``Financial success depends on the ability to anticipate prevailing expectations and not real world events.” -George Soros, Alchemy of Finance

When bad news comes, it pours.

China hasn’t been unscathed by the recent turn of events.

There have been increasing signs of impacts related to the contagion from the global financial crisis, even if its capital markets have been heavily regulated or its linkages to foreign markets or economies have been limited.

Reports like the “slowest industrial growth in seven years” (Bloomberg), “a sharp fall in manufacturing survey” by CLSA indicative of a prospective recession (Bloomberg), “the narrowing profit margins” and concerns over the “rising incidences of bad loans from overseas investment” (Bloomberg) or from declining financial markets, or decelerating export growth (Bloomberg) amidst a record trade surplus are just a few examples. Yet, despite the seemingly downcast message, the statistical figures still remain positive albeit ostensibly slowing.

Some strident perma bears have launched the offensive to downscale China’s economic growth forecast to 5-6% to reflect a hard landing, apparently to chime with their deflationary bias.

Figure 5: Economist: Breakdown of China’s GDP

Figure 5: Economist: Breakdown of China’s GDPFor starters, despite being popularly known for its export prowess, figure 5 from the Economist exhibits that net exports (exports-imports) account for about 3% of its GDP.

Arthur Kroeber at Dragonomics estimates that about 21% China’s manufacturing value is exported, while manufacturing accounts for only a third of GDP value and investment, of which only 7% of China’s investments are directly linked to export production.

Meanwhile the largest chunk of China’s GDP has been in investments which is estimated at 40% (the Economist) or 30% (Dragonomics-GaveKal) of the economy where over half of these are into infrastructure [30.8% of total construction investments (source: Dragonomics-Gavekal)] and property [24% of total construction investments].

Reflating China.

Faced with deteriorating signs of health in the global economy, despite a still vigorous export growth clip (emerging markets have offset declines in the US), emerging signs of strains in manufacturing, slumping stock markets and worst, declining real estate values as shown in Figure 6, aside the declining rate of investments in real estate (xinhua.net), instinctively, China’s recent response have been to launch a massive stimulus of $568 billion (Bloomberg) or equivalent to around 14% of its GDP in dollar terms (Economist).

Edmund Harriss of Guinness Atkinson lists latest policy measures undertaken by Chinese government prior to its massive $586 stimulus package namely, Tax rebates for exporters, Three interest rate cuts, Two cuts in the required reserve ratio, An injection of $4.4 billion into the banking system to ensure liquidity, An increase in bank lending quotas for smaller and medium-sized businesses, Lowering of the mandatory mortgage down-payment from 30% to 20%, Cut property transaction taxes and lowered mortgage rates, Municipal governments have launched a series of additional property supporting measures specific to their local markets.

In addition, the latest stimulus is said to cover (source Danske Bank):

-Construction of more affordable low-rent housing.

-Increasing investment in rural infrastructure (mainly road and power grids).

-Boosting investment in transportation (railway, airports and upgrade of urban power grids).

-Increase spending on healthcare and education.

-Improve environmental protection by investing in sewage, rubbish treatment and energy conservation.

-Extending reform in VAT reform to all industries (cut corporate taxation by CNY120bn).

-Income support by increasing agricultural subsidies and subsidies to low income urbane residents.

Some observations:

1) China’s bailout package reflects the general trend of global governments to concertedly ease monetary policies and use government coffers to pump prime the economy.

2) It is unclear how much of the total package represents new spending. Many of them were previously announced but have been currently incorporated probably aimed at gaining media or political mileage or having some impact on the financial markets.

3) It would appear that the main thrust of the stimulus would be to cushion the impact of the decline in investments which account for the biggest share in China’s GDP.

4) The spending measures will definitely benefit certain sectors or nations. But there will be lingering questions on the overall efficacy of such programmes or its possible unintended consequence.

5) Some have made comparisons to an almost similar policy stimulus program instituted during the Asian Crisis which managed to keep growth rates at nearly 8% in 1998-1999 (indexmundi.com). Although, China today is much bigger in size compared to the 90s, in as much as the extent of the external shock threatening China.

6) While the program is said be implemented within a two year window (Economist), such policy measures will take time before any material impact can be felt or assessed.

7) There is always the question of financing. It’s been said that the national government will account for 25% of the package, with unspecified amount to be shouldered by the local governments and the rest by so-called “social investments” (Northern Trust). The ambiguities from the sources of financing have led some to speculate on the risks that China could sell US treasuries at a time when the US is in dire need of funding for its fiscal programs. And selling US assets (mostly treasuries or agencies) could be detrimental to the already sensitive and volatile markets.

This doesn’t seem likely though. China has a national savings rate of 51.2% last year (San Francisco Chronicle) which could be channeled instead to fund such government expenditures than propping up of losing private investments in the property sector (as the US has done). Besides, roiling the already volatile markets could have undesired effects financially, economically or even politically.

Anticipating Prevailing Expectations: Shanghai Composite At Bottom?

How does this affect China’s markets or of Asia?

Well China has thrown various tools as mentioned above even prior to the latest stimulus program. It didn’t stop the major benchmarks from the hemorrhage. But this doesn’t mean the past will be the same.

Our idea is to look at history first.

Figure 7 chartrus.com: 17 year chart of China’s Shanghai Composite

Figure 7 chartrus.com: 17 year chart of China’s Shanghai CompositeChina’s1993-1995 bear market manifested a peak to trough loss of 73%, while the 2001-2005 version lost some 56%.

Of course the conditions of those years are starkly different than from today. Although from the standpoint of bear market losses- from which the Shanghai index peaked from October of 2007 (6,036.28) to its recent November lows (1719.77)- have registered a loss of nearly 72%, almost at the same depth as the bear market trough of the 90s.

In my view, this means that the market (barring a great depression) is likely near or at the bottom with or without the stimulus.

Although the stimulus could possibly work as a psychological booster. See figure 8.

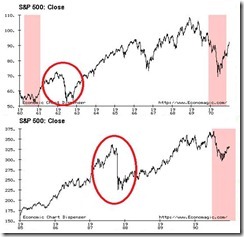

Figure 8: stockcharts.com: US markets-China/Japan/Asian Markets Diverging?

Figure 8: stockcharts.com: US markets-China/Japan/Asian Markets Diverging?This has been the same dynamics going on in the US markets. Many have been hoping for government actions to successfully prop up its domestic market, but to no avail.

Last week the US benchmarks attempted to test the October 10 lows and fleetingly passed. But maybe we might see a repeat of the test next week as the recent gains haven’t been successfully safeguarded.

Once again this takes us to the edge of our seats as to whether the US markets makes a pivotal decision point of either establishing a bottom or a new low.

However, as figure 8 shows, China’s Shanghai Composite (SSEC) seem to be “diverging” alongside with other Asian markets as the Nikkei or Asia ex-Japan. As US markets seem testing the lows, Asian markets appear to be holding ground.

Likewise, the SSEC seems to have been boosted by the National Bailout program. But as we have earlier mentioned the SSEC have been treading in historical bottom pattern which makes the 1,719 area a strong support level.

As we have long mentioned, it has been a longstanding bias of mine that the Asian markets are likely to recover first considering the impact from the present crisis have been one emanating from the periphery than from the epicenter.

Put differently, Asian markets have borne the brunt of the contagion than as source of the crisis. Fundamentally speaking, many factors favor a recovery in the Asian markets (less debt or leverage in both internal and external liabilities, sizeable currency reserves, demographic advantage, growing middle class, significantly improving productivity, rising income and etc.).

But one or two weeks doesn’t a trend make.

So we will have to stay in the sidelines and watch for further confirmations.