A person of free intelligence who writes openly and without fear, and is generously angry with the prevailing falsehoods of the day. – Professor Peter Boettke

In this issue:

Phisix: 30+% Money Supply Growth Rate Now Seen in Official CPI Data

-Philippines’ Subsidy Politics: The Steady March to a Rice (Food) Crisis

-Why Rice Smuggling will Persists: Clue (politicians depend on them)

-30+% Money Supply Growth Rate Now Seen in Official CPI Data

-More on the Divergence Between Money Supply and Bank Loan Growth

-Philippine Hyped Economic Growth Story: Beware the Mean Reversion

-Bingo! BPO Growth Rates Tumbles Big

-Phisix: More Marking the Close, Manic Punts Amidst Slowing Volume

-The ECB Takes the ‘Euthanasia of the Rentier’ to Reality

Phisix: 30+% Money Supply Growth Rate Now Seen in Official CPI Data

My rice supplier increased prices of a sinandomeng 25 kg sack by another 4.16% this week. This marks the second price hike this year, the last time was just almost a month ago! This would also be the third increase in about a year.

Philippines’ Subsidy Politics: The Steady March to a Rice (Food) Crisis

My personal rice inflation experience seems consistent with recent national developments. Reports say that between January and April, “rice prices rose by 27 percent for regular milled variety in Metro Manila, vis-à-vis national average increase of 18 percent for the well-milled variety[1]”. Such developments have partly been imputed to global dynamics, as well as, to domestic factors supposedly due to ‘low inventories’ and high domestic energy prices.

Meanwhile, a government economic research agency, the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), noted that in 2013, milled rice increased spiked by 15% which they associate with “a decline in official rice imports” and not from “price manipulation by rice cartels.[2]” The agency attributes the deluge of “unofficial imports reached around one million tons” to the price arbitrage between local and global prices. Global rice prices as measured by the Oryza White Rice Index or “weighted average of global white rice export quote” grew by 5% last year.

Since 2009, unofficial imports has been estimated by domestic authorities at “80 million sacks or four million metric tons (MT)” with an estimated worth of P56 billion[3]

The Philippine government has been slated to import 800,000 metric tons from Vietnam this year, following last April’s bidding which was won by the government of Vietnam. Unfortunately some of Vietnam’s private exporters have officially been refusing to deliver rice supplies noting that “prices are too low to cover their expenses[4]”. They have announced plans to renegotiate with the National Food Authority (NFA).

As usual, both the government and mainstream media trace the unfolding events in the rice markets to superficial supply chain problems. Here, the PIDS fails to explain why the domestic prices have been ‘high’ from which incentivizes arbitraging that led to rampant rice smuggling. High domestic prices are products of underlying market, legal and institutional conditions. High prices don’t just occur for hardly any reason at all.

Let us dive into the economic picture.

From the demand side, whatever happened to the BSP’s aggregate domestic demand boosting policies? Whatever happened to all those cumulative expansion of banking credit loans which represents fresh spending power or injected demand that has been ventilated as 30+% money supply growth rates? How did the additional massive purchasing power influence rice and food prices? By shoring up a credit boom via new money flowing into the economic streams, how has these not led to increased consumption in terms of food?

How is it that when it comes to the dark side of the credit financed boom, demand suddenly exists in a vacuum?

How about the added demand derived from prices set artificially, not by the markets, but by political forces? How much of demand comes from such subsidies?

True, such subsidies have been meant to support the underprivilege, but at what costs? Are the underprivledged really benefiting from the policies?

And on the supply side, whatever happened also to the entrenched protectionist policies long embraced by the Philippine government? Won’t these raise internal costs of rice production? Whatever happened to all those subsidies thrown by the national government to the NFA?

Time to dig down into the details.

The agricultural industry has been benighted by both non-tariffs (e.g. quantitative restrictions) and tariffs barriers. For instance, high tariffs on onions, potatoes, garlic and cabbages have prompted for a proliferation of smuggling.

While the previous regime has partly opened rice importations to the private sector, instead of import quotas being awarded to the highest bidder, quotas has been granted to “choices” by the NFA authorities and by the national government. In other words, the outcome of the politicization of the distribution of quotas has been to reward “parties close to the agency or to the government in power”, according to local economist, professor and former National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) Director Gerardo Sicat[5].

Yet the same parties transform these quotas into “quick profits” by selling these to importers. Meanwhile, the failure by the government to collect the duties on rice imports from these importers becomes part of the unofficial imports.

So the government created their own predicament. First, they put up a high barrier against access to low priced agricultural products abroad. This has been intended to supposedly protect domestic farmers but comes at the expense of the Filipino consumer. Second, the government promotes inefficiency that raises cost of production and thereby reflecting on market prices. And third, they provide legal loopholes from which government and their cronies take advantage of or profit from.

But the buck doesn’t stop here.

The public choice dimension comes into play.

The politicization of the rice and agricultural markets has become a milking cow meant as “a convenient tool for public distribution of commodities” used to win electoral votes for incumbent politicians, wrote the former undersecretary of the Department of Agriculture Bruce Tolentino in a 2008 Wall Street Journal article[6]. He gives an example where “In 2006, the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee and the Committee on Agriculture and Food released a report that stated that in 2004, proceeds arising from fertilizer procurement and distribution helped finance the election campaign of President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.”

And the use of the NFA machinery for vote buying has not just been limited to top officials, but has been pervasive even from politicians at the local levels.

Yet the essence of cost of rice protectionism, Mr. Tolentino notes, has been the unintended consequence or the opposite the goals from which the whole institution has been established. (bold mine)

Not so in Manila, where succeeding presidents and NFA administrators have defended the NFA as necessary to shield rice farmers from low world prices and ensure stable supplies for consumers. Unfortunately, this policy has had exactly the opposite effect: The incomes of the Philippines's rice farmers have consistently ranked in the lowest quintile of the population, and domestic consumer rice prices are roughly double world prices. Worse, the NFA is now one of the largest drains on the nation's already precarious fiscal resources, requiring an annual subsidy of at least 1.2 billion Philippine pesos ($29 million) from national coffers, not to mention uncollected tariffs and opportunity losses due to price premiums borne by Filipino consumers.

In short, noble sounding but economically unviable programs have been used by politicians as cover to fulfill self-serving agenda.

So structural deficiencies in both the supply and demand side from the excessive politicization of the industry have, thus, resulted to HIGH domestic prices of rice.

Yet here is an update on the annual NFA subsidies and debts.

From the Philippine President’s Speech at the Congress on the 2013 budget[7]: This Administration will allot P7.4 billion for our banner rice program, while P1.5 billion and P1.75 billion will go to our corn and coconut development programs, respectively. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources will receive P4.6 billion, a sizeable increase from the P3.0-billion budget given them in 2012.

On NFA’s ballooning debt, from the Manila Standard[8] (bold mine): In the last year of the Arroyo administration, the NFA’s debt stood at P177.6 billion. In the first two years of the Aquino administration, the debts declined to P148 billion because it chose to tap the private sector, which shelled out the money for importation. As of December 2013, the NFA debt has ballooned to P173 billion. With this new 1 million metric tons at an estimated P20 billion, the NFA debt will surpass Arroyo’s record because the debt would soar to P197.6 billion,” the member, who sits also in the Economic Cabinet Cluster, told the Council.

Yet despite the increase in subsidies, the NFA continues to bleed. Accrued financial losses have reached Php 5.8 billion as of June 20, 2013. And because of insufficient funding for the subsidies, the NFA has resorted to borrowing money from the marketplace. The NFA’s capital deficiency has rapidly ballooned by nearly double from Php 75 billion to Php 143.75 billion says an NFA official[9].

In case you haven’t you noticed, on the surface, despite instituted political controls, rice prices have partly been adjusting to reflect on market conditions. But the symptoms of dislocations from the miscellany of political interventions (demand and supply side) have been surfacing via increased supply side strains compounded with the growing financial pressures on the government.

In addition, the above demonstrates of the subsidy nature that undergirds Philippine politics. However this comes in the context of the contributions by the heavily politicized agricultural industry, particularly, subsidies on demand as provided for by politically suppressed (agricultural) prices, subsidies on demand from the BSP’s inflationary boom, taxpayer and peso holder support to an intensely bloated bureaucracy, resource transfers to cronies channeled through arbitrarily determined rice import quotas, tacit backing to the political ambitions of incumbent politicians through the use of government (NFA) resources, and finally aid to the NFA’s debt build up via zero bound rates or financial repression policies.

This means that the current development in agricultural politics points to four scenarios: greater credit risks via intensifying debt accumulation, higher taxes, sustained increases in consumer price inflation (yes more rice inflation) or a mélange of the three.

All these are manifestations that the current system is UNSUSTAINABLE and will eventually breakdown in the fullness of time.

At the end of the day, unless the Philippine government allows the law of economics to work by liberalizing the agricultural-rice markets through the dismantling of legal protectionist barriers, Philippine residents should expect HIGHER rice and food inflation overtime and or BIGGER public debts.

So while there has been little apprehensions over rice supplies over the interim, such ballooning imbalances brought about by a jungle of interventionist policies, heightens the risks of not only a financial crisis but a FOOD crisis through the passage of time. Unfortunately these have largely been unnoticed by the public whom have been blindsided by the phony boom and by the bread and circuses populist politics.

In short, political choices encompassing the agricultural industry will postulate to a tradeoff between current short term populist convenience (mostly in favor of politicians and their cronies) and a sustainable and functioning system. But since politician’s hold on power is short term, so will be the responses.

Why Rice Smuggling will Persists: Clue (politicians depend on them)

And contrary to the popular perception that unofficial imports or smuggling is ‘evil’, the public fails to realize that smuggling represents a NATURAL market response to a repressive political-economic environment. Smuggling is part of the informal economy.

Imagine if estimates are correct where rice smuggled into the Philippines has totaled some 1 million tons a year since 2009, then this means smuggling has not only ADDED to supply but has also HELPED in containing rice price inflation!

Here are some back of the envelop numbers for rice economics in the Philippines.

The Philippines has reportedly achieved 97% rice ‘self-sufficiency’[10] where the gap between the demand and supply is what imports (official and unofficial) have been all about. The government imported 700,000 MT in 2013. For 2014, the programmed imports have been at 1.2 million MT where the earlier tranche of 400,000 MT has been tendered last December[11] and probably already shipped in. The balance of 800,000 MT represents the Vietnam project. The additional imports may be partly due to the aftermath of Typhoon Yolanda.

Thus rice smuggling competes with the official imports and or should serve as an excess or surplus buffer. In both ways, rice smuggling should help bring down rice prices. But rice prices have been increasing!

Despite the rhetoric of self-sufficiency, the Philippine government has either severely miscalculated on the economic balance of rice, and or, that such political programs has translated to massive ‘inefficiency’ where in both cases rice prices continue to spike. Yes production has increased alright but these came at a severe cost to the public as expressed in prices, these in spite of price controls!

As one would note from the above charts[12], instead of achieving either affordable rice prices and or to secure public security from the political programs of rice self-sufficiency, the inflation of rice prices has persisted over the long run, if not having to accelerate over the latter pre-Aquino administration years.

This so-called self-sufficiency political program has been a legacy from the tyrannical Marcos regime called ‘Masagana 99’[13], which has been carried over by different administrations since its inception.

Alternatively, we can deduce that without smuggling, perhaps the Philippines MAY have already realized a RICE/Food crisis. Rice smuggling, in short, helps politicians BUY time from the current unfeasible rice political economic regime.

Or might I propound a radical viewpoint: Rice smuggling signifies a veiled subsidy to politicians in terms of prolonging their tenure through the attainment of temporary social stability. The implication of which is that all these media based political clampdown on rice smuggling represents only entertainment value and or another publicity shtick designed to show the squeaky clean image of the incumbent government for the latter to attain their personal political goals. In reality, the incumbent government, as with their predecessors, depends on rice smuggling to make up for, and or to act as insurance against, their policy calculation errors and to keep public security intact. So despite all the demagoguery and media hysteria about political correctness, we should expect rice smuggling to persist.

Finally it’s also important to note that the reactions to higher domestic costs of rice production by Vietnamese farmers in resisting to deliver rice supplies to the NFA reveals of the disruptive effects of the current global inflation process in motion.

And more importantly, the self-inflicted obstacles in the industry also expose on the depth of sensitivity or vulnerability of the domestic food supply chain to exogenous factors, especially to an outbreak of global protectionism.

Fish see the bait, but not the hook; men see the profit, but not the peril. - Chinese Proverb

30+% Money Supply Growth Rate Now Seen in Official CPI Data

The rice inflation predicament has been more than just my personal suffering.

Today, this plays a significant role in the BSP’s current admission of a surge in consumer price inflation rates.

Philippine price inflation notes the Wall Street Journal “rose to its quickest pace since November 2011”. But “don’t worry be happy”, because this has supposedly been within the Philippine central bank, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ ambit, “CPI remains within the bank’s 3.0%-5.0% target range”[14]

You see central banks are never wrong. Since they make the statistics, they declare or impose on the public the reality which they desire to show. For instance in Argentina, the ‘decreed’ official inflation rate is at 10.98%, but despite the January rate hikes[15], annual implied inflation rates (as measured by Cato’s Troubled Currency Project) has zoomed back to now 38%! I say ‘decreed’ because local economists have been banned from saying otherwise.

Now the 4.5% inflation based on the BSP’s official statement[16] (bold mine): The continued uptick of headline inflation in May was attributed largely to higher food prices and electricity charges. Tight domestic supply conditions led to higher prices of key food items, particularly rice, meat, fish, milk, oils, and sugar. At the same time, higher spoilage during the summer season adversely affected domestic supply in the case of fruits and vegetables. Meanwhile, the increase in electricity rates as a result of higher generation charges in areas outside National Capital Region also contributed to the rise in non-food inflation.

Curiously again, the inflation problem swings to the supply side where demand, particularly demand based on credit inflation, has vaporized. Yet there has been no explanation what has caused the “tight domestic supply conditions”.

If you look at the BSP’s inflation details which I urge to do, you will notice that the inflation components have been broken down into 3 major categories: Food and Non-Alcoholic beverage (with a 38.98% weight), Alcoholic beverage and Tobacco (2% weight) and the biggest NON-Food items (constituting 58.99% weight).

The biggest member for Food grouping has been bread and cereals which accounts for 12.44% of total CPI index, from which the largest subclass has been rice at 8.92% share, again of the total CPI basket. [To emphasize, the statistics I mention here are weights relative to the BSP’s overall CPI model]

For the non-Food category, housing constitutes the largest share at 22.47% weight, with ‘actual rentals’ as a sub-category at 13.75% of the CPI basket.

Interestingly, if not surprisingly, a second biggest component in the non-Food segment has been ‘Restaurants and Miscellaneous Goods and Services’ with a 12.03% share. Catering services, which represent the biggest share of the said group accounts for 8.01% of the overall CPI pie.

I say “surprisingly”, because I never realized of the significance of the eating habits of the average residents would capture an influential share of the BSP’s inflation pie. The implication from the above goes like this: The average residents prefer to eat out or to have food catered at home even with their limited purchasing power. This is something that I will NEVER logically comprehend.

And given that the Restaurants (the means of selling food) are related to the Food index, then combined (catering services + Food index- non-alcoholic beverages) would amount to 44.3% share of BSP’s CPI model. If this represents the share of a household budget, then this statistics don’t fit mine. I am quite confident this won’t suit up to the lifestyles of many or if not a majority.

Let me further add, rice in a typical meal (one viand one cup of rice) at the informal food outlet would likely account for 20% of the total expenditure by a customer. In my personal observation, young male consumers of the informal economy food outlet tend to have more rice than viand. So the share of rice consumed per meal could be higher.

So even from the methodological construct perspective of the CPI basket alone, there seems little representativeness of the inflation data to the real world.

Yet rice inflation in the perspective of the BSP report—based on May—says 12.9% (year-on-year), 1% (month-on-month) and 11.5% January to April. The latter data greatly departs from the news I cited above where “national average increase of 18 percent for the well-milled variety”. That’s about 6.5% differentials!

Also the BSP notes of “higher prices of key food items, particularly rice, meat, fish, milk, oils, and sugar”. Unfortunately the BSP didn’t say that these are exactly areas covered by the Price Act (REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7581[17]). This means that these items have been monitored, regulated or under selective price controls by the government. This also means market price flexibility has been taken off the table. So instead of posting (black) market prices, the BSP will likely indicate the “regulated’ prices in their report. So the most likely ramification is that price inflation have been much HIGHER than indicated by the BSP’s report!

Another MORE interesting data is the housing segment called ‘actual rents’ which has a share of 13.75% of the CPI basket. The BSP rent data as of May registered 1.8% (y-o-y), .4% (m-o-m) and 1.7% (January to April). These figures don’t seem to fit with the property boom story!

I can only make anecdotal comparisons based on media’s report.

Based on office rentals (differentiated by grade and location), in 2014 the industry expects rental prices to advance by anywhere 4.4% to 8.2%. Supposedly due to ‘tight vacancy rates’, some developers will even be offering pre-leasing contracts.

For the low cost housing, the government has extended rent controls for 2 more years. The rent control policy limits annual rental prices increases to 7% for as long as these apply to same tenant occupied units[18]. The rent control covers units with rental prices below 10,000 pesos in the National Capital Region (NCR) and other urban areas. In the rural areas, the populist edict applies to rental units of 5,000 pesos and below.

As a side note, since rent controls preclude property owners from adjusting prices based on market realities (which essentially violates property rights of property owners), the economic outcome will be one of shortages in housing supply for these housing categories as depressed prices reduce the incentive to provide additional supplies. Another negative from rent control policies is the deterioration in the quality of rent spaces, which not only lead to the dilapidation or loss of worth the housing values, but importantly raises the specter of various housing risk hazards. For instance, why would a property owner spend to improve on his property’s safety when his income does not permit so?

Yet the consequent shortages of housing supply become part of the demand for ‘socialized housing’. So the problems (shortages) created by earlier interventions (rent control) result to more interventions (socialized housing). And as I previously noted[19] socialized housing contributes to the current housing bubble. So two wrongs make no right.

Of course, these would be pronounced, if rental control programs are strictly enforced.

Nonetheless even the minimum allowable price increases on the low cost housing rent reveals that the BSP’s data has been out of line with real developments.

Again as previously pointed out, even BSP officials know or admit that their inflation data are hardly an accurate representation of reality. Here is a reprise of a quote from BSP Deputy Governor Diwa C Guinigundo’s paper published at the Bank of international Settlements[20] (bold mine)

Excluding asset price components from headline inflation also has little effect. Currently, the CPI includes only rent and minor repairs. The rent component of the CPI is, however, not reflective of the market price because of rent control legislation. The absence of a real estate price index (REPI) reflects valuation problems, owing largely to the institutional gaps in property valuation and taxation. While the price deflator derived from the gross value added from ownership of dwellings and real estate could represent real property price, it is also subject to frequent revisions, making it difficult to forecast inflation.

To repeat: Not REFLECTIVE of the market price because of rent control legislation, see what I mean?

Notice too in the BSP annualized CPI inflation figures for May 2014, only 2 sectors posted negative growth, specifically, Transport services (-.1%) and telephone and telefax equipment (-.7%)—the latter seems as sign of obsolescence, whereas significant categories in the BSP model have registered growth numbers north of 2%.

You see, the nasty side effects of the 30+% money supply growth rate have now become more visible as I have repeatedly been warning about here.

Four implications from these:

1) Higher input prices will CRIMP or COMPRESS on corporate profits.

2) Rising CPI means a redistribution of expenditures by households which would mean DIMINISHED disposable income, thereby constricting demand.

3) Higher inflation rates will also mean HIGHER interest rates which again will add to the pressures of servicing debt. This will compound on the strains on profit margins, as well as, increase credit risks for highly leveraged entities. Higher debt service will also REDUCE the incentive to expand capital expenditures which also squeezes demand.

4) The last but most important would be the repercussions from these three dynamics: That the aggregate demand policies of credit expansion that has fueled economic and financial speculation aimed at attaining a “quasi-permanent boom” may now be in jeopardy.

As a side note, it has even been possible that the initial toll from all these has resulted to a drop in the 1st quarter GDP growth rate to 5.7% from the former 6-7% levels, which went against the consensus expectations. This ‘surprising’ slowdown has been blamed by the government on Typhoon Yolanda as a ‘one-off’ or anomalous event which popular opinion swallowed hook, line and sinker. Yet ironically, the only direct connection between the lackluster GDP performance in the 1Q 2014 and Typhoon Yolanda has been in the coconut industry![22] A secondary factor has been pinned to the supposed tightening by the BSP. But as I have pointed above, an increase in general banking loans growth rate of 18.9% in April from 18.1% in March (y-o-y) represents some tightening eh?

More on the Divergence Between Money Supply and Bank Loan Growth

Back to the growing divergence between money supply-loan growth performance; yet if my suspicion is anywhere accurate, then this indicates that highly leveraged firms or institutions may have reached their “saturation” levels in terms of debt absorption. The diminishing law of returns of debt relative to output means that more debt is required to produce a unit output. But of course, there are limits to such debt financed debt rollover which squarely depends on low interest rates and the burden from the level of debt itself. Since debt is used to pay for existing debt, then this means mounting debt burdens.

If existing highly levered companies can’t produce growth from every marginal new debt acquired, then either the government will have to make up for the slack, or the banking system would need to attract more participants to borrow to cover up on the deficiency.

However, none of the prospective gap filling measures to juice up the statistical economy removes the aspect of rising risks from a potential disorderly unwind from highly leveraged companies. Yet the seeming increasing use of debt IN-debt OUT (Ponzi financing) operations by more firms only highlights on the intensifying degree of the vulnerability and sensitivity to interest rate adjustments that has been building up on the system.

And because of the limited penetration level of the banking system, this won’t be obvious in general debt data. But this will be apparent on a per company basis.

[As a side note, bubble worshipers always love to keep using debt data of other nations to compare with the Philippines and declare a free pass on current debt conditions. Again these are apples to oranges comparison, primarily because of the many structural distinctions such as bank penetration level, legal institutions, size of markets, culture and etc…. They should rather look at the data during the 1997 Asian Crisis and see how despite low levels, the crisis buffeted the Philippines. And as I previously wrote[23], debt tolerance level differs from country to country as seen when a crisis hit. Even during the onset of the Asian crisis, statistical figures like bank lending to the property sector, property exposure and non-performing loans or even vacancy rates had all been different for ASEAN nations. The Philippines has generally the “lowest” among all these variables. Paradoxically lowest does NOT translate to immunity.]

There are already pressures being applied on the BSP to raise rates such as the HSBC.

But considering how the government has been acutely hooked to the stimulus, I have reservations if the BSP will submit to such pressures.

The BSP appears to have pulled the proverbial “wool over the eyes” of the markets by recently raising reserve requirements twice. They further claim their raising of reserve requirements have allegedly “siphoned some $2.7 billion from the system”[24]. Yet banking loans growth in April increased by Php 556.318 billion (nominal, y-o-y). At USD-peso of 43.5 this would mean an increase of US $ 12.789 billion. So I really don’t know where such siphoning took place. They can’t blame it on liquidity because liquidity has been slowing since January even before the reserve requirement changes.

Also, according to modern central bank operations, reserves are today “supplied” by the central banks, rather than the banking system adjusting to the changes in mandated reserves. This basically means that reserves don’t serve as a constraint to bank lending, unless the BSP operates in an archaic system.

The BSP, like the supposed reserve requirement tool or like the flagrant disregard of their self-imposed 20% banking loan cap to the real estate industry, will likely use policy tool “stunts” or smokescreens to sustain the status quo which essentially neglects the risks being amassed in the system.

Yet even if the BSP does raise rates, which will likely be minimal, I expect an initial jump in the demand for loans as the market will likely race to lock in loans at short term rates.

Nevertheless, it will be interesting to see how the government and the BSP whom has been applying self-contradictory measures, on the one hand, price inflation suppression through the massaging of financial markets, statistical camouflages, publicity flimflam and even price controls in the real economy, while on the other hand, encouraging (or doing little to control or stem) a bank lending based boom. Yet these two forces are incompatible. One of them will be exposed for their artificiality…soon

Philippine Hyped Economic Growth Story: Beware the Mean Reversion

Let me add to my act as the unpopular spoiler of this boom.

In near unanimity, the public has acquiesced to the narrative that the slowdown in 1Q 2014 annualized growth rates have been an aberration as explained above.

Unfortunately for popular wisdom, there is a possible non-economic, but financial-statistical force lurking behind the shadows. This is called the regression/reversion to the mean.

Mean reversion is a theory suggesting that prices and returns eventually move back towards the mean or average[25]

The above represents the Philippine annual GDP based on different frames.

It’s a sad reality that the public will not set aside their blinders from their impassioned belief of the perpetuity of this bogus boom, so no matter the facts or the theory they will just disregard anything that goes against their deeply held belief.

Nevertheless from an objective perspective, even by just looking at mere statistical figures, one would come to realize that the economic growth rate decline of 1Q 2014 represents the following:

1) It’s NOT an aberration or anomaly. From the peak growth at 7.9% in the 2nd quarter of 2013, the recent slowdown signifies the THIRD quarter of decline (topmost chart). Simply put, there were other two growth rate retracements ahead of this quarter.

2) The reaction has been SENSATIONALIST. Here are the growth rates during the past 4 quarters in percent: 7.9 (2q13), 7.0 (3q13), 6.3 (4q13) and 5.7 (1q14). The differentials seen by quarters: -.9% (3q-2q), -.7% (4q-3q) and -.6% (1q14-4q13). The rate of decline during this quarter (-.6%) hasn’t even been as significant as the initial drop a quarter past the apogee (-.9%). Yet the ferocity of denial

3) This time IS NOT different. Recent events back this up. In 2010, the statistical economy’s annualized growth rate jumped to a stunning high of 8.9%, before falling back to 3 to 4% until 1q of 2012 (middle window)

4) The slowdown looks MOST likely a REVERSION to the MEAN.

Tradingeconomics.com says that the average growth rate of the Philippine economy from 2001 until 2014 has been at 5.04%.

Outside the 2013 7.9% growth, there have been three times during the past 13 years where statistical economic growth reached 7% and beyond, yet all three failed to sustain their ‘peak’ levels. The current trend looks like history replaying itself. (lowest pane)

Here is a short chronicle.

In 2004, 7% growth rates were posted in two consecutive quarters, particularly 7.1% (2q) and 7.2% (3q), but the growth rates receded back to 4.5-5.5% through 2006. By the same token in 2007, the economy’s growth rates picked up and reaccelerated. Growth rates zoomed past 6%, and climaxed at 8.3% (2q). But law of mean reversion flexed its muscles. Growth rates went downhill and nearly fell into a negative zone during the last 3 quarters of 2009, specifically 1% (2q), 1.6% (3q) and .5% (4q).

The above figures reveal of slightly nuanced perspectives offered by different time frames but they end up with a similar conclusion: The 7-8% growth rates are UNLIKELY a NEW Normal but outliers subject to the reversion to the mean.

Notice that I strictly focused on numbers without interjecting economic-political extrapolations.

Now for the economic context: The downturn of 2008-9 has been in response to the US epicenter induced global financial crisis. The BSP has used this global crisis as justification for the grand pirouette towards a bubble economy via aggregate demand-quasi permanent boom policies. The declines from the 2010’s highs hardly emanated from external factors (even when the Euro Crisis emerged).

The recent 3 successive quarters of slackening from post 2013 highs, ironically emerged alongside the 30+% money supply growth rates. This means that exploding growth rates of debt which has been ventilated through money supply growth rates, has been producing less and less of economic output—diminishing returns of debt (again as discussed above)

If the laws of the regression/reversion to the mean will be followed (even without economic interpolation) then statistical economic growth will most likely surprise the mainstream NEGATIVELY as economic growth are south bound in the coming one or two years, with probable interim bounces.

Another way to look at this is if history does rhyme, then it means a big, big, big disappointment for the consensus bearing exceptionally high expectations.

Oh yes, the inflation (stagflation) story alone represents a huge headwind to real economic growth. Compounded with a bubble cycle, these twin lethal forces would fluidly dovetail with the reversion to the mean.

One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back. - Carl Sagan

Bingo! BPO Growth Rates Tumbles Big

In questioning the sustainability of the shopping mall boom, last year I opined that one sunrise area, the BPO industry, will hardly sustain its robust growth trend enough to support consumer demand.

Nevertheless, where I believe they gone astray is that they have ignored the S-Curve cycle of the technology industry..

In short, unless there will be assimilation of more productivity through newer innovation, the industry’s growth diffusion levels, as it ages, is bound to slowdown. I have used this curve to rightly predict the slowdown in telecom penetration levels.

The BSP notes of a substantial decline in the growth rate of the BPO industry[27] (bole mine): The country’s IT-BPO services industry remained robust in 2012, as shown by the results of the Survey of Information Technology-Business Process Outsourcing (IT-BPO) Services conducted by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). Revenues from the industry continued to register double-digit growth during the year, albeit at a decelerated rate of 11.4 percent compared to the 20.1 percent posted in 2011. Total revenues of the industry rose to US$13.5 billion in 2012 from US$12.1 billion in the previous year.

Bingo again!

IF the declining growth rates in the BPO sector will be sustained, then this will not just affect the consumer demand, more importantly, this will slam hardest the vertical ‘office’ real estate industry.

Many aggressive capex of vertical real estate projects have banked on the BPO’s astronomical sustained rate of growth. Yet as growth slows, so will demand. Unfortunately many projects have already been committed based on such Pollyannaish expectations.

Massive miscalculation expressed as malinvestments translates to coming massive losses.

Phisix: More Marking the Close, Manic Punts Amidst Slowing Volume

As I have been saying, the convictions of a one way trade have been so strong in such a way that any profit taking will be seen as buying opportunities. In other words, retracements appear as political incorrect and impermissible.

The excessively overvalued and technically overbought Phisix came close to neutralizing last week’s 2.4% decline with this week’s 1.73% leap.

Of course, part of this week’s gains has been attained by the massaging of the Phisix benchmark index levels.

This is a minor incident anyway, but it shows how desperate the bulls have become in employing price fixing measures which seems to have become a regular fixture.

Last Thursday, the Phisix (left window, chart from colfinancial.com) spent most of the day in the red, down by about .2+%. Well that was until the last minute where Phisix closed unchanged. Much of the last minute counterbalancing push has been via the Holding sector (right). The financials and industrials participated too (not in chart) but not as much as the star of the day, the holding sector.

One of the most interesting developments has been the unfolding manic sentiment conspicuously seen in the Philippine Stock Exchange’s market internals.

Daily number of trades (averaged weekly, left window) has declined during last weeks’ profit taking but not enough to go below the May 2013 levels where the Phisix traded at the record highs of 7,400. This week’s rebound has apparently rekindled the feverish speculator’s sentiments where second and third tier issues has been bidded up along with Phisix heavyweights

Nonetheless the rebound in the Phisix comes with declining volume (based on the average weekly peso volume/average weekly number of trades). In short, bullish conviction has been strong alright, but the strength of which has been directed on mostly smaller and illiquid issues.

But the bullish backdrop on the general market has hardly been strong enough to be backed by volume. Instead, the declining Peso per trade volume suggests of weakening foundations for the current run-up.

The ECB Takes the ‘Euthanasia of the Rentier’ to Reality

It’s an extreme curiosity to see how the average citizens of the world have been treated by central bankers as some kind of guinea pigs subject to their social engineering experiments. These unelected bureaucrats seem to have little qualms on their experiments because they bear little cost on them. In short, these bureaucrats have little skin on the game. And the burden or price from such failures will be carried by the hapless guinea pigs, us, through debt/currency crisis from boom bust cycles and through inflation.

Even the variations of credit easing policies tried and tested by various developed economies have hardly brought any real economic recovery back to the forefront. And this is why governments via central banks have increasingly been pushing monetary experiments to its limits.

What this has instead produced has been a massive redistribution or transfer of wealth from the currency holders to asset owners or what we may call as reverse Robin Hood. Importantly what all these have racked up has been a massive asset bubbles and unsustainable debt all over the world.

The Wall Streets of the World, particularly in the developed economies wildly cheered and celebrated the latest aggressive move by the European Central Bank’s Mario Draghi to drive down bank deposit rates into negative territory combined with a 4 year Targeted Long Term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO) and a prospective asset purchasing foray on Asset Backed Securities[28], thus according to the mainstream the ushering in of a “new era of negative interest rates”.

This in essence would mark a dream a come true or the realization of the “euthanasia of rentier” as advocated by chief inflation proponent John Maynard Keynes[29].

Yet instead of practical men…who are usually slaves of some defunct economist as Mr. Keynes once remarked, ECB’s Mario Draghi seems to have perfected what Mr. Keynes says of slaves of some defunct economist but not as a practical man but as “madmen in authority”.

The Negative Deposit Rates is said “to apply to reserve holding in excess of the minimum reserve requirements”[30].

Banks hold reserves in order to ensure payment to depositors on demand. By penalizing banks for keeping reserves with the central banks, in effect, banks will now be forced to reduce reserves and to indulge in greater risks of impairing their balance sheets by either issuing risky loans or by wantonly engaging in more asset speculations.

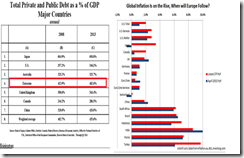

In addition, the ECB’s response to supposedly a low-flation problem has been to force banks into lending even when the recent crisis has ballooned rather than caused a de-leveraging in her banking system. The Eurozone’s public and private debt relative to the GDP has inflated to 462.6% in 2013 from 413.9% in 2008 (left window)

Despite the magical effect of Draghi’s “do whatever it takes to save the euro” of reviving the convergence trade in Europe’s periphery bonds, there has been little recovery in bank lending activities and even in the real economy.

The Keynesian authorities and their followers fail to see that this has been a balance sheet problem. Euro banks hesitate to lend because of still impaired assets due to the previous days of reckless lending and due to the lack of creditworthiness of borrowers. Euro banks know that their balance sheets have been artificially propped up by money printing by global central banks. On the other hand, companies in Europe’s periphery hardly invest because of poor prospects of investment returns and or that they already have borne heavy yokes of debt. Meanwhile households of the Eurozone has exhausted on their borrowing capacity. So overleverage has been the problem and remains the problem for the Eurozone.

The ECB’s actions extrapolate to even more striking imbalances ahead. As fund manager and analyst Doug Noland of the Credit Bubble Bulletin observed[31], (bold mine)

The markets foresee only more central bank liquidity making its way to enticing market Bubbles. Italian 10-year sovereign yields sank 20 bps points this week to a record low 2.76%. Imagine a country with complete economic stagnation and debt-to-GDP approaching 130% - and borrowing at yields below 3%. This week saw Spain’s yields sink another 22 bps to a record low 2.63%. Portuguese yields sank 11 bps to a near-record low 3.52%. With mounting debt and deep economic problems, French yields ended the week at 1.70%. A strong case can be made that the European debt Bubble has inflated into one of history’s greatest mispricings of debt securities. European bonds – and global risk markets more generally – are showing signs of upside dislocation – likely spurred by derivatives and speculative trades gone haywire. The “global government finance Bubble” thesis finds added confirmation on a weekly basis.

I would add carry trades to this[32], especially with the ECB’s recent action.

In sum, the ECB has been attempting to solve her debt problems by gorging on even more debt. As I have repeatedly analogized, this would be similar to solving drug dependence or addiction with even MORE drugs!

Yet it’s no guarantee that forcing money out of the banking system will find their way into spending via credit expansion. And this is why experts like Kenneth Rogoff have recently suggested for governments to embrace a cashless society[33] in the fear that people may hoard cash instead. Experts would like governments to grab outright control of everyone’s money!

While the ECB’s new era of easing may propel asset markets like stocks higher over the interim, the alternative is that this may abet propagating “inflation” on a global scale.

Yet given severely overvalued and overstretched asset markets, I am doubtful if these central bank induced boom can last.

And global price inflation rates have already been picking up for most of the world including the US (see right pane, chart from SNBCHF).

In the Eurozone, German and French inflation has been little changed from 2013. It’s only in the crisis afflicted peripheries where low-flation has been apparent.

Again should consumer price inflation continue to accelerate, this will be incompatible with the sustainability of debt financed asset bubble boom.

Moreover, given the simmering inflation and debt problems in Asia, I certainly am in doubt if they can join the US-ECB asset market shindig for long.

Even Malaysia’s hybrid national sovereign fund and private investment vehicle, the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) has more than just debt problems where cash flow from her generic businesses can only finance 53% of interest payments, so 1MDB has basically embraced what Hyman Minsky has warned as Ponzi financing or DEBT IN DEBT OUT[34].

As you can see wherever you glance there are more problems or risks than opportunities presented.

Bottom line: negative deposit rates means that we should brace for a global crisis in a not so distant future.

Human beings have a natural tendency to ignore obvious warning signs and take the path of least resistance. It’s a much simpler prospect to stick our heads in the sand than to acknowledge uncomfortable truths and risks.—Simon Black

[17] Department of Trade and Industry The Price Act of July 1992 REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7581 AN ACT PROVIDING PROTECTION TO CONSUMERS BY STABILIZING THE PRICES OF BASIC NECESSITIES AND PRIME COMMODITIES AND BY PRESCRIBING MEASURES AGAINST UNDUE PRICE INCREASES DURING EMERGENCY SITUATIONS AND LIKE OCCASIONS…Price ACT…1. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE (A) Basic Necessities • rice • corn • cooking oil • fresh, dried fish and other marine products • fresh eggs • fresh pork, beef and poultry meat • fresh milk • fresh vegetables • root crops • sugar

[24] Wall Street Journal Blog, loc cit