At the outset, the masses misinterpreted it as nothing more than a scandalous rise in prices. Only later, under the name of inflation, the process was correctly comprehended as the downfall of money—Konrad Heiden

The Philippine Food Services Sector: How They Have Coped with the Impact of the Raging Inflation

Price instability affected the Philippine Food Services sector unequally, with SMEs likely taking the brunt. Although the industry survived, it faces critical challenges ahead.

Businessworld, May 18, 2023 (bold mine): Successful restaurants are always looking for creative ways to protect the bottom line without giving the impression that quality is going down with it. “Without dropping names, restaurants with multiple franchises in premium locations whether malls or high-traffic areas seem to be cutting costs in creative ways,” Mr. Alcantara said in a Facebook Messenger chat. Some keep their prices but use smaller utensils to serve food, while others use a wide array of chemicals such as food coloring or enhancers to save on raw ingredients but present the same food customers have known, he added. …As price volatility continues, food and beverage establishments continue to adjust to changing prices to make money while serving their customers well.

Anecdotes of food entrepreneurs trying to survive price instability are helpful signs of sentiment and possibly real-life experiences.

But articles can only limn a part of reality.

And mainstream reports usually fall for the survivorship bias—covering the success stories while ignoring the rest.

I. Margin Squeeze: Higher Food CPI than Resto CPI

The aforementioned anxieties have also been expressed through the prism of the official food CPI relative to the food services (& accommodation) CPI.

Figure 1

With input (food) prices rising faster, coping with a margin squeeze could signify an existential challenge for SME entrepreneurs.

What's more. The negative spread between the food CPI and food services CPI emerged sporadically since 2020. But it became dominant in 2022. The variance has turned positive only in Q1 2023. (Figure 1, upper chart)

Based on pure numbers, the profit margin squeeze would have caused a significant shutdown of retail outlets in the industry.

But, of course, this scenario hasn't occurred.

Instead, as an adjunct to accommodation, the food services sector, had one of the fastest GDPs in Q1 2023, which clocked in growth rates of 27.6% "current" and 17.5% "real."

And the blazing growth rate began in Q2 2021. That's when the pandemic policies eased, and the public was gradually allowed out of their home "gulag."

The growth rates of the aggregate sales of the top 4 listed food retail outlets, namely Jollibee, McDonald's, Shakeys, and Maxs, resonated with their sector's GDP. Total revenues soared by 31.6% in Q1 2023—faster than the nominal GDP. (Figure 1, lower chart)

As a side note, of the four retail chains, JFC commanded a 77% share in revenues and a 76% share in net income as of Q1 2023. And so, unless averaged, nominal figures are entirely dominated by JFC.

II. Thanks to the Boom in Consumer Credit, Listed Top Food Retail Chains Grew Profit Margins Until Q1 2023

Figure 2

Even more, price instability hardly affected the profit margins of the food chain titans, which expanded through Q2 or Q3 of 2022, although the margins of three of the four chains decreased in Q1 of 2023. (Figure 2)

However, JFC’s margins steadied at 17-18% in the last five quarters.

With Q1 CPI at 8.3%, the average margins of the four retail food chains slipped to 21.6%, the lowest since Q3 2021—indicating inflation’s impact.

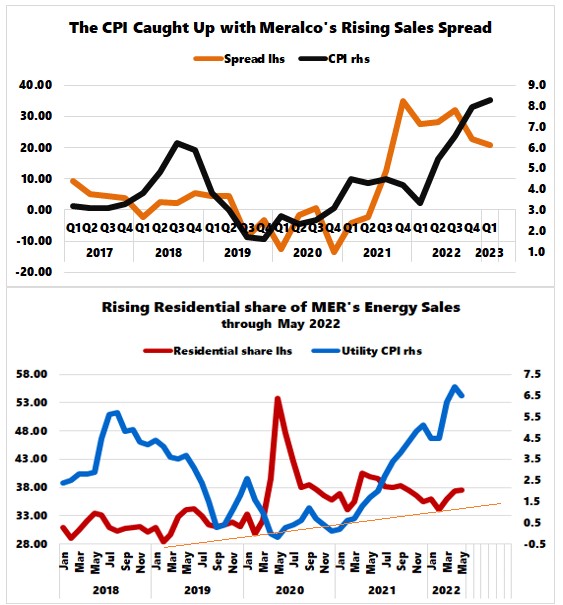

Figure 3

Thanks to the torrid growth of consumer credit, particularly credit cards, not only were the retail chains able to pass through the increases in their input prices to consumers that generated record sales, but these price hikes also protected their margins.

Net income growth peaked in Q2 2022 for the big four retail chains but plunged afterward. Because of JFC's 3.2% contraction, the group's total income posted a modest 7.8% growth in Q1 2023—better than the 71.4% shrinkage in Q4, mainly due to the 99% plunge of JFC. (Figure 3, top and middle diagrams)

Though income in peso bounced from Q4 2022, it was 31% below the Q4 2021 acme. (Figure 3, lowest chart)

III. Financing Cost Compounded the Erosion in Net Income

Figure 4

The fall in income wasn't only due to the diminished margins. Higher financial expenses from the recent rate hikes and elevated debt levels contributed to income erosion. (Figure 4, top and bottom charts)

Alliance Global didn't specify the debt levels of its subsidiary, McDonald's, so the chart exhibits the total debt levels of JFC, Shakey's, and Max's.

The takeaway is that the biggest retail food chains were least affected by price instability.

Instead, SME food enterprises bore the brunt of inflation.

But for the food retail chain titans, it was more than inflation; a corrosive influence on their bottom line was debt.

IV. The Distinctive Impact and Subjective Response to Inflation; Why Price Instability Challenges Remain

In any event, there is no one-size-fits-all on the impact of a high inflation regime on this sector. It depends on many factors, such as products, production and organizational structure, technology, suppliers, logistics, management, labor, and other internal processes.

Most critically, retailers are dependent on the distinctive character of their markets.

And we may never know how much "cutting corners" to save on costs had been employed by either the giants or the SMEs.

Perhaps, "carinderias," or small eateries, have been the most susceptible to a margin squeeze as raising prices leaves them extremely vulnerable to competitors. So, they could be more vulnerable to "cutting corners."

And as previously noted, in dealing with inflation, companies or enterprises may resort to reducing quantities offered (shrinkflation), lowering the quality of products (value deflation), or implementing charges or fees on auxiliary goods or services, such as paying for additional gravy and other previously freebies (sneakflation).

Statistics do not incorporate such maneuverings. But it happens anyway as shown by the anecdote from the referred article.

The thing is, the waves of price instability may not be going away anytime soon.

Though the current decline in headline inflation represents the 2nd phase of the 3-wave cycle, the structural forces of inflation remain intact—bank credit expansion and credit-financed fiscal deficits. Dislocations in supply chains only worsen it.

Moreover, price pressures represent expenditures from increased monetary surpluses (bank credit and central bank liquidity expansion). Because price increases siphon these excesses, feeding "demand" requires more monetary surpluses, which authorities are now attempting to squelch.

And that represents only one part of instability.

The next thing is, if credit expansion slows or even stops, it would likely cause disorderly adjustments for entrepreneurs who adapted their business operations to the current high inflation regime.

Food entrepreneurs should instead focus on their markets or how their customers could respond to sharp price oscillations from credit flows and make the necessary adjustments.

As showcased above, even from the perspective of the market leaders, the conspicuous topline gains have barely filtered into the bottom line.

What happens when revenue growth or the nominal GDP falters? And how should this impact the SMEs?

And what happens when the third wave arrives?

My humble guess is that most will be unprepared for an era of inflation.