This post is the second in a three-part series

In this Issue

Gold’s Record Run: Signals of Crisis or a Potential Shift

in the Monetary Order?

I. Global Central Banks Have Driven Gold’s

Record-Breaking Rise

II. A Brief Recap on Gold’s Role as Money

III. The Fall of Gold Convertibility: The Transition to

Fiat Money (US Dollar Standard)

IV. The Age of Fiat Money and the Explosion of Debt

V. Central Banks: The Marginal Price Setters of Gold

VI. Is a U.S. Gold Audit Fueling Record Prices?

Gold’s Record Run: Signals of Crisis or a Potential Shift in the Monetary Order?

The second part of our series examines the foundation of the global economy—the 54-year-old U.S. dollar standard—and its deep connection to gold’s historic rally.

I. Global Central Banks Have Driven Gold’s Record-Breaking Rise

Global central banks have played a pivotal role in driving gold’s record-breaking rise, reflecting deeper tensions in the global financial system.

Since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, central banks—predominantly those in emerging markets—have significantly increased their gold reserves, pushing levels back to those last seen in 1975, a period just after the U.S. government severed the dollar’s link to gold on August 15, 1971, in what became known as the Nixon Shock.

This milestone reminds us that the U.S.

dollar standard, backed by the Federal Reserve, will mark its 54th

anniversary by August 2025.

Figure 1

The accumulation of

gold by central banks, particularly in the BRICS nations, reflects a

strategic move to diversify away from dollar-dominated reserves, a trend that

has intensified amid trade wars, sanctions, and the weaponization of finance,

as seen in the freezing of Russian assets following the 2022 Ukraine invasion. (Figure 1, upper window)

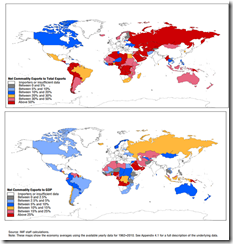

The fact that emerging markets, particularly members of the BRICS bloc, have led this accumulation—India, China, and war-weary Russia have notably increased their gold reserves, though they still lag behind advanced economies—reveals a growing fracture in the relationship between emerging and advanced economies. (Figure 1, lower graph and Figure 2, upper image)

Figure 2

Additionally, their significant underweighting in gold reserves suggests that BRIC and other emerging market central banks may be in the early stages of a structural shift. If their goal is to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar and close the gap with advanced economies, the pace and scale of their gold accumulation could accelerate (Figure 2, lower chart)

Figure 3

As evidence, China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), continued its gold stockpiling for a fourth consecutive month in February 2025. (Figure 3, upper diagram)

Furthermore, last February, the Chinese government encouraged domestic insurance companies to invest in gold, signaling a broader commitment to gold as a financial hedge.

This divergence underscores a deepening skepticism toward the U.S.-led financial system, as emerging markets seek to hedge against geopolitical and economic uncertainties by strengthening their gold reserves

In essence, gold’s record-breaking rise may signal mounting fissures in today’s fiat money system, fissures that are being expressed through escalating geopolitical and geoeconomic stress.

II. A Brief Recap on Gold’s Role as Money

To understand gold’s evolving role, a brief historical summary is necessary.

Alongside silver, gold has spontaneously emerged and functioned as money for thousands of years. Its finest moment as a monetary standard came during the classical gold standard (1815–1914), a decentralized, laissez-faire regime in Europe that facilitated global trade and economic stability.

As the great dean of the Austrian School of Economics, Murray Rothbard, explained, "It must be emphasized that gold was not selected arbitrarily by governments to be the monetary standard. Gold had developed for many centuries on the free market as the best money; as the commodity providing the most stable and desirable monetary medium. Above all, the supply and provision of gold was subject only to market forces, and not to the arbitrary printing press of the government." (Rothbard, 1963)

However, this system was not destined to endure. The rise of the welfare and warfare state, supported by the emergence of central banks, led to the abandonment of the classical gold standard.

As Mises Institute’s Ryan McMaken elaborated, "This system was fundamentally a system that relied on states to regulate matters and make monetary standards uniform. While attempting to create an efficient monetary system for the market economy, the free-market liberals ended up calling on the state to ensure the system facilitated market exchange. As a result, Flandreau concludes: ‘[T]he emergence of the Gold Standard really paved the way for the nationalization of money. This may explain why the Gold Standard was, with respect to the history of western capitalism, such a brief experiment, bound soon to give way to managed currency.’" (McMaken, March 2025)

The uniformity, homogeneity, and growing dependency on the state in managing monetary affairs ultimately contributed to the classical gold standard’s demise.

III. The Fall of Gold Convertibility: The Transition to Fiat Money (US Dollar Standard)

World War I forced governments to abandon gold convertibility, leading to the adoption of the Gold Exchange Standard—where only a select few currencies, such as the British pound (until 1931) and the U.S. dollar (until 1933), remained convertible into gold.

Later, the Bretton Woods System attempted to reinstate a form of gold backing by pegging global currencies to the U.S. dollar, which in turn was tied to gold at $35 per ounce.

However, rising U.S. inflation, fueled by fiscal spending on the Vietnam War and social welfare programs, combined with the Triffin dilemma, led to a widening Balance of Payments (BoP) deficit. Foreign-held U.S. dollars exceeded U.S. gold reserves, threatening the system’s stability.

As economic historian Michael Bordo explained: "Robert Triffin (1960) captured the problems in his famous dilemma. Because the Bretton Woods parities, which were declared in the 1940s, had undervalued the price of gold, gold production would be insufficient to provide the resources to finance the growth of global trade. The shortfall would be met by capital outflows from the US, manifest in its balance of payments deficit. Triffin posited that as outstanding US dollar liabilities mounted, they would increase the likelihood of a classic bank run when the rest of the world’s monetary authorities would convert their dollar holdings into gold (Garber 1993). According to Triffin, when the tipping point occurred, the US monetary authorities would tighten monetary policy, leading to global deflationary pressure." (Bordo, 2017)

Bretton Woods required a permanently loose monetary policy, which ultimately led to a mismatch between U.S. gold reserves and foreign held dollar liabilities.

To prevent a run on U.S. gold reserves, President Richard Nixon formally ended the dollar’s convertibility into gold on August 15, 1971, ushering in a fiat money system based on floating exchange rates anchored to the U.S. dollar.

IV. The Age of Fiat Money and the Explosion of Debt

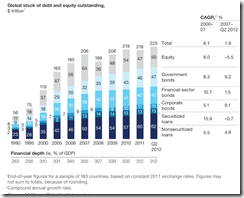

With the shackles of gold removed, central banks gained full control over monetary policy, leading to unprecedented levels of inflation and political spending. Governments expanded their fiscal policies to fund not only the Welfare and Warfare State, but also the Administrative/Bureaucratic State, Surveillance State, National Security State, Deep State, Wall Street Crony State, and more.

The most obvious consequence of this system has been the historic explosion of global debt. The OECD has warned that government and bond market debt levels are at record highs, posing a serious threat to economic stability. (Figure 3, lower chart)

V. Central Banks: The Marginal Price Setters of Gold

Ironically, in this 54-year-old fiat system, so far, it is politically driven, non-profit central banks—rather than market forces—that have become the marginal price setters for gold.

Unlike traditional investors, central banks DON’T buy gold for profit, but for political and economic security reasons.

The World Gold Council’s 2024 survey provides insight into why central banks continue to accumulate gold: "The survey also highlights the top reasons for central banks to hold gold, among which safety seems to be a primary motivation. Respondents indicated that its role as a long-term store of value/inflation hedge, performance during times of crisis, effectiveness as a portfolio diversifier, and lack of default risk remain key to gold’s allure." (WGC, 2024)

This strategic accumulation reflects a broader trend of central banks seeking to insulate their economies from the vulnerabilities of the fiat system, particularly in an era of heightened geopolitical risks and dollar weaponization.

Figure 4

The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) has historically shared this view. (Figure 4, upper graph)

In a 2008 London Bullion Management Association (LBMA) paper, a BSP representative outlined gold’s importance in Philippine foreign reserves—a stance that remains reflected in BSP infographics today.

Alas, in 2024, following criticism for being the largest central bank gold seller, BSP reversed its stance. Once describing gold reserves as "insurance and safety," it now dismisses gold as a "dead asset"—stating that: "Gold prices can be volatile, earns little interest, and has storage costs, so central banks don’t want to hold too much."

This shift in narrative conveniently justified BSP’s recent gold liquidations.

Yet, as previously noted, history suggests that BSP gold sales often precede peso devaluations—a warning sign for the Philippine currency. (Figure 4, lower window)

VI. Is the Propose U.S. Gold Audit Help Fueling Record Prices?

Finally, could the Trump-Musk push to audit U.S. gold reserves at Fort Knox be another factor behind gold’s rally?

There has long been speculation that U.S. Treasury gold

reserves, potentially including gold stored for foreign nations, have been leased out to suppress

prices.

Figure 5

Notably, Comex gold and silver holdings have spiked since these audit discussions began. Gold lease rates rocketed to the highest level in decades last January. (Figure 5, top and bottom charts)

With geopolitical uncertainty rising, central bank gold buying accelerating, and doubts growing over fiat stability, gold’s record-breaking ascent may be far from over.

Yet, it’s important to remember that no trend goes in

a straight line.

___

References

Murray N. Rothbard, 1. Phase I: The Classical Gold Standard, 1815-1914, What Has Government Done to Our Money? Mises.org

Ryan McMaken, The Rise of the State and the End of Private Money March 25,2025, Mises.org

Michael Bordo The operation and demise of the Bretton Woods system: 1958 to 1971 CEPR, Vox EU, April 23, 2017 cepr.org

World Gold Council, Gold

Demand Trends Q2 2024, July 30,2024, gold.org