So claims popular analyst John Mauldin in his latest newsletter.

You don’t even have to go that far back to see hyperinflation and how brilliantly it works at eliminating debt. Let’s look at the example of Brazil, which is one of the world’s most recent examples of hyperinflation. This happened within our lifetimes. In the late 1980s and 1990s, it very successfully got rid of most of its debt.

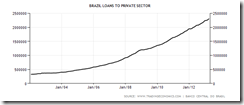

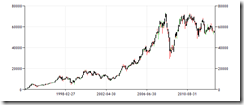

Today, Brazil has very little debt, as it has all been inflated away. Its economy is booming, people trust the central bank, and the country is a success story. Much like the United States had high inflation in the 1970s and then got a diligent central banker like Paul Volcker, in Brazil a new government came in, beat inflation, produced strong real GDP growth, and set the stage for one of the greatest economic success stories of the past two decades. Indeed, the same could be said of other countries like Turkey that had hyperinflation, devaluation, and then found monetary and fiscal rectitude.

In 1993, Brazilian inflation was roughly 2,000 percent. Only four years later, in 1997 it was 7 percent. Almost as if by magic, the debt disappeared. Imagine if the United States increased its money supply, which is currently $900 billion, by a factor of 10,000 times, as Brazil did between 1991 and 1996. We would have 9 quadrillion U.S. dollars on the Fed’s balance sheet. That is a lot of zeros. It would also mean that our current debt of 13 trillion would be chump change. A critic of this strategy for getting rid of our debt could point out that no one would lend to us again if we did that. Hardly. Investors, sadly, have very short memories. Markets always forgive default and inflation. Just look at Brazil, Bolivia, and Russia today. Foreigners are delighted to invest in these countries.

Sometimes I feel like dispensing the role of snopes.com a popular website which serves as “the definitive Internet reference source for urban legends, folklore, myths, rumors, and misinformation.”

Well, here is the account of Brazil’s inflation-debt dynamics according to the Wikipedia.org, (bold highlights mine)

The stabilization program, called Plano Real had three stages: the introduction of an equilibrium budget mandated by the National Congress a process of general indexation (prices, wages, taxes, contracts, and financial assets); and the introduction of a new currency, the Brazilian real, pegged to the dollar. The legally enforced balanced budget would remove expectations regarding inflationary behavior by the public sector. By allowing a realignment of relative prices, general indexation would pave the way for monetary reform. Once this realignment was achieved, the new currency would be introduced, accompanied by appropriate policies (especially the control of expenditures through high interest rates and the liberalization of trade to increase competition and thus prevent speculative behavior).

By the end of the first quarter of 1994, the second stage of the stabilization plan was being implemented. Economists of different schools of thought considered the plan sound and technically consistent.

1994-present (Post "Real Plan" economy)

The Plano Real ("Real Plan"), instituted in the spring 1994, sought to break inflationary expectations by pegging the real to the U.S. dollar. Inflation was brought down to single digit annual figures, but not fast enough to avoid substantial real exchange rate appreciation during the transition phase of the Plano Real. This appreciation meant that Brazilian goods were now more expensive relative to goods from other countries, which contributed to large current account deficits. However, no shortage of foreign currency ensued because of the financial community's renewed interest in Brazilian markets as inflation rates stabilized and memories of the debt crisis of the 1980s faded.

The Real Plan successfully eliminated inflation, after many failed attempts to control it. Almost 25 million people turned into consumers.

The maintenance of large current account deficits via capital account surpluses became problematic as investors became more risk averse to emerging market exposure as a consequence of the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the Russian bond default in August 1998. After crafting a fiscal adjustment program and pledging progress on structural reform, Brazil received a $41.5 billion IMF-led international support program in November 1998. In January 1999, the Brazilian Central Bank announced that the real would no longer be pegged to the U.S. dollar. This devaluation helped moderate the downturn in economic growth in 1999 that investors had expressed concerns about over the summer of 1998. Brazil's debt to GDP ratio of 48% for 1999 beat the IMF target and helped reassure investors that Brazil will maintain tight fiscal and monetary policy even with a floating currency.

In short, monetary reform via the dollar peg (first), fiscal austerity and the move towards greater economic freedom resulted to the reduction of Brazil’s debt.

Here is the account of the World Bank... (bold emphasis mine)

Brazil’s debt decomposition indicates that primary fiscal balances and real GDP growth have been the most significant debt-reducing factors between 1993 and 2003. Brazil’s primary fiscal balance, which has improved significantly in the recent past, has provided the largest debt-reducing contribution, in particular since 1999. Real GDP growth was responsible for a debt decline of 9.0 percent of GDP over the decade.

Apparently the World Bank says the same-fiscal side reforms functioned as the critical factor in Brazil’s debt reduction.

And here is a paper from the Inter-American Development Bank entitled The Structure of Public Sector Debt in Brazil

Afonso Sant’anna Bevilaqua, Dionísio Dias Carneiro, Márcio Gomes Pinto Garcia, Rogério Furquim Ladeira Werneck, Fernando Blanco, Patricia Pierotti, Marcelo Rezende, Tatiana Didier writes, (bold highlights mine, italics theirs)

Given Brazilian inflationary history, the domestic bonded debt market was recreated in the mid-1960s with the introduction of indexed bonds (ORTNs), which were then conceived as an antiinflationary tool. The idea was that only the money financing of the fiscal deficits was inflationary. In the period of more than thirty years since its creation, the Brazilian open market has evolved into a very sophisticated one. The gross bond debt held by the private sector is currently around one fourth of a trillion US dollars; the megainflation of the 1980s and early 1990s did not inflate away the Brazilian debt.

During the megainflation, most of the debt was placed with banks (and later, with mutual funds managed by the banks) which used the bonds as the asset counterpart of inflation protected deposits (the indexed money, or domestic currency substitute). With the Real Plan this situation is gradually changing. The debt maturity has been lengthened (with a few setbacks, as the recent Asian and Russian crises), and more agents interested in becoming final holders of long debt—as insurance companies and pension funds—are becoming more important in the financial arena.

A radical change in Brazil debt maturity profile and similarly a change in the classification of debt holders had also been a part of Brazil’s debt reduction dynamics. This paper even highlights: “the megainflation…did not inflate away the Brazilian debt”.

Bottom line: Beware of oversimplified misleading analysis.