Anyone who looked only at the index of prices would see no reason to suspect any material degree of inflation; whilst anyone who looked only at the total volume of bank credit and the prices of common stocks would have been convinced of the presence of inflation actual or impending. For my own part, I took the view at the time that there was no inflation in the sense in which I use this term. Looking back in the light of fuller statistical information than was then available, I believe that while there was probability no material inflation up to the end of 1927, a genuine inflation developed some time between that date and the summer of 1929—John Maynard Keynes

In this issue:

Phisix Melts Up as Money Supply Growth Sizzles for the Eight Month

-Statistical Growth: Lather Rinse and Repeat

-BSP’s Price Inflation and Credit Growth Bait-and-Switch

-The Correlation between the Phisix and Banking Loans to Financial Intermediation

-Philippine Peso: The Argentine Paradigm

-Differentiating the Philippines from Argentina

-What A Replay of the 2013 Mania Means

-Celestially Valued Issues Are Soon Earth Bound

Phisix Melts Up as Money Supply Growth Sizzles for the Eight Month

Statistical Growth: Lather Rinse and Repeat

When the Philippine government raves about economic growth, they rhapsodize about the “consumer economy”[1], and subsequently, the underlying support that industries have provided to them. For mainstream media, such has all been ‘lather, rinse and repeat’.

Yet there has been little investigative work on how such supposed ‘robust’ growth have been attained or how this has led to asymmetrically or unevenly distributed growth, that has concentrated benefits (as well as risks) to select sectors and how these industries have been financed.

Importantly there have hardly been attempts to scrutinize at the accuracy and representativeness of statistical growth data with the real economy. For instance, during the latest peso meltdown which came amidst supposed strong external account data, smuggling has been raised by the bewildered consensus as one of the culprit.

And the same dynamics hold when the government and chieftains from the industry benefiting from the supposed boom parrot the so-called demand side growth. Remittances, BPOs, trade, and foreigners have been popularly thought as providing the bulwark of the so-called demand. And once again for mainstream media, this has been ‘wash, rinse and repeat’.

The general impression have been that Filipino consumers have unlimited spending power. And because of such perceived permanence of infiniteness, the bulk of statistical economic growth has emerged from select industries, who have indulged in a wild and ridiculous pursuit to satisfy such ‘demand’, and thus the ‘lopsided’ growth.

For the consensus, demand has been visible but supply has been invisible. Never mind the spectacular rate of growth in the supply side in order to chase the highly touted consumer demand. For the consensus supply has little impact on demand.

Paradoxically, when the government talks about price inflation, demand becomes invisible.

From the latest inflation data by the Philippine central bank, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP)[2], “The continued deceleration of headline inflation in March was traced mainly to the slower increases in the prices of non-food items. This was attributed to the downward adjustment in electricity charges and price reductions in LPG and kerosene products. By contrast, food inflation increased slightly as most food commodities, particularly rice, meat, fruits, and oils posted higher prices due to limited domestic supply.”

So for the mainstream media and for the consensus experts, price inflation has strictly been a function of supply. Lather, rinse and repeat. All of a sudden, the consumer economy evaporates in thin air.

So when perusing at mainstream discussions or literatures there has been a predominance of selective perceptions (ignoring opposing messages) or magnificently huge blind spots (biased perspectives).

The important message conveyed here is that statistical growth is seen as a politically correct theme. And to go against this populist tide has been perceived as sacrilege.

BSP’s Price Inflation and Credit Growth Bait-and-Switch

But such populist sentiment is now in jeopardy.

I asked last week if the crash of the Peso a few weeks back and the BSP’s raising of reserve requirements was in response to the anticipation of the M3 (domestic liquidity) data—“Could it be that the Philippine currency and the Philippine treasury markets have both been anticipating another 30++% M3 growth??? Has the BSP’s response also been in reaction to the coming report?”[3]

The BSP’s latest report appears to reinforce my suspicions. Let’s read it straight from the BSP[4]…[bold mine]

Domestic liquidity (M3) grew by 36.4 percent year-on-year at end-February 2014 to reach P6.9 trillion. This increase was slower than the revised 37.3-percent expansion recorded in January. Month-on-month, seasonally-adjusted M3 rose slightly by 0.9 percent, following the revised 5.1-percent growth in the previous month.Money supply continued to expand due to the sustained demand for credit in the domestic economy. Domestic claims rose by 14.3 percent in February as bank lending accelerated further, with the bulk going to real estate, renting, and business services, utilities, wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing, as well as financial services.

Didn’t you notice, domestic liquidity abruptly transformed into a ‘demand’ issue—particularly demand for credit? The seeming bait-and-switch in 2 different reports suggests that price inflation (said as supply side) has been uncorrelated—or of more importance—have little or no causal relationship with credit growth (said as demand side).

Some relevant statistics first: the banking sector’s claims on the non-financial private sector and other financial corporations constitute 67.93% of February’s M3. The banking sector’s claim on the national government (NG) net of deposit stands at 16.5% while the rest has been distributed to “state and local government” and to “public nonfinancial corporations”. Note: BSP’s money supply excludes demand deposit by the National Government, and holdings of “checks and other cash items” and “Interbank deposits” by other depository corporations[5].

The growth in money supply, as defined by the National Statistical Coordination Board, “consist of currency in circulation and peso deposits subject to check of the monetary system. Also called Narrow Money” In short, money supply growth is simply growth of money in circulation. So the dramatic growth in money supply has mainly been brought about by a credit boom to specific industries.

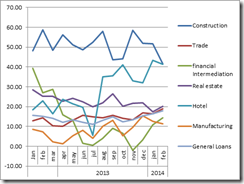

As shown above, even while the annualized rate of the construction sector has slowed in February to 41.59% from January’s 51.67%, the astounding growth rate by the other bubble sectors[6] namely hotel (41.33%), real estate (20.25%) and specially the financial intermediation (14.46%) have essentially offset the construction sector’s decline. The rate of growth from these industries has lifted overall banking loans.

Most importantly, banking loans to these bubble industries have now crossed the 50% threshold; specifically 50.46% as of the February. This is from 49.61% at the end of 2013. The fast expanding share of banking loans to these sectors proves my point of the increasing concentration of credit risks assimilated by the banking industry.

Then I wrote[7], (bold original)

The point of the above exercise is to show the size and scale of banking exposure on a significant critical segment of the statistical economy. In short, a bubble bust will tend to have a major direct impact on the statistical economy, aside from the potential contagion…Yet what appear as quite disturbing have been in the growth figures of the construction, real estate and hotel industries. For every 1.9 pesos of loans acquired by the real estate sector generated only 1 peso of additional growth. More staggering has been the proportionality of each peso growth for the construction and the hotel industry that has been financed by borrowings of 3.25 pesos and 2.7 pesos respectively.

Although not generally in a bubble, I always include the manufacturing sector, because some segments of the manufacturing sector may have participated in the supply to the bubble industries of certain goods, e.g. basic metals and fabricated metals, and etc…

And yet the incredible surge in banking sector loans have ballooned the banking system’s deposits by 36.2% in 2013. The tremendous rate of bank lending growth which is being reflected on money supply, should also reflect on bank deposits. [As a side note: I may have implied that deposits have been created at the receiving end, let me restate that banking loans (money from thin air) are credited as deposits to bank accounts of borrowers—particularly demand deposits—before such proceeds are spent into the economy.]

This brings us back to the seeming bait-and-switch where price inflation (said as supply side) have been alluded as having little or no causal relationship with credit growth (said as demand side).

What does credit growth mean? Credit growth simply means additional purchasing power, which will be spent or allocated in the real economy. The fantastic rate of money supply (circulation) growth is just a symptom of such rapid pace of demand from credit growth.

At 30++% growth of credit, this extrapolates to more than 3x growth in the statistical economy. This won’t be a problem if domestic supplies will grow enough to cover such incredible amount of rate of spending growth or demand. But 30++% money supply growth vis-à-vis 7% statistical economic growth implies that there has already been an immense variability between the rate of growth in spending and the available quantity of goods and services. This implies an intensification of price inflation.

Moreover, bubble areas have been rapidly building edifices to service mostly consumer demand, e.g. hotels, shopping malls and residential units. But upstream (higher order) producers, say cement, construction equipment and tools, bolts and nuts, etc…, have not coped up with the increase in the demand for goods that are required for the property boom. This again implies of a deepening of relative price inflation that has already been percolating into the real economy.

Of course the firms can opt to source such requirements abroad. But the problem is that if the Philippines do not expand exports enough to pay for ballooning imports, then trade deficits can be expected to widen which will corrode on her current account (surplus), and consequently, the Balance of Payment (BOP) standings. The broadening of trade deficits will have to be financed by other means. If there won’t be sufficient capital flows or financing from elsewhere, then the Philippine government will likely run down her on much vaunted foreign exchange reserves. So a sustained dependence on imports in order to service the huge credit driven domestic demand growth will imply of a decline in the BOP conditions which also extrapolates to a lower peso. This is aside from the relative quantity of money growth.

And as I have been pointing out, we shouldn’t expect material improvements in domestic export industry even amidst a weak peso environment due to substantial resources already committed by a large segment of the formal economy in the redirection of their efforts towards bubble blowing industries rather than to the production for exports. In short, current easy monetary policies have incented a shift in the Philippine economy’s production structure favoring bubble industries at the expense of external trade.

And a decline in the peso will also impact domestic prices which will affect the allocation of goods and services. As I previously wrote[8],

Even if sourced locally, if the demand surpasses available stocks then prices will rise. And rising domestic prices will likely push domestic companies to seek relatively affordable alternative sources from abroadBut the latter window will now be closing. The falling peso should mean higher priced imports. And the slumping peso will even impact more supplies with limited competition or availability from domestic sources. Eventually high prices will increase project costing of companies and thus reduce demand or expansion

And both 30++% money supply growth and a falling peso will function as a 1-2 punch against the local real economy. As I said last week, a feedback loop mechanism between domestic inflationary forces with the falling peso has been progressively intensifying.

So despite the BSP’s signaling channel tactic of employing the Talisman effect—cite the recent reduction in statistical inflation—to ward off the “inflation” spirits, we should expect price inflation in the real economy to magnify overtime. Put bluntly, the BSP hopes that statistics will subvert the fundamental economic laws.

The US dollar-Philippine rose by .13% to 44.94 this week from last week’s 44.88. Yields of Local Currency Unit 10 year treasuries fell by 5.2 basis points to 4.419% from 4.471%. Yet we cannot discount any temporal relief rallies in both the peso and the treasury markets mainly due to interventions and secondarily from the interim RISK ON mode.

Remember Philippine treasury markets have not only been an illiquid market but have been tightly controlled by the government and their cohorts, the banking sector. I also expect the BSP to deploy some of their forex reserves rather than use the interest rate tool to keep the financial repression stimulus for the government ongoing.

So even if we go by the mainstream definition where price inflation represents an “an increase in the price of a standardized good/service or a basket of goods/services over a specific period of time (usually one year)”[9] such price changes manifesting symptoms of monetary inflation represents an expression “of the value judgments of the individuals involved” according to the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises in the “the special conditions of the concrete act of exchange”[10]. Also prices reflect “not only a division of labor”, according to another great Austrian economist F. A. Hayek, “but also a coördinated utilization of resources based on an equally divided knowledge has become possible”[11].

The bottom line is that credit growth will affect prices in the economy and markets.

The Correlation between the Phisix and Banking Loans to Financial Intermediation

Monetary or credit inflation affects the economy with a relative time lag. But when credit is used to push up the asset markets, the effects have the tendency to be more immediate. In the US, record stock markets have been accompanied by record margin debt.

Since the Philippines have no official data on margin debt for the stock market, I rely instead on the bank growth data to the financial intermediation sector as proxy.

The undulations from the trend of the annualized growth rate of financial intermediation banking credit seem to reveal signs of consonance with the month end Phisix data. The rebound in the Phisix last November coincides with the resurgence of bank credit to the financial intermediaries. Growth rate of bank lending to financial intermediaries in February was at 14.46% from January’s 10.89% or an amazing 32.8% jump.

[note: I initially planned to use average close per month for the Phisix which should exhibit a more elaborate picture but due to time constrains I had to use the month end to align with BSP’s data.]

While correlation is not causation, it is not farfetched to see that some of the sector’s loaned money may have been used to bid up prices of Philippine equities.

Philippine Peso: The Argentine Paradigm

This brings us back to the 30++% M3 growth.

Mainstream media backed by the consensus has been implying that due to the current boom the Philippines have been on path to become a developed economy.

Unfortunately, current policies and market’s behavior in response to such policies tell us otherwise. Instead we seem to be headed towards the Argentina paradigm.

February’s annualized 36.4% in M3 growth represents a stunning EIGHT months of over 30% growth which began in July 2013!!! These are facts based on BSP data.

Unless the BSP’s statistics is wrong (hopefully it is—which should be good news), the Philippines has been massively inflating faster than Argentina—in current terms and when the latter began to use the printing press to finance the lavish spending by the government in 2009-2010, as shown by the World Bank’s Money and quasi money growth (annual %) with my embossed updates.

Argentina’s money supply expansion has backed off to 27% in November of 2013 from a high of 38% a year ago[12]. Yet in 2010 when Argentina’s money supply rate hit more than 30%, this immediately fell back to the mid 20s before another resurgence in 2012. In other words, while Argentina money supply growth rate has been sturdily up over the past 4 years, money supply growth of over 30% hardly lasted for successive months.

The Philippines has EIGHT successive months of over 30% in M3 growth from the last semester of 2013 until the present!

Of course there are structural differences between the Argentine and the Philippines’ political economy.

The government of Argentina defaulted on her debt in December 2001. The debt restructuring has been an ongoing process[13]. The Argentine President Mrs. Cristina Kirchner, can even hardly use the Presidential airplane, the Tango I, for international travels because of the risks of being impounded due to legal disputes with Vulture funds as legacy to the 2001 debt crisis[14]. This is a revelation of Argentina’s dire financial conditions.

In other words, because of the lack of access to credit, the government of Argentina has used the printing press to finance her increasingly socialist spendthrift government.

Since coming into office in 2007, the Kirchner regime has nationalized 7 companies[15] which includes the nearly $30 billion private sector pension funds in 2008[16]. So by nationalizing pension funds the Kirchner regime virtually gained access to private sector savings held by these funds. But of course such has never enough for insatiable governments.

So to stem capital flight and to synthetically address price inflation, the Kirchner government has imposed various commercial restrictions via imports controls (including books[17] supposedly due to health concerns), currency-capital controls and even price controls. When the Argentine government devalued by more than 10% in January 2014[18] while simultaneously raising interest rates, the Kirchner government eased some of the currency controls[19]. There are presently almost 200 supermarket items under price controls[20].

So by stoking demand from the government printing press, via 25-30+% monetary expansion, while at the simultaneously restricting supplies via assorted controls, the result has been serious stagflation.

The government has essentially censored the economic industry by threats of jail terms for those questioning the validity or by those who reports on inflation figures outside the announced numbers by the government[21]. The former central bank president Mercedes Marcó del Pont even ridiculously argued that printing money does not lead to inflation[22].

So one cannot just rely on Argentina’s vastly manipulated government statistics, all one has to do is to look at Argentina’s credit ratings, interest rate levels, and credit default swaps to see the Kirchner’s regime growing desperation for funds.

A better picture has been the difference between the Argentine pesos’ official and black market rates. Since the Argentine government has ramped up on the use of the printing press in 2009, the Argentine peso has basically been in a rapid descent or in a collapse. While official inflation rates have been at 10.93% (December 2013), Cato Institute’s Troubled Currency Projects estimates Argentina’s inflation at 32%[23].

Argentina’s stock market benchmark the Merval which is at record highs may perhaps be indicating that the Argentina economy could be in the fringes of hyperinflation. In hyperinflationary episodes, people seek the safety of their savings (store of value) in stocks. In the case of Zimbabwe, thousands in % of returns in stocks only maintained a purchasing power of three eggs, says fund manager Kyle Bass.

Differentiating the Philippines from Argentina

As I have tried to demonstrate here, the shared objectives of the government of Argentina and the Philippines have been one of access to credit. The basic difference has been the means of action to accomplish the desired ends. Argentina has been deprived of such access and thus has resorted to the printing press, while the Philippines has sold to the domestic and international audiences—a boom story—in order for the government to have easy access to credit. The central bank engineered credit boom combined with the government publicity ‘anti-corruption’ stunt paid off, the Philippines got three credit rating upgrades in 2013.

Yet in contrast to Argentina, the Philippine banking system has been responsible for the massive inflation through loan-deposit creation.

By adapting financial repression via negative real rates, such has produced invisible subsidies for government liabilities. The incumbent government has deftly shifted her debt profile from foreign denominated to predominantly local currency denominated to benefit from such transfers.

Importantly, via credit inflation, corporate earnings have been inflated. This produced inflated tax collections which has sustained extravagant growth in government fiscal budget.

In short, the Philippine boom story has been pillared in credit inflation, thus the preposterous eight month 30++% M3 growth which if sustained ushers in the amplified risks not only of a bubble bust but worst—a currency crisis.

Although I believe the risks of a currency crisis may seem remote for now, all these depend on the BSP and the government’s actions.

Again monetary (credit) inflation affects prices in the economy and markets. Importantly monetary inflation will extrapolate to increases in interest rates. Even the US is beginning to show signs of this.

Because it is the banking system that has been doing the inflating in the Philippines by amassing boatloads of debt, the resultant price inflation will bring about rising rates that will increase the cost of servicing debt as well as curb demand.

The falling peso will also affect inflation and subsequently interest rates.

The government may resort to price management measures on the peso and on Philippine treasuries but for as long as these policies are maintained the King Canute effect will melt in the face of rudimentary economic laws.

Interest rates from both domestic inflation and falling peso will PRICK the bank credit bubble (the source of inflation). This is simply falls under basic law of economics.

Although I expect the Peso to fall substantially from current levels, it won’t likely collapse. But if the government will undertake massive measures to bailout favored interest groups that would be a far different story.

The Philippine government has been showing signs of embracing Argentina like policies. The sustained onslaught against the informal economy by supposedly widening tax base to include lechon dealers, mounting a public shame campaign and harassment on doctors and others, intrusions on household affairs, currency controls as the ban on coin savings/collections, the cybercrime law[24] which represents slippery slope towards censorship of the net (eventual censorship on inflation reporting?) and others—are symptoms of economic repression. Combine economic repression with financial repression—the latter signifying a transfer to the government and to cronies—these are hardly signs of real economic growth but politically manipulated economic activities.

The refusal to curtail the credit boom exposes on the chronic addiction by the Philippine government on easy money stimulus. Yet the government has been boxed into a corner. Tighten money supply, credit shrinks and so will the economic sectors who breathes in the oxygen of credit that has played a vital role in the sprucing up of the pantomime of the pseudo economic growth boom.

Tolerate more negative real rates, debt accumulation intensifies, price inflation will rise, the peso will fall and such credit inflation will be reflected on interest rates, where the outcome will be market based tightening regardless of the actions of authorities.

And eight successive months of 30++% M3 growth is a clear and present danger signal that exhibits the forces that underpins the Black Swan[25] has been progressing fast.

Bottom line: the fundamental difference between Argentina and the Philippines: Argentina has been conspicuously a government bubble headed for a collapse. The Philippines has been a bank credit bubble which the government has been using as cover to conceal her own bubbles. Yet the days of the Philippine banking credit bubble have clearly been numbered. And this has been ensured by eight consecutive months of an incredulous M3 growth rate at 30++%.

What A Replay of the 2013 Mania Means

Just recently I raised the issue of the uncanny resemblance between boom days of 2013 and today via a creeping Déjà vu of the February 2013 Mania[26], where I noted of three similarities: (one) parabolic-ballistic move by the Phisix, (two) similar “marking the close” on the trading session of February 28th for both years, and (three), the short correction cycle, began in March 11, 2013 as against March 12, 2014.

As against 2013 where a 6% correction took place, the current correction phase turned out to be only half, but the correction phase today has been a little longer

I further pointed out that the reason for the similarity has been due to current participants attempting to resurrect the boom which sailed with the tailwinds of easy money, as against the current conditions, where the boom has been running against strong headwinds of the M3 at 30++% (!) and a falling peso.

So far the 2013 and 2014 mania has amazingly rhymed. Yet if the 2013 cycle will play out in the entirety, then sad to say that this boom will abruptly end in June.

Celestially Valued Issues Are Soon Earth Bound

I have demonstrated how market participants have embraced delusions of grandeur by frenetically bidding up of the outrageously overpriced Philippine stocks based on Price Earning Ratios (PER)[27]

I now present to you the price to book value of the 30 member companies of the Phisix.

The price to book value is simply the stock market value relative to the book value[28]—cost of an asset net of depreciation, net asset value of a company net of liabilities goodwill and patents or initial outlay for investment net of gross expenses[29].

Based on Friday’s close and based on 2013 book values, the numbers have simply been astoundingly outlandish. One third of the Phisix components have PBV of over 4 (yellow). Also only one third of the same companies have seen their compounded annual growth for the past four years at over 10% (green). Many of the 10+% 4 year growth have been products of the 2013 expansion driven by the BSP’s 30+% M3. Yet not all of the high growth in asset values has high PBVs.

What does investopedia.com[30] say about high PBVs?

A company with a very high share price relative to its asset value, on the other hand, is likely to be one that has been earning a very high return on its assets. Any additional good news may already be accounted for in the price.

In short, whatever anticipated good news has already been priced in. Yet speculators haven’t had enough of these acutely expensive, overvalued and immensely mispriced securities.

Proof?

Based on Friday’s close and the highest and lowest PE ratio, we see the Phisix returning 11.4% year to date because many continue to panic-buy into astronomical PE stocks. Why panic buying? Are these people simply afraid to miss out?

But the lowest PE stocks have lent some support on the Phisix with 3 out of the 5 outperforming the Phisix. This means that growth expectations has been seen by the consensus as a one way trade or one way street. There is no room or margin for error.

Remember PE ratios are historical data. Once the impact of the 30% M3 growth will be felt in the real economy, conditions will dramatically change to impact negatively Earning Per Share (EPS) and Book Values (BV), thus rendering current prices at even a pricier state.

In my view these reckless yield chasing have been representative of the central banking PUT on the stock markets.

And if the consensus believes that Philippine stocks have been ‘dirt cheap’ compared with galaxy valued US technology stocks as previously shown here, the current meltdown in the same popular technology stocks that has brought them to bear markets is sign of a return to reality or normalcy.

LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook and Netflix have all entered their respective bear markets.

And so as with Yelp, Yandex, Tencent holdings, Groupon, Service Now, Salesforce.com and Netsuite.

Pretty soon illusions will be unmasked.

Take it from John Maynard Keynes who as quoted in the heading has admitted that he failed to see the Great Depression coming because of blind spots and selective perception.

[1] See Phisix: The Myth of the Consumer ‘Dream’ Economy July 22, 2013

[2] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Inflation Decelerates Further to 3.9 Percent in March April 4, 2014

[3] See Phisix: BSP’s Response to Peso Meltdown: Raise Banking Reserve Requirements March 31, 2014

[4] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Domestic Liquidity Growth Remains Strong in February March 31, 2014

[5] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Depository Corporations Survey January 2014

[6] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Bank Lending Expands Further in February March 31, 2014

[7] See Phisix: Global Financial Volatility Intensifies February 10, 2014

[8] See Phisix: Have You Been Aware of This Week’s Peso Meltdown? March 24, 2014

[9] Investopedia.com Price Inflation

[10] Ludwig von Mises 13. Prices and Income XVI. PRICES Human Action Mises.org

[11] Hayek, Friedrich A. The Use of Knowledge in Society Library of Economics and Liberty

[12] Wall Street Journal Argentine Central Banker Says He Aims to Slow Money Growth December 24, 2013

[13] Wikipedia.org Argentine debt restructuring

[14] Wikipedia.org Argentine debt restructuring

[15] Wikipedia.org Argentina Nationalization

[16] New York Times Argentina Nationalizes $30 Billion in Private Pensions October 21, 2008

[17] See Argentina’s Road to Serfdom: Book Import Bans March 31, 2012

[19] Bloomberg.com Argentina to Ease Currency Controls After Devaluation January 25, 2014

[20] Wall Street Journal Argentina Plans Measures Against Businesses Raising Prices March 1, 2014

[21] See Argentina Government Threatens Jail Terms for People who Question Inflation Data September 15, 2013

[22] Merco Press Printing money does not lead to inflation, argues Argentine central bank president March 26, 2012

[23] Professor Steve H. Hanke: The Troubled Currencies Project Cato Institute

[24] Wikipedia.org Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012

[25] See Phisix: Will a Black Swan Event Occur in 2014? January 13, 2014

[26] see Phisix: A Deeper Look at the Philippine and Indonesian Stock Market Mania March 17, 2014

[27] see Phisix: The Stock Market Mania Deepens March 10, 2014

[28] Investopedia.com Price-To-Book Ratio - P/B Ratio

[29] Investopedia.com Book Value

[30] Investopedia.com Using The Price-To-Book Ratio To Evaluate Companies February 23, 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment