A good running example of the principal-agent or the agency problem in play has been the unravelling controversy over Warren Buffett’s supposed “would be” successor-David Sokol.

David Sokol recently resigned from Berkshire Hathaway following allegations of unethical practice.

According to Steve Shaefer of Forbes,

Berkshire Hathaway executive David Sokol, who served as chairman of MidAmerican Holding Company and Johns Manville as well as Chairman and CEO of NetJets, resigned from the company in a letter to Warren Buffett Monday.

Buffett announced his departure in a press release Wednesday, which also noted that Sokol owned shares in Lubrizol, a company Berkshire recently agreed to acquire for some $9 billion. The departure of Sokol comes as a shock to Berkshire watchers who figured the executive was one of the potential successors for Buffett.

In the announcement, Buffett stressed that he and Sokol do not feel there was anything illegal in his trades of Lubrizol shares.

Although both David Sokol and Warren Buffett via Berkshire Hathaway denied that this has been the cause of his resignation, media has been all over what has been perceived as ethical impropriety.

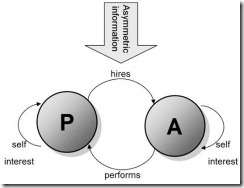

The Sokol affair simply highlights what we have been talking about as the conflict of interests by participating agents—based not only from asymmetric information but from asymmetric interests or incentives that drives people’s actions.

Principal Agent Problem Diagram from Wikipedia.org

Mr. Sokol, who acquired shares of Lubrizol before pitching it to his boss, Mr. Buffett, saw nothing wrong with this. In fact, in a CNBC interview Mr. Sokol cites Mr. Charles Munger, Mr. Buffett’s close friend and vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway of doing the same.

“I don’t believe I did anything wrong. Charlie Munger owned 3% of BYD before he asked me to go look at it.” [dawnwires.com]

In the stock market, when agents or brokers pre-empt their clients by taking positions for his/her account, in the expectations that the clients orders could affect the price movements of specific stocks, is known as “frontrunning” (investopedia.com) an illegal practise that is punishable by law.

Although Mr. Sokol’s case hardly resembles frontrunning, because he bought the shares before he offered it to Mr. Buffett, this goes to show how such practices has punctured on the current laws.

Notes Mr. Jason Zweig at the Wall Street Journal, (bold emphasis mine)

Mr. Sokol's trading falls under what Stephen Bainbridge, an expert on securities at the UCLA School of Law, calls "an enormously gray area of the law." It also is a reminder that a basic principle of securities law—disclosure cures conflicts—is nonsense.

"Even assuming that [Mr. Sokol] did nothing illegal, [his action] is typical of the kinds of conflicts of interest permitted by our financial system that undermine the integrity of markets," says Max Bazerman, an ethicist at Harvard Business School and co-author of the new book "Blind Spots."

Most people have what Mr. Bazerman calls an ethical blind spot. Faced with a potential conflict of interest, you automatically conclude that it couldn't possibly offer any temptation to someone of superior character—like you or those closest to you.

While I agree that this seems like an issue of ‘ethical blind spots’, I don’t share the impression that “conflicts of interest permitted by our financial system that undermine the integrity of markets” or of the insinuation that ‘ethical’ laws are needed to keep the “integrity of markets”. That would be misstating the case.

And that’s because it is the nature of people to be guided by self-interest based on the individual’s distinctive value preferences or priorities. And people’s diversified self interests always conflict with each other, but still could represent benefits for all the concerned, though not equally.(This is the essence of trade)

What has actually undermined the financial system is the conflict of interest (agency problem) between the political agents along with their regulatory patrons and their economic clients. Regulatory arbitrages, regulatory capture, revolving door politics, bailouts to name a few, has been significant contributors to the political-economic inequality.

And as one can see from the above account, current disclosure laws can’t stop people from circumventing them.

Besides, if Mr. Sokol’s allegation of Mr. Munger is accurate, then Mr. Buffett has been obviously tolerant of such practice.

To see why, Mr. Buffett probably sees this as a way to reward his underlings, who by diligent scrutiny over the target companies, takes on risks directly to emphasize their vote of confidence. It’s not even sure that what the underlings buy will be bought by Mr. Buffett.

As Mr. Buffett stressed on Berkshire’s recent press release,

Dave’s purchases were made before he had discussed Lubrizol with me and with no knowledge of how I might react to his idea. In addition, of course, he did not know what Lubrizol’s reaction would be if I developed an interest. (bold emphasis mine)

Thus such actions represent risks borne solely by both Mr. Munger and Mr. Sokol.

Perhaps, for Mr. Buffett this could have signified as parallel to a finder’s fee, that’s if he ever agrees with their investment concept.

This also highlights on the differences of what is seen as an ethical issue. What may seem wrong to the others may seem right to Mr. Buffett (although I would assume that he would distance himself from this controversy)

I think the editorial of Financial Times captures this well, (bold highlights mine)

That Mr Sokol has left to build his own investment portfolio is more than unintentionally ironic. The whole affair highlights Berkshire’s informal style of operation. This is possible because of the high degree of confidence reposed in the company by investors. Mr Buffett and his team can scour the world for opportunities untrammelled by investment mandates and other bureaucratic restraints.

The licence exists, of course, because of Mr Buffett’s superior investment record. He has beaten the stock market indices by a broad margin since the mid-1960s. But it will be harder for Berkshire to continue outperforming given its now-vast size, as even Mr Buffett has admitted. This should give investors pause. The risk of executives abusing informal processes is greatest at times when operational performance is under pressure.

In short, this hasn’t been an issue to Berkshire’s investors because of the rewards these investors have been showered with over these years. It would all be a different story if Berkshire lost money or has underperformed.

The other point is that people should be self-vigilant over their investments in the knowledge that there will always be conflict of interest issues at hand.

To rely on government to resolve ethical issues will only bring about dependency, complacency, and equally, conflict of interest issues but not between private agents but among public and private agents, which should even complicate and worsen the case, as manifested during the last crisis. In other words, more problems will arise from regulations meant to address ethical issues.

The market mechanism for discipline enforced by such perceived misconduct is social stigma or ostracism or reputational risk.

Finally, the public trial faced by Berkshire Hathaway and Mr. Sokol simply highlights of the uniqueness of Mr. Buffett’s management style.

Once Mr. Buffett goes, perhaps Berkshire would most likely lose its magic. All these seem ominous with Moody’s projecting the “Sokol affair” as negative for Berkshire’s credit rating standings (Reuters).

Berkshire’s Corporate Structure and Investment Holdings From theofficialboard.com

Still yet, the complexity of Warren Buffett’s flagship Berkshire Hathaway’s organizational structure operating on her vast investment holdings also underscores the FT’s editorial observations of Berkshire at “now-vast size” or perhaps reaching its growth limit.

And that’s why I have argued here that Mr. Buffett has resorted to political entrepreneurship perhaps out of the desperation to maintain public’s high expectations from a Warren Buffett managed Berkshire.

Bottom line: the principal-agent problem is an inherent feature of the marketplace, which has been immensely underappreciated but must be understood by all.

1 comment:

Thank you for this analysis - perhaps the most thoughtful, insightful I have seen on the Buffett/Sokol controversy. The "finder's fee" interpretation is particularly sharp.

But consider a slightly different perspective on Berkshire's purchases of companies in which executives have an interest: Pre-screening of investment ideas. Most all of Berkshire's executives are independently wealthy. Munger, Sokol, and many others sold their companies to Berkshire. A few received stock, but most took a check. So they have significant funds, outside of their Berkshire stock - Buffett, Sokol, Munger, and several others each have a billion dollars or more to invest in their spare time.

So Munger invests A LOT of money in a variety of companies he thinks are good. Some may be appropriate for the company to buy, many are not. Presumably Munger thought BYD was a good deal, but Buffett initially did not. Charlie put his money where his mouth was, and eventually Warren was convinced. Presumably this took place over months or years. Conflict? Agency problem? Maybe, but this is minor, and Warren in a big boy, and makes decisions for himself. Generally any "finders fee" investment profits will be small.

So Sokol says to Buffett, "heres an idea for a company, I own some shares" - nothing new there, Buffett says "I'll pass, because XXX in their financials looks shaky". So far, so good. But - "I bought the stock last week"? or " I met with their CEO after we spoke, and here is what they have to say about XXX"? This fails the smell test, and Sokol knew it.

As Buffett wrote to his managers: “The priority is that all of us continue to zealously guard Berkshire’s reputation. We can’t be perfect but we can try to be. As I’ve said in these memos for more than 25 years: We can afford to lose money – even a lot of money. But we can’t afford to lose reputation – even a shred of reputation.”

Ooops!

Post a Comment