``Gold was not selected arbitrarily by governments to be the monetary standard. Gold had developed for many centuries on the free market as the best money; as the commodity providing the most stable and desirable monetary medium." - Murray N. Rothbard, What Has Government Done to Our Money?

In this issue:

Is Gold In A Bubble?

-Fed’s Quantitative Easing Update

-Misrepresenting Gold’s History

-The Misunderstood Role Of Central Bankers

-Appraising Gold And The Origin of Money

-Crack Up Boom Versus Bubble Psychology

Fed’s Quantitative Easing Update

The US Federal Reserve has vastly accelerated its purchases of US treasuries to the tune of about $7 billion, based on the data from the Federal Bank of Cleveland. This has been in breach of its self-imposed limits.

Likewise, the increased treasury purchases appears to be in line with the commencement of the next wave of mortgage resets that seems likely to signify as the next round of strains to the US banking system. As previously noted, ``With the risks of the next wave of resets from the Alt-A, Prime Mortgages, Commercial Real Estate Mortgages, aside from the Jumbo and HELOC looming larger, they are likely to exert more pressure on the banking system” [see past discussion in 5 Reasons Why The Recent Market Slump Is Not What Mainstream Expects].

Figure 1:

Sifma, Zero Hedge: US Mortgage and US Treasury Market

Since the crisis erupted, the US government, through its GSE agencies, has virtually been THE mortgage market (see left window: blue bars FED agency mortgages, gray bars private labels).

We see the same trend for US treasuries, the US government via the Federal Reserve is on its way to become the buyer of last resort- since the activation of the QE program last March, Fed purchases (black line, right window) of US treasuries accounts for almost half of the market (Zero Hedge) displacing foreign official holdings (blue line).

The above developments dispel on the flawed notions that the US government will refuse to assume the literal role as the buyer of the last resort, especially under extreme circumstances. As a political institution, once a political expediency arises-such as a renewed threat to the survivability of its banking system that could risk undermining the US dollar standard system-the US Federal Reserve will act according to its perceived priorities. And the actions in the above markets have been telling.

Misrepresenting Gold’s History

The recent spike in gold prices has evoked shrill cries of a “bubble”.

Does rising prices automatically constitute as a mania? What distinguishes a mania from structural changes?

For us, the fundamental issue is to understand the role of gold in the marketplace or in the economy than simply presuppose or generalize a bubble.

Basically, the gold debate can be delineated into two extreme camps: the gold bugs (ideological believers that money should be comprise or be backed by gold or commodity) and its antipode (ideological believers influenced by JMKeynes where gold or commodity as money is deemed as relic or a “barbaric metal”).

Of course the issue can’t be seen as simply black or white because the mainstream fundamentally operates on gray areas, out of the lack of understanding. But have mostly been tilted towards the “Barbaric” metal persuasion.

Here are some examples, (bold emphasis mine)

The Bloomberg quotes the highly distinguished trader Dennis Gartman, ``The gold bull run is not predicated upon inflation but is instead predicated upon the notion that gold is becoming a reservable asset.”

Or from Socgen’s Dylan Grice, ``How can something with no cashflow or earnings power be valued? The simple answer is that it can't be. Intrinsically it is pretty much worthless.”

Ironically Mr. Grice predicts that the price of gold to reach $6,300 primarily because of bubble psychology, the discount value of Gold relative to US dollars issued and “insolvent governments”.

On the other hand, Mr. Gartman does not qualify on the definition of, as well as, elaborate on WHY and HOW gold is “becoming a reservable asset”.

For the Barbaric metal camp, Gold is presented mostly as an unworthy investment (see figure 2)

Figure 2: Socgen: Real Prices of Gold

According to Mr. Grice, ``But the same chart also shows how unreliable gold has been as a store of wealth. A 15th century gold bug who'd stored all of his wealth in bullion, bequeathed it to his children and required them to do the same would be more than a little miffed when gazing down from his celestial place of rest to see the real wealth of his lineage decline by nearly 90% over the next 500 years (though he might take comfort from the knowledge that his financial advisor would be burning in hell). More recently, had you bought at the peak of the last bull market in January 1980 for $850, you'd have suffered a nominal decline of 70% by the time it bottomed in 1999. On an annualised basis you'd have lost 6% pa nominal and 9% real.” (bold highlight mine)

Mr. Grice’s premise seems plausible but blatantly misleads. Why?

Simply because Mr. Grice forgets to remind us that gold (including silver) was NOT held for investment, but was instead USED as money during the aforementioned eras.

And as money, gold and or silver was subjected to liquidity flows depending on the society’s perception of uncertainty, which ultimately determines the level of demand for money relative to the available supply of money. To quote Austrian economist Hans-Hermann Hoppe, ``The holding of money is a result of the systemic uncertainty of human action.”

For instance, in the mid 16th century the fall of the real price of gold (exchange value relative to other commodities) was mainly due war “conquest” financing.

According to Professor Niall Ferguson in his latest book The Ascent Of Money, ``during the so-called “price revolution”, which affected all of Europe from the 1540s until the 1640s, the cost of food-which had shown no sustained upward trend for three hundred years-rose markedly.” [italics mine]

Professor Ferguson’s account appears very consistent with the real price trend of gold on the chart, especially on the 300 years prior to the eon of war financing.

Moreover, following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire by a Spanish colonel Francisco Pizzaro, huge precious metals (money) streamed into Spain, many of which came from the Potosi (otherwise known as Domingo de Santo Tomas-mouth of hell) mines in Bolivia.

Again from Niall Ferguson’s Ascent of Money, ``between 1556 and 1783, the rich hill yielded 45,000 tons of pure silver to be transformed into bars and coins in the Casa de Moneda, and shipped to Seville…Pizarro’s conquest, it seemed, had made the Spanish crown rich beyond the dreams of avarice.” Thus, the relative surplus of gold and silver against other commodities explains anew the depressed real prices of gold and is consistent with the price action of gold chart above.

Yet going into the industrial revolution in 1800s-1913, one would observe that the real price of gold has mostly stabilized.

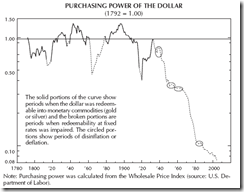

Notes Professor Michael Rozeff, ``Before there is a central bank and when metals are being used in the money and banking system, there is greater price stability. There is no contest. Pre-1913, the price level falls gently each year on the average by less than ½ of one percent. After 1913, the price level rises each year by 6.8 times as much as it used to decline before 1913 (in absolute value.)” [italics his]

Following the introduction of the US Federal Reserve in 1913, real prices of gold have gyrated mostly higher over time. And the upside volatility has been accentuated after the Nixon Shock or when former President Nixon closed the gold window or ended the Bretton Woods system on the 15th of August 1971.

In other words, the chart above from 1265-1971 or in 7 centuries gold chiefly performed the role of money. Today, this hasn’t been the case...yet.

To conclude, to use gold real prices as a metric to justify on gold’s poor investment returns is highly inconsistent, flawed and a misrepresentation. Gold’s role today isn’t like in the past where gold functioned as a medium of exchange, which should be nuanced from the current role as non-money commodity.

To add, since gold isn’t used in transactions by the general public today, then fundamentally gold isn’t money. Only to the eyes of central bankers could gold be deemed as a form of money. Thereby comparing gold as money and gold as non-money is like comparing apples to oranges.

The Misunderstood Role Of Central Bankers

Some have cited the activities of central banks as possible indication for inflection points on gold prices. For instance, the sale of UK Chancellor Gordon Brown of 400 tonnes of gold reserves in 1999 coincided with the end of the bear market. In other words, central bankers are thought to resemble retail investors, whom traditionally play the role of the greater fool during market extremes.

Yet like all human beings, while central bankers are subject to the corporeal frailties and could be influenced somewhat by the developments of the marketplace, what seem glaringly overlooked by mainstream’s oversimplification are the governing incentives from which the political bureaucracy operates on.

As Professor Ludwig von Mises rightly notes of the crux of the distinction, ``For it is a fact that as a rule the authorities are inclined to deviate from the profit system. They do not want to operate their enterprises from the viewpoint of the attainment of the greatest possible profit. They consider the accomplishment of other tasks more important. They are ready to renounce profit or at least a part of profit or even to take a loss for the achievement of other ends.” (bold emphasis mine)

So unlike typical investors driven by profits, political leaders and the bureaucracy, being political actors, fundamentally operates on political goals. In short, central banks transactions in the marketplace may represent price insensitivity, and importantly, are most likely subject to political ends that may be extraneous to market forces.

Manias are essentially founded by a massive credit boom and underpinned by government policies to create boom conditions, from which induces investor irrationality responses based on expectations of perpetually easy profits. Therefore, a gold mania cannot mechanically be attributed to central bank activities because this would highly depend on the underlying political goals in support of their activities.

Furthermore, a mania depends on pyramiding leverage or accelerating credit boom. At the present moment, central bank buying of gold has been funded from their stash of US foreign exchange surpluses.

The tiny resort island of Mauritius recently followed India to acquire 2 metric tons from the IMF (Bloomberg).

Figure 3:

Virtual Metals: Gold Demand Trends, Central Banks As Net Buyers

In addition, central banks accounted for as net buyers for the second successive quarter this year, where according to mineweb.com, ``the official sector was a net purchaser of gold in the third quarter, although the figures are low, at five tonnes in Q2 and 15 tonnes in Q3. The underlying trend is "expected to remain intact" as central banks, like private investors, continue to look for diversifiers, especially with respect to the dollar. Central banks outside the CBGA agreement that the WGC identified as gold purchasers included Mexico and the Philippines.” (see Figure 3-right window)

It is noteworthy that gold prices continue to rise, in spite of the massive net gold sales by the official sector even when gold’s bullmarket has been on the fringe.

Again from mineweb.com, ``at the end of 1998, world central bank holdings of gold amounted to 33,500 tonnes and that by the end of 2008 this was down to 29,700 tonnes so that the rate of disposal over the decade was the fastest in history - and still the price doubled.”

The important point is that the complexion of gold’s pricing dynamics has been significantly transforming from traditional “jewelry” based to “investment” based (left window). And this has been responsible for today’s buoyant gold prices, even in the face of central bank selling.

There is no better way to parse on central banking mindset than from their statements or “rationalization”. Mineweb’s Rhona O’Connell covers M. Paul Mercier, the European Central Bank's Principal Advisor in Market Operations, who in a recent speech gave four reasons why central bankers value gold.

From Ms. O’Connell (all bold and italics emphasis mine), ``The four primary reasons for a central bank to hold gold were listed as follows:

-Economic security. The physical and chemical characteristics of gold with its high density and resistance to oxidation, for example (unlike silver, the oxidation of which is the cause of tarnishing) combine with the fact that it is the only asset that is no-one else's liability to make it a vital element of foreign exchange reserves. Holding another party's securities always carries the possibility that the behaviour of the counter-party can affect the value of those securities.

-Unexpected needs. There is always a possibility, albeit very low, of highly damaging developments such as war or high inflation that can have a severe impact on sovereign debt, or result in a country's isolation. As the ultimate global means of payment gold is an important insurance policy. It can also be used as international collateral (for example the loan to the Banca d'Italia from the Bundesbank in the early 1970s).

-Confidence. Although gold no longer backs currencies in circulation, M. Mercier argued that it helps to underpin international confidence in any one currency, especially since, without gold's formal backing, currency values are based on faith in one another. He reminded us of the IMF's recent reiteration of the IMF's statement about hoe gold gives a "fundamental strength" to its balance sheet.

-Risk diversification. This, he asserts, is probably even more highly valued by central banks than it is by other investors. There is a considerable body of study that quantifies the ways in which gold brings robustness to a portfolio, most notably, for a central banker, the reduction in volatility.”

Ironically after selling 3,800 tonnes over the period where central banking dogma thought that they have successfully lorded over inflation [see Rediscovering Gold’s Monetary Appeal], counterparty risks, insurance, confidence and risk diversification suddenly becomes an issue for central bankers in reconsidering gold sales.

What has impelled them to raise such concerns?

Obviously signs like this… (all bold emphasis mine)

The Financial Times on India’s IMF’s gold’s purchase, ``Pranab Mukherjee, India’s finance minister, said the acquisition reflected the power of an economy that laid claim to the fifth-largest global foreign reserves: “We have money to buy gold. We have enough foreign exchange reserves.” He contrasted India’s strength with weakness elsewhere: “Europe collapsed and North America collapsed.”

Unsettling concerns over new bubble cycles emanating from the low interest rates regime implemented by the US Federal Reserve as articulated by the Chinese and Japanese leadership, from Bloomberg, ``“The continuous depreciation in the dollar, and the U.S. government’s indication that, in order to resume growth and maintain public confidence, it basically won’t raise interest rates for the coming 12 to 18 months, has led to massive dollar arbitrage speculation,” Liu, chairman of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, said in Beijing yesterday.

``While lower interest rates will help Americans pare debt, “there are also risks involved in continued low rates,” Shirakawa said today at a Paris Europlace Financial Forum in Tokyo. Having borrowing costs near zero may strain government finances if it spurs speculation that the dollar will continue to slide, he said, while warning that easy policy by officials globally may have repercussions in the long term.

``“Monetary easing in advanced economies has stimulated capital inflows to emerging economies,” Shirakawa said. If emerging nations continue to recover at a faster pace than advanced ones, they “might overheat and experience financial turmoil, triggering a recession,” he said.

Hong Kong’s monetary authority likewise includes the FED’s Quantitative Easing program aside from the prevailing low interest regime over concerns on formative bubbles, this from the Wall Street Journal, ``“The question one really has to ask is to what extent quantitative easing is necessary. Is the dosage right, because $2 trillion is a lot of money in the banking system, it’s high power money,” said Norman Chan, monetary authority chief executive. He and Ms. Yellen were at a forum sponsored by the Institute of Regulation & Risk. Ms. Yellen gave a speech that touched on how policymakers should address future asset bubbles.

“In Asian economies, Hong Kong included, we have seen a very massive inflow of funds that is explainable by the very low global interest rates and coupled with this huge amount of quantitative easing,” Mr. Chan said. “This question of potential risk of asset bubbles forming if this is to continue for a long period of time is a big challenge for us,” he said to Ms. Yellen.”

Basically, it’s been a predicament for Asian central banks to raise interest rates because higher rates will widen the currency yield spreads in their favor and exacerbate inward money flows. This, in essence, will blow the region’s asset bubbles faster. Yet by suppressing interest rate asset bubbles could be internally generated.

To quote CLSA’s high profile strategists Christopher Woods (highlight mine), ``The irony is that the more anaemic the Western recovery proves to be, the longer it will take for Western interest rates to normalize and the bigger the resulting asset bubble in Asia. Emerging Asia, not the U.S. consumer, will be the prime beneficiary of the Fed's easy money policy.

And the prospect of fostering asset bubbles has prompted for Asian central banks to consider imposing capital controls.

So Gartman’s argument where “gold is becoming a reservable asset” increasingly seems as a protective or insurance cover against the possible impacts from globalized systematic inflation (instead of no inflation), such as blossoming asset bubbles, emerging malinvestments, rampant speculation, financial and economic imbalances, arbitrages and carry trades, ballooning systemic leverage and surging inflation, which could all end up in tears. All these signify as inexorable monetary disorder.

In other words, many central banks have been insuring themselves, from inflation and counterparty risks by taking on gold as reservable asset. In short, gold’s appears to be gradually regaining its role as money.

Yet it would also be a grievous mistake to read bubbles as routinely blowing and popping without taking into account the magnitude where bubble cycles are becoming larger in scope and more damaging in scale upon impact when the mean reversion occurs.

Figure 4: Socgen, wikipedia: Central Bank Gold Shocks, Zimbabwe Dollar

A more fatal mistake would be to misjudge the impact from a lethal policy mix of flagrant money printing programs and low interest rate regime that could transmogrify a bubble cycle into hyperinflation.

So while global central banks could be buying gold today as shield against bubble cycles, they and everyone else would be stampeding into gold if and when the risks of a currency crisis becomes imminent.

Hence basing a projection on past performance (left window figure 4), where central banks bought during the 70s, which eventually turned into 2 gold shocks of sharply higher gold prices, assumes that present monetary disorder would be resolved in the traditional sense. We aren’t that confident. And Zimbabwe’s real life hyperinflation (right window) which ended last year should serve as reminder.

Appraising Gold And The Origin of Money

Many have made the case of valuing gold by discounting currency in circulation with that of available gold reserves.

As in the case of Socgen Dylan Grice, “So one way to value gold, therefore, is to ask at what gold price the value of outstanding central bank paper would be completely backed by gold. The US owns nearly 263m troy ounces of gold (the world's biggest holder) while the Fed's monetary base is $1.7 trillion. So the price of gold at which the US dollars would be fully gold-backed is currently around $6,300.”

Or based on Professor Michael Rozeff’s Zero Discount Value where ``value for gold such that every outstanding dollar liability in the central bank’s monetary base (currency plus bank reserves) is backed by an equivalent dollar’s worth of gold. It is what the dollar price of gold would be if the central bank’s liabilities were 100 percent backed or covered by gold.”

From our point of view, while these hypotheses could serve as meaningful concepts to measure gold, they are predicated on the assumption where variables (as monetary base) remains stable, secondly the world currency system persists on operating under the present US dollar standard, and lastly assumes that gold’s valuation in the light of current and constant conditions, hence won’t likely serve as accurate barometers, in my view.

Since we believe the world operates in a highly action-reaction dynamic, the complexity of the distribution isn’t likely to lead into a modeled outcome that can be easily captured by math estimates.

Instead we believe that policy actions are likely to be more of an accurate gauge to implied directions of the marketplace.

And it would also be true, to affirm with the behavioral camp, that human emotions will be an elaborate part of the price setting of gold, and thus is likely to cause price exaggerations beyond any models especially in bubble cycles.

In addition, while it seems conceivable to argue that gold’s rise could be a function of a bubble psychology, as per Socgen Dylan Grice, ``If my "valuation" of gold strikes you as a desperate attempt to value something which can't be valued, it's no different from metrics such as the "market cap to clicks" or "ARPU" ratios which were used in the late 1990s during the technology bubble when demand for bullish "valuation analysis" mushroomed”, this observation is far from accurate.

Yet Mr. Grice borrows some monetary aspects to rationalize an argument for a bubble cycle, ``Like today, central banks weren't buying gold in the late 1960s to prop it up, they were abandoning attempts to prop up the dollar.”

Using behavioral aspects he adds, ``Today, central banks are monetising government deficits to accommodate the recessionary effect of the credit crisis. Then the convincing narrative was that with the Middle East controlling our energy from abroad and aggressive trade unions rampant at home, policymakers were no longer in control. Today, the perception of central bank infallibility has been permanently ruptured by their collective failure to see the 2008 crash coming. Nagging concern at their over-willingness to inflate, at the blurring of monetary and fiscal policy and over long-term government solvency gives traction to a similar narrative today.”

In short, Mr. Grice utilizes the behavioral finance perspective to argue for a gold bubble and simultaneously disparage gold’s role in society.

The idea that gold is intrinsically worthless is to argue against 4,000 years of history whereby gold or silver has accounted for as money. To quote Murray Rothbard in What Has Government Done to Our Money?, ``Money is not an abstract unit of account, divorceable from a concrete good; it is not a useless token only good for exchanging; it is not a claim on society; it is not a guarantee of a fixed price level. It is simply a commodity.”

Yet gold, as commodity money, didn’t just pop out of nowhere, nor had they been they imposed by Kings or political leaders to be accepted by their constituents as money. On the contrary, historical evidences reveal that money evolved from the market’s selection process.

Some earlier forms of money that were used in select societies, such as cowrie shells in Maldives, peppers and squirrels skins in parts of Europe (The Ascent of Money), fish on the Atlantic sea coast of colonial America, beaver in the old Northwest, and tobacco, in Southern colonies (Rothbard-Mystery of Banking) salt, sugar, iron hoes, feathers, leaves and seeds, land to even huge stones weighing up to 500 lbs in the Pacific Islands of the Yap, failed to generate wider acceptance.

Instead, commodity metals, particularly of the precious metals family –gold, silver and copper- had been largely adopted due to its marketability.

According to Professor Ludwig von Mises in The Theory of Money and Credit, ``There would be an inevitable tendency for the less marketable of the series of goods used as media of exchange to be one by one rejected until at last only a single commodity remained. Which was universally employed as a medium of exchange; in a word money.”

Aside from marketability, commodity money has acquired its role due to added special traits as being highly divisible, portable, high value per unit weight and highly durable (Rothbard-Mystery of Banking).

Yet money in a conventional sense, to quote Professor Niall Ferguson in The Ascent Of Money, is a medium of exchange, which has the advantage of eliminating inefficiencies of barter; a unit of account which facilitates valuation and calculation and a store of value, which allows economic transactions to be conducted over long periods as well as geographical distances.

In other words, it would seem incoherent, if not self contradictory or plain arrogance, for anyone to claim that an object is intrinsically useless yet is considered as the most marketable combined with special traits for it to assume the role of money for thousands of years. It’s like arguing that Manny Pacquiao is a loser in spite of snaring a world record breaking title win!

Crack Up Boom Versus Bubble Psychology

Yet forecasting gold prices at $6,300 driven by plain narrative based bubble psychology is like proposing to buy or exchange something you own for something that is essentially a chimera. Or simply, would you buy rubbish simply because everybody else is doing so? How logically consistent can this be? To recall Warren Buffett’s priceless words of wisdom, ``the dumbest reason in the world to buy a stock [or any investment –mine] is because it's going up.”

Furthermore, the argument for a ‘displacement’ that would trigger a bubble cycle predicated on the rationale of “insolvent governments” ignores the psychology that drives money-FAITH.

In essence, bubble psychology deals with investor irrationality, cognitive biases and the animal spirits, which eventually revert to the mean. It underestimates and overlooks on the impact of the bubble cycles on monetary health conditions and sees a limited effect only to investment assets.

On the other hand, the truism is that money is driven by trust or faith accrued over the long years of established virtues or properties acquired which allowed money to assume its role. Confusing one for the other would be misleading.

Figure 5: Casey Research: Weimar Hyperinflation: How Faith Evaporates

As to how faith in money can vanish (see figure 5-the Weimar Germany experience) beyond the realm of behavioral finance, again this quote from Prof. von Mises, ``But then finally the masses wake up. They become suddenly aware of the fact that inflation is a deliberate policy and will go on endlessly. A breakdown occurs. The crack-up boom appears. Everybody is anxious to swap his money against "real" goods, no matter whether he needs them or not, no matter how much money he has to pay for them. Within a very short time, within a few weeks or even days, the things which were used as money are no longer used as media of exchange. They become scrap paper. Nobody wants to give away anything against them.”

In finale, my view of rising gold prices is that it reflects on a burgeoning global monetary disorder based on the incumbent operating currency platform (US dollar standard) more than simply bubble symptoms. It’s more than a narrative; it is an underlying degenerating malaise that places at risks faith in our money.

Although a gold bubble cycle CANNOT be discounted, we’d like to see evidences of a credit driven euphoria underpinning private or public sector acquisition. Absent credit expansion, which is the sine qua non fuel for any bubble, rising gold prices signify as a symptom.