Investors believe in Keynesianism. They believe that increased government spending will make us all richer. This illusion is what is driving this stock market. Bubbles are based on illusions—Dr. Gary North

In this issue

Important Insights from the Philippine PSEi 30’s Melt-Up!

I. Philippine PSEi 30 Returns Among the World’s Highest

II. Lessons from China’s Previous Easy Money Experiments

III. Market Concentration and Unimpressive Volume and Breadth, Rampaging Philippine Bank Shares and the Lehman-Bear Stearns Experience

IV. Retail Players Emerge

V. Why the Opposite Direction of San Miguel’s Share Prices? Conclusion

Important Insights from the Philippine PSEi 30’s Melt-Up!

What does the outperformance of the PSEi 30 likely mean?

I. Philippine PSEi 30 Returns Among the World’s Highest

The Philippines' primary equity benchmark, the PSEi 30, stretched its weekly winning streak to five with this week’s 0.53% gain.

This week’s gains pushed its year-to-date returns to 15.8% (as of October 4th).

Figure 1

Accompanied by a massive rally in the Philippine peso, the Philippines' ETF, the EPHE, joins the ranks of global top equity ETFs in terms of US dollar returns (as of October 2nd). (Figure 1, upper window)

Year to date, the PSEi 30 ranked fourth in Asia, after Pakistan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. (Figure 1, lower image)

With 16 of the 19 regional benchmarks up by an average of 13.13% in local currency terms, we can generalize that 2024 has been a year of the bulls. Of course, we have two more months to go.

II. Lessons from China’s Previous Easy Money Experiments

Despite recent elevated rates, the current surge in global stocks signifies a product of easy money.

Due to the massive coordinated bailout package unleashed by Chinese authorities to rescue its struggling asset markets (stocks and real estate), Chinese and Hong Kong equities skyrocketed, rising by a stunning 23.4% and 31% over the last four weeks.

However, the returns of China’s equity markets have been capped due to a week-long holiday.

Figure 2

Though many international experts have suddenly become apostates to a perceived return of China’s bull market, I recently pointed out in a tweet that... (Figure 2)

"While previous episodes of government stimulus did bolster valuations, they turned out to be short-lived, highly volatile, and resulted in diminishing returns for #SSE levels. The 2016 & 2020 support had little impact on its bear market. Will history rhyme?"

Or whatever boom that took place before tended to morph into a bust. Even worse, the subsequent stimulus produced diminishing returns with the lower levels of the Shanghai Composite Index (SSE).

In other words, monetary inflation or stimulus from credit expansion must be applied at a much larger scale than before to magnify the effects of a boom.

As the great Dean of Austrian economics, Murray Rothbard, once warned

Like the repeated doping of a horse, the boom is kept on its way and ahead of its inevitable comeuppance by repeated and accelerating doses of the stimulant of bank credit. It is only when bank credit expansion must finally stop or sharply slow down, either because the banks are getting shaky or because the public is getting restive at the continuing inflation, that retribution finally catches up with the boom. (Rothbard, 2015)

China’s experience has somewhat resonated with the Philippines.

Figure 3

It took a combination of historic rate cuts, massive reductions in reserve requirements, unprecedented relief measures, and direct injections by the BSP into the banking system via the expansion of its balance sheet to rescue the Philippine PSEi 30 in 2020. (Figure 3, upper image)

The PSEi 30 peaked in 2022 along with the cresting of the BSP's assets.

It is also not a coincidence that the PSEi has wilted in the face of the slow-motion erosion of the BSP’s balance sheet, which was eventually reversed in 2023.

The BSP’s U-turn put a floor under the PSEi 30 and rebooted the current rally.

One can probably thank Other Financial Institutions (OFCs) for representing part of the National Team supporting the PSEi 30.

The BSP has been rebuilding its asset base, this time from external borrowings by the National Government and the banking system.

III. Market Concentration and Unimpressive Volume and Breadth, Rampaging Philippine Bank Shares and the Lehman-Bear Stearns Experience

Of course, the difference between the bull market of 2009-2013 and today is that the PSEi 30 run has barely been supported by volume and breadth.

Main board volume remains substantially below the level reached at even lower PSEi 30 levels in 2022. (Figure 3, lower graph)

Because of this obsession with pumping the index to portray a bull market, the "national team" has concentrated its aggressive stock-pumping activities on the top heavyweights.

As a result, the market capitalization share of the top five companies reached 51.1% last October 4, following a record 51.92% last April.

Figure 4

Furthermore, because RRR cuts and BSP rate cuts were sold to the public as policies that would accomplish economic nirvana, the Financial/Banking Index roared, with year-to-date returns spiking 37.7% and its index soaring to a record high! (Figure 4, upper chart)

Astoundingly, shares of China Bank [PSE:CBC] have spiraled in ways echoing Bitcoin, GameStop [NYSE:GME], and Nvidia [Nasdaq:NVDA]! (Figure 4, lower pane)

CBC posted 91.3% year-to-date returns, with much of that accomplished in the last four weeks!

Figure 5

If history tells us anything, bank share prices going berserk could mean anything other than economic or financial prosperity. The experiences of Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns provide examples: their share prices sprinted to an all-time high before collapsing, heralding the Great Financial Crisis (2007-2008). (Figure 5, topmost chart)

To be clear, we aren’t suggesting that CBC and other record-setting bank shares, such as BPI, are a simulacrum of Lehman; rather, we are pointing to the distortive behavior of speculative derbies that may hide impending problems in the sector.

Of course, foreign buying did provide support to the national team. For the first time since 2019, the PSE posted net inflows of Php 108 million in the first nine months of 2024. (Figure 5, middle graph)

Meanwhile, in the PSE, the cumulative market share of the PSEi 30’s best-performing ICT and the three PSEi 30 banks has reached 32.73%, which is closing in on August's record of 33.14%.

IV. Retail Players Emerge

However, signs indicate that the retail segment appears to be jumping on board the developing mania, which has been marketed as another version of the "return of the bull market."

Though still negative, 2024’s nine-month breadth has had the best showing since 2017. (Figure 5, lowest image)

Figure 6

Furthermore, the declining share of the top 10 brokers relative to the MBV could be another contributing factor. It was 60.4% in the week of October 4th, down from a recent high of over 65%. (Figure 6 upper visual)

Major brokers could utilize 'done-through' trades or outsource trades with partner brokers to conceal or dilute this number.

Despite the paucity of volume, the trading share of the top 20 most-traded issues has dropped to about 80% for the fourth consecutive week from the previous range of 84-86%. (Figure 6, lower diagram)

Figure 7

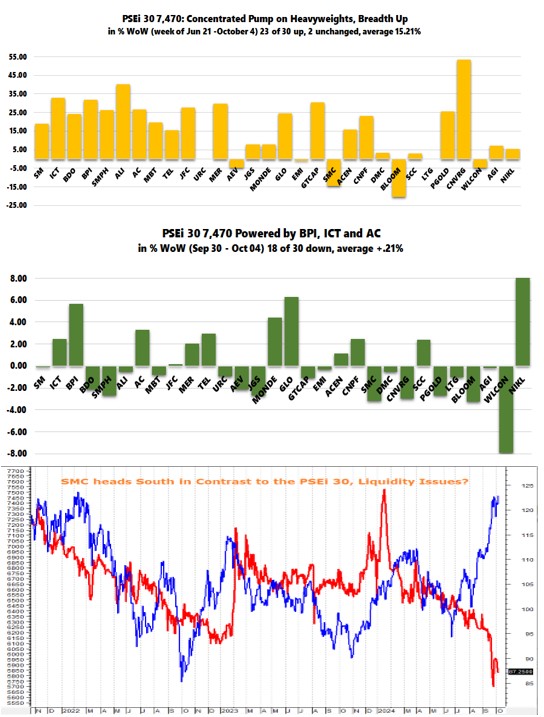

Since the low on June 21st, the returns of the top 10 heavyweights delivered the bulk of the gains for the PSEi 30. While 23 issues closed higher, 2 remained unchanged, and 5 declined. The average return of the top 5 was 26.84%, while the average return for the top 10 was 26.4% (Figure 7, topmost graph)

Breadth was largely incongruent with this week’s 0.53% returns, 83% of which were attributable to Friday’s pre-closing pump. Although 18 of the composite PSEi 30 issues closed down, the upside volatility allowed for a positive weekly return of 0.21% (Figure 7, middle image)

V. Why the Opposite Direction of San Miguel’s Share Prices? Conclusion

Finally, SMC share prices continue to move diametrically opposite to the sizzling hot PSEi 30. (Figure 7, lowest graph)

What gives? Will SMC’s debt breach the Php 1.5 trillion barrier in Q3?

Have SMC’s larger shareholders been pricing in developing liquidity concerns? If so, why are bank shares skyrocketing, when some of them are SMC’s biggest creditors?

Bottom line: The levels reached by the PSEi 30 and its outsized returns attained over a few months barely support general market activities, which remain heavily concentrated on the actions of the national team and volatile foreign fund flows.

Instead, the present melt-up represents an onrush of speculative fervor driven by the BSP’s stealth liquidity easing measures, even before their rate cut. Moreover, real economic activities hardly support this melt-up.

___

reference

Murray N. Rothbard, Why the Recurring Economic Crises?, August 27, 2015, Mises.org