When you net out all the assets and liabilities in the economy, the only thing that remains is our stock of productive investments, inventions, education, organizational structures, and unconsumed natural resources. Those are the basis of our national wealth—Dr. John P. Hussman

In this issue

The Seen, the Unseen, and

the Taxed: CMEPA as Financial Repression by Design

I. Reform as Spectacle:

Bastiat’s Warning and the Mask of Inclusion

II. What is Seen: Promises

of Efficiency and Modernization

III. The Unseen: How CMEPA

Undermines the Socio-Political Economy

Theme 1: Taxing Savings, Undermining Capital Formation

Theme 2: Systemic Financial Risks and Policy Incoherence

Theme 3: Fiscal Extraction, the Wealth Effect and the Political

Economy

Theme 4: Institutional and Socio-Political Deterioration

IV. Conclusion: CMEPA—A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: Behavioral Reprogramming and the Unseen Costs of Reform

The Seen, the Unseen, and the Taxed: CMEPA as Financial Repression by Design

A wolf in sheep’s clothing: A policy not only distorting capital markets but reprogramming society toward short-termism, volatility, and fragility.

I. Reform as Spectacle: From Rhetoric to Repercussion—CMEPA Through Bastiat’s Eyes

All legislation arrives adorned in rhetoric—its presentation aimed to evoke public trust and collective good. Much like Potemkin villages, reforms such as CMEPA appear to serve Jeremy Bentham’s ‘greater good,’ yet beneath the façade lies the concealed agenda of entrenched interests.

Echoing Frédéric Bastiat’s indispensable insight, we must learn to discern between what is seen and what is unseen.

However, the difference between these is huge, for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. From which it follows that a bad Economist will pursue a small current benefit that is followed by a large disadvantage in the future, while a true Economist will pursue a large benefit in the future at the risk of suffering a small disadvantage immediately" (Bastiat, 1850) [bold added]

With this lens, we examine the Capital Markets Efficiency Promotion Act (CMEPA)—Republic Act No. 12214, enacted on May 29, 2025, effective July 1.

II. What is Seen: Promises of Efficiency and Modernization

CMEPA has been billed as a modernization effort to deepen financial markets and enhance participation. Its measures include:

- A flat 20% tax on passive income, including interest from long-term deposits and peso bonds

- Reduced stock transaction tax (STT) to 0.1%

- Expanded definition of “securities” to widen taxable instruments

- Removal of exemptions for GOCCs and long-term depositors, while retaining perks for FCDUs and lottery bettors

Portrayed as a reform designed to streamline taxation and deepen the capital markets, CMEPA hides a more troubling reality beneath its glitter. It reveals a policy that taxes the foundations of financial stability and long-term capital formation. While it reduces transaction taxes and simplifies some rates, its deeper impact is a radical shift in how the Philippine state attempts to influence public mindset and choices—how it allocates risk, treats saving, and commandeers private resources.

III. The Unseen: How CMEPA Undermines the Socio-Political Economy

This critique identifies several thematic consequences:

Theme 1: Taxing Savings, Undermining Capital Formation

Figure/Table 1

1 Flattening Tax Across All Maturities

The new 20% final withholding tax (FWT) rate now applies across all maturities, including long-term deposits and investment instruments previously exempted. (Figure/Table 1)

Retail savers and retirees, dependent on deposit-based income, now face disincentives for capital preservation. Long-term financial instruments lose their privileged status, undermining capital formation.

2 Financial Repression by Design

Moreover, savings and capital are diverted from productive sectors to fund fiscal deficits, choking investment and inviting misallocation.

3 Regressive Impact on Small Savers

The uniform tax rate applies regardless of investor profile. Small savers and retirees lose disproportionately. Meanwhile, the wealthy retain flexibility—shifting funds offshore or into tax-exempt alternatives.

4 Deepening the Savings-Investment Divide

CMEPA taxes the engine of investment—savings—while encouraging speculative behavior. As domestic savings weaken, investment becomes more reliant on volatile international capital flows and risky leveraging, heightening systemic vulnerability.

Theme 2: Systemic Financial Risks and Policy Incoherence

5 Balance Sheet Mismatches

CMEPA induces short-term liabilities against long-term assets, eroding liquidity buffers. Banks stretch to meet Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) thresholds while chasing yield in speculative sectors—real estate, retail, accommodation, construction.

FX funding stability worsens as offshore placements rise, increasing currency mismatch risk for entities with dollar-denominated obligations.

This weakens the stability of the banking system.

6 Weaker Bank Profitability and Liquidity

Banks face tighter net interest margins, especially as liabilities are taxed while fixed-yield assets remain unchanged. Asset durations can’t adjust as quickly as funding costs, intensifying balance sheet compression undermining liquidity.

Combined with BSP’s RRR cuts and other easing, this suggests rising liquidity stress rather than financial deepening.

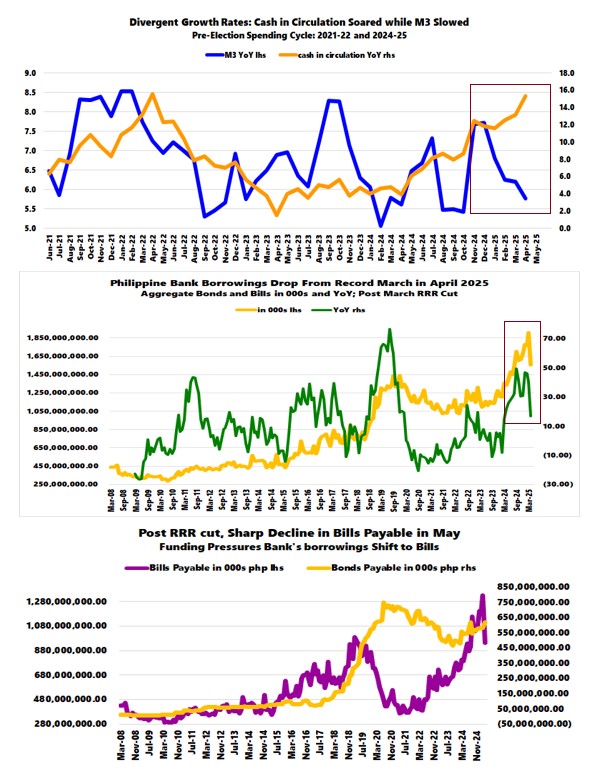

Figure 2

The weakened deposit base—as revealed by the downtrend in the growth of deposit liabilities—partly explains the doubling of deposit insurance in March, a reactive gesture to rising liquidity risk. Notably, the slowdown appears to have accelerated in 2025. (Figure 2)

Figure 3

But it is not just deposits: the decline in cash and

liquid assets—as shown by falling cash-to-deposit and liquid assets-to-deposit

ratios—highlights the mounting fragility of bank conditions. (Figure 3)

Figure 4

The law compounds the fragile cash position of Philippine banks, redistributing liquidity into riskier corners of the balance sheet.

7 Systemic Leverage Risk

Taxing interest income inflates debt servicing costs, worsening liquidity stress across sectors already burdened with leverage. The gap between savings returns and borrowing costs widens, deepening household and corporate fragility.

8 Undermining Financial Deepening

Instead of encouraging broader access to financial instruments, the reform may drive savers toward informal systems, offshore accounts, or speculative assets—increasing volatility and disintermediation.

9 Incoherence with Monetary Policy

When interest income is taxed heavily, monetary policy transmission weakens. A rate hike meant to incentivize saving may be neutralized by post-tax returns that remain unattractive. This creates friction between fiscal and monetary authorities.

10 Disincentivizing Long-Term Domestic Funding

Removing exemptions from long-duration peso instruments weakens the domestic funding base. The government may respond by issuing shorter-tenor bonds, amplifying rollover risk—particularly amid widening deficits.

Theme 3: Fiscal Extraction, the Wealth Effect and the Political Economy

11 From Market-Based to

Tax-Based Government Financing

Figure 5

CMEPA shifts the state's financing strategy from indirect borrowing (via banks' net claims on government) to direct taxation of interest income. This reduces the role of market-based funding and deepens reliance on financial repression. (Figure 5)

Philippine banks have long underwritten the government’s historic deficit spending. But with deposits eroding and liquidity thinning, can CMEPA’s pivot toward direct taxation rebalance this dynamic—or will banks be forced to sustain an inflationary financing regime they may no longer afford?

12 Crowding Out, Capital Misallocation, and Short-Termism

Taxing savings redirects capital from private to public use. Outside of government, the investment community is pushed toward velocity over duration, incentivizing speculative short-term returns rather than productive long-term investments. This leads to boom-bust cycles that consume capital and savings, ultimately lowering the standard of living for the average citizen.

13 Reform Signals to Mask Fiscal Strain

14 Wealth-Effect Ideology and Speculative Diversion

DOF claims that CMEPA will "diversify income sources," implicitly inviting or encouraging ordinary Filipinos to engage in asset (stock and real estate) speculation.

The BSP’s inflated real estate index, as discussed last week, aligns perfectly with this narrative.

Yet if savings have weakened, with what are people supposed to speculate?

In essence, the law encourages speculative behavior over productive undertakings—gambling on the trickle-down “easy money”-fueled wealth effect to stimulate growth.

Theme 4: Institutional and Socio-Political Deterioration

15 Favoring Non-Depository Institutions and Digital Control

With capital markets shallow, the government’s pivot appears aimed at stock and real estate price inflation to support GDP optics.

But there might be more to this: could the erosion of savings-based intermediation serve as a stepping-stone—or perhaps a gauntlet—to the advent of a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) regime?

16 Widening Inequality

As savings erode and productive investment slows, the burden of taxation and financial volatility falls hardest on low- and middle-income households. Elites with offshore access or alternative vehicles thrive—amplifying the wealth gap.

17 Capital Consumption and the Attack on Private Property

CMEPA’s redistributive logic undermines the sanctity of private property. Through financial repression, taxation, and inflation, it transforms capital into consumption, violating the very principles of long-term economic development.

18 Behavioral Reprogramming Toward Short-Termism

CMEPA reorients household and institutional incentives by elevating time preferences, nudging actors toward short-term consumption and speculative tendencies. The long-term result encompasses not only economic and financial dimensions, but also social, political, and cultural shifts away from prudence.

19 Increased State Power and Erosion of Economic and Civil Liberties

20 Desperation, Not Reform

Beneath the reformist language lies the scent of desperation. As government spending outpaces revenues and "free lunch" policies proliferate, the state appears increasingly willing to extract resources wherever possible, even at the cost of long-term economic damage.

CMEPA may be seen less as a policy of modernization and more as a pretext to justify a broader power grab for control over the nation’s remaining financial surpluses. Such fiscal maneuvers reveal a growing reliance on coercive tools to finance political programs and preserve power.

IV. Conclusion: CMEPA—A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: Behavioral Reprogramming and the Unseen Costs of Reform

CMEPA is not neutral.

It is policy with intent—velocity over virtue, spectacle over substance. Beneath its reformist gloss lies a deliberate reordering of incentives: a behavioral reprogramming that elevates time preference across households, businesses, banks, and the state itself.

The ramifications are profound. As savings erode, the economy pivots toward a spend-and-speculate framework, exposing malinvestments and shortening planning horizons. Bank balance sheets tilt toward short-duration, high-risk assets. Businesses recalibrate toward immediacy, while regulatory structures and political priorities—including education—subtly shift to accommodate the new paradigm: favoring current events over historical depth, short-term fixes over long-term resilience.

As immediacy becomes institutionalized, political incentives may shift as well—gravitating toward authoritarian tendencies, where centralized authority and executive expedience increasingly replace civic pluralism.

This drift accelerates leverage and volatility. Coupled with BSP’s easy money, fiscal splurging, deepening economic concentration, the entrenching of the “build and they will come” paradigm, benchmark-ism, and the subtle embrace of a war economy—where economic centralization and speculative asset inflation substitute for organic growth—the system veers toward the bust phase of a boom-bust cycle.

CMEPA, dressed in reformist language, delivers structural inversion through a reordering of incentives—substituting short-term economic activity for long-term capital formation. It penalizes saving, rewards speculation, and manufactures stability to perform confidence. Its impact is philosophical as much as economic: undermining the sanctity of private property and sabotaging the long-term architecture of capital.

As Ludwig von Mises warned:

Saving, capital accumulation, is the agency that has transformed step-by-step the awkward search for food on the part of savage cave dwellers into the modern ways of industry. The pacemakers of this evolution were the ideas that created the institutional framework within which capital accumulation was rendered safe by the principle of private ownership of the means of production. Every step forward on the way toward prosperity is the effect of saving. The most ingenious technological inventions would be practically useless if the capital goods required for their utilization had not been accumulated by saving. (Mises, 1956)

The unseen consequences of policy often outweigh the visible promises, as Bastiat warned us.

CMEPA’s structural tax changes reprogram public incentives in ways that may appear benign, but will likely unleash instability, fragility, and misallocation—outcomes not immediately visible, but deeply consequential.

Unless reversed, CMEPA’s legacy will be one of hollowed market and social institutions, increased fragility of public governance, and ultimately, social unraveling—where the erosion of savings and stability gives way to volatility, inequality, and the breakdown of trust in both economic and civic life.

CMEPA is a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

____

References:

Frédéric Bastiat What is Seen and What is Not Seen, or Political Economy in One Lesson [July 1850], https://oll.libertyfund.org/

Ludwig von Mises, The

ANTI-CAPITALISTIC MENTALITY, p 39, D. VAN NOSTRAND COMPANY (Canada), LTD

1956, Mises Institute 2008, Mises.org