The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Thursday, July 19, 2012

Video: Murray Rothbard on the Origin of the US Federal Reserve

Friday, June 29, 2012

BSP's loan to the IMF: Costs are Not Benefits

The simmering debate over the proposed loan to the IMF by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) can be summarized as:

For the anti-camp, the issue is largely one of purse control or where to spend the government (or in particular the BSP’s money) seen from the moral dimensions.

For the pro-camp or the apologists for the BSP and the government, the argument has been made mostly over the opportunity cost of capital or (Wikipedia.org) or the expected rate of return forgone by bypassing of other potential investment activities, e.g. best “riskless” way to earn money, appeal to tradition, e.g. Philippines has been lending money to the IMF for decades, and with some quirk “foreign exchange assets …are not like money held by the treasury” which is meant to dissociate the argument of purse control with central bank policies.

I will be dealing with latter

This assertion “foreign exchange assets …are not like money held by the treasury” is technically true or valid in terms of FORM, but false in terms of SUBSTANCE.

Foreign exchange assets are in reality products of Central Banking monetary or foreign exchange policies of buying and selling of official international reserves (Wikipedia.org)

This means that foreign exchange assets and reserves are acquired and sold by the BSP with local currency units, or the Philippine Peso, prices of which are set by the marketplace

It is important to address the fact that the local currency the Peso has been mandated as legal tender by The New Central Bank Act or REPUBLIC ACT No. 7653 which says

Section 52. Legal Tender Power. -

All notes and coins issued by the Bangko Sentral shall be fully guaranteed by the Government of the Republic of the Philippines and shall be legal tender in the Philippines for all debts, both public and private

This means that ALL transactions made by the BSP based on the Peso are guaranteed by the Philippine government. This also further implies that foreign exchange assets held by the BSP, which were bought with the Peso, are underwritten by the local taxpayers. Therefore claims that taxpayer money as not being exposed to the proposed BSP $1 billion loan to the IMF are unfounded, if not downright silly. We don’t need to drill down on the content of the balance sheet and the definition of International Reserves for the BSP to further prove this point.

The more important point here: whether foreign exchange or treasury or private sector assets, we are dealing with money.

And money, as the great Austrian professor Ludwig von Mises pointed out, must necessarily be an economic good, the notion of a money that would not be scarce is absurd.

As a scarce good, money held by the National government or by the BSP is NOT money held by the private sector.

Therefore the government or the BSP’s “earnings” translates to lost “earnings” for the private sector.

Costs are not benefits. To paraphrase Professor Don Boudreaux, that the benefit the BSP gets from investing in the asset markets might make sacrificing some unseen private sector industries worthwhile does not mean such sacrifices are a benefit in and of itself.

The public sees what has only been made to be seen by politics. Yet the public does not see the opportunities lost from such actions. Therefore, the cost-benefit tradeoff cannot be fully established.

Besides, any idea that loans to the IMF is risk free is a myth. There is no such thing as risk free. The laws of economics cannot be made to disappear, or cannot become subservient, to mere government edicts as today’s crisis has shown. Remember the IMF depends on contributions from taxpayers of member nations. And for many reasons where taxpayers of these nations might resist to contribute further, and or where the loan exposures by the IMF does not get paid, then the IMF will be in a deep hole.

As I pointed previous out the risk to IMF’s loan to crisis nation are real. There hardly has been anything to enforce loan covenants or deals made with EU's crisis restricted nations.

Also, it is naïve to believe that just because the Philippines has had a track record of lending to the IMF, that such actions makes it automatically financially viable or moral. This heuristics (mental short cut) wishes away the nitty gritty realities of the distinctive risks-return tradeoffs, as well as the moral issues, attendant to every transaction. Here the Wall Street saw applies: Past performance does not guarantee future outcomes.

It is further misguided to believe that the government (in particular the BSP) behaves like any other private enterprises.

As a side note, I find it funny how apologists use logical verbal sleight of hand in attempting to distinguish central bank operations from treasury operations but ironically and spuriously attempts to synthesize the functionality of government and private enterprises.

Two reasons:

1. Central banks are political institutions with political goals.

As the great dean of Austrian School of economics, Murray N. Rothbard pointed out,

The Central Bank has always had two major roles: (1) to help finance the government's deficit; and (2) to cartelize the private commercial banks in the country, so as to help remove the two great market limits on their expansion of credit, on their propensity to counterfeit: a possible loss of confidence leading to bank runs; and the loss of reserves should any one bank expand its own credit. For cartels on the market, even if they are to each firm's advantage, are very difficult to sustain unless government enforces the cartel. In the area of fractional-reserve banking, the Central Bank can assist cartelization by removing or alleviating these two basic free-market limits on banks' inflationary expansion credit.

2. The guiding incentives and structure of operations for government agencies (not limited to the BSP) is totally different from profit-loss driven private enterprises.

Again Professor Rothbard,

Proponents of government enterprise may retort that the government could simply tell its bureau to act as if it were a profit-making enterprise and to establish itself in the same way as a private business. There are two flaws in this theory. First, it is impossible to play enterprise. Enterprise means risking one's own money in investment. Bureaucratic managers and politicians have no real incentive to develop entrepreneurial skill, to really adjust to consumer demands. They do not risk loss of their money in the enterprise. Secondly, aside from the question of incentives, even the most eager managers could not function as a business. Regardless of the treatment accorded the operation after it is established, the initial launching of the firm is made with government money, and therefore by coercive levy. An arbitrary element has been "built into" the very vitals of the enterprise. Further, any future expenditures may be made out of tax funds, and therefore the decisions of the managers will be subject to the same flaw. The ease of obtaining money will inherently distort the operations of the government enterprise. Moreover, suppose the government "invests" in an enterprise, E. Either the free market, left alone, would also have invested the same amount in the selfsame enterprise, or it would not. If it would have, then the economy suffers at least from the "take" going to the intermediary bureaucracy. If not, and this is almost certain, then it follows immediately that the expenditure on E is a distortion of private utility on the market — that some other expenditure would have greater monetary returns. It follows once again that a government enterprise cannot duplicate the conditions of private business.

In addition, the establishment of government enterprise creates an inherent competitive advantage over private firms, for at least part of its capital was gained by coercion rather than service. It is clear that government, with its subsidization, if it wishes can drive private business out of the field. Private investment in the same industry will be greatly restricted, since future investors will anticipate losses at the hands of the privileged governmental competitors. Moreover, since all services compete for the consumer's dollar, all private firms and all private investment will to some degree be affected and hampered. And when a government enterprise opens, it generates fears in other industries that they will be next, and that they will be either confiscated or forced to compete with government-subsidized enterprises. This fear tends to repress productive investment further and thus lower the general standard of living still more.

From here we derive the third view that distinguishes from the two mainstream camps:

Government is NOT supposed to “earn” money. Government should leave the private sector to earn from productive undertakings. Whatever “surpluses” or “earnings” should be given back to the taxpayers. How? By reducing taxes, by cutting down government spending and or by paying down public debt.

The “returns” from these actions will surely outweigh gains made from political speculations. Unfortunately this has been unseen.

As the great Frederic Bastiat once remarked

Between a good and a bad economist this constitutes the whole difference - the one takes account of the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effects which are seen, and also of those which it is necessary to foresee. Now this difference is enormous, for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favourable, the ultimate consequences are fatal, and the converse. Hence it follows that the bad economist pursues a small present good, which will be followed by a great evil to come, while the true economist pursues a great good to come, - at the risk of a small present evil.

Friday, March 23, 2012

The Mythical World of Ben Bernanke

For Ben Bernanke and their ilk, the world exists in a causation vacuum, as things are just seen as they are, as if they are simply "given". And people’s action expressed by the marketplace, are seen as fallible, which only requires the steering guidance of the technocracy (the arrogant dogmatic belief that political authorities are far knowledgeable than the public).

Monetary economist Professor George Selgin majestically blasts Ben Bernanke’s self-glorification. (bold emphasis mine)

So like any central banker, and unlike better academic economists, Bernanke consistently portrays inflation, business cycles, financial crises, and asset price "bubbles" as things that happen because...well, the point is that there is generally no "because." These things just happen; central banks, on the other hand, exist to prevent them from happening, or to "mitigate" them once they happen, or perhaps (as in the case of "bubbles") to simply tolerate them, because they can't do any better than that. That central banks' own policies might actually cause inflation, or contribute to the business cycle, or trigger crises, or blow-up asset bubbles--these are possibilities to which every economist worth his or her salt attaches some importance, if not overwhelming importance. But they are also possibilities that every true-blue central banker avoids like so many landmines. Are you old enough to remember that publicity shot of Arthur Burns holding a baseball bat and declaring that he was about to "knock inflation out of the economy"? That was Burns talking, not like a monetary economist, but like the Fed propagandist that he was. Bernanke talks the same way throughout much (though not quite all) of his lecture.

And for the central bank religion, politics has never been an issue. It’s always been about the virtuous state of public service channeled through economic policies…

In describing the historical origins of central banking, for instance, Bernanke makes no mention at all of the fiscal purpose of all of the earliest central banks--that is, of the fact that they were set up, not to combat inflation or crises or cycles but to provide financial relief to their sponsoring governments in return for monopoly privileges. He is thus able to steer clear of the thorny challenge of explaining just how it was that institutions established for function X happened to prove ideally suited for functions Y and Z, even though the latter functions never even entered the minds of the institutions' sponsors or designers!

By ignoring the true origins of early central banks, and of the Bank of England in particular, and simply asserting that the (immaculately conceived) Bank gradually figured-out its "true" purpose, especially by discovering that it could save the British economy now and then by serving as a Lender of Last Resort, Bernanke is able to overlook the important possibility that central banks' monopoly privileges--and their monopoly of paper currency especially--may have been a contributing cause of 19th-century financial instability. How currency monopoly contributed to instability is something I've explained elsewhere. More to the point, it is something that Walter Bagehot was perfectly clear about in his famous 1873 work, Lombard Street. Bernanke, in typical central-bank-apologist fashion, refers to Bagehot's work, but only to recite Bagehot's rules for last-resort lending. He thus allows all those innocent GWU students to suppose (as was surely his intent) that Bagehot considered central banking a jolly good thing. In fact, as anyone who actually reads Bagehot will see, he emphatically considered central banking--or what he called England's "one-reserve system" of banking--a very bad thing, best avoided in favor of a "natural" system, like Scotland's, in which numerous competing banks of issue are each responsible for maintaining their own cash reserves.

People hardly realize that central banks had been born out of politics and survives on taxpayer money which is politics, and eventually will die out of politics.

Any discussion of politics affecting central banking policymaking has to be purposely skirted or evaded.

Policies must be painted as having positive influences or at worst neutral effects. This leaves all flaws attributable to the marketplace.

In reality, any admission to the negative consequence of the central bank polices would extrapolate to self-incrimination for central bankers and the risk of losing their politically endowed privileges.

Besides ignoring the destabilizing effects of central banking--or of any system based on a currency monopoly--Bernanke carefully avoids any mention of the destabilizing effects of other sorts of misguided financial regulation. He thus attributes the greater frequency of banking crises in the post-Civil War U.S. than in England solely to the lack of a central bank in the former country, making one wish that some clever GWU student had interrupted him to observe that Canada and Scotland, despite also lacking central banks, each had far fewer crises than either the U.S. or England. Hearing Bernanke you would never guess that U.S. banks were generally denied the ability to branch, or that state chartered banks were prevented by a prohibitive federal tax from issuing their own notes, or that National banks found it increasingly difficult to issue their own notes owing to the high cost of government securities required (originally for fiscal reasons) as backing for their notes. Certainly you would not realize that economic historians have long recognized (see, for starters, here andhere) how these regulations played a crucial part in pre-Fed U.S. financial instability. No: you would be left to assume that U.S. crises just...happened, or rather, that they happened "because" there was no central bank around to put a stop to them.

Because he entirely overlooks the role played by legal restrictions in destabilizing the pre-1914 U.S. financial system, Bernanke is bound to overlook as well the historically important "asset currency" reform movement that anticipated the post-1907 turn toward a central-bank based monetary reform. Instead of calling for yet more government intervention in the monetary system the earlier movement proposed a number of deregulatory solutions to periodic financial crises, including the repeal of Civil-War era currency-backing requirements and the dismantlement of barriers to nationwide branch banking. Canada's experience suggested that this deregulatory program might have worked very well. Unfortunately concerted opposition to branch banking, by both established "independent" bankers and Wall Street (which gained lots of correspondent business thanks to other banks' inability to have branches there) blocked this avenue of reform. Instead of mentioning any of this, Bernanke refers only to the alternative of relying upon private clearinghouses to handle panics, which he says "just wasn't sufficient." True enough. But the Fed, first of all (as Bernanke himself goes on to admit, and as Friedman and Schwartz argue at length), turned out be be an even less adequate solution than the clearinghouses had been; more importantly, the clearinghouses themselves, far from having been the sole or best alternative to a central bank, were but a poor second-best substitute for needed deregulation.

To be fair, Bernanke does eventually get 'round to offering a theory of crises. The theory is the one according to which a rumor spreads to the effect that some bank or banks may be in trouble, which is supposedly enough to trigger a "contagion" of fear that has everyone scrambling for their dough. Bernanke refers listeners to Frank Capra's movie "It's a Wonderful Life," as though it offered some sort of ground for taking the theory seriously, though admittedly he might have done worse by referring them to Diamond and Dybvig's (1983) even more factitious journal article. Either way, the impression left is one that ought to make any thinking person wonder how any bank ever managed to last for more than a few hours in those awful pre-deposit insurance days. That quite a few banks, and especially ones that could diversify through branching, did considerably better than that is of course a problem for the theory, though one Bernanke never mentions. (Neither, for that matter, do many monetary economists, most of whom seem to judge theories, not according to how well they stand up to the facts, but according to how many papers you can spin off from them.) In particular, he never mentions the fact that Canada had no bank failures at all during the 1930s, despite having had no central bank until 1935, and no deposit insurance until many decades later. Nor does he acknowledge research by George Kaufman, among others, showing that bank run "contagions" have actually been rare even in the relatively fragile U.S. banking system. (Although it resembled a system-wide contagion, the panic of late February 1933 was actually a speculative attack on the dollar spurred on by the fear that Roosevelt was going to devalue it--which of course he eventually did.) And although Bernanke shows a chart depicting high U.S. bank failure rates in the years prior to the Fed's establishment, he cuts it off so that no one can observe how those failure rates increased after 1914. Finally, Bernanke suggests that the Fed, acting in accordance with his theory, only offers last-resort aid to solvent ("Jimmy Stewart") banks, leaving others to fail, whereas in fact the record shows that, after the sorry experience of the Great Depression (when it let poor Jimmy fend for himself), the Fed went on to employ its last resort lending powers, not to rescue solvent banks (which for the most part no longer needed any help from it), but to bail out manifestly insolvent ones. All of these "overlooked" facts suggest that there is something not quite right about the suggestion that bank failure rates are highest when there is neither a central bank nor deposit insurance. But why complicate things? The story is a cinch to teach, and the Diamond-Dybvig model is so..."elegant." Besides, who wants to spoil the plot of "It's a Wonderful Life?"

Cherry picking of reference points and censorship had been applied on historical accounts that does not favor central banking.

Of course, it is natural for central bankers to be averse to the gold standard. A gold standard would reduce or extinguish central banker’s (as well as politicians') political control over money.

Bernanke's discussion of the gold standard is perhaps the low point of a generally poor performance, consisting of little more than the usual catalog of anti-gold clichés: like most critics of the gold standard, Bernanke is evidently so convinced of its rottenness that it has never occurred to him to check whether the standard arguments against it have any merit. Thus he says, referring to an old Friedman essay, that the gold standard wastes resources. He neglects to tell his listeners (1) that for his calculations Friedman assumed 100% gold reserves, instead of the "paper thin" reserves that, according to Bernanke himself, where actually relied upon during the gold standard era; (2) that Friedman subsequently wrote an article on "The Resource Costs of Irredeemable Paper Money" in which he questioned his own, previous assumption that paper money was cheaper than gold; and (3) that the flow of resources to gold mining and processing is mainly a function of gold's relative price, and that that relative price has been higher since 1971 than it was during the classical gold standard era, thanks mainly to the heightened demand for gold as a hedge against fiat-money-based inflation. Indeed, the real price of gold is higher today than it has ever been except for a brief interval during the 1980s. So, Ben: while you chuckle about how silly it would be to embrace a monetary standard that tends to enrich foreign gold miners, perhaps you should consider how no monetary standard has done so more than the one you yourself have been managing!

Bernanke's claim that output was more volatile under the gold standard than it has been in recent decades is equally unsound. True: some old statistics support it; but those have been overturned by Christina Romer's more recent estimates, which show the standard deviation of real GNP since World War II to be only slightly greater than that for the pre-Fed period. (For a detailed and up-to-date comparison of pre-1914 and post-1945 U.S. economic volatility see my, Bill Lastrapes, and Larry White's forthcoming Journal of Macroeconomics paper, "Has the Fed Been a Failure?").

Nor is Bernanke on solid ground in suggesting that the gold standard was harmful because it resulted in gradual deflation for most of the gold-standard era. True, farmers wanted higher prices for their crops, if not general inflation to erode the value of their debts--when haven't they? But generally the deflation of the 19th century did no harm at all, because it was roughly consistent with productivity gains of the era, and so reflected falling unit production costs. As a self-proclaimed fan of Friedman and Schwartz, Bernanke ought to be aware of their own conclusion that the secular deflation he complains about was perfectly benign. Or else he should read Saul's The Myth of the Great the Great Depression, or Atkeson and Kehoe's more recent AER article, or my Less Than Zero. In short, he should inform himself of the fundamental difference between supply-drive and demand-driven deflation, instead of lumping them together, and lecture students accordingly.

Although he admits later in his lecture (in his sole acknowledgement of central bankers' capacity to do harm) that the Federal Reserve was itself to blame for the excessive monetary tightening of the early 1930s, in his discussion of the gold standard Bernanke repeats the canard that the Fed's hands were tied by that standard. The facts show otherwise: Federal Reserve rules required 40% gold backing of outstanding Federal Reserve notes. But the Fed wasn’t constrained by this requirement, which it had statutory authority to suspend at any time for an indefinite period. More importantly, during the first stages of the Great (monetary) Contraction, the Fed had plenty of gold and was actually accumulating more of it. By August 1931, it's gold holdings had risen to $3.5 billion (from $3.1 billion in 1929), which was 81% of its then-outstanding notes, or more than twice its required holdings. And although Fed gold holdings then started to decline, by March 1933, which is to say the very nadir of the monetary contraction, the Fed still held over than $1 billion in excess gold reserves. In short, at no point of the Great Contraction was the Fed prevented from further expanding the monetary base by a lack of required gold cover.

Finally, Bernanke repeats the tired old claim that the gold standard is no good because gold supply shocks will cause the value of money to fluctuate. It is of course easy to show that gold will be inferior on this score to an ideally managed fiat standard. But so what? The question is, how do the price movements under gold compare to those under actual fiat standards? Has Bernanke compared the post-Sutter's Mill inflation to that of, say, the Fed's first five years, or the 1970s? Has he compared the average annual inflation rate during the so-called "price revolution" of the 16th century--a result of massive gold imports from the New-World--to the average U.S. rate during his own tenure as Fed chairman? If he bothered to do so, I dare say he'd clam up about those terrible gold supply shocks.

So when it comes to the gold standard, it is not only the omission of facts and of glaring blind spots, but importantly, it is about deliberate twisting of the facts! At least they practice what they preach--they manipulate the markets too.

Now this is what we call propaganda.

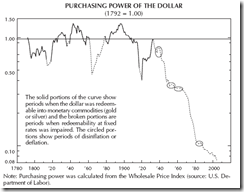

It is best to point out how Bernanke’s central banking has destroyed the purchasing power of the US dollar as shown in the chart above.

Yet here is another example of the mainstream falling for Bernanke’s canard.

Writes analyst David Fuller,

Preservation of purchasing power is the main reason why anyone would favour a gold standard. However, if we assume, hypothetically, that the US and other leading countries moved back on to a gold standard, I do not think many of us would like the deflationary consequences that followed. Also, a gold standard would almost certainly involve the confiscation of private holdings of bullion, as has occurred previously. Most of us would not like to lose our freedom to hold bullion.

I have long argued that we would never see the reintroduction of a gold standard because no leading government is likely to surrender control over its own money supply. For current reasons, just ask the Greeks or citizens of other peripheral Eurozone countries, struggling to cope with no more than a euro standard.

There would also be national security issues as it would not be difficult for rogue states to manipulate the price of bullion as an act of economic war.

First of all, the paper money system is not, and will not be immune to the deflationary impact caused by an inflationary boom. That’s why business cycles exist. Under government’s repeated doping of the marketplace we would either see episodes of monetary deflation (bubble bust) or a destruction of the currency system (hyperinflation) at the extremes.

As Professor Ludwig von Mises wrote

The wavelike movement affecting the economic system, the recurrence of periods of boom which are followed by periods of depression, is the unavoidable outcome of the attempts, repeated again and again, to lower the gross market rate of interest by means of credit expansion. There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.

Next, as previously pointed out the intellectuals and political authorities resort to semantic tricks to mislead the public.

Deflation caused by productivity gains (pointed out by Professor Selgin) isn’t bad but rather has positive impacts—as evidenced by the advances of technology.

Rather it is the money pumping and the leverage (gearing), or the erosion of real wealth, caused by prior inflationism from the central bank sponsored banking system. These political actions spawns outsized fluctuations and the adverse ramifications of monetary deflation.

And it is the banking system will be more impacted than that the real economy which is the reason for these massive bailouts and expansion of balance sheets of central banks. It's about political interest than of public interests.

In addition, it is wildly inaccurate to claim to say gold standard would “involve the confiscation of private holdings of bullion”. FDR’s EO 6102 in 1933 came at the end of the gold bullion standard which is different from the classical gold standard. In the classic gold standard, gold (coins) are used as money or the medium of exchange, so confiscation of gold would mean no money in circulation. How logical would this be?

Finally while the assertions that “no leading government is likely to surrender control” seems plausible, this seems predicated on money as a product of governments—which is false. Effects should not be read as causes.

As the great F. A. Hayek wrote (Denationalization of Money p.37-38)

It the superstition that it is necessary for government (usually called the 'state' to make it sound better) to declare what is to be money, as if it had created the money which could not exist without it, probably originated in the naive belief that such a tool as money must have been 'invented' and given to us by some original inventor. This belief has been wholly displaced by our understanding of the spontaneous generation of such undesigned institutions by a process of social evolution of which money has since become the prime paradigm (law, language and morals being the other main instances).

If governments has magically transformed money into inviolable instruments then hyperinflation would have never existed.

At the end of the day, the world in which central bankers and their minions portray seems no less than vicious propaganda.

Sunday, March 18, 2012

Global Stock Markets: Will the Recent Rise in Interest Rates Pop the Bubble?

The natural tendency of government, once in charge of money, is to inflate and to destroy the value of the currency. To understand this truth, we must examine the nature of government and of the creation of money. Throughout history, governments have been chronically short of revenue. The reason should be clear: unlike you and me, governments do not produce useful goods and services that they can sell on the market; governments, rather than producing and selling services, live parasitically off the market and off society. Unlike every other person and institution in society, government obtains its revenue from coercion, from taxation. In older and saner times, indeed, the king was able to obtain sufficient revenue from the products of his own private lands and forests, as well as through highway tolls. For the State to achieve regularized, peacetime taxation was a struggle of centuries. And even after taxation was established, the kings realized that they could not easily impose new taxes or higher rates on old levies; if they did so, revolution was very apt to break out.-Murray N. Rothbard

The rampaging bullmarket here and abroad has raised concerns that recent increases in nominal interest rates could put a kibosh to the current run.

As I pointed out before, the actions in the interest rates markets will be shaped by different circumstances[1] which means it is not helpful to apply one size fits all analysis to potentially variable scenarios that may arise.

Interest rates may reflect on changes in consumer price inflation, they may also reflect on the perception of credit quality and they may reflect also on the state of demand for credit relative to the scarcity or availability of savings or capital[2].

Since the current interest rate environment has been mostly manipulated by political actions, where the political goal has supposedly been to whet aggregate demand by bringing interest rates towards zero, then we are dealing with a policy based negative real rates economic environment.

So the crucial issue is, has the recent selloff in treasury bonds neutralized the negative real rates regime? The answer is no.

First of all, current environment has not been reflecting concerns over deterioration of credit quality as measured through credit spreads[3], which seem to have eased.

Also, milestone highs reached by global stock markets, led by the US, have encouraged complacency through a reduction of volatility[4].

Second, the yield curve of US treasuries despite having flattened (perhaps due to policy manipulations) still manifests opportunities for maturity transformation trade or lending activities.

Thus, we are seeing signs of recovery in business and commercial lending in the US.

Some of the banking system’s excess reserves held at the US Federal Reserve seem to be finding its way into the economy.

Lastly, many are still in denial that inflation poses a risk, despite rising Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS).

TIPs are government issued treasury securities indexed to the consumer price index (CPI) with maturity ranging from 5 to 30 years which are usually considered as inflation hedges. (That’s if you believe on the accuracy of the CPI index. I don’t)

TIPs seem to have converged with the S&P 500.

Financial markets could be pricing in a risk ON environment and real economic activities, calibrated by the current negative real rates regime, combined with signs of escalating consumer price inflation.

The reality is that mainstream and the political establishment will continue to deny that inflation exists, when the US Federal Reserve has already been rampantly inflating.

Monetary inflation is inflation. However the public is being misled by semantics of inflation by pointing to consumer price inflation.

As Professor Ludwig von Mises wrote[5],

To avoid being blamed for the nefarious consequences of inflation, the government and its henchmen resort to a semantic trick. They try to change the meaning of the terms. They call "inflation" the inevitable consequence of inflation, namely, the rise in prices. They are anxious to relegate into oblivion the fact that this rise is produced by an increase in the amount of money and money substitutes. They never mention this increase

They put the responsibility for the rising cost of living on business, This is a classical case of the thief crying "catch the thief." The government, which produced the inflation by multiplying the supply of money, incriminates the manufacturers and merchants and glories in the role of being a champion of low prices. While the Office of Stabilization and Price Control is busy annoying sellers as well as consumers by a flood of decrees and regulations, the only effect of which is scarcity, the Treasury goes on with inflation.

That’s because any acknowledgement of inflation would put to a stop or would prompt for a reversal of the Fed’s accommodative policies. And considering that the banking system has been laden with bad loans, and that welfare based governments have unsustainable Ponzi financing liabilities, then tightening money conditions, expressed through higher interest rates, means the collapse of the system.

Underneath the seeming placid signs of today’s marketplace have been central banking steroids at work as the balance sheets of major economies have soared to uncharted territories[6].

The US Fed and the ECB, as well as other central banks, including the local BSP, will work to sustain negative interest rates environment, no matter any publicized rhetoric to the contrary. There may be some internal objections by a few policy makers, but all these have signified as noises more than actual actions. The politics of the establishment has drowned out any resistance as shown by central banks balance sheets.

One must remember that the US Federal Reserve was created out of politics[7], exists or survives through political money and will die through politics. And so with the rest of central banks.

Thus there is NO way that central bankers will not be influenced[8] by political leaders, their networks and by the regulated. Political power always has corrupting influences.

A good example can be gleaned from Independent Institute research fellow Vern McKinley’s comments[9] on U.S. Treasury secretary Mr. Timothy Geithner’s recent Op Ed[10]

He recounts how the CEO of Bear, with his firm on the brink of bankruptcy, came to him looking for a shoulder to cry on. From his then leadership perch as president of the New York Fed, the bank ultimately extended nearly $30 billion for a bailout, the first in a series of such interventions.

Central bankers are human beings. Only people deprived of reason fail to see the realities of government’s role.

And since the FED has unleashed what used to be a nuclear option, other central banks have learned to assimilate the FED’s policy. This essentially transforms what used to be a contingency measure into conventional policymaking.

As been said before, inflationism has produced an unprecedented state of dependency

And that such state of dependency can be seen through the dramatically expanding role of non-market forces or the government.

As Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart observed in her Bloomberg column[11],

In the U.S. Treasury market, the increasing role of official players (or conversely the shrinking role of “outside market players”) is made plain in Figure 3, which shows the evolution from 1945 through 2010 of the share of “outside” marketable U.S. Treasury securities plus those of so-called government-sponsored enterprises, such as the mortgage companies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The combination of the Federal Reserve’s two rounds of quantitative easing and, more importantly, record purchases of U.S. Treasuries (and quasi-Treasuries, the government-sponsored enterprises, or GSEs) by foreign central banks (notably China) has left the share of outside marketable Treasury securities at almost 50 percent, and when GSEs are included, below 65 percent.

These are the lowest shares since the expansive monetary policy stance of the U.S. regularly associated with the breakdown of Bretton Woods in the early 1970s. That, too, was a period of rising oil, gold and commodity prices, negative real interest rates, currency turmoil and, eventually, higher inflation.

This is not an issue involving economics alone. This is an issue involving the survival of the current state of the political institutions.

Bottom line: Rising interest rates will pop the bubble one day. But we have not reached this point yet.

Again, the raft of credit easing measures announced last month will likely push equity market higher perhaps until the first semester or somewhere at near the end of these programs. Of course there will be sporadic shallow short term corrections amidst the current surge.

However, the next downside volatility will only serve as pretext for more injections until the market will upend such policies most likely through intensified price inflation.

[1] See Global Equity Market’s Inflationary Boom: Divergent Returns On Convergent Actions, February 13, 2011

[2] See I Told You Moment: Philippine Phisix At Historic Highs! January 15, 2012

[3] Danske Bank, The US bond market finally surrendered, Weekly Focus March 16, 2012

[4] See Graphics: The Risk On Environment March 14, 2012

[5] Mises, Ludwig von 19 Inflation Economic Freedom and Interventionism Mises.org

[6] Zero Hedge, Is This The Chart Of A Broken Inflation Transmission Mechanism? March 13, 2012

[7] See The US Federal Reserve: The Creature From Jekyll Island, July 3, 2009

[8] See Paul Volcker Warns Ben Bernanke: A Little Extra Inflation Would Backfire, March 16, 2012

[9] McKinley Vern Timothy Geithner's Bailout Legacy Not One To Be Proud Of, Investor’s Business Daily March 15, 2012

[10] Geithner Timothy Op-Ed: ‘Financial Crisis Amnesia’ Treasury.gov March 1, 2012

[11] Reinhart Carmen Financial Repression Has Come Back to Stay, Bloomberg.com March 12, 2012

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

Video: A History of Central Banking

Here is a short video on the history of Central Banking from Cato’s Dan Mitchell...

Here is the list of US and world financial crisis from Misis.org wiki (click on the link to redirect you to the page)

Here is a graph of the number of banking crisis worldwide post the Nixon Shock or the End of the Bretton Woods standard (from the World Bank)

The reason I had to include these is to illustrate how central banks have fundamentally failed to contain panics-the rationalized role for their existence.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Quote of the Day on Wall Street: After Nearly A Century, Hardly Any Change

``The bankers, however, faced a big public relations problem. What they wanted was the federal government creating and enforcing a banking cartel by means of a Central Bank. Yet they faced a political climate that was hostile to monopoly and centralization, and favored free competition. They also faced a public opinion hostile to Wall Street and to what they perceptively but inchoately saw as the "money power."" (bold highlights mine)

So the problem of nearly 100 years ago is basically the same as today! The difference is that the Federal Reserve- banking cartel has been realized, but is still under fire.