There are people who know a fair amount, or even a great deal, about economics. To know a lot about economics, however, is not to know economics; it’s not to know how to think like an economist.Someone who knows a lot about economics has learned a lot of economic jargon (e.g., “marginal cost”) and all of the textbook definitions (e.g., “Marginal cost is the addition to the producer’s total cost of producing one additional unit of output”). This person also has memorized the often-intricate rules for how to bend and shift various ‘curves’ such as supply, demand, cost, and IS-LM. And, today, this person is often also skilled at finding quantitative data and processing them in the various data-processing machines that are called econometric techniques.Knowing how to think productively like an economist is typically assisted by knowledge of such things, but it involves far more than knowing the above. Indeed, knowing the above isn’t as essential as the typical economist today supposes it is to being a genuinely good economist. Too often, mastery of superficial stuff such as the above convinces those who have mastered these superficialities that they understand economics. The sorry result is that such people never bother to master the skills of actually doing economic analysis properly.Imagine someone who memorizes a world-class cookbook. This person learns all the culinary jargon; all the formulae for all the soups and sauces; all the best combinations of spices; all the recommended oven temperatures for all the different baked dishes. All the recipes and information printed in the cookbook. But what this person really ‘learns’ from the cookbook is that preparing meals is an engineering feat: faithfully follow the recipes of the ‘best’ cookbooks and you can be a superb cook. Voila! Cooking is easy if one masters the recipes!What this cookbook student never learns, though, is that being a superb cook ultimately requires individual judgment, wisdom, and creativity in knowing when to stick with a recipe and when sticking with a recipe will produce a meal unfit for tonight’s dinner guests. What this cookbook student never learns is how to create delicious meals for which there is no already-printed recipe. This cookbook student, in short, masters, at best, only that which a skilled chef can explicitly commit to paper; this cookbook student – being in fact quite dull – never masters the creative art of cooking.Lots of economists, in my view, are like this dull cookbook memorizer. They sling the jargon freely; they know, and can recite flawlessly, all the latest recipes (that is, models). They can name those recipes’ creators (that is, today’s in-vogue economic theorists). They know a lot about economics.But when they actually attempt to do economics, it quickly becomes clear that they don’t know what they’re doing. They’re not really economists. They consistently fail to ask that most important of all questions that economists ask: “As compared to what?” They forget that monetary costs and monetary benefits are only a subset (and sometimes a small subset) of full costs and benefits: They mistakenly suppose that monetary costs and benefits are all of the relevant costs and benefits. They, in the most wooden of ways, take the recipes they know literally: Any observed real-world variations from the cookbook (that is, textbook) recipes are, for such economists, solid evidence that the real-world is flawed.The fact that reality is far richer in details – the fact that competition operates on many more margins than are included in economists’ formal models – the fact that people, as consumers and as producers, are indescribably more creative and clever and intrepid and diverse than are the ‘agents’ who populate economic models – the fact that maximizing the collective monetary incomes of some arbitrarily defined group of people (for example, “low-skilled workers” or “blue-eyed people whose last names start with the letter Z”) is likely to be both positively meaningless and normatively dubious – these facts are invisible to too many modern economists. This blindness to the most important features of economic reality is promoted by the failure of modern economic training to teach young economists to ask, always to ask, why.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Tuesday, November 10, 2015

Quote of the Day: The Economics of the Dull Cookbook Memorizer

Tuesday, October 06, 2015

Friday, June 20, 2014

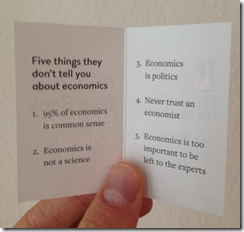

Graphics of the Day: The 5 things they don't tell you about economics

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

Quote of the Day: On the Denial of Economics: Reality is not Optiional

Economics has the same ontological status as physics --- reality is not optional --- but the "laws" of economics are derived following different epistemological procedures. This is really nothing more, or less, than what Aristotle taught about methods of analysis being chosen based on appropriateness. Economics is about human action in the face of scarcity. Human purposes and plans permeate the analysis from start to finish. When economics gets derailed --- and folks it often does due to factors such as philosophical fads and fashions, or political expediency in public policy debates --- usually the culprit is one of 3 things: (1) a denial of agent rationality, (2) a denial of scarcity, and (3) a denial of how the price system works to help us cope with scracity by aiding us in the negotion of the trade-offs we all must face. This denial can come in sophisticated form --- e.g., Keynes --- or it can come in an unsophisticated form --- e.g., man on the street. But make no mistake about it, the denial has the same impact on the "laws" of economics as the denial of the "laws" of physics would by a man about to jump off the top of building would on the inevitable impact. All his denials will not mean much when he hits the pavement.

Wednesday, February 06, 2013

Video: Milton Friedman: Only Government Create Inflation

(1:37) Any other attribution to growth in inflation is wrong. Consumers don’t produce it. Producers don’t produce it. Trade unions don’t produce it. Foreign sheiks don’t produce it. Oil imports don’t produce it. What produces it is too much government spending and too much creation of money and nothing else.

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Video: The Economics of Valentine's Day

Happy Valentines Day!

Thursday, September 01, 2011

Asian Capital Markets Likely a Beneficiary of Europe’s High Taxes and Regulatory Maze

“If you tax something, you get less of it”, that’s Professor Mark Perry’s Economics 101

The following should be a great example, from Bloomberg, (bold highlights mine)

Banks in Europe are exploring ways to cut costs by routing more of their trades and other business through overseas subsidiaries, a plan that may shift tax revenue away from London and loosen European regulators’ influence over the lenders.

Nomura Holdings Inc., HSBC Holdings Plc (HSBA) and UBS AG (UBSN) are among lenders preparing plans to book as much business as possible through legal entities in jurisdictions where tax rates are lower and rules on capital and liquidity are less onerous, the banks and lawyers and accountants working with them say.

“Every bank is trying to work out the best way to be structured under the new rules,” Chris Matten, a partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP in Singapore, said in a telephone interview. “It’s not just a question of what activities banks are in. It’s about which entities they put that business through and in which jurisdictions.”

Banks could record as much as 30 percent of the value of their trades through Hong Kong, Singapore and other jurisdictions instead of hubs such as London and New York without running into trouble with regulators, Matten said. Such a move would hurt traditional hubs such as London because assets are treated for tax and regulatory purposes in the country where they are booked. It would also allow banks to sidestep the U.K. bank levy, introduced last year to raise 2.5 billion pounds ($4.1 billion) from lenders operating in Britain, as well as any financial transaction tax imposed by the European Union.

This is one major lesson politicians and their followers can’t seem to digest, absorb or learn.

Nevertheless, this is also one major factor that could drive funds and the banking business to Asia.

Their loss could be our gain, that’s if we heed of the fundamental truism shown above.

Saturday, April 16, 2011

War on Economics: China Imposes Price Controls!

The war on economics has begun.

After four interest rate increase, and having failed to curtail inflation, China has started to impose price controls!

From the Financial Times, (bold highlights mine)

China has imposed strict price controls on basic consumer items and is expected to allow faster appreciation of its currency in the coming months after annual inflation in the country reached its highest level in nearly three years in March.

In a speech this week to the governing State Council, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao said Beijing would, along with other policy measures, “further improve the yuan exchange rate mechanism and increase yuan exchange rate flexibility to eliminate inflationary monetary conditions”...

The price department of China’s powerful state planning agency – the National Development and Reform Commission – met earlier this month with 17 industry associations and ordered them to delay or cancel planned price increases.

The quasi-government industry associations included those overseeing agriculture, pharmaceuticals, fisheries, home appliances, cosmetics, meat, vegetables and many other basic consumer items.

In the past week or so the NDRC has also directly ordered flour and cooking oil producers to delay price increases, according to state media reports, and has even applied price controls to large global groups operating in China, such as Unilever

Price controls, which implies limits on production (yes, who will sell at a loss?, Who will work for free???), will only aggravate shortages rather than solve the problem.

From Wikipedia.org

As Wikipedia explains

Suppliers find they can't charge what they had been. As a result, some suppliers drop out of the market. This reduces supply. Meanwhile, consumers find they can now buy the product for less, so quantity demanded increases. These two actions cause quantity demanded to exceed quantity supplied, which causes a shortage—unless rationing or other consumption controls are enforced.

This serves as a politically convenient short-term approach but nonetheless a foolish one because it defies basic economics that comes nasty repercussions (rationing, long lines, more political instability).

The Romans tried it, US President Nixon tried it and many political authorities spanning 4 centuries tried it but all of them failed. Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez has also recently implemented this but has even worsened inflation and shortages.

And these have been so predictable.

First politicians create inflation by debasing the currency.

Next, politicians blame the market for self inflicted ills, thereby, superficially react to such imbalances by imposing price controls which eventually backfires.

As the great Ludwig von Mises wrote,

those engaged in futile and hopeless attempts to fight the inevitable consequences of inflation — the rise in prices — are masquerading their endeavors as a fight against inflation. While fighting the symptoms, they pretend to fight the root causes of the evil. And because they do not comprehend the causal relation between the increase in money in circulation and credit expansion on the one hand and the rise in prices on the other, they practically make things worse.

The policy of price control is where George Santayana’s damning admonition...“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”...reverberates.

Thursday, March 24, 2011

Video: Understanding The Difference Between Private and Public Enterprises

Thursday, March 10, 2011

The Economic Basics of Protectionism

This is great stuff from Professor Mark Perry. Economics 101 of Protectionism versus Free trade.

Professor Perry writes, (bold emphasis mine)

The graphical analysis above shows what happens economically to a country that moves from: a) free trade with the rest of the world, with consumers paying the world price for a given product, to a b) protectionist trade policy and a new higher price that includes a tariff (tax) that reduces the amount of trade that takes place. Here are the key outcomes of this protectionism:

1. The domestic producers are now better off because they are protected from more efficient foreign competition, and can charge higher prices and increase output. Economically, they have converted consumer surplus (gains) to producer surplus (gains) because of the tariff, and that transfer is represented by the yellow area labeled "Producer Surplus" above. Nothing lost there on net because of the tariff, although domestic producers have used the political process to gain at the direct expense of domestic consumers, who now pay higher prices and purchase fewer units.

2. With a tariff (tax) on imports, the government is now able to generate "Tax Revenue" in an amount represented by the blue rectangle above. This is also a transfer, this time from what used to be consumer surplus (gains from trade) to the federal government. Nothing necessarily lost here either on net, assuming that the government will transfer the tax revenue back to the consumers in the form of beneficial government spending (maybe) or lower taxes elsewhere (maybe).

3. However, the two pink triangles labeled "Societal Loss" are the amount of losses to the consumers and the economy (society) from the protectionist tariffs that are NOT offset by a gain to some other group: producers or government, and represent what economists call the "deadweight loss" or "deadweight cost" of protectionism.

Bottom Line: The deadweight losses from protectionism mean that the economy is worse off on net, or that there has been a reduction in total economic welfare, the total number of jobs, wealth, prosperity, and/or national income. You could argue about the size of the deadweight loss triangles, but it would be really hard to argue that they don't exist. Protectionism has to make the country worse off, on net, and that proposition is supported by 200 years of economic theory and hundreds of empirical studies.

Two additional comments:

-You get economic lessons free on the web.

-When you get to hear people babble about the benefits of protectionism, you can be assured that they’re not dealing with economic realities. Instead, protectionism is grounded on emotionally charged politics—characterized by the rhetoric of good intentions (social signaling or arguing for social conformity purposes or for getting votes), rather than what truly works.