Life is not about self-satisfaction but the satisfaction of a sense of duty. It is all or nothing. Nassim Nicholas Taleb

The Bernanke Put: If we were to tighten policy, the economy would tank

I don't think the Fed can get interest rates up very much, because the economy is weak, inflation rates are low. If we were to tighten policy, the economy would tank.

That’s from Dr. Ben Bernanke, US Federal Reserve Chairman’s comment during this week’s Question and Answer session in the congressional House Financial Services Committee hearing[1].

This practically represents an admission of the entrenched addiction by the US and the world financial markets on the central bank’s sustained easy money policy. This has likewise partially been reflected on the US and global economies. I say “partially” because not every firms or enterprises use leverage or financial gearing from banks or capital markets as source of funding operations. Since I am not aware of the degree of actual leverage exposure of each sector, hence it would seem to use “safe” as fitting description to the aforementioned relationship.

The fundamental problem with easy money dynamics is that these have been based on the promotion of unsound or unsustainable debt financed asset speculation and debt financed consumption activities, in both by the private and in the government, in the hope of the trickle down multiplier from the “wealth effect”.

The reality is that such policies does the opposite, it skews the incentives of economic activities towards those subsidized by the government particularly financial markets, banks, and the government (via treasury bills, notes and bonds as low interest rates enables sustained financing of the expansion of government spending) which widens the chasm of inequality between these politically subsidized sectors at the expense of the main street. For these sectors, FED’s easy money policies signify as privatization of profits and socialization of losses.

Yet the massive increases in debt as consequence from such loose interest rate policies, magnifies not only credit risk, thus affecting credit ratings or creditworthiness, but importantly the diversion of wealth from productive to capital consuming activities, which ultimately means heightened interest rate and market risks.

Eventually no matter how much money will be injected by central banks, if the pool of real savings will get overwhelmed by such imbalances, then interest rates will reflect on the intensifying scarcity of capital.

Capital cannot simply be conjured by central bank money printing, as the great Ludwig von Mises warned[2] (bold mine)

The inevitable eventual failure of any attempt at credit expansion is not caused by the international intertwinement of the lending business. It is the outcome of the fact that it is impossible to substitute fiat money and a bank's circulation credit for capital goods. Credit expansion can initially produce a boom. But such a boom is bound to end in a slump, in a depression. What brings about the recurrence of periods of economic crises is precisely the reiterated attempts of governments and banks supervised by them, to expand credit in order to make business good by cheap interest rates.

From such premise, interpreting “low” interest rates as a function of “weak” economy and “low” inflation seems relatively inaccurate.

Such assessment has been based on the rear view mirror. As of Friday, Oil (WTIC) at US $108 per bbl and gasoline at $ 3.12 per gallon, as noted last week[3] US producer prices have also been rising, which reflects on an inflationary boom stoked by credit expansion. If energy and commodity prices persist to rise, then “low” price inflation will transform into “high” price inflation. Thus “price” inflation, as corollary to monetary inflation, will likely add pressure on bond yields and interest rates.

Moreover record levels of US stock markets imply of intensifying asset inflation. Prior to the bond market turmoil, US housing has also caught fire. “Low” levels of price inflation or what mainstream sees as “stable prices” doesn’t imply of the dearth of accruing imbalances, on the contrary, these are signs of the boom bust cycle in motion channeled through specific industries, similar to the “roaring twenties[4]” or the US 1920s bubble and the 1980s stock and property bubble in Japan.

As the great dean of the Austrian school of economics, Murray N. Rothbard explained of the inflating bubble of 1920s amidst low price inflation[5]:

The trouble did not lie with particular credit on particular markets (such as stock or real estate); the boom in the stock and real-estate markets reflected Mises's trade cycle: a disproportionate boom in the prices of titles to capital goods, caused by the increase in money supply attendant upon bank credit expansion

The same bubbles on “titles to capital goods”, via stocks and real estate, plagues from developed economies to emerging markets, whether in Brazil, China or ASEAN.

And “weak” economy in the backdrop of elevated levels of interest rates powered by price inflation had been a feature of the stagflation days of 1970s.

Finally, while price inflation, scarcity of capital and deterioration of credit quality are factors that may lead to higher interest rates as expressed via rising bond yields, another ignored factor has been the relationship between the growth of money supply and interest rates.

As Austrian economist Dr. Frank Shostak explains[6]

an increase in the growth momentum of money supply sets in motion a temporary fall in interest rates, while a fall in the growth momentum of money supply sets in motion a temporary increase in interest rates.

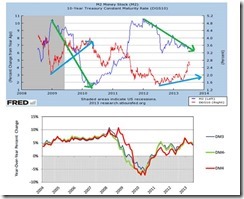

Such momentum based relationship can be seen in the Fed’s M2 and the yield 10 year constant maturity or even with the Divisia money supply

On the top pane, in 2008-2010, as the Fed’s M2 (percent) simple sum aggregate (blue line) collapsed, the yields (percent change from a year ago) of 10 year constant maturity notes soared. Following the inflection points of 2010, the relationship reversed, particularly the M2 soared as the Fed’s 10 year yields fell.

The M2 commenced its decline on the 1st quarter of 2012 while the UST 10 year yield rose in July or with a time lag of over three months.

The Divisia money supply, instead of a simple sum index used by central banks, is a component weighted index which has been based on the ease of, and opportunity costs of the convertibility or “moneyness” of the component assets into money (Hanke 2012)[7].

The Divisia money supply has been invented by invented by François Divisia, 1889-1964 and has now been made available via the Center for Financial Stability (CFS) in New York, through Prof. William A. Barnett[8]

As of June[9], the varying indices of the Divisia money supply based on year on year changes have all trended downwards since late 2012.

The slowdown in the growth of momentum of money supply have presently been reflected on the upside actions of yields of the bond markets.

The momentum of changes of money supply will largely be determined by the rate of change of credit conditions of the banking system.

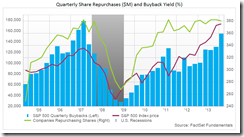

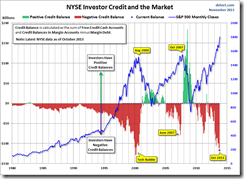

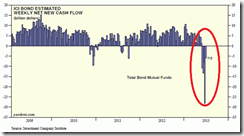

Rising bond yields largely attributed to the FED’s “tapering” chatter has spurred a huge $66 billion in the past 5 weeks through July exodus on bond market funds according to Dr. Ed Yardeni[10].

The destabilizing rate of change in bond flows appear as evidence of “If we were to tighten policy, the economy would tank”

Bernanke PUT’s Effect: Parallel Universes

The Q&A statement along with the Dr. Bernanke’s earlier comments in the House Financial Services Committee where he said central bank’s asset purchases “are by no means on a preset course[11]” has energized a Risk ON environment.

US stocks broke into record territories. Benchmarks of several key global stock markets rebounded. Global bond markets (yields) rallied along with commodity prices.

During the past two weeks, the financial markets have been guided higher by repeated assurances from Dr Bernanke aside from central bankers of other nations.

Given this cue, ASEAN stock and bond markets rallied substantially despite what seem as deteriorating fundamentals.

The sustained rout of the Indonesia’s rupiah appears to have been ignored by the stock and bond markets. Indonesia’s central bank, Bank Indonesia intervened in the currency market by injecting dollars into the system. Indonesia’s foreign exchange reserves dropped by $7.1 billion in June, the most since 2011, and which brings total reserves to less than $100 billion, a first in two years, according to a report from Bloomberg[12].

Indonesia’s unstable financial markets mainly via the bond and currency have prompted the World Bank to cut her growth forecast early June. Thailand’s central bank have downshifted their economic growth estimates along with their Ministry of Finance and the IMF[13].

The IMF has also marked down global economic growth due to “longer economic growth slowdown”[14], from China and other emerging economies whom have been faced with “new risks”

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has also trimmed growth forecast for ASEAN at 5.2% where the Philippines has been expected to grow 5.4% in 2013 and 5.7% 2014[15].

In contrast to the ADB, the IMF, whom downgraded world economic growth, has upgraded economic growth projection of the Philippines to 7% in 2013[16]

In the world of central bank inflationism, “fundamentals” in the conventional wisdom hardly drives the markets. Stock and bond markets may substantially rise even as the economy has been mired in a prolonged period of negative growth or recession. This has been in the case of France in 2012-13[17].

An investor in Chinese equities would have only earned 1% per year during the last 20 years even as per capita has zoomed by 1,074 percent over the same period, according to a Bloomberg report[18].

This shows how the discounting mechanism of financial markets has been rendered broken, relative to reality, reinforced by the stultifying effects of central bank easing policies.

And amidst sinking stock markets and the recent spike in short term interbank interest rates due to supposed cash squeeze from attempts by the Chinese government to ferret out and curtail the shadow banks, China’s increasingly unstable and teetering property bubble continues to sizzle with home prices rising in 69 out of 70 cities. Guangzhou, Beijing and Shanghai reported their biggest gains since the government changed its methodology for the data in January 2011 according to another report from the Bloomberg[19].

Such dynamics reinforces China’s parallel universe

Never mind that Chinese rating agencies downgraded “the most bond issuer rankings on record in June” as brokerage houses have been preparing for “the onshore market’s first default as the world’s second-biggest economy slows” according to another Bloomberg article[20].

China’s rampaging property bubble appears to be in a manic blow-off top phase

The Myth of the Consumer ‘Dream’ Economy

Speaking of mania, a further manifestation of the “permanently high plateau”, new order, new paradigm, “this time is different” can be seen from the president of the Government Service Insurance System Robert Vergara, who proclaims that the Philippines has reached a political economic nirvana.

From a Bloomberg report[21]:

The country “is still experiencing a secular growth story,” Vergara said. “We have the kind of economy that every country dreams of.”

Being an appointee of the Philippine president[22] it would seem natural to for him to indoctrinate or propagandize the public on the supposed merits of the current boom as part of the PR campaign for the government.

The GSIS president says he expects a return of 9% or more for the Philippine equity benchmark, the Phisix, over the next 12 months, as earnings will increase by about 15% during the next two years. All these have been premised on the ‘dream’ Philippine economy which he projects as expanding by 6-7% during the next 2 years and whose growth will be anchored by record-low interest rates which allegedly will fuel consumer spending.

What has been noteworthy in the reported commentary has been that of the GSIS’s president implied market support for local equities, where “the fund would consider increasing equity holdings to as much as 20 percent of total assets if the gauge falls below the 5,500 level”. If a private sector investor will say this they will likely be charged with insider trading.

And if he is wrong, much the retirement benefits of public servants risks being substantially diminished. Otherwise, taxpayers will be compelled to shoulder such imprudent actions.

But has the Philippine economy been driven by consumer spending as popularly held?

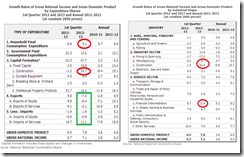

According to the National Statistical Coordination Board’s 1st quarter GDP report[23]:

With the country’s projected population reaching 96.8 million in the first quarter of 2013, per capita GDP grew by 6.1 percent while per capita GNI grew by 5.3 percent and per capita Household Final Consumption Expenditure (HFCE) grew by 3.4 percent. –

The same Philippine economic agency notes that based on the 1st quarter expenditure share of statistical economic growth, household final expenditure grew by only 5.1% (left pane). This has been less than the 7.8% overall growth rate of the economy.

Merchandise trade had hardly been a factor as exports posted negative growth while imports had been little changed. Government final expenditure grew by more than double the rate of household final expenditure or by 13.2%, and capital formation had been mostly powered by construction up by 33.7%.

From the industrial origin calculation perspective (right pane) we see the same picture. Construction soared by an astounding 32.5%. This has fuelled the Industry sector’s outperformance, which had been seconded by manufacturing 9.7%. Financial intermediation has also registered a strong 13.9% which undergirded the service sector. Public administration ranked fourth with 8% growth, about the rate of the nationwide economic growth.

So data from the NSCB reveals that during the 1st quarter, statistical growth has hardly been about the household consumption spending driven growth, but about the massive supply side expansion as seen through construction, financial intermediation, and secondly by government expenditures.

Yet here is what the Philippine ‘dream’ economy has been made up of.

Credit growth underpinning the fantastic expansion of the construction industry has been at a marvelous or breathtaking rate of 51.19% during the said period, this is according to the data from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas as I previously presented[24].

How sustainable do you think is such rate of growth?

Meanwhile, bank lending to financial intermediation and real estate, renting and business services and hotel and restaurants grew by a whopping 31.6%, 26.24% and 19.18%, respectively. Wholesale and retail trade grew by 12.49%.

Banking loans to these four ‘bubble’ sectors which embodies the shopping mall, vertical (office and residential) properties, and state sponsored casinos accounts for 53.25% of the share of total banking loans.

Remember household final demand grew by a relative measly 5.1% and this partly has been backed by bank lending too. Bank lending to the household sector grew a modest 11.89% backed by credit card and auto loans 10.62% and 13.86%. Only 4% of households have access to credit card according to the BSP.

The explosive growth in bank credit can be seen both in the supply and demand side. But the supply side’s growth has virtually eclipsed the demand side.

So based on the 1st quarter NSCB data the Philippine consumer story (provided we are referring to household consumers) has been a myth.

Basic economic logic tells us that if the supply side continues to grow by twice the rate of the demand side, then eventually there will be a massive oversupply. And if such oversupply has been financed by credit, then the result will not be nirvana but a catastrophe—a recession if not a crisis.

Given the relentless growth in credit exactly to the same sectors during the two months of April-May, statistical GDP growth will likely remain ‘solid’ and will likely fall in the expectations of the mainstream. The results are likely to be announced in August.

Prior to the Cyprus crisis of 2013, many Cypriots came to believe that this “time is different” from which many hardly saw the potential impact from a sudden explosion of public sector debt[25]

Unfortunately, a populist dream morphed into a terrifying nightmare.

BSP’s Wealth Effect: San Miguel as Virtual Hedge Fund

And for the moral side of the illusions of dream economy tale, given that only 21.5 of every 100 households have access to the banking sector, and as I previously explained[26], where domestic credit from the banking sector accounted for 51.54% of the GDP as of 2011, and also given that the wealthy elites control some 83% of the domestic stock market capitalization and where the residual distribution leaves 15-16% to foreigners while the rest to the retail participants, an asset boom prompted by BSP zero bound policy rates represents a transfer of wealth from the rest of society (most notably the informal sector) to the political class and their politically connected economic agents.

This should be a good example.

Publicly listed San Miguel Corporation [PSE: SMC] recently sold their shareholdings at Meralco for $399 million[27] to an undisclosed buyer.

The BSP inspired Philippine asset boom has transformed San Miguel from an international food and beverage company into a virtual hedge fund which profits from trading financial securities of the highly regulated sectors of energy, mining, airlines and infrastructure.

The 32.8% sale of Manila Electric or Meralco [PSE: MER] and the prospective 49% sale of another SMC asset, the SMC Global Power Holdings, reportedly the country’s largest electricity generator with assets accounting for a fifth of the nation’s capacity, has been expected to raise at least $1.6 billion[28], according to a report from Bloomberg

SMC sales of its Meralco holdings extrapolate to a huge windfall. According to the same report, SMC has tripled return on equity from its conversion to heavy industries.

Moreover, SMC has acquired about 40 companies for about $8 billion which has been partly funded by leverage where “the company and its units have 272 billion pesos worth of debt due by 2018 and San Miguel has 152 billion pesos in cash and near-cash items, the data show.”

Asked by a reporter about the prospects of the sale, the SMC’s President Mr. Ramon Ang bragged “Does San Miguel need the money? No. We can always borrow to fund any opportunity.”

Obviously, a reply based on easy money conditions.

As explained in 2009, the radical makeover of San Miguel has been tinged by politics[29]. The energy, mining, airlines and infrastructure which the company has shifted into are industries encumbered by politics mostly via anti-competition edicts. Thus asset trading of securities from these sectors would not only mean profiting from loose money policies, but also from also arbitraging economic concessions with incumbent political authorities.

The viability of these sectors particularly in the energy and infrastructure (roads) are endowed or determined by political grants. For instance in the case of Meralco, the Office of the President indirectly determines the “earnings” of the company via the price setting and regulatory oversight functions of the Energy Regulatory Commission which is under the Office of the President[30]. The private sector operator of Meralco has to be in good terms, or has blessing of, or has been an ally of the President. These are operations which can’t be established by analysing financial metrics for the simple reason that politics, and not, the markets determine the company’s feasibility.

San Miguel’s new business model allows political outsiders to get into these economic concessions through Mr. Ang’s political intermediations which it legitimately conducts via “asset trading”. SMC’s competitive moat, thus, has been in the political connections sphere.

SMC has also been a major beneficiary from the BSP’s wealth effect and wealth transfer from zero bound rates and from the Philippine government’s highly regulated or politicized industries.

Nonetheless leverage build up for asset trading necessitates a low interest rate environment. Should interest rates surge, and asset markets fall, Mr. Ang’s $35 billion dream might turn into an unfortunate Eike Batista[31] story.

Mr. Batista, the Brazilian oil, energy, mining and logistics magnate was worth $34 billion and had been the 8th richest man in the world a year ago.

Mr. Batista’s highly leveraged or indebted companies crashed to earth when commodity prices collapsed, and exposed such vulnerabilities. Debt deleveraging likewise uncovered the artificial wealth grandeur which has been embellished by debt.

Mr. Batista’s debt fiasco reduced his fortune to only $2 billion. At least he remains a billionaire.

Yet given his political connections, Mr. Ang may expect a bailout from his political patrons.

Risks remain high. Do trade with caution

[23] National Statistical Coordination Board, Highlights Philippine Economy posts 7.8 percent GDP growth May 30, 2013