The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of ready-made answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.—Joan Robinson

In this issue

Phisix Mania Rages As Money Supply Sizzles for the 9th Month!

-NINE Consecutive Months of 30+% Money Supply Growth

-Argentina Paradigm Redux; The Social Tipping Point

-Bait And Switch Is Part Of The Signaling Channel Of Central Banks

-Artificial Demand from the Boom Bust Cycle

-Phisix: Don’t Think With Your Eyes

Phisix Mania Rages As Money Supply Sizzles for the 9th Month!

My rice supplier raised prices of my sinandomeng 25 kg sack by 4.34% this week. This will be the second price increase during the last three quarters.

NINE Consecutive Months of 30+% Money Supply Growth

For the NINTH consecutive month, the Philippine money supply growth juggernaut continues. For March, domestic M3 grew by still shocking 34.8% year-on-year which was slightly off the revised February figure of an even more terrifying 36.1%. We are talking of 30+% money supply growth, which has been more than triple the statistical growth figures! Paradoxically the GDP data has been underpinned by the same fantastic rate of money supply.

Where exactly has the bulk of money supply flowed into? Let us read this from the Philippine central bank, the Bangko ng Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) report[1], “Domestic claims rose by 12.4 percent in March as bank lending accelerated further, with the bulk going to real estate, renting, and business services, utilities, wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing, as well as financial services.” [italics mine]

Banking sector claims on the private sector and on other financial corporations account for 68% of M3 while claims on the central government represent 17% of the March nominal M3 figures. The BSP concludes with “The growth in domestic liquidity remains consistent with the current pace of expansion in the real sector.”

And how has the banking system’s loan portfolio performed last March? General banking loans grew on a y-o-y basis by 18.1% in March slightly up from February’s 17.8%. How has banking loan growth has been distributed? From another BSP report[2], “The expansion in production loans was driven primarily by increased lending to the following sectors: real estate, renting, and business services (which grew by 19.7 percent); electricity, gas and water (34.9 percent); wholesale and retail trade (22.1 percent); manufacturing (14.1 percent); and financial intermediation (10.5 percent).[italics added]. The BSP adds that the only sector that generated a decline in was the government, particularly the public administration and defense.

Let me complete the list of bank lending growth figures for March on the private sector: Construction 46.67%, Agriculture 8.26%, Fishing 44.3%, Mining and Quarrying 1.28%, Transportation & Communication 1.8%, Education 31.62% and Hotel and Restaurants 41.06%. Loans to the government include Health and Social Work 37.64% and Other Community, Social & Personal Services 32.12%. Let me add that the fishing sector’s astonishing growth rate only commenced in July of 2013, while the double digit growth in the Education sector has been only 5 month old.

Almost similar to the liquidity report the BSP concludes, “The sustained growth in bank lending reflects robust domestic demand”.

As noted above, the banking sector’s massive credit expansion has been responsible for most of the growth in money supply. It must be realized unless borrowers stash these money under the proverbial mattress which is unlikely given the cost of borrowing, all these newly money created represents fresh nominal spending power. And such huge amount of additional purchasing power will compete to bid up on goods and services that will affect relative prices, economic coordination and relative supply balances.

In other words, if the supposed “robust domestic demand” is hardly matched by an equally “robust” domestic supply growth then systemic risks are being magnified through the inflation, interest rate and credit channels. Yet the longer such outrageous rate of money supply growth is maintained, the larger the build up of imbalances and the bigger risks of a financial and economic destabilizing “shock”.

Argentina Paradigm Redux; The Social Tipping Point

The Philippines money supply growth rate as I previously pointed out[3] has now reached the levels of Argentina’s terrifying money supply growth rate. The difference between the Philippines and Argentina has been in the means of attaining the end or the goal—government access to credit.

Since the financing of Argentina’s government extravagance has been limited, which has been a legacy from her past crisis and in response to the increasingly protectionist regime, the Argentine government has been monetizing these seen via money supply growth—thus the government spending bubble.

On the other hand, the Philippines has successfully mounted a publicity campaign to project a political economic “transformation”, via symbolical anti-corruption crusades, and most importantly, through an economic pirouette which in 2009 embraced a negative interest rate regime to purportedly stoke domestic demand in order to reduce external dependence[4].

In reality such policies has been engineered as subsidies to the government.

Negative interest rates have vastly inflated revenues, earnings, incomes and asset prices from asset bubbles pillared on credit inflation financed government expenditures, as well as, helped pushed the Philippine government debt servicing cost lower than it would be in a free market. Such transfer mechanism has been mainly channeled through the massive debt accumulation in the private sector, even as government debt has been cosmetically contained—thus the bubble economy. Such unstable debt accretion is now being ventilated on the absurd rate of money supply growth.

As you can see from the BSP data, since the money supply growth has been mostly bank credit to the private sector, particularly to the massive supply side expansion, curtailment of these will put a kibosh on the artificial demand. This is something which statisticians cum economic analysts won’t see.

So the economic outcome will be different for both countries applying the same inflationism through different means. For Argentina the likely outcome will be hyperinflation. For the Philippines the scenario will be—following every artificial boom—a bust. So for me, I fear the boom because of the bust it brings.

However if the Philippine government monetizes her spending (via bailouts) ala Argentina, in wake of the bust, then the risks shift towards hyperinflation.

Yet the social cost of inflationism will be the same.

I have noted last week that many of Philippine media networks have implicitly been brainwashing the public towards a collectivist “mob” mindset.

In the political system, particularly the social democratic system, the mob represents votes. For politicians, pleasing the mostly tax consuming mobs means securing the votes for a political office. For private sector rabble rousers connected to the politicians, parts of the economic pie will be rewarded to them in support of their rationalization for interventions. Therefore, populist politics extrapolates to the shaping or conditioning of the mobs’ morality to justify policies of legal plunder via coercive redistribution.

Yet the rule of a mob is a common feature of society enduring financial and economic repression. Argentina should be a wonderful example, rising crimes rates have led to a backfire of the dictatorship based on mob rule. Rising cases of vigilantism against criminals have gone beyond control of the political authorities[5]. This is a manifestation of how inflationism destroys the society’s moral fabric. This can be called as the social tipping point or where government loses control of the people[6]. A politically dependent constituency deprived of what they have believed as entitlements because of lack of resources, take matters on their own hands and eventually lashes back at the government.

Push inflationism beyond the scope of societal tolerance and we will see violence as ramification.

For the don’t worry, be happy crowd, despite the resumed decline of the Argentine peso following a early year rally based on the black market rates, Argentine’s equity benchmark, the Merval index, has been up 25.8% year to date, which represents returns a little above the implied inflation rates.

Bait And Switch Is Part Of The Signaling Channel Of Central Banks

Another issue I would like to raise is the flaw in the assumption that debt is natural for business or in the BSP context, a theme which has been embraced by worshippers of bubbles, “The sustained growth in bank lending reflects robust domestic demand”

For me such claim represents the fallacy of the average or the fallacy of composition.

Let me make a simple analogy. A polling firm desiring to establish the average wealth of a people in the particular area will conduct a survey by randomly interviewing 10 people on a given street at a particular time. What happens if the one of the randomly chosen person turned out to be one of the Philippine list of Forbes billionaires? The average wealth for the 10 interviewed people will soar, thereby skewing the average!

This applies when the BSP looks at the 18.1% y-o-y general loan growth and proclaims that “sustained growth in bank lending reflects robust domestic demand”. The average of the 18.1% growth rate has been brought about by a combination of high flyers—which has pulled the average higher—mainly the bubble sectors: Construction 46.67%, Hotel and Restaurants 41.06%, wholesale and retail trade 22.1, and real estate, renting, and business services 19.7% aside from some areas supporting the bubble sector, manufacturing 14.1%, electricity gas and water 34.9% and Education 31.62%— and index draggers or these that have pulled the index lower particularly Agriculture 8.26%, Transportation & Communication 1.8% and Mining and Quarrying 1.28% and even bubble sector financial intermediary 10.52%.

Out of the 12 non-government sectors, 7 (58.3%) have posted gains above 18% thus raising the average while 5 (41.67%) have pulled down the average. Considering the vast disparity of growth rates, how can this be representative of the claim that such lending growth “reflects robust domestic demand”? Because of the majority or 58%? If so then this represents politics in terms of data interpretation.

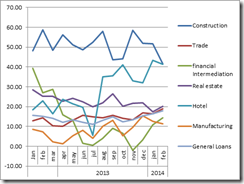

The reality is that what have been consistent has been the growth rates of what I deem as the bubble areas: real estate, renting, and business, construction, hotel and restaurant (casino), wholesale and retail trade (shopping mall) and financial intermediary (right pane).

In 2012 the share of these industries relative to the overall banking loans has been at 47.47%. Last year’s spike in money supply growth pushed their share to 49.61%. That’s a 2.14% growth in terms of billions of pesos. As of the March data based on the BSP’s April report, the bubble sector’s share has surpassed halfway threshold mark now at 50.31% (see left pane). And as of the end of 2013, these bubble areas contributed to 44.84% share of the Philippine statistical GDP.

The implication is that instead of bank lending reflecting on “robust domestic demand” what we have here are more evidences of sustained increases in specific demand that reflects on the deepening concentration of benefits and risks of certain sectors relative to the overall bank lending.

As of December 2013, the total loan portfolio of the Philippine banking system (net of allowance for credit losses) of the Philippine banking system, according to the BSP, represents 47.5% of the total financial resources at Php 9.971 trillion. The increasing concentration of banking risks will eventually put to the test the much ballyhooed bank capital to asset ratio of 11.2.

The hallmark 2009 pirouette by the BSP can also be seen in an equally amazing growth trend of BSP’s assets. Over the past 5 years, BSP’s assets have posted an annualized compounded growth of 10.36%. But since the BSP contrived of the Special Deposit Account growth (SDA) in 2006[7] annualized growth has even been more (13.08%)! So this affirms my suspicion that the BSP has been expecting a credit inflation driven economy even before the official shift in 2009.

Paradoxically if we apply the same bank capital to asset ratio on the BSP, with capital at only Php 40 billion compared with assets at Php 4.202 trillion (December 2013) the ratio would extrapolate to a mere .95%! Only 40 billion pesos backing all those trillion peso claims! So it would seem that the BSP has even been more leveraged than the banking sector, it controls!

Yet with the increasing share or concentration of banking loans to specific areas, the implication is that these will be reflected on GDP share too.

Why? Because credit expansion means additional nominal buying power. Period. And more spending power means that these sectors will have the ability to acquire more resources relative to, and away from, the other sectors. The fresh spending power thus will extrapolate to more GDP activities for these sectors.

Yet what mainstream will not tell is you is that since resources are scarce, every human activity involves opportunity costs—or the cost of a choice[8].

Take cement as an example. Unlike credit where money is created through deposits instantaneously upon the decision of the banker, raw materials of (Portland) cement are mined (limestone, clay, gypsum) and processed in a kiln through a process called calcination. The resulting substance called ‘clinker’ is grounded with gypsum to make ordinary Portland cement[9]. In short, for a cement to be produced, this requires entrepreneurial incentive to profit from its production, as this would take time, effort and money to be invested in the process.

Thus when cement has been produced, forces of demand and supply determines how the cement be priced for sale and accordingly how much to be produced by suppliers in the future.

In the current setting where there has been a plethora of money chasing specific goods for particular projects, the opportunity cost of a cement acquired for use by the property sector is a cement that could have been used by the mines, agriculture or transportation and communication.

Thus the boom in the property and property related sectors means gargantuan amount of resources funneled, diverted and committed to the bubble areas at the expense of non-bubble areas. This also denotes that instead of the “sustained growth in bank lending reflects robust domestic demand”, this reflects on “robust” specific domestic demand rather than an overall demand.

The intensifying concentration of credit expansion to bubble sectors will reduce available relative supplies to other non-bubble sectors. The implication is that the latter will register lower growth rates relative to the bubble sectors. This includes not only domestic enterprises targeting domestic consumers but includes as repeatedly discussed, enterprises catering to non resident based international consumers[10]. The alternative will be to source resources from overseas, thus putting pressure to the trade balance.

As evidence, a publicly listed company which posted record profits in 2013 noted that aside from other pat on the back attribution of “good price management and steady volumes on the continued growth of cement demand”, cement market growth had been “made robust by the government’s heavy investments on infrastructure and the private sector’s commercial, residential and industrial projects.” This reveals where the absorption of most cement products have been.

And when I talk about insufficient domestic supplies that would require for external sourcing due to expanded demand, the same report explains that “as the construction industry posted another double-digit growth”, the company has “resorted to importing clinker”[11]

[As a side note, I omit the company’s name in order to focus on issues. Details can be found in the foot notes.]

Furthermore last February, reports of incidences of unauthorized cement price increases has compelled to the Philippine government via the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) to “intensify its monitoring of cement prices”.[12] What this posits is that there has been increasing black market activities in cement transactions, as the current regulated or controlled prices do not reflect on actual fired up demand, which ironically, both industry people and authorities ironically recognize.

While the Philippine government cherishes the inflationary boom, they hope that the laws of economics will be suspended by fiat or by political controls—the King Canute dynamic. Yet if input prices continue to rise, that will be aggravated by the falling of the peso, this will crimp on profits of cement producers and other related construction materials, if politically controlled prices are to remain at current levels. Price controls will lead to shortages and will annul the ecstatic effects of inflationism on the bubble areas.

Inflationism and price controls are twin siblings. Governments everywhere through history[13] have continually raised strawmen (epitomized by the sloganeering of ‘consumer protection’) which they try to beat down by instituting price controls. Governments essentially divert the issue by shifting the burden of the adverse effect of money creation to the non-political general public. But the problem hasn’t really been the private sector, but rather, governments habitually engaged in inflationism to finance their overindulgences.

So price controls are really showbiz or publicity stunts. They are also signs of self contradictory policies. Yet what the blossoming black market suggests is that price inflation on cement products has been seething underneath. Yet this has not been accurately represented in government statistics due to price controls. And yet the strains in cement pricing and supply are just one of the many emerging symptoms of how the Philippine government has underwritten the downfall of her bubble economy.

And speaking of publicity stunts, in the eyes of the Philippine government, the usual culprit for the domestic inflation has been the supply side. And even if they discuss about demand, they cite a litany statistics without having to elucidate how such events evolve, as if things just occurs.

Here is an example. From the BSP[14]: Real gross domestic product (GDP) expanded by 6.5 percent in Q4 2013, bringing the full-year 2013 GDP growth to 7.2 percent, higher than the National Government’s growth target of 6.0-7.0 percent for the year. Output growth was driven by robust household spending, exports, and capital formation (particularly durable equipment) on the expenditure side, and by solid gains in the services sector on the production side. Indicators of demand in Q1 2014 continue to show positive readings. Vehicle and energy sales remain brisk, while the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) continues to signal strong growth in new orders and production, especially in the services sector.

What drove the following: robust household spending, exports, and capital formation or vehicle and energy sales? Mere animal spirits?

For political economies that seeks to see price inflation like Japan, did Prime Minister Shinzo Abe order supply side constrains to boost inflation? The answer is no. What PM Abe did was to have the Bank of Japan’s governor Haruhiko Kuroda generate a 2 percent target inflation rate through quantitative easing[15] by doubling the monetary base[16]

The initial result has been to balloon a stock market bubble. Unfortunately given that one of the three arrows—the monetary policy arrow—has been halfway the target, Japan’s year on year M2 growth seem to have fizzled out. And the creature of the doubling of monetary base—the Japanese stock market bubble via the Nikkei (right)—seem to have corresponded nearly symmetrically with the year on year changes of the money supply.

Now Japan’s Wall Street has been desperately hoping that BoJ’s Kuroda will introduce more quantitative easing if not an extension!

But with the recent imposition of sales taxes last April which most likely will have a negative impact on Japan’s economy over the long run combined with likely scenario that the BoJ withholds from expanding Abenomics…watch out! As a side note I think that the BoJ will eventually extend but again there is no free lunch and inflationism will hit a natural [economic or political] limit

The point here is that if a government publicly desires to achieve inflation they not only do it, they officially proclaim it as a public policy which they call as inflation targeting. But if a government wants to suppress or hide inflation, they throw all kinds of statistical camouflages or simply “pull a wool over the eyes” of the public on their misdeeds.

In short, most governments, I believe, know about the risks of inflationism. This means that bait and switch plays a vital part of the evasive signaling channel of central banks.

Artificial Demand from the Boom Bust Cycle

As pointed above the 30+% money supply growth has not just been a bank lending phenomenon but about the deepening concentration of risks in the Philippine economy.

For most of the mainstream, they hardly understand how such inflationism translates to artificial demand and how artificial demand reinforces the risks.

Unlike other sectors, the bank credit growth to the property and property related sectors have been steadily on the rise since 2007. From 2007 to 2013 the real estate industry has been a consistent and largest beneficiary of bank credit inflation, followed by trade and financial intermediation. Credit to the construction industry only picked up in 2011 onwards.

Let me explain how the boom bust cycle works.

The easiest way to generate an artificial credit fueled boom is via the property sector. This is because land supply is fixed. In response to artificially lowering of the interest rate (negative real rates), when the banking sector expands credit relative to the land supply, the value of land increases. And increases in the value of land likewise increases assets of companies backed by land. Aside from the normal course of commercial activities, higher asset values encourage manifold transactions such as mergers and acquisitions, capex expansions and various arbitraging activities. Thus amidst an easy money landscape, higher asset values promotes borrowing and lending in support of these activities.

In his reflexivity theory, the billionaire George Soros notes that “Banks base their lending on the value of collateral; but the act of lending can also influence value. When people are eager to borrow and the banks are willing to lend, the value of the collateral rises in a self-reinforcing manner and vice versa”[17]

g

This also means that under an easy money landscape, early recipients of borrowed money would benefit via profits from intertemporal price spreads as a result of sustained bank credit expansion. A popular stock market maxim “buy high, sell higher” appears to be emblematic of such Cantillon effect of bank credit inflation as well as the reflexivity theory. This applies not only to the stock market but to the interest rate sensitive sectors as banks (lending based on the steep yield curve), property and property related sectors. And part of the ensuing profits from arbitraging price spreads will be spent on consumption and part of the profits will be used for reinvestments. Retained earnings will likely be complimented by more borrowing to finance expansions at the early phase of the cycle. This should represent what Hyman Minsky calls as Hedge financing—the ability to fulfil all contractual payment obligations[18].

So as the credit cycle progresses, we see sustained increases in the value of property and the ballooning of profits and earnings. Both inflated asset values and inflated profits and earnings augment consumer demand.

Besides, reinvestments from the booming phase are likely to entail more hiring where the increased demand for employment extrapolates to higher wages for employees of the said booming sectors. Consumer demand has now been boosted from inflated asset values, earnings and profits, wages and increased employment. But the boom progresses along with an acceleration of debt accumulation.

Big profits/earnings and high wages draw in more players into the industry as the intemporal price arbitraging remains highly profitable. Competition now forces existing players to undertake more forceful steps in order to squeeze profits or to capture market share. Using the same activities but with more intensity, market players imbibe on more debt at a faster and riskier phase. Reinvestments financed by retained earnings diminish as mostly debt and or partly equity issuance take over. While consumer demand grows along with debt, the latter grows at a faster rate.

In this phase the credit cycle has evolved from hedge financing to speculative financing where many companies can meet only interest liabilities and not the principal. Yet the outgrowth in demand for resources begins to put a strain on input prices and competition for access on credit also begins to put pressure on interest rates. Competition for resources will also extrapolate to more imports that lead to trade deficits and eventually current account deficits. The domestic currency begins to weaken.

The final phase of the boom is when companies in desperation to keep profits or market share take on wild reinvestment activities as rational valuations are thrown out of the window. The financing requirements of many companies have now entirely been dependent on debt and partly through equity issuance. Banks and other lenders have significantly lowered credit standards to accommodate the frenzied borrowing pace.

Over at the financial markets the same irrationality consumes market participants who aggressively bid up on asset values financed by debt. Debt levels for many companies hit perilous levels having to entirely depend on sustained low interest rates. The same companies can hardly pay for both interest and principal liabilities but totally depends on debt rollover and offloading of asset prices—the Ponzi finance.

Intense competition for resources leads to price inflation becoming more pronounced for input prices. Consumer price inflation may or may not accompany inflation in input prices. Interest rates move higher on such account. Large increases in the demand for credit also compounds on interest rate movements. Deficits in trade and current account balances also add to interest rate pressures. The weakening of the currency worsens. Higher inflation rates pose as an obstacle to demand. Higher interest rates reduce debt issuance, increase the burden of debt servicing and put pressure on all activities that has been enabled by bank credit inflation based on easy money policies.

The feedback loop in between debt and commercial activities gets amplified. Increasing debt problems impact economic activities via a slowdown. And a slowdown in economic activities exacerbates debt conditions. Debt problems surface at the fringes, then spreads and expands to impact the core. Margin calls increase in frequency. Banks and other creditors hobbled by growing non performing loans curtail lending. Companies pressed to raise payments go on a liquidation mode. Mr Soros’ reflexivity relationship between collateral values and lending go on a reverse. Economic activities are impeded by liquidity and solvency issues. Consumer demand is further constrained by economic slowdown and limited access to credit. The liquidation mode intensifies. Currencies dive (this applies to emerging markets). Mania turns into Panic. The boom morph into a bust.

Consumer demand hardly plays the crucial role in the boom bust cycles but usually displays symptoms of the process.

Look at how Philippine consumers performed during the current boom. Let us assume first that this data is valid or accurate. I will not be dealing here with growth rates but rather on the changes of the assumed distribution share of the Philippine households from 2011 to 2013 according to the data from the National Statistical Coordination Board.

Has the disposable income of residents of the Philippines increased? The answer is no. Despite the ‘robust’ growth rates, domestic households have spent about 42+ cents of every peso in food, 12+ cents in housing and household utilities and 10+ cents to transport. For the 3 sectors in 2011 they contributed to 65.9 cents for every peso spent. In 2013 this signified 65.7 cents for every peso. Such .2 cents improvement has been statistically insignificant.

So with money supply growth rate in a tear at 30+%, expect that whatever gains over the past 3 years will more than reverse as the average residents will increasingly spend more on necessities as disposable income shrinks. So hope that the above government statistics understates the real position of the domestic households.

As a side note, I will add to my observation I made last week on the Philippine Foreign Direct Investments, where I noted that “Philippine government prefers to remain a closed economy through a suffocating web of regulations via a nationalist Foreign Ownership Restrictions”[19]. The Philippine government will always say things to promote their interest. So it pays to observe on what they do (demonstrated or revealed preferences) rather than what they say.

In January of 2014, the Philippines posted a net inflow of $1 billion of FDIs according to the BSP where 67% flowed into debt while the rest into equities. Most of the debt based inflow comes from parent companies abroad lending to local affiliates supposedly “to fund existing operations and the expansion of their businesses in the country”. Perhaps true or perhaps some of that money found their way on stock market speculation. Yet the BSP doesn’t say which industries benefited from the inflows.

The equity portion of FDIs had been more explicit. From the BSP[20], “The bulk of gross equity capital placements—which originated mainly from Hong Kong, the United States, Japan, Singapore and the United Kingdom—were channeled mainly to financial and insurance; wholesale and retail trade; real estate; manufacturing and information and communication activities” The World Bank noted that large retailers and casinos were the only beneficiaries from the selected liberalization of Foreign Ownership Restrictions. Yet the equity capital placements validate my view that current FDI figures have been meant to accommodate the bubble sectors.

Phisix: Don’t Think With Your Eyes

The Phisix continues to exhibit ferocious signs of intense mania. Bulls have seen Philippine stocks as a one way trade—predestined to reach nirvana. Not even a correction seems to be permitted; although the recent fierce rallies have come in the face of dwindling volume.

The excessively overbought blue chip stock index encountered a second “marking the close[21]” for the year where some parties seem to have decided that the local benchmark should close at 6,700 for the month of April. How was this done? By pushing the company with the largest weighting PLDT. Managing the ticker tape is a sign of intensifying desperation rather than of a salutary bull market.

Such signs are clearly denial rallies in progress.

As a wrote back in June of 2013[22]

“Denial” rallies are typical traits of bear market cycles. They have often been fierce but vary in degree. Eventually relief rallies succumb to bear market forces.

Analyst Doug Noland of the Credit Bubble Bulletin has a swell description of the denial rallies[23],

Markets are fascinating creatures. Speculative marketplaces, if not suppressed, inherently regress into wild animals. And over the years I’ve drawn an analogy between speculative Bubbles (“bull markets”) and bull fights. After the bull is penetrated by that first sword, the eventual outcome is in little doubt. Yet before succumbing he’s going to turn crazy wild and inflict as much damage as possible.

During the last topping phases that led to the bear markets of 1997 and 2008, the Phisix regained all the previous losses but failed to break beyond to a new high. The rest is history. Will the Phisix make a replay of the past; hit 7,400 before entering a full bear market? Maybe or maybe not. But I won’t bet on it.

The 9 month 30+% money supply growth rates combined with the outrageously mispriced or excessive overvalued stocks where financial ratios have been reminiscent of the pre 1997 crash are enough to demonstrate of existence of massive malinvestments that are due for market clearing. What has driven financial assets to such ridiculous levels? The answer has been explained above.

As in the 1994-96 experience extremely valued securities end up with negative real returns—where nominal losses will be compounded by a reduction of purchasing power. And considering that unlike 2008 where the Philippines had little imbalances compared to today, recovery will take time. The Phisix bottomed 6 years after the Asian crisis.

Over the interim stocks may continue to move higher, but any event—exogenous or endogenous—may trigger a sharp reversal of optimism

In the movie Karate Kid 2010, after Dre “the Karate Kid” Parker (Jaden Smith) was rescued by his would be mentor Mr. Han (Jackie Chan) from his mauling by 6 martial art bullies, the stunned boy remarked at the latter’s demonstration of martial arts expertise “I thought you were just a maintenance man.”

Mr. Han replies,

You think only with your eyes, so you are easy to fool.

[1] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Bank Lending Continues to Grow in March April 30, 2014

[2] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Bank Bank Lending Continues to Grow in March April 30, 2014

[3] See Phisix Melts Up as Money Supply Growth Sizzles for the Eight Month April 7, 2014

[4] See Phisix: In 2009, the BSP Engineered a Crucial Pivot to a Bubble Economy April 14, 2014

[5] RT.com Buenos Aires declares state of emergency to combat ‘mob justice’ April 9 2014

[6] Jeff Thomas The Social Tipping Point International Man April 28, 2014

[7] See Phisix: Escalating Risks from the Region and from Internal Bubbles December 9, 2013

[8] Wikipedia.org Opportunity cost

[9] Wikipedia.org Cement Types of modern cement

[10] See Phisix: BSP’s Response to Peso Meltdown: Raise Banking Reserve Requirements March 31, 2014

[11] Manila Bulletin Holcim posts record P4.55-B profit in 2013 Yahoo.com February 21, 2014

[12] GMAnewsnetwork.com DTI to monitor cement prices daily over reports of price increases February 7, 2014

[13] Robert L Schuettinger and Eamonn F. Butler Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls Heritage Foundation Mises.org

[14] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Inflation Rises in Q1 2014 But Remains Within Target April 28, 2014

[16] See BoJ’s Kuroda’s Opening Salvo: 7 trillion yen ($74 billion) of Bond Purchases a Month April 4, 2013

[17] George Soros The Alchemy of Finance John Wiley & Sons p 23

[18] Hyman P Minsky The Financial Instability Hypothesis* Levy Institute May 1992

[19] See Phisix: The Showbiz Political Economy and the Showbiz Financial Markets April 28, 2014

[20] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Foreign Direct Investments Inflows Reach US$1 Billion in January 2014 April 10, 2014

[21] See Phisix: Second Month End ‘Marking the Close’ in 2014 April 30 2014

[22] See Phisix: Don’t Ignore the Bear Market Warnings June 30, 2013

[23] Doug Noland Serial Booms and Busts Credit Bubble Bulletin May 2, 2014 Prudentbear.com