanded access of credit has been the purported reason for zero bound rates and the lowering of interest rates of the SDAs[10].

Combine these with the recent credit rating upgrades from major international credit agencies, all these means subsidizing or rewarding debt. Thus the natural outgrowth of accelerating debt.

So the BSP’s direction has been to promote debt. But on the other hand they claim that they would regulate or control it. So the BSP essentially operates in a cognitive dissonance, holding two conflicting ideas as policies. This is a wonderful example of the idiom “the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing”: a self-contradiction

Now that the real estate sector has reached its limits as noted above, the question is will the BSP act?

Even if the BSP does, I am quite sure that many market participants would resort to regulatory arbitrage to circumvent them.

They may shift the use of loans even if they are classified as non-real estate into real estate or into the stock market, such as the fateful Bangladesh stock market crash in 2011[11]. Banks may use off balance sheets. Others may resort to bribery.

Of course, given the huge domestic informal economy, the most likely avenue for regulatory arbitrage is to use the nexus between the formal and the informal economy: the shadow banking system.

The BSP believes that they have the banking sector within their palms, but the World Bank says otherwise

Shadow banking system in Philippines and Thailand accounts for more than one-third of total financial system assets[12]. One would note in the right chart that the Philippine shadow banking system has seen an intensifying rate of growth which has polevaulted since 2009 and has nearly surpassed Thailand’s level.

Aside from common informal microfinancing[13] as 5-6 lending, “paluwagan” or pooled money, “hulugan” instalment credit, much of the growth in the shadow banking system has reportedly been in the real estate sector, particularly the in-house financing from developers[14].

The BSP claims that it would investigate[15] these even if they hardly control the formal system.

The shadow banking system has become a worldwide phenomenon and has grown to as high as $67 trillion in 2011 according to the CNBC[16] or nearly 83% of the $80 trillion world economy. The risks of the shadow banking sector doesn’t intuitively or automatically emerge out of “lack of regulation”, rather, the shadow banking industry has been largely a product of overregulation via regulatory arbitrage. Where an economic or financial system has been hobbled by politics, risks becomes centralized and thus systemic.

Bottom line: Loans to the real estate sector have significantly been more than the caps set by the BSP. Easy money policies have apparently filtered into the informal sector. This means systemic leverage has been far more than what the BSP oversees and supervises. Lastly the BSP hardly has solid control over the formal sector. The same is amplified with the informal or shadow banking system.

Like almost every central bankers today, BSP policies supposedly meant to promote “domestic demand” will be pushed to the limits, despite the rhetoric. And this will further fuel the mania phase in both the stock market and the property sector.