An ever-weaker private sector, weak real wages, declining productivity growth, and the currency’s diminishing purchasing power all indicate the unsustainability of debt levels. It becomes increasingly difficult for families and small businesses to make ends meet and pay for essential goods and services, while those who already have access to debt and the public sector smile in contentment. Why? Because the accumulation of public debt is printing money artificially—Daniel Lacalle

Nota Bene: Unless some interesting developments turn up, this blog may be the last for 2024.

In this issue

Low Prioritization in

the Banking System: The Magna Carta for MSMEs as a ‟Symbolic Law‟

I. MSMEs: The Key to Inclusive Growth

II. The Politicization of MSME Lending

III. Bank's MSME Loans: Low Compliance Rate as a Symptom of the BSP’s Prioritization of Banking Interests

IV. Suppressed MSME Lending and Thriving Shadow Banks: It’s Not About Risk Aversion, but Politics

V. Deepening Thrust Towards Banking Monopolization: Rising Risks to Financial System Stability

VI. How PSEi 30's Debt Dynamics Affect MSME Struggles

VII. The Impact of Bank Borrowings and Government Debt Financing on MSMEs’ Challenges

VIII. How Trickle-Down Economics and the Crowding Out Effect Stifle MSME Growth

IX. Conclusion: The Magna Carta for MSMEs Represents a "Symbolic Law," Possible Solutions to Promote Inclusive MSME Growth

Low Prioritization in the Banking System: The Magna Carta for MSMEs as a ‟Symbolic Law‟

Despite government mandates, bank lending to MSMEs reached its third-lowest rate in Q3 2024, reflecting the priorities of both the government and the BSP. This highlights why the Magna Carta is a symbolic law.

I. MSMEs: The Key to Inclusive Growth

Inquirer.net December 10, 2024 (bold added): Local banks ramped up their lending to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the third quarter, but it remained below the prescribed credit allocation for the industry deemed as the backbone of the Philippine economy. Latest data from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) showed total loans of the Philippine banking sector to MSMEs amounted to P500.81 billion in the three months through September, up by 3 percent on a quarter-on-quarter basis. But that amount of loans only accounted for 4.6 percent of the industry’s P11-trillion lending portfolio as of end-September, well below the prescribed credit quota of 10 percent for MSMEs. Under the law, banks must set aside 10 percent of their total loan book as credit that can be extended to MSMEs. Of this mandated ratio, banks must allocate 8 percent of their lending portfolio for micro and small businesses, while 2 percent must be extended to medium-sized enterprises. But many banks have not been compliant and just opted to pay the penalties instead of assuming the risks that typically come with lending to MSMEs.

Bank lending to the MSME sector, in my view, is one of the most critical indicators of economic development. After all, as quoted by the media, it is "deemed as the backbone of the Philippine economy."

Why is it considered the backbone?

Figure 1

According to the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), citing data from the Philippine Statistics Authority, in 2023, there were "1,246,373 business enterprises operating in the country. Of these, 1,241,733 (99.63%) are MSMEs and 4,640 (0.37%) are large enterprises. Micro enterprises constitute 90.43% (1,127,058) of total establishments, followed by small enterprises at 8.82% (109,912) and medium enterprises at 0.38% (4,763)." (Figure 1 upper chart)

In terms of employment, the DTI noted that "MSMEs generated a total of 6,351,466 jobs or 66.97% of the country’s total employment. Micro enterprises produced the biggest share (33.95%), closely followed by small enterprises (26.26%), while medium enterprises lagged behind at 6.77%. Meanwhile, large enterprises generated a total of 3,132,499 jobs or 33.03% of the country’s overall employment." (Figure 1, lower graph)

Long story short, MSMEs represent the "inclusive" dimension of economic progress or the grassroots economy—accounting for 99% of the nation’s entrepreneurs, and providing the vast majority of jobs.

The prospective flourishing of MSMEs signifies that the genuine pathway toward an "upper middle-income" status is not solely through statistical benchmarks, such as the KPI-driven categorization of Gross National Income (GNI), but through grassroots-level economic empowerment.

Except for a few occasions where certain MSMEs are featured for their products or services, or when bureaucrats use them to build political capital to enhance the administration’s image, mainstream media provides little coverage of their importance.

Why?

Media coverage, instead, tends to focus disproportionately on the elite.

Perhaps this is due to survivorship bias, where importance is equated with scale, or mostly due to principal-agent dynamics. That is, media organizations may prioritize advancing the interests of elite firms to secure advertising revenues, and or, maintain reporting privileges granted by the government or politically connected private institutions.

II. The Politicization of MSME Lending

Yet, bank lending to the sector remains subject to political directives—politicized through regulation.

Even so, banks have essentially defied a public mandate, opting to pay a paltry penalty: "The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas shall impose administrative sanctions and other penalties on lending institutions for non-compliance with provisions of this Act, including a fine of not less than five hundred thousand pesos (P500,000.00)." (RA 9501, 2010)

Figure 2

With total bank lending amounting to Php 10.99 trillion (net of exclusions) at the end of Q3, the compliance rate—or the share of bank lending to MSMEs—fell to 4.557%, effectively the third lowest on record after Q1’s 4.4%. (Figure 2, upper window)

That’s primarily due to growth differentials in pesos and percentages. For instance, in Q3, the Total Loan Portfolio (net of exclusions) expanded by 9.4% YoY, compared to the MSME loan growth of 6.5%—a deeply entrenched trend.(Figure 2, lower image)

Interestingly, "The Magna Carta for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)" was enacted in 1991 (RA 6977), amended in 1997 (RA 8289), and again in 2008 (RA 9501). The crux is that, as the statute ages, industry compliance has diminished

Most notably, banks operate under cartel-like conditions. They are supervised by comprehensive regulations, with the BSP influencing interest rates through various channels—including policy rates, reserve requirement ratios (RRR), open market operations, inflation targeting, discount window lending, interest rate caps, and signaling channels or forward guidance.

In a nutshell, despite stringent regulations, the cartelized industry is able to elude the goal of promoting MSMEs.

III. Bank's MSME Loans: Low Compliance Rate as a Symptom of the BSP’s Prioritization of Banking Interests

Yet, the record-low compliance rate with the Magna Carta for MSMEs points to several underlying factors:

First, banks appear to exploit regulatory technicalities or loopholes to circumvent compliance—such as opting to pay negligible penalties—which highlights potential conflicts of interest.

Though not a fan of arbitrary regulations, such lapses arguably demonstrate the essence of regulatory capture, as defined by Investopedia.com, "process by which regulatory agencies may come to be dominated by the industries or interests they are charged with regulating"

A compelling indication of this is the revolving-door relationship between banks and the BSP, with recent appointments of top banking executives to the BSP’s monetary board.

Revolving door politics, according to Investopedia.com, involves the "movement of high-level employees from public-sector jobs to private-sector jobs and vice versa"

The gist: The persistently low compliance rate suggests that the BSP has prioritized safeguarding the banking sector's interests over promoting the political-economic objectives of the Magna Carta legislation for MSMEs.

IV. Suppressed MSME Lending and Thriving Shadow Banks: It’s Not About Risk Aversion, but Politics

Two, with its reduced lending to MSMEs, banks purportedly refrain from taking risk.

But that’s hardly the truth.

Even with little direct access to formal or bank credit, MSME’s are still borrowers, but they source it from the informal sector.

Due to the difficulty of accessing bank loans, MSMEs in the Philippines are borrowing from informal sources such as the so-called 5-6 money lending scheme. According to an estimate, 5-6 money lending is now a Php 30 billion industry in the Philippines. These lenders charge at least 20% monthly interest rate, well above the 2.5% rate of the government’s MSME credit program. The same study by Flaminiano and Francisco (2019) showed that 47% of small and medium sized enterprises in their sample obtained loans from informal sources.

...

An estimate by the International finance Corporation (2017) showed that MSMEs in the Philippines are facing a financing gap of USD 221.8 billion. This figure is equivalent to 76% of the country’s GDP, the largest gap among the 128 countries surveyed in the IFC report. (Nomura, 2020)

The informal lenders don’t print money, that’s the role of the banks, and the BSP.

Simply, the Nomura study didn’t say where creditors of the informal market obtained their resources: Our supposition: aside from personal savings, 5-6 operators and their ilk may be engaged in credit arbitrage or borrow (low interest) from the banking system, and lend (high interest) to the MSMEs—virtually a bank business model—except that they don’t take in deposits.

The fact that despite the intensive policy challenges, a thriving MSME translates a resilient informal credit arbitrage market—yes, these are part of the shadow banking system.

As an aside, uncollateralized 5-6 lending is indeed a very risky business: collections from borrowers through staggered payments occur daily, accompanied by high default rates, which explains the elevated interest rates.

Figure 3

That is to say, the shadow banks or black markets in credit, fill the vacuum or the humungous financing gap posed by the inadequacy of the formal financial sector. (Figure 3, upper diagram)

The financing gap may be smaller today—partly due to digitalization of transactional platforms—but it still remains significant.

This also indicates that published leverage understates the actual leverage in both the financial system and the economy.

Intriguingly, unlike the pre-2019 era, there has been barely any media coverage of the shadow banking system—as if it no longer exists.

As a caveat, shadow banking "involves financial activities, mainly lending, undertaken by non-banks and entities not regulated by the BSP," which implies that even formal institutions may be engaged in "unregulated activities."

Remember when the former President expressed his desire to crack down on 5-6 lending, vowing to "kill the loan sharks," in 2019?

If such a crackdown had succeeded, it could have collapsed the economy. So, it’s no surprise that the attempt to crush the informal economy eventually faded into oblivion.

The fact that informal credit survived and has grown despite the unfavorable political circumstances indicates that the suppressed lending to MSMEs has barely been about the trade-off between risk and reward.

It wasn’t risk that has stymied bank lending to MSMEs, but politics (for example, the artificial suppression of interest rates to reflect risk profiles).

More below.

Has the media and its experts informed you about this?

Still, this highlights the chronic distributional flaws of GDP: it doesn’t reflect the average experience but is instead skewed toward those who benefit from the skewed political policies.

In any case, mainstream media and its experts tend to focus on benchmarks like GDP rather than reporting on the deeper structural dynamics of the economy.

V. Deepening Thrust Towards Banking Monopolization: Rising Risks to Financial System Stability

Three, if banks have lent less to MSMEs, then who constituted the core of borrowers?

Naturally, these were the firms of elites (including bank borrowings), the consumers from the "banked" middle and upper classes, and the government.

Total Financial Resources (TFR) reached an all-time high of Php 32.8 trillion as of October, accounting for about 147% and 123% of the estimated real and headline GDP for 2024, respectively. (Figure 3, lower pane)

TFR represents gross assets based on the Financial Reporting Package (FRP) of banking and non-bank financial institutions, which includes their loan portfolios.

The banking system’s share of TFR stood at 83.2% last October, marking the second-highest level, slightly below September’s record of 83.3%. Meanwhile, Universal-Commercial banks accounted for 77.8% of the banking system’s share in October, marginally down from their record 78% in September.

These figures reveal that the banking system has been outpacing the asset growth of the non-banking sector, thereby increasing its share and deepening its concentration.

Simultaneously, Universal-Commercial banks have been driving the banking system’s growing dominance in TFR.

The significance of this lies in the current supply-side dynamic, which points towards a trajectory of virtual monopolization within the financial system. As a result, this trend also magnifies concentration risk.

VI. How PSEi 30's Debt Dynamics Affect MSME Struggles

From the demand side, the 9-month debt of the non-financial components of the PSEi 30 reached Php 5.52 trillion, the second-highest level, trailing only the all-time high in 2022. However, its share of TFR and nominal GDP has declined from 17.7% and 30.8% in 2023 to 16.7% and 29.3% in 2024.

Figure 4

Over the past two years, the PSEi 30's share of debt relative to TFR and nominal GDP has steadily decreased. (Figure 4, upper chart)

It is worth noting that the 9-month PSEi 30 revenues-to-nominal GDP ratio remained nearly unchanged from 2023 at 27.9%, representing the second-highest level since at least 2020. (Figure 4, lower image)

Thus, the activities of PSEi 30 composite members alone account for a substantial share of economic and financial activity, a figure that would be further amplified by the broader universe of listed stocks on the PSE.

Nevertheless, their declining share, alongside rising TFR, indicates an increase in credit absorption by ex-PSEi and unlisted firms.

VII. The Impact of Bank Borrowings and Government Debt Financing on MSMEs’ Challenges

Figure 5

On the other hand, bank borrowings declined from a record high of Php 1.7 trillion (49.7% YoY) in September to Php 1.6 trillion (41.34% YoY) in October. Due to liquidity concerns, most of these borrowings have been concentrated in T-bills. (Figure 5, topmost visual)

As it happens, Philippine lenders, as borrowers, also compete with their clients for the public’s savings.

Meanwhile, the banking system’s net claims on the central government (NCoCG) expanded by 8.3% to Php 5.13 trillion as of October.

The BSP defines Net Claims on Central Government as including "domestic securities issued by and loans and advances extended to the CG, net of liabilities to the CG such as deposits."

In October, the banks' NCoCG accounted for approximately 23% of nominal GDP (NGDP), 18% of headline GDP, and 15.6% of the period’s TFR.

Furthermore, bank consumer lending, including real estate loans, reached a record high of Php 2.92 trillion in Q3, supported by an unprecedented 22% share of the sector’s record loan portfolio, which totaled Php 13.24 trillion. (Figure 4, middle graph)

Concomitantly, the banking system’s Held-to-Maturity (HTM) assets stood at nearly Php 3.99 trillion in October, just shy of the all-time high of Php 4.02 trillion recorded in December 2023. Notably, NCoCG accounted for 128.6% of HTM assets. HTM assets also represented 15.1% of the banking system’s total asset base of Php 26.41 trillion. (Figure 4, bottom chart)

This means the bank’s portfolio has been brimming with loans to the government, which have been concealed through their HTM holdings.

Figure 6

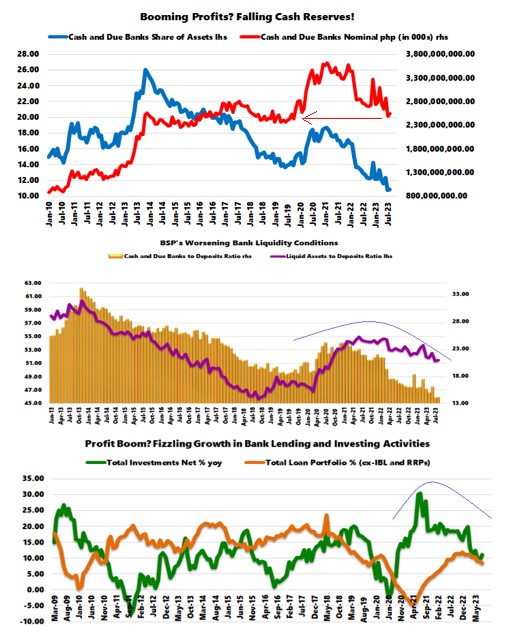

Alongside non-performing loans (NPLs), these factors have contributed to the draining of the industry’s liquidity. Despite the June 2023 RRR cuts and the 2024 easing cycle (interest rate cuts), the BSP's measures of liquidity—cash-to-deposits and liquid assets-to-deposits—remain on a downward trend. (Figure 6, upper window)

VIII. How Trickle-Down Economics and the Crowding Out Effect Stifle MSME Growth

It is not just the banking system; the government has also been absorbing financial resources from non-banking institutions (Other Financial Corporations), which amounted to Php 2.34 trillion in Q2 (+11.1% YoY)—the second highest on record. (Figure 6, lower graph)

These figures reveal a fundamental political dimension behind the lagging bank lending performance to MSMEs: the "trickle-down" theory of economic development and the "crowding-out" syndrome affecting credit distribution.

The banking industry not only lends heavily to the government—reducing credit availability for MSMEs—but also allocates massive amounts of financial resources to institutions closely tied to the government.

This is evident by capital market borrowings by the banking system, as well as bank lending and capital market financing and bank borrowings by PSE firms.

A clear example is San Miguel Corporation's staggering Q3 2024 debt of Php 1.477 trillion, where it is reasonable to assume that local banks hold a significant portion of the credit exposure.

The repercussions, as noted, are significant:

Its opportunity costs translate into either productive lending to the broader economy or financing competitiveness among SMEs (Prudent Investor, December 2024)

Finally, in addition to the above, MSMEs face further challenges from the "inflation tax," an increasing number of administrative regulations (such as minimum wage policies that disproportionately disadvantage MSMEs while favoring elites), and burdensome (direct) taxes.

IX. Conclusion: The Magna Carta for MSMEs Represents a "Symbolic Law," Possible Solutions to Promote Inclusive MSME Growth

Ultimately, the ideology-driven "trickle-down" theory has underpinned the political-economic framework, where government spending, in tandem with elite interests, anchors economic development.

Within this context, the Magna Carta for MSMEs stands as a "Symbolic Law" or "Unenforced Law"—where legislation "exists primarily for symbolic purposes, with little to no intention of actual enforcement."

Politically, a likely short-term populist response would be to demand substantial increases in penalty rates for non-compliance (to punitive levels, perhaps tied to a fraction of total bank assets). However, this approach would likely trigger numerous unintended consequences, including heightened corruption, reduced transparency, higher lending rates, and more.

Moreover, with the top hierarchy of the BSP populated by banking officials, this scenario is unlikely to materialize. There will be no demand for such measures because only a few are aware of the underlying issues.

While the solution to this problem is undoubtedly complex, we suggest the following:

1 Reduce government spending: Roll back government expenditures to pre-pandemic levels and ensure minimal growth in spending.

2 Let markets set interest rates: Allow interest rates to reflect actual risks rather than artificially suppressing them.

3 Address the debt overhang through market mechanisms: Let markets resolve the current debt burden instead of propping it up with unsustainable liquidity injections and credit expansions by both the banking system and the BSP.

4 Liberalize the economy: Enable greater economic and market liberalization to reflect true economic conditions.

5 Adopt a combination of the above approaches.

The mainstream approach to resolving the current economic dilemma, however, remains rooted in a consequentialist political scheme—where "the end justifies the means."

This mindset often prioritizes benchmarks and virtue signaling in the supposed pursuit of MSME welfare. For example, the establishment of a credit risk database for MSMEs is presently touted as a solution.

While such measures may yield marginal gains, they are unlikely to address the root issues for the reasons outlined above.

_____

References

Republic Act 5901: Guide to the Magna Carta for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (RA 6977, as amended by RA 8289, and further amended by RA 9501), p.17 SME Finance Forum

Margarito Teves and Griselda Santos, MSME Financing in the Philippines: Status, Challenges and Opportunities, 2020 p.16 Nomura Foundation

Prudent Investor, Is

San Miguel’s Ever-Growing Debt the "Sword of Damocles" Hanging over

the Philippine Economy and the PSE? December 02, 2024