At a CNN interview, US President Obama crony Warren Buffett denies a bubble in US stocks: Buffett said stocks "might be a little on the high side now, but they've not gone into bubble territory."

Yet he further stated that: "I don't find cheap stocks to buy either," he said, adding after follow-up questions that there were "very little" and "very few" bargains out there right now.

For Mr. Buffett, the framing of bubble in the context of portfolio management matters.

In Berkshire’s 2014 annual report, Mr. Buffett wrote: (bold mine)

There is an important message for investors in that disparate performance between stocks and dollars. Think back to our 2011 annual report, in which we defined investing as “the transfer to others of purchasing power now with the reasoned expectation of receiving more purchasing power – after taxes have been paid on nominal gains – in the future.”The unconventional, but inescapable, conclusion to be drawn from the past fifty years is that it has been far safer to invest in a diversified collection of American businesses than to invest in securities – Treasuries, for example – whose values have been tied to American currency. That was also true in the preceding half-century, a period including the Great Depression and two world wars. Investors should heed this history. To one degree or another it is almost certain to be repeated during the next century.Stock prices will always be far more volatile than cash-equivalent holdings. Over the long term, however, currency-denominated instruments are riskier investments – far riskier investments – than widely-diversified stock portfolios that are bought over time and that are owned in a manner invoking only token fees and commissions. That lesson has not customarily been taught in business schools, where volatility is almost universally used as a proxy for risk. Though this pedagogic assumption makes for easy teaching, it is dead wrong: Volatility is far from synonymous with risk. Popular formulas that equate the two terms lead students, investors and CEOs astray.It is true, of course, that owning equities for a day or a week or a year is far riskier (in both nominal and purchasing-power terms) than leaving funds in cash-equivalents. That is relevant to certain investors – say, investment banks – whose viability can be threatened by declines in asset prices and which might be forced to sell securities during depressed markets. Additionally, any party that might have meaningful near-term needs for funds should keep appropriate sums in Treasuries or insured bank deposits.For the great majority of investors, however, who can – and should – invest with a multi-decade horizon, quotational declines are unimportant. Their focus should remain fixed on attaining significant gains in purchasing power over their investing lifetime. For them, a diversified equity portfolio, bought over time, will prove far less risky than dollar-based securities

Yet action speak louder than words.

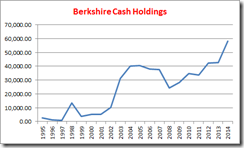

Berkshire Cash and Cash Equivalents since 1995

Berkshire cash at US$ 60.98 billion or 17% of market cap as of yesterday (based on Yahoo Finance).

The cash holdings of Mr. Buffett’s flagship Berkshire Hathaway has been skyrocketing.

From an annualized basis, Berkshire’s biggest gain in cash equivalent has been in 2014. Yet since 2008, Berkshire has been stockpiling cash reserves.

And the crux has been, Berkshire has done little to use those cash hoard!

While it may be true that “a multi-decade horizon, quotational declines are unimportant”, buying at a elevated prices will have an impact on portfolio returns even at the long run.

And what Mr. Buffett didn’t say has been that most of Berkshire’s holdings has been from long term positions, rather than from current investments.

It’s true that Berkshire Hathaway recently bought $560 million in the automotive sector through Axalta Coating System, a 145-year old seller of coatings for cars, SUV’s and commercial vehicles, but this hardly signifies a dent on the $60 billion stash.

At least Mr. Buffett has been candid to admit that he is just human and has been subject to miscalculations and losses.

In the same annual report he shares the sad experience of Berkshire’s position with Tesco.

Attentive readers will notice that Tesco, which last year appeared in the list of our largest common stock investments, is now absent. An attentive investor, I’m embarrassed to report, would have sold Tesco shares earlier. I made a big mistake with this investment by dawdling.At the end of 2012 we owned 415 million shares of Tesco, then and now the leading food retailer in the U.K. and an important grocer in other countries as well. Our cost for this investment was $2.3 billion, and the market value was a similar amount.In 2013, I soured somewhat on the company’s then-management and sold 114 million shares, realizing a profit of $43 million. My leisurely pace in making sales would prove expensive. Charlie calls this sort of behavior “thumb-sucking.” (Considering what my delay cost us, he is being kind.)During 2014, Tesco’s problems worsened by the month. The company’s market share fell, its margins contracted and accounting problems surfaced. In the world of business, bad news often surfaces serially: You see a cockroach in your kitchen; as the days go by, you meet his relatives.We sold Tesco shares throughout the year and are now out of the position. (The company, we should mention, has hired new management, and we wish them well.) Our after-tax loss from this investment was $444 million, about 1/5 of 1% of Berkshire’s net worth. In the past 50 years, we have only once realized an investment loss that at the time of sale cost us 2% of our net worth. Twice, we experienced 1% losses. All three of these losses occurred in the 1974-1975 period, when we sold stocks that were very cheap in order to buy others we believed to be even cheaper

Finally, yet some very useful advise from the annual report (bold italics mine)

If the investor, instead, fears price volatility, erroneously viewing it as a measure of risk, he may, ironically, end up doing some very risky things. Recall, if you will, the pundits who six years ago bemoaned falling stock prices and advised investing in “safe” Treasury bills or bank certificates of deposit. People who heeded this sermon are now earning a pittance on sums they had previously expected would finance a pleasant retirement. (The S&P 500 was then below 700; now it is about 2,100.) If not for their fear of meaningless price volatility, these investors could have assured themselves of a good income for life by simply buying a very low-cost index fund whose dividends would trend upward over the years and whose principal would grow as well (with many ups and downs, to be sure).Investors, of course, can, by their own behavior, make stock ownership highly risky. And many do. Active trading, attempts to “time” market movements, inadequate diversification, the payment of high and unnecessary fees to managers and advisors, and the use of borrowed money can destroy the decent returns that a life-long owner of equities would otherwise enjoy. Indeed, borrowed money has no place in the investor’s tool kit: Anything can happen anytime in markets. And no advisor, economist, or TV commentator – and definitely not Charlie nor I – can tell you when chaos will occur. Market forecasters will fill your ear but will never fill your wallet.The commission of the investment sins listed above is not limited to “the little guy.” Huge institutional investors, viewed as a group, have long underperformed the unsophisticated index-fund investor who simply sits tight for decades. A major reason has been fees: Many institutions pay substantial sums to consultants who, in turn, recommend high-fee managers. And that is a fool’s game

Well, the above insight brings us back to Mr. Buffett’s old adage: 'You want to be greedy when others are fearful. You want to be fearful when others are greedy. It's that simple.'

So there you have it, for Mr. Buffett the term "bubble" seems as a political sensitive word. So he fudges this by framing the market over the long term versus the short term.

Updated to add: Of course uttering the word 'bubble' may just deflate Mr. Buffett's glory, prestige and esteem, as the investing public would refrain from pushing up Berkshire Hathaway or assets held by Berkshire.

Updated to add: Of course uttering the word 'bubble' may just deflate Mr. Buffett's glory, prestige and esteem, as the investing public would refrain from pushing up Berkshire Hathaway or assets held by Berkshire.

Yet in his 2014 annual report Mr. Buffett made lots of caveats in citing "borrowing has no place in the investor's tool kit" when US non-financial companies has been in a borrowing splurge, that makes markets susceptible to "anything can happen anytime in the markets".

And if one looks at Mr. Buffett's Berkshire’s Hathaway cash stash, they seemed positioned for a coming fat pitch…

So do as I say, not as I do.

No comments:

Post a Comment