Credit Expansion No Substitute for Capital. These opinions are passionately rejected by the union bosses and their followers among politicians and the self-styled intellectuals. The panacea they recommend to fight unemployment is credit expansion and inflation, euphemistically called an "easy money policy"—Ludwig von Mises

In this issue

Philippine Uni-Comm Bank Lending in 2024: Why Milestone Bank Credit Expansion and Systemic Leveraging Extrapolates to Mounting Systemic Fragility

I. Challenging the BSP’s Easing Cycle Narrative

II. How BSP’s Credit Card Subsidies Materially Transformed Banking Business Model

III. Bank Lending to Real Estate Expanded in 2024, Even as Sector’s GDP Slumped to All-Time Lows!

IV. Credit Intensity Hits Second-Highest Levels!

V. Redux: The Debt-to-GDP Myth: A Background

VI. The GDP is Mostly About Debt: 2024 Public Debt-to-GDP Reaches Second Highest Level Since 2005!

VII. The Mirage of Labor Productivity

VIII. Conclusion

Philippine Uni-Comm Bank Lending in 2024: Why Milestone Bank Credit Expansion and Systemic Leveraging Extrapolates to Mounting Systemic Fragility

Universal-commercial bank lending performance in 2024 provides some critical insights. Combined with public debt and GDP, these reveal rising financial and economic fragilities.

I. Challenging the BSP’s Easing Cycle Narrative

Inquirer.net, February 13, 2025: "Bank lending posted its fastest growth in two years to cross the P13-trillion mark in December, as the start of the interest rate-cutting cycle and the typical surge in economic activities during the holiday season boosted both consumer and business demand for loans. Latest data from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) showed that outstanding loans of big banks, excluding their lending with each other, expanded by 12.2 percent year-on-year to P13.14 trillion in the final month of 2024, beating the 11.1-percent growth in November. That was the briskest pace of credit growth since December 2022."

While the BSP kept its policy rate unchanged this week, it has engaged in an 'easing cycle' following three rate cuts, a substantial RRR reduction, and possibly record government spending in 2024.

Figure 1

The notion that the BSP's easing cycle has driven bank lending growth is not supported by the data. While December saw the "briskest...since December 2022," the 13.54% growth rate in that earlier period occurred near the peak of a hiking cycle, suggesting that neither rate hikes nor cuts significantly influence growth rates.

Official rates peaked in October 2023, ten months after the December 2022 lending surge.

II. How BSP’s Credit Card Subsidies Materially Transformed Banking Business Model

Unlike the BSP's 2018 interest rate cycle, where hikes coincided with falling bank lending rates, the current credit market anomalies likely reflect distortions caused by the BSP's pandemic-era policies. These included an interest rate cap on credit cards and various relief measures. (Figure 1, topmost image)

Specifically, the BSP's interest rate cap in September 2020 significantly reshaped or transformed the banking system's business model, demonstrably shifting focus from business to consumer loans.

The consumer share of universal-commercial (UC) bank loans surged by 27.4% over four years, increasing from 9.5% in 2020 to 12.1% in 2024. (Figure 1, middle window)

The biggest segment growth came from credit cards and salary loans:

-Credit card loans grew at a 22.3% CAGR from 2020 to 2024, increasing their share from 4.6% to 7.1% of total loans. Since 2018, their share has more than doubled from 3.4% to 7.1%. (Figure 1, lowest graph)

-Salary loans grew at an 18.07% CAGR over the same period, expanding their share from 0.9% to 1.2%.

Figure 2

-December's month-on-month (MoM) growth of 3.38% marked the highest since January 2022's 3.98%. Contrary to the assumption of seasonality, the highest monthly growth rates have not been confined to the holiday season. (Figure 2, topmost diagram)

This astronomical growth in consumer credit, further fueled by December's reacceleration, underscores the substantial leveraging of household balance sheets.

III. Bank Lending to Real Estate Expanded in 2024, Even as Sector’s GDP Slumped to All-Time Lows!

In 2024, real estate (Php 222.72 billion) and credit cards (Php 212.1 billion) saw the largest nominal increases in lending. Electricity and Gas, and trade, followed. (Figure 2, middle chart)

Supply-side real estate loans accounted for 20.5% of total UC bank loans at year-end. This figure excludes consumer mortgage borrowing.

However, while real estate's GDP share hit an all-time low of 5.4% in 2024, bank exposure to the sector reached its second-highest level. In Q3, BSP data revealed that real estate prices had entered deflationary territory. (Figure 2, lowest pane)

The continued decline in the sector's GDP raises mounting risks for banks.

Rising real estate loan growth does not necessarily indicate expansion but rather refinancing efforts or liquidity injections to prevent a surge in delinquencies and non-performing loans.

Figure 3

Moreover, key sectors benefiting from BSP’s rate policies—construction, trade, finance, and real estate—continue to represent a significant share of UC bank portfolios, which share of the GDP has also been rising, posing as systemic risk concerns. (Figure 3, topmost chart)

IV. Credit Intensity Hits Second-Highest Levels!

A broader perspective reveals more concerning trends.

UC total bank loans grew by 10.8% year-on-year, from Php 11.392 trillion in 2023 to Php 12.81 trillion in 2024 (a net increase of Php 1.42 trillion). In comparison, nominal GDP grew by 8.7%, from Php 24.32 trillion to Php 26.44 trillion (a net increase of Php 2.12 trillion).

This gives a 'credit intensity' of Php 0.67—the amount of bank lending needed to generate one peso of GDP—the highest since 2019. This means UC bank lending has recovered to pre-pandemic levels, while GDP hasn't.

Factoring in public debt (excluding guarantees), 2024 saw a sharp rise in credit dependency. Credit intensity from systemic debt (public debt + bank lending, excluding capital markets and shadow banking) reached its second-highest level ever, trailing only the peak of 2021.

It now takes Php 1.35 of debt to generate one peso of GDP, highlighting diminishing returns of a debt-driven economy. (Figure 3, middle image)

The mainstream thinks debt is a free lunch!

V. Redux: The Debt-to-GDP Myth: A Background

The BSP’s trickle-down policies operate under an architectural framework called "inflation targeting."

Though its stated goal is to 'promote price stability conducive to balanced and sustainable growth of the economy,' it assumes that inflation can be contained or that the inflation genie can be kept under control.

Its easy money regime has been designed as an invisible tax or a form of financial repression—primarily to fund political boondoggles—by unleashing "animal spirits" through the stimulation of "aggregate demand" or GDP. At the same time, GDP growth is expected to increase tax collections.

The fundamental problem is that the BSP has no control over the distribution of credit expansion within the economy.

As it happened, while the "liberalized" consumer-related sectors were the primary beneficiaries, distortions accumulated—principally as the elites took advantage of cheap credit to pursue "build-it-and-they-will-come" projects.

The result was the consolidation of firms within industries and the buildup of concentration risk. Soon, the cheap money landscape fueled the government’s appetite for greater control over the economy through deficit spending.

Thus, the "debt-to-GDP" metric became the primary justification for expanding government spending and increasing economic centralization.

This race toward centralization through deficit spending intensified alongside the elite’s "build-it-and-they-will-come" projects during the pandemic.

VI. The GDP is Mostly About Debt: 2024 Public Debt-to-GDP Reaches Second Highest Level Since 2005!

Once again, the consensus has a fetish for interpreting debt-to-GDP as if it were an isolated or standalone factor. It isn’t.

In the recent past, they cited falling debt-to-GDP as a positive indicator. However, let’s clarify: since the economy is interconnected—one dynamic entwined with another, operating within a lattice of interrelated nodes—such a simplistic view is misleading.

When the BSP forced down rates to reinforce its "trickle-down" policies, the consequences extended beyond public spending, affecting overall credit conditions. This policy catalyzed a boom-bust cycle.

As such, when the public debt-to-GDP declined between 2009 and 2019, it was primarily because bank credit-to-GDP filled most of the gap.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating: systemic leverage-to-GDP remained range-bound throughout that decade. Debt was merely transferred or juggled from the public to the private sector.

GDP growth, in large part, was debt-driven.

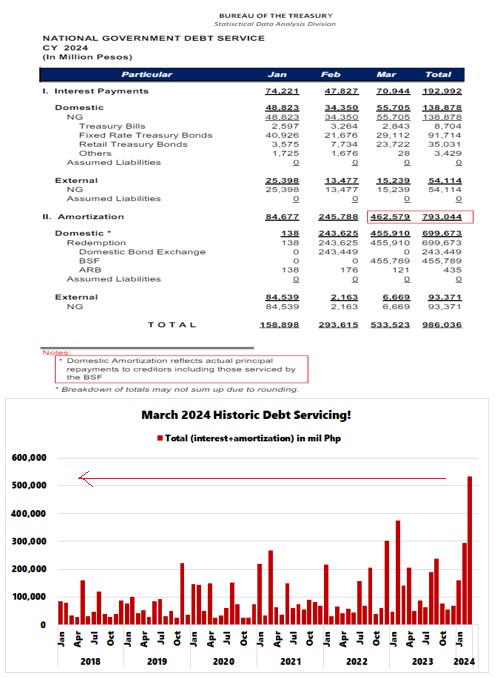

Yet, the pandemic-era bailout fueled a surge in both public debt-to-GDP and bank credit-to-GDP. Public debt-to-GDP (excluding guarantees) reached 60.72%—its second-highest level after 2022—following the BSP’s COVID-era bailout, which also marked the highest rate since 2005.

It’s worth remembering that Thailand—the epicenter of the 1997-98 Asian Crisis—had the lowest debt-to-GDP at the time. (Figure 3, lowest table)

More importantly, public debt has anchored government spending, which has played a crucial role in shaping Philippine GDP since 2016.

V. Systemic Leverage Soars to All-Time Highs!

Figure 4

On a per capita basis, 2024 debt reached historic highs, increasing its share of per capita GDP (both in nominal and real terms). (Figure 4, topmost visual)

Simply put, rising debt levels have been eroding whatever residual productivity gains are left from the GDP.

Alternatively, this serves as further proof that GDP is increasingly driven by debt at the expense of productivity.

It also implies that the deepening exposure of output to credit is highlighting its mounting credit risk profile.

In 2024, UC bank loans-to-GDP hit 48.5%, the second-highest since 2020 (49.7%), indicating crisis lending via easy money policies.

Systemic leverage reached a record 109.2% of GDP, surpassing 2022 ATH. (Figure 4, middle chart)

Despite a Q4 2024 liquidity spike (M3), consumers struggled; household GDP slowed, suggesting households are absorbing increasing leverage while enduring the erosion of purchasing power in the face of inflation. (Figure 4, lowest diagram)

Figure 5

Another point: The growth rate of systemic leverage has shown a strong correlation with the CPI since 2013. However, it appears to have deviated, as rising systemic leverage has yet to result in an accompanying increase in the CPI. Will this correlation hold? (Figure 5, topmost image)

VI BSP’s ‘Trickle-Down Policies’ Steered a Credit Card and Salary Loans Boom (and coming Bust)

There is more to consider. The banking model's transformation toward consumers didn’t happen overnight; it was the result of cumulative easy money policies that intensified during the pandemic.

Our central premise: while bank expansion fueled inflation, the pandemic-induced recession—marked by income loss—and, most notably, the BSP’s easy money emergency response (including historic interest rate and RRR cuts, various relief measures such as credit card subsidies, the USDPHP cap, and the unprecedented Php 2.3 billion BSP injections) sparked a consumer credit boom, which subsequently triggered the second wave of this inflation cycle.

Though the BSP’s intent may have been to compensate for consumers' income losses in order to stabilize or protect the banking system, the economic reopening further stirred up consumers’ appetite for credit, fueling demand amid a recovering, fractured, and impaired supply chain.

Debt-financed government spending also contributed to the surge in aggregate demand. Together, these factors spurred a rise in "too much money chasing too few goods" inflation.

The inflation genie was unleashed—yet it was conveniently blamed by everyone on the "supply side." The underlying premise of the echo chamber was that the demand-supply curve had been broken! Yet, they avoided addressing the question: How could a general price increase occur if the money supply remained stable?

Ironically, the BSP calibrated its response to the inflation cycle by adjusting interest rates in line with its own interest rate cycle! In other words, they blamed supply-side issues while focusing their policies on demand. Remarkable!

The BSP’s UC bank credit card and salary loan data provide evidence for all of this (Figure 5 middle and lowest graphs): the escalating buildup of household balance sheets in response to the loss of purchasing power, the CPI cycle, and the BSP and National Government’s free money policies.

Figure 6

It’s also no surprise that the oscillation of UC bank loan growth has mirrored fluctuations in the PSEi 30. (Figure 6, topmost window)

Unfortunately, the law of diminishing returns has plagued the massive growth of consumer credit, leading to its divergence from consumer spending and PSEi 30 flows.

As an aside, the upward spiral in cash in circulation last December and Q4 —reflecting both liquidity injections for the real estate industry and pre-mid-term election spending—likely points to higher inflation and the further erosion of consumer spending power. (Figure 6, middle chart)

Is it any wonder that self-reported poverty ratings and hunger have surged to record highs?

Does the path to 'middle-income status' for an economy translate into a population drowning in debt?

VII. The Mirage of Labor Productivity

Businessworld, February 10, 2025: The country’s labor productivity — as measured by gross domestic product per person employed — grew by 4.5% year on year to P456,342 in 2024. This was faster than the 2.7% a year earlier and the fastest in seven years or since the 8.7% in 2017. (Figure 6, lowest image)

While this suggests improving efficiency, it fails to account for GDP’s deepening dependence on credit expansion. When growth is primarily debt-financed, productivity gains become illusory.

Credit isn’t neutral. Its removal would cause the 'debt-driven GDP-labor productivity' 'castle in the sand' to crumble

VIII. Conclusion

The 2024 UC bank lending data reveals critical economic trends:

>A structural shift in the banking business model, driven by the BSP’s inflation-targeting and pandemic rescue policies.

>Mounting concentration risks due to industry consolidations and growing sector fragility.

>Public debt-to-GDP reaching its second-highest level since 2005, while systemic leverage has hit an all-time high.

Diminishing returns from the increasing dependence on systemic credit—bank expansion and public debt—highlighting the risks of financial and economic vulnerabilities and instability.

The Philippine political economy operates with a very thin or narrow margin for error.

In an upcoming issue, we are likely to address the banking system's 2024 income statement and balance sheets.