As I said last week, rising stock prices on a slew of internal and external bad news usually signifies as bullish indicators.

Here is what I wrote,

Foreign trades have also been sluggish with paltry changes over the last two weeks. Yet, despite the marginal actions by foreign investors, the Philippine Peso posted modest advances.

So essentially, last week’s action suggest of a rotation away from second and third tier issues back into the blue chips.

Yet I expect to see normalization of trading activities in terms of Peso volume which should undergird either the current consolidation phase or a fresh attempt to break away into new highs.

When the markets to defy the spate of bad news that signifies as a bullish signal.

Speaking of luck that’s exactly how it turned out the week!

First of all, the Phisix broke into fresh nominal record high even as the Scarborough issue has not been resolved.

As an aside, I would reiterate that for whatever innuendos about resources alluded by media, the Spratlys-Scarborough issue has not been about oil or commodities but more about unspecified political agenda which could be related to promoting arm exports or ploys to divert the public from festering real political issues or as justifications for inflationism.

I might add that the heated kerfuffle over territorial claims has expanded to cover the disputed Senkaku Islands, where Japanese authorities has jumped into the fray to announce of their acquisition of the island from the “owners”. This has resulted to a political backlash from Chinese authorities.

Given that politics in Japan seems to have been entangled with monetary policies, Japan’s recent provocative foreign policy posture could be portentous of Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) moves to expand its stimulus (via asset purchases), perhaps under the pretext of increasing military spending.

Going back to the Philippine stock market, given the record performance, we can’t discount the prospects of interim ‘profit taking’. But again I think momentum still favors the bulls.

Second, net foreign trade has turned significantly positive mostly bolstered by the GT Capital’s listing last Friday

Third market breadth also turned positive…

…as advancing issues took the driver’s seat anew.

If the positive momentum, which is likely to be reflected on the actions of the benchmark Phisix should persist, then we would see a broadening of gains over the broader market.

Most of the gains had been concentrated on the sectoral leaders since the start of the year, particularly, property, finance and holding companies or mother units of the former two.

I think that rotation will occur among the heavyweights as the current leaders may take a short reprieve.

Importantly the Peso volume DID normalize…

Daily traded Peso volume (averaged weekly) surged amidst as last week’s record breakout.

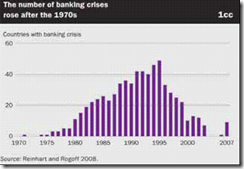

I see a continuity of the bullish or upside momentum of the financial markets which may last until the first semester of the year, where central bank steroids are due for expiration. While this may lead to an interim volatile phase perhaps backed by deteriorating economic or financial conditions in Europe or in China, we should expect downside volatility to be met by aggressive responses from central bankers. This feedback mechanism between markets and central bank interventions has not only been made to condition the markets, but has become the central bankers’ guiding policy of crisis management.

BSP’s Euthanasia of the Rentier

This dogmatic approach has been assimilated even by the local central bank, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP).

Just last week, domestic interest rate policies have been kept at “historics” lows whose levels were justified as “sufficient to help boost economic activity and avoid potential spike in inflation amid volatile global oil prices”.

The BSP blames external factors as secondary variables of domestic inflation through a “likely rise in foreign portfolio investments and higher prices of electricity amid petitions for further power-rate increases.”

In reality, interest rates policies that has driven been to superficially “historic” lows that are financed by “money from thin” are the real cause of inflation

Austrian economist Dr. Frank Shostak explains,

The exchange of nothing for something that the expansion of money out of "thin air" sets in motion cannot be undone by an increase in the production of goods. The increase in money supply — i.e., the increase in inflation — is going to set in motion all the negative side effects that money printing does, including the menace of the boom-bust cycle, regardless of the increase in the production of goods.

And symptoms from BSP’s actions have been manifesting on the domestic credit markets. Notes the Inquirer.net

True enough, credit growth so far this year has been robust. As of February, data from the central bank showed that outstanding loans by universal and commercial banks grew by 18 percent year on year to P2.74 trillion. The BSP said the increase in bank lending benefited both individual and corporate borrowers.

A boost in bank lending is not “a one-size-fits-all” thing.

A boost in bank lending that has NOT been prompted by consumer preferences but from the skewing price signals due to political “money printing” policies designed to achieve quasi permanent booms leads to bubble cycles.

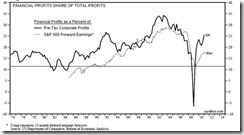

And what is deemed as “robust growth” by media are, in reality, signs of malinvestments and speculative diversion of productive capital. Some of these borrowed money will find their way to the local stock exchange, real estate properties, bond markets and much of which will be diverted into consumption spending or misallocated capital that leads to capital consumption.

And adding to the policies of the promotion of “aggregate demand” or “the euthanasia of the rentier” through “historic” low interest rates has been the announcement by the local version of the welfare state, the Social Security System (SSS), to lower interest rates and to increase loanable amount to members for housing loans.

Apparently, little has been learned by local political authorities of the lessons from the latest US centric political homeownership crisis that has diffused across the world and whose phantom continues to haunt the political economies of the developed world.

Noble intentions eventually get burned by politically instituted economically unfeasible projects.

Sell In May?

Fund manager David Kotok of Cumberland Advisors rightly points out the differences in the current environment from yesteryears, such that seasonal statistical patterns like Sell in May and Go Away may not be relevant to current conditions.

History shows that ‘Sell in May and go away’ has applied when the Federal Reserve was in a tightening mode during the six-month span from May to November. If the Fed was actively raising interest rates, withdrawing or constricting credit, imposing additional reserve requirements, or taking an action that was of a tightening mode, stock markets were usually punished in that six-month period.

When we did the study we examined what the Fed did, not what it said. We used actual changes in the Federal Funds rate to determine whether the Fed was tightening, easing, or neutral. Once the Fed took the interest rate to zero at the end of 2008, the historical data series lost its power for forecast purposes, since the Fed cannot take the rate below zero. However, we believe the concept is valid even if the present measurement problem exists.

It is human action and NOT charts (for example the failed death cross pattern of the S&P 500 of 2011) or seasonal patterns, based on either statistics or historical outcomes, that determines future outcomes.

The substantial impact of central bank policies on the markets has been through the manipulation of money. Since money is a medium of exchange which represents half of every transactions people make, tinkering with money has greater tendency to alter or reshape the incentives of people.

Manipulation of money through inflationism tend to narrow people’s time orientation or increases time preferences which has been and will be ventilated through several attendant actions, as higher inclination to take debt, misdirection of investments via distorted price signals, consumption based lifestyles or pejoratively known as “consumerism”, greater risk appetite or higher inclinations towards speculation.

So when major central banks combine to tamper with money, which among themselves account for about 85% of the capital markets of the world, we can expect participants of the marketplace to adjust accordingly to these newly implemented policies. Current policies have been engendering asset inflation, which in reality has been designed to keep the flagging banking system and the unsustainable welfare states afloat.

Even emerging market central banks, as the Philippines have employed the same policies which are often justified from “growth risk”. Yet despite the standardization of monetary policies, the differences in market outcomes have been resultant to variances of people’s actions relative to the idiosyncratic structural compositions of each political economy.

In addition, while monetary policies have significant effects on people’s incentives other policies also matters such as fiscal policies and tax regimes, rule of law and protection of property rights, trade and economic freedom, and regulatory policies.

The bottom line is all these policies would have a greater impact to people’s action than simply reading numbers and history as basis for predictions.

As the great Ludwig von Mises wrote in Theory and History

Historicism was right in stressing the fact that in order to know something in the field of human affairs one has to familiarize oneself with the way in which it developed. The historicists' fateful error consisted in the belief that this analysis of the past in itself conveys information about the course future action has to take. What the historical account provides is the description of the situation; the reaction depends on the meaning the actor gives it, on the ends he wants to attain, and on the means he chooses for their attainment...

The historical analysis gives a diagnosis. The reaction is determined, so far as the choice of ends is concerned, by judgments of value and, so far as the choice of means is concerned, by the whole body of teachings placed at man's disposal by praxeology and technology.

Along the lines of the Professor von Mises, my former idol the exemplary stock market guru but who now has been converted to a crony, Warren Buffett, once lashed out at the tendency of people to anchor or rely heavily on past performance. The ailing 81 year old billionaire Mr. Buffett said

If past history was all there was to the game, the richest people would be librarians.