Investing Against Popular Wisdom

In the world of investing, the wisdom of the crowds, especially during inflection periods, represents as a potential hazard to one’s portfolio. This is where the Wall Street axiom applies, “bulls make money, bears make money, but pigs get slaughtered”.

This happens for the simple reason that abdicating independent reasoning or analysis for groupthink increases the risks of overconfidence, which tends to influence people’s decision making by underestimating risks while simultaneously overestimating rewards.

Moreover, as I wrote on crowd thinking[1],

Groupthink fallacy is the surrender of one’s opinion for the collective. This accounts for as a loss of critical thinking and is reflective of emotional impulses in the decision making of the crowd. When groupthink becomes the dominant mindset of the crowd, an ensuing volatile episode can be expected to occur applied to both markets and politics (bubble implosion or political upheaval).

Veteran, battle hardened and successful investing gurus have all recommended to avoid populism. For them the herding effect signifies unsustainable crowded trades and or that the most profitable opportunities lie within themes that have hardly been seen by the crowds.

For instance, the billionaire George Soros via his reflexivity theory[2] wrote that we should be alert to the crucial psychological features of boom bust sequence; particularly

-The unrecognized trend,-The beginning of the self-reinforcing process-The successful test-The growing conviction, resulting in the widening divergence between reality and expectations-The flaw in perceptions-The climax and-The self-reinforcing process in the opposite direction

The point is that during the pinnacle or the troughs of booms and bubble bust episodes, people’s perception of reality become greatly distorted by biases.

One of the distinguished mutual fund investor John Neff similarly advised that[3]

It's not always easy to do what's not popular, but that's where you make your money.

Warren Buffett also said

Most people get interested in stocks when everyone else is. The time to get interested is when no one else is. You can't buy what is popular and do well.

The bottom line is that when everyone thinks the same then no one is thinking. And when we do not think, we lose money.

The Myth of the Consumption Economy

When everyone thinks that today’s boom is sustainable, since the public has been made to believe that current market dynamics have been founded on sound social policies and genuine economic growth, then this for me represents Mr. Soros’ “the growing conviction, resulting in the widening divergence between reality and expectations and the flaw in perceptions” which eventually leads to the “climax”.

And part of today’s Philippine boom has been predicated on supposedly a ‘consumption economy’, where the popular narrative holds that consumption, which has been portrayed as an independent force from producers, drives the economic prosperity.

In reality, every producer is a consumer. The world is interconnected such that production and consumption represent as people’s activities for survival and for progress. But not every consumer is a producer. The government is an example.

As the great Austrian economist Professor Ludwig von Mises wrote[4],

Economics does not allow of any breaking up into special branches. It invariably deals with the interconnectedness of all the phenomena of action. The catallactic problems cannot become visible if one deals with each branch of production separately. It is impossible to study labor and wages without studying implicitly commodity prices, interest rates, profit and loss, money and credit, and all the other major problems. The real problems of the determination of wage rates cannot even be touched in a course on labor. There are no such things as "economics of labor" or "economics of agriculture." There is only one coherent body of economics.

The reason people work is to earn (or implied production) in order to consume. In today’s modern economy one’s earnings, as expressed by money, indirectly represents real savings from our production or services provided.

Yet simple logic holds that if everyone consumes and no one produces then there will be nothing to consume. Thus we can only consume what we produce. In short, real prosperity arises from the acquisition of real savings or capital accumulation from production.

As the great French economist Jean Baptiste Say wrote[5], (italics original)That which is called productive capital, or, simply, capital, consists of all those values, or, if you will, all those advances employed reproductively, and replaced in proportion as they are destroyed.It is easy to see that this term capital has no relation to the nature or form of the values of which capital is composed (their nature and form vary perpetually); but refers to the use, to the reproductive consumption of these values: thus a bushel of corn forms no part of my capital if I employ it to make cakes to treat my friends, but it does form part of my capital if I use it in maintaining workmen who are employed on the production of that which will repay me its value. In the same manner a sum of money is no longer a part of my capital if I exchange it for products which I consume: but it does form part of my capital if I exchange it for a value which is to remain and augment in my hands…Capital is augmented by all that is withdrawn from unproductive consumption, and added to aconsumption which is reproductive.

Importantly consumption does not increase wealth, instead unproductive consumption destroys wealth

Again Jean Baptiste Say[6],

It must be remembered that to consume is not to destroy the matter of a product: we can no more destroy the matter than we can create it. To consume is to destroy its value by destroying its utility; by destroying the quality which had been given to it, of being useful to, or of satisfying the wants of man. Then the quality for which it had been demanded was destroyed. The demand having ceased, the value, which exists always in proportion to the demand, ceases also. The thing thus consumed, that is, whose value is destroyed, though the material is not, no longer forms any portion of wealth.A product may be consumed rapidly, as food, or slowly, as a house; it may be consumed in part, as a coat, which, having been worn for some months, still retains a certain value. In whatever manner the consumption takes place, the effect is the same: it is a destruction of value; and as value makes riches, consumption is a destruction of wealth.

So to argue that consumption leads to wealth is like pulling a wool over one’s eyes.

But of course the principal reason behind the populist consumption economy narrative has been to justify myriad government interventions via ‘demand management’ measures applied against the supposed insufficient “aggregate demand” from so-called “market failures”.

Moreover, the consumption story aims to buttress mostly indiscriminate debt

acquisition as a means of attaining statistical rather than real growth based on value creation.

Since politics is mainly short term oriented, thus populist short term policies via inflationism and via assorted interventions only distorts and obstructs the economy from its natural path. Instead, the typical ramification has been wealth consumption, part of it as consequence from boom bust cycles.

The implicit design behind the debt consumption policies has been to support the politically privileged banking system, whom provides financing to the redistributionist government through bond purchases, and the government and the political class, who not only profits from continued forcible extraction of resources from the private sector but likewise resort to debt generation to fund pet projects to ensure their hold on power.

Central banks, essentially, act as guarantor and as lender of last resort to both government and the banking system.

The same fiction of the consumption economy has been used to rationalize not only credit financed domestic property bubble[7] but also a shopping mall bubble.

By the way property and shopping mall are of the same lineage.

Will Remittances Sustain the Consumption Story?

Last week in dealing with the shopping mall bubble I concentrated on the supply side of the industry[8].

For this week, my focus will be on the consumption side.

As previously explained, there are three ways to finance consumption, through productivity growth, through consuming of savings or through contracting of debt.

On the productivity side, one of the popular mainstream meme is that remittances from Overseas Foreign Worker (OFW) have been responsible for most of the economic growth expressed via the consumption economy.

For most news accounts, consumption has been strongly associated with remittances, or said differently, remittances drives Philippine consumption.

According to the BSP[9], remittances in November of 2012 grew by 7.6% over the same period, totalling $21.6 billion for 11 months or 6.1% from last year.

The Philippine economy according to World Bank Development indicator in 2011, as cited by the Wikipedia.org[10], was at nominal $224.8 billion, this effectively means remittances through November translates to about 10% of the economy.

Only in media do we see 10% as mathematically greater than 90%. Even if we assume that all money sent by overseas workers are spent on consumption and or partially on investments (sari sari stores and etc…), there is little to show that the supposed multiplier effect of remittances will lead to 50% of current consumption levels.

Yet of course, I would posit that some of the remittances could have partially been “saved” in the banking system and perhaps even through the non-bank system. This is what media and their experts consistently ignore.

While the BSP did not provide the average growth, Yahoo Singapore[11] quotes one of the Singaporean financial institution, the DBS Bank as estimating the monthly average growth based on October data, at 5.8%.

Granting that media and their experts have been indeed correct in saying that remittances serves as the core force for consumption, then unfortunately 5.8% would hardly cover the gap with the supply side’s or shopping mall operator or developer’s baseline growth of 10%.

One may add that there hardly has been a nominal or real sustained 10% growth based on Peso or US dollars since 2009 based on World Bank’s chart[12].

And given that remittances is essentially latched to the productivity growth of the global economy, which means that wages of OFW workers and OFW deployment depends on the domestic economies the OFWs are employed at, the prospects of lower economic growth would hardly transform into magic for remittances.

Note that the global remittance growth trend[13] has essentially tracked the remittance growth trend of the Philippines and the World GDP’s past growth[14].

Even if we add up the estimated 30-40% of remittance channelled through the informal economy, which is according to the Asian Bankers Association[15], where the real remittance level balloons to $31 billion (to include both formal and informal avenues), this will account for only 14% of the GDP. Remember informal remittances have not been a onetime event but a longstanding factor.

And if the consensus is right that global economic growth will remain sluggish, then remittances will hardly fill the void unless the growth in the informal remittances will intensely surprise to the upside.

So even if there should be a change in preferences in consumption and savings patterns by OFWs to favor more remittances (or transfers), the consumption story funded by mainly remittances will remain inadequate.

How about BPOs?

Another less popular but more potent consumption story is the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO)

The BPO industry has reportedly generated foreign exchange revenues of about $11 billion in 2011[16] and the industry’s growth has been expected to earn more than double to $25 billion in 2016. This translates to a Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 17.85%. If true, then BPO will surpass remittances in no time. But I believe that such projections seem wildly optimistic.

The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) also estimates the industry’s growth at 15%[17]

Depending on the analyst, estimates of growth for the BPO industry have had wide divergences.

The Philippine BPO association along with the Philippine government says they expect a 15% compounded annual growth rate for the global BPO market[18] (right window). Whereas Slovakia’s Soften-Accenture quoting the estimates of technology research giant Gartner[19] says that BPO and IT CAGR to grow 6.3% and 5.9% respectively. Research firm AT Kearney seems to conform to the Gartner estimates[20].

I believe that the fundamental reason for such patent disparity is that the association of the local BPO industry along with the government simply reads past performance into the future.

Nevertheless, where I believe they gone astray is that they have ignored the S-Curve cycle of the technology industry

The S-Curve as defined by Wikipedia.org[21]

The s-curve maps growth of revenue or productivity against time. In the early stage of a particular innovation, growth is relatively slow as the new product establishes itself. At some point customers begin to demand and the product growth increases more rapidly. New incremental innovations or changes to the product allow growth to continue. Towards the end of its life cycle growth slows and may even begin to decline. In the later stages, no amount of new investment in that product will yield a normal rate of return

In short, unless there will be assimilation of more productivity through newer innovation, the industry’s growth diffusion levels, as it ages, is bound to slowdown. I have used this curve to rightly predict the slowdown in telecom penetration levels.

Further, the Philippine competitive advantage has not been etched on the stone. While Philippine adaptation of the American English language has represented as the main competitive edge for her to supplant India on BPOs as global leader[22], but not in the ITOs, labor costs could be a factor.

In addition, the outsourcing industry is highly competitive, highly sensitive to technological changes and is likewise anchored to global growth. So while we might see more businesses adapt to the digital environment, it isn’t clear that BPOs can deliver the consumption story to cover the deficiencies from the formal economy and from the remittances.

So while I am highly optimistic on the technology industry, I have great reservations on industry estimates, which I hope will prove me wrong.

Will the Informal Economy Surprise?

This leads me to the informal economy.

Informal economy, for me, covers all the sectors that elude the government, whether they are the small scale vendors, manufacturers, service industry or smugglers and also those in formal industries that resort to tax avoidances.

Money excluded from forced redistribution can mean savings, investment and or consumption.

So far the statistical measures of the informal economy has been through labor which accounts for about 50% of the Philippine work force.

Agriculture is said to constitute the largest informal sector estimated at 64% according to a study[23] by the National Statistical Coordination Board. While I believe that statistics have most likely downplayed the important role played by agriculture, I believe much of the consumption story may have been from this sector which has partly piggybacked on the global commodity bullmarket. I say partly, because the sector has been tightly regulated and this applies not only to the Philippines but abroad too[24]

And given that the different estimates of banking penetration level, nonetheless all of them reveals of the lack of access by the average Filipinos to financial institutions, I believe that government statistics may not have captured the off banking savings rate which may have contributed to the consumption story.

The US Agency for International Development[25] suggests that only 26.56 percent of Filipinos aged 15 years old and above have accounts with banks or financial entities whereas the McKinsey Quarterly[26] estimates that only 35% of Filipinos has bank accounts or accounts with a financial institution.

In other words while I believe that there has been more savings for the consumption story, I think that productivity growth even in the informal economy may not sustain the supply side growth of the shopping malls.

So unless the government will dramatically liberalize the agricultural sector given its tightly controlled conditions, there is unlikely the possibility for a fill in the gap role for the informal sector considering the steep projected growth in the shopping mall supply.

The other way is for the bulls to hope that all statistics are wrong.

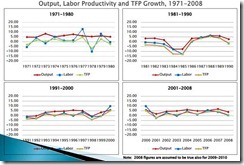

Finally the Philippine productivity growth story over 4 decades has hardly shown the stuff required to support the consumption story. Growth of over 10% has been an outlier.

The good news is that the author of the study makes the case for the openness of the economy[27] as one of the pillars to improve on productivity, something which today’s government does not see as a priority.

I will end this rather lengthy report with an update[28] from the Bangko ng Pilipinas on domestic banking credit conditions, which again reported a strong credit growth in November (14%) but has been modestly down from October (15.8%) [bold mine]

Loans for production activities—which comprised more than four-fifths of banks’ aggregate loan portfolio—grew by 14.6 percent in November from 16.4 percent in the previous month. Similarly, the growth of consumer loans eased to 12.1 percent from 13.9 percent in October, reflecting the slowdown across all types of household loans.The expansion in production loans was driven primarily by increased lending to the following sectors: real estate, renting, and business services (24.8 percent); wholesale and retail trade (by 26.9 percent); financial intermediation (37.3 percent); manufacturing (13.6 percent); transportation, storage, and communication (26.5 percent); and public administration and defense (48.9 percent). Meanwhile, declines were observed in lending to mining and quarrying (-39.5 percent) and agriculture, hunting, and forestry (-41.8 percent).

The growth rate reported by the BSP on the banking sector’s credit growth for real estate and retail trade seems consistent with the baseline of 10% supply side growth for the shopping malls. Shopping malls are essentially real estate business, while the retail segment are the lessees of the malls (aside from ex-mall outlets). So developers and retail operators continue to see double digit consumer growth for them to indulge in a massive buildup of debt.

Yet if the loans by the real estate and retail trade sectors grow by 20% per year as baseline, then their exposures with the banking sector effectively doubles in the fourth year. Of course this view excludes the past loans that have already been incurred.

The bottom line is that while there are many imponderables which this analysis may not secure, the seeming amplification of the asymmetric growth between demand and the supply malls may lead to serious economic imbalances which eventually will be reflected on the markets through a tumultuous backlash. Entrepreneurial errors, mostly fed by social (central banking) policies via distorted prices, and from popular but flawed theories, have only worsened the situation. The fingerprints of the (Austrian) business cycle seem everywhere.

As a final note, bubble cycles are market processes influenced by social policies and are shaped over time. The persistence of the trend will be conditional to the forces that have triggered them. If the current supply side trend persists without accompanying material real growth in productivity (i.e. not based on credit and from government expenditures) and if both sides will continue to accrue more debt in response to the present suppression of the interest rate environment, then the risks of a bubble bust will loom larger as time goes by. The other factor will be how authorities respond to changing conditions.

[1] See The UNwisdom Of The Crowd August 15, 2010

[2] George Soros The Alchemy of Finance p.58

[3] Businessinsider.com 22 Insights From The Most Successful Investors In History, January 15,

[4] Ludwig von Mises, XXXVIII. THE PLACE OF ECONOMICS IN LEARNING 4. Economics and the Universities Human Action Mises.org

[5] Jean Baptiste Say Catechism of Political Economy Mises.org

[6] Ibid

[7] See Philippine Overseas Workers Help Fuel Philippine Property Bubble, June 14, 2012

[8] See Philippine Economy’s Achilles Heels: Shopping Mall Bubble (Redux) January 13, 2013

[9] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Remittances Sustain Growth in November 2012, January 15, 2013

[10] Wikipedia.org Economy of the Philippines

[11] Yahoo Singapore Philippines' remittances from overseas workers spike by 8.5%, January 15, 2013

[13] World Bank Outlook for Remittance Flows 2012-14 Migration and Development unit December 1, 2011

[14] The Economist World GDP Graphic detail January 15, 2013

[15] Businessmirror.com ‘Informal’ OFW remittances P242 billion higher, November 14, 2012

[16] Rappler.com BPO industry welcomes Obama win despite anti-outsourcing threat, November 10, 2012

[17] East Vantage.com 15% in Annual Growth in BPO Philippines Says NEDA

[20] Avaya Blog Statistics of the Global BPO Industry

[21] Wikipedia.org Diffusion Innovation

[22] New York Times A New Capital of Call Centers, November 25, 2011

[23] Jose Sibal Measuring the Informal Sector in the Philippines and the Trends in Asia National Statistical Coordination Board October 2007

[24] See Agricultural Boom Fuels Farmland Protectionism, May 28, 2011

[25] Inquirer.net Philippines lags behind peers in bank penetration, survey shows, May 3, 2012

[26] See The Rise of Mobile Banking, May 23, 2012

[27] Gilberto M. Llanto Philippine Productivity Dynamics in the last 5 decades Philippine Institute for Development Studies and factors influencing

[28] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Bank Lending Continues to Grow in November, January 17, 2013

1 comment:

You nearly hit the nail right on the head. Sadly, you hammered your thumb instead.

True, the tail cannot wag the dog. $21 billion in remittances (2012 est.) simply cannot influence the overall PCE number (approx. $175B, 2012 est.). Moreover, in Peso terms, remittances are up by only 2% or thereabouts.

Nevertheless, PCE in the first nine months is up more than 10% in nominal terms. If remittances did not contribute to PCE growth, and if household savings are up 6% according to the BSP, then the domestic economy must be very strong. BPOs, construction, tourism and even manufacturing (yes, manufacturing! Meralco's sales breakdown will show you that industrial customers led KwH sales growth last year) are the large, labor intensive sectors that are driving the country's growth.

You are certainly not the first to propound the idea of a shopping mall bubble. More than 10 years ago, some analysts were saying that the metropolis was already "overmalled". Obviously, they were dead wrong. Capacity in the NCR alone has grown by leaps and bounds since then and yet occupancy rates remain very high. In the most popular malls, there is still a waiting list for potential lessees.

You will be, or already are, dead wrong too.

Post a Comment