In this issue

A Rescue, Not a Stimulus:

BSP’s June Cut and the Banking System’s Liquidity Crunch

I. Policy Easing in

Question: Credit Concentration and Economic Disparity

II. Elite Concentration:

The Moody's Warning and Its Missing Pieces

III. Why the Elite Bias? Financial

Regulation, Market Concentration and Underlying Incentives

IV. Market Rebellion: When

Reality Defies Policy

V. The Banking System

Under Stress: Evidence of a Rescue Operation

A. Liquidity Deterioration

Despite RRR Cuts

B. Cash Crunch Intensifies

C. Deposit Growth Slowdown

D. Loan Portfolio

Dynamics: Warning Signs Emerge

E. Investment Portfolio

Under Pressure

F. The Liquidity Drain:

Government's Role

G. Monetary Aggregates: Emerging

Disconnection

H. Banking Sector

Adjustments: Borrowings and Repos

I. The NPL Question: Are We Seeing the Full

Picture?

J. The Crowding Out Effect

VI. Conclusion: The Inevitable Reckoning

A Rescue, Not a Stimulus: BSP’s June Cut and the Banking System’s Liquidity Crunch

Despite easing measures, liquidity has tightened, markets have diverged, and systemic risks have deepened across the Philippine banking system.

I. Policy Easing in Question: Credit Concentration and Economic Disparity

The BSP implemented the next phase of its ‘easing cycle’—now comprising four policy rate cuts and two reductions in the reserve requirement ratio (RRR)—complemented by the doubling of deposit insurance coverage.

The question is: to whose benefit?

Is it the general economy?

Bank loans to MSMEs, which are supposedly a target of inclusive growth, require a lending mandate and still accounted for only 4.9% of the banking system’s total loan portfolio as of Q4 2024. This is despite the fact that, according to the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), MSMEs represented 99.6% of total enterprises and employed 66.97% of the workforce in 2023.

In contrast, loans to PSEi 30 non-financial corporations reached Php 5.87 trillion in Q1 2025—equivalent to 17% of the country’s total financial resources.

Public borrowing has also surged to an all-time high of Php 16.752 trillion as of April.

Taken together, total systemic leverage—defined as the sum of bank loans and government debt—reached a record Php 30.825 trillion, or approximately 116% of nominal 2024 GDP.

While bank operations have expanded, fueled by consumer debt, only a minority of Filipinos—those classified as “banked” in the BSP’s financial inclusion survey—reap the benefits. The majority remain excluded from the financial system, limiting the broader economic impact of the BSP’s policies.

The reliance on consumer debt to drive bank growth further concentrates financial resources among a privileged few.

II. Elite Concentration: The Moody's Warning and Its Missing Pieces

On June 21, 2025, Inquirer.net cited Moody’s Ratings:

"In a commentary, Moody’s Ratings said that while conglomerate shareholders have helped boost the balance sheet and loan portfolio of banks by providing capital and corporate lending opportunities, such a tight relationship also increases related-party risks. The global debt watcher also noted how Philippine companies remain highly dependent on banks for funding in the absence of a deep capital market. This, Moody’s said, could become a problem for lenders if corporate borrowers were to struggle to pay their debts during moments of economic downturn." (bold added)

Moody’s commentary touches on contagion risks in a downturn but fails to elaborate on an equally pressing issue: the structural instability caused by deepening credit dependency and growing concentration risks. These may not only emerge during a downturn—they may be the very triggers of one.

The creditor-borrower interdependence between banks and elite-owned corporations reflects a tightly coupled system where benefits, risks, and vulnerabilities are shared. It’s a fallacy to assume one side enjoys the gains while the other bears the risks.

As J. Paul Getty aptly put it:

"If you owe the bank $100, that's your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that's the bank's problem."

In practice, this means banks are more likely to continue lending to credit-stressed conglomerates than force defaults, further entrenching financial fragility.

What’s missing in most mainstream commentary is the causal question: Why have lending ties deepened so disproportionately between banks and elite-owned firms, rather than being broadly distributed across the economy?

The answer lies in institutional incentives rooted in the political regime.

As discussed in 2019, the BSP’s trickle-down easy money regime played a key role in enabling Jollibee’s “Pacman strategy”—a debt-financed spree of horizontal expansion through competitor acquisitions.

III. Why the Elite Bias? Financial Regulation, Market Concentration and Underlying Incentives

Moreover, regulatory actions appear to favor elite interests.

On June 17, 2025, ABS-CBN reported:

"In a statement, the SEC said the licenses [of over 400 lending companies] were revoked for failing to file their audited financial statements, general information sheet, director or trustee compensation report, and director or trustee appraisal or performance report and the standards or criteria for the assessment."

Could this reflect regulatory overreach aimed at eliminating competition favoring elite-controlled financial institutions? Is the SEC becoming a tacit ‘hatchet man’ serving oligopolistic interests via arbitrary technicalities?

Philippine banks—particularly Universal Commercial banks—now control a staggering 82.64% of the financial system’s total resources and 77.08% of all financial assets (as of April 2025).

Aside from BSP liquidity and bureaucratic advantages, political factors such as ‘regulatory capture’ and the ‘revolving door’ politics further entrench elite power.

Many senior officials at the BSP and across the government are former bank executives, billionaires and their appointees, or close associates. Thus, instead of striving for the Benthamite utilitarian principle of “greatest good for the greatest number,” agencies may instead pursue policies aligned with powerful vested interests.

This brings us back to the rate cuts: while framed as pro-growth, they largely serve to ease the cost of servicing a mountain of debt owed by government, conglomerates, and elite-controlled banks.

Figure 1

However, its impact on average Filipinos remains negligible, with official statistics increasingly revealing the diminishing returns of these policies.

The BSP’s rate and RRR cuts, coming amid a surge in UC bank lending, risk undermining GDP momentum (Figure 1)

IV. Market Rebellion: When Reality Defies Policy

Even markets appear to be revolting against the BSP's policies!

Figure 2

Despite plunging Consumer Price Index (CPI) figures, Treasury bill rates, which should reflect the BSP's actions, have barely followed the easing cycle. (Figure 2, topmost window)

Yields of Philippine bonds (10, 20, and 25 years) have been rising since October 2024 reinforcing the 2020 uptrend! (Figure 2, middle image)

Inflation risks continue to be manifested by the bearish

steepening slope of the Philippine Treasury yield curve. (Figure 2, lower graph)

Figure 3

Additionally, the USD/PHP exchange rate sharply rebounded even before the BSP announcement. (Figure 3, topmost diagram)

Treasury yields and the USD/PHP have fundamentally ignored the government's CPI data and the BSP's easing policies.

Importantly, elevated T-bill rates likely reflect liquidity pressures, while rising bond yields signal mounting fiscal concerns combined with rising inflation risks.

Strikingly, because Treasury bond yields remain elevated despite declining CPI, the average monthly bank lending rates remain close to recent highs despite the BSP's easing measures! (Figure 3, middle chart)

While this developing divergence has been ignored or glossed over by the consensus, it highlights a worrisome imbalance that authorities seem to be masking through various forms of interventions or "benchmark-ism" channeled through market manipulation, price controls, and statistical inflation.

V. The Banking System Under Stress: Evidence of a Rescue Operation

We have been constantly monitoring the banking system and can only conclude that the BSP easing cycle appears to be a dramatic effort to rescue the banking system.

A. Liquidity Deterioration Despite RRR Cuts

Astonishingly, within a month after the RRR cuts, bank liquidity conditions deteriorated further:

·

Cash and Due Banks-to-Deposit Ratio

dropped from 10.37% in March to 9.68% in April—a milestone low

· Liquid Assets-to-Deposit Ratio plunged from 49.5% in March to 48.3% in April—its lowest level since March 2020

Liquid assets consist of the sum of cash and due banks plus Net Financial assets (net of equity investments). Fundamentally, both indicators show the extinguishment of the BSP's historic pandemic recession stimulus. (Figure 3, lowest window)

B. Cash Crunch Intensifies

Figure 4

Year-over-year change of Cash and Due Banks crashed by 24.75% to Php 1.914 trillion—its lowest level since at least 2014. Despite the Php 429.4 billion of bank funds released to the banking system from the October 2024 and March 2025 RRR cuts, bank liquidity has been draining rapidly. (Figure 4, topmost visual)

C. Deposit Growth Slowdown

The liquidity crunch in the banking system appears to be spreading.

The sharp slowdown has been manifested through deposit liabilities, where year-over-year growth decelerated from 5.42% in March to 4.04% in April due to materially slowing peso and foreign exchange deposits, which grew by 5.9% and 3.23% in March to 4.6% and 1.6% in April respectively. (Figure 4, middle image)

D. Loan Portfolio Dynamics: Warning Signs Emerge

Led by Universal-Commercial banks, growth of the banking system's total loan portfolio slowed from 12.6% in March to 12.2% in April. UC banks posted a deceleration from 12.36% year-over-year growth in March to 11.85% in April.

However, the banking system's balance sheet revealed a unmistakable divergence: the rapid deceleration of loan growth. Growth of the Total Loan Portfolio (TLP), inclusive of interbank lending (IBL) and Reverse Repurchase (RRP) agreements, plunged from 14.5% in March to 10.21% in April, reaching Php 14.845 trillion. (Figure 4, lowest graph)

This dramatic drop in TLP growth contributed significantly to the steep decline in deposit growth.

E. Investment Portfolio Under Pressure

Figure 5

Banks' total investments have likewise materially slowed, easing from 11.95% in March to 8.84% in April. While Held-to-Maturity (HTM) securities growth slowed 0.58% month-over-month, they were up 0.98% year-over-year.

Held-for-Trading (HFT) assets posted the largest growth drop, from 79% in March to 25% in April.

Meanwhile, accumulated market losses eased from Php 21 billion in March to Php 19.6 billion in May. (Figure 5, topmost graph)

Rising bond yields should continue to pressure bank trading assets, with emphasis on HTMs, which accounted for 52.7% of Gross Financial Assets in May.

A widening fiscal deficit will likely prompt banks to increase support for government treasury issuances—creating a feedback loop that should contribute to rising bond yields.

F. The Liquidity Drain: Government's Role

Part of the liquidity pressures stem from the BSP's reduction in its net claims on the central government (NCoCG) as it wound down pandemic-era financing.

Simultaneously, the recent buildup in government deposits at the BSP—reflecting the Treasury's record borrowing—has further absorbed liquidity from the banking system. (Figure 5, middle image)

G. Monetary Aggregates: Emerging Disconnection

Despite the BSP's easing measures, emerging pressures on bank lending and investment assets, manifested through a cash drain and slowing deposits, have resulted in a sharp decrease in the net asset growth of the Philippine banking system. Year-over-year growth of net assets slackened from 7.8% in April to 5.5% in May. (Figure 5, lowest chart)

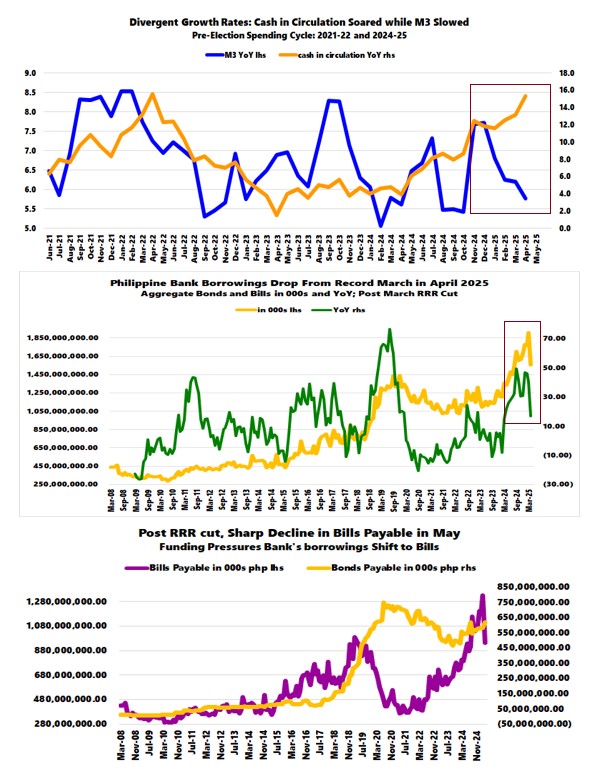

Figure 6

Interestingly, despite the cash-in-circulation boost related to May's midterm election spending—which hit a growth rate of 15.4% in April (an all-time high in peso terms), just slightly off the 15.5% recorded during the 2022 Presidential elections—M3 growth sharply slowed from 6.2% in March to 5.8% in April and has diverged from cash growth since December 2024. (Figure 6, topmost window)

The sharp decline in M2 growth—from 6.6% in April to 6.0% in May—reflecting the drastic slowdown in savings and time deposits from 5.5% and 7.6% in April to 4.5% and 5.8% in May respectively, demonstrates the spillover effects of the liquidity crunch experienced by the Philippine banking system.

H. Banking Sector Adjustments: Borrowings and Repos

Nonetheless, probably because of the RRR cuts, aggregate year-over-year growth of bank borrowings decreased steeply from 40.3% to 16.93% over the same period. (Figure 6, middle graph)

Likely drawing from cash reserves and the infusion from RRR cuts, bills payable fell from Php 1.328 trillion to Php 941.6 billion, while bonds rose from Php 578.8 billion to Php 616.744 billion. (Figure 6, lowest diagram)

Banks' reverse repo transactions with the BSP plunged by 51.22% while increasing 30.8% with other banks.

As we recently tweeted, banks appear to have resumed their flurry of borrowing activity in the capital markets this June.

I. The NPL Question: Are We Seeing the Full Picture?

While credit delinquencies expressed via Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) have recently been marginally higher in May, the ongoing liquidity crunch cannot be directly attributed to them—unless the BSP and banks have been massively understating these figures, which we suspect they are.

J. The Crowding Out Effect

Bank borrowings from capital markets amplify the "crowding-out effect" amid growing competition between government debt and elite conglomerates' credit needs.

The government’s significant role in the financial system further complicates this dynamic, as it absorbs liquidity through record borrowing.

Or, it would be incomplete to examine banks' relationships with elite-owned corporations without acknowledging the government's significant role in the financial system.

VI. Conclusion: The Inevitable Reckoning

The deepening divergent performance between markets and government policies highlights not only the tension between markets and statistics but, more importantly, the progressing friction between economic and financial policies and the underlying economy.

Is the consensus bereft of understanding, or are they attempting to bury the logical precept that greater concentration of credit activities leads to higher counterparty and contagion risks? Will this Overton Window prevent the inevitable reckoning?

The evidence suggests that the BSP's easing cycle, rather than supporting broad-based economic growth, primarily serves to maintain the stability of an increasingly fragile financial system that disproportionately benefits elite interests.

With authorities reporting May’s fiscal conditions last week (to be discussed in the next issue), we may soon witness how this divergence could trigger significant volatility or even systemic instability

The question is not whether this system is

sustainable—the data clearly indicates it is not—but rather how long political

and regulatory interventions can delay the inevitable correction, and at what

cost to the broader Philippine economy.