``But the law is made, generally, by one man, or by one class of men. And as law cannot exist without the sanction and the support of a preponderant force, it must finally place this force in the hands of those who legislate. This inevitable phenomenon, combined with the fatal tendency that, we have said, exists in the heart of man, explains the almost universal perversion of law. It is easy to conceive that, instead of being a check upon injustice, it becomes its most invincible instrument.” Frédéric Bastiat, The Law

Yo-yo Markets And The Financial Reform Bill

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, hedge fund manager and author Andy Kessler seems right; the actions of the US markets, which directly affects other financial markets, will be in a state of a Yo-yo for as long as the US government continually intervenes to suppress market forces from revealing its true conditions.

Mr. Kessler writes[1],

``Call it the yo-yo market—from the top of the wall to the bottom of the pit and back—and you better get used to it. It's hard to tell which market moves are real and based on prospects for better profits, as opposed to moves that are driven by all the extraordinary government measures to prop up the world economy. Until a few things are resolved, you'd better learn the yo-yo sleeper trick—that is, keep spinning at the bottom without going up.”

Mr. Kessler appears to echo what we’ve been saying all along[2]---that politics has and will shape the outcome of the markets.

Mr. Kessler cites the pervasive impact of the Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP), the assorted “crutches” or the guarantees, stimulus packages, and money printing, and importantly, the impact of the changes in the regulatory environment.

Since we had exhaustively discussed on the first two factors, in the light of the passage of the Financial Reform Bill[3], we’d tackle more on the aspects of the regulatory environment.

After having a rather promising start for the week, the US markets fell hard Friday after the ratification Financial Reform Bill. The losses virtually expunged on the early gains made whereby the net weekly result for the US S&P 500 had been a net loss of 1.21% (see figure 1).

Figure 1: US Global Investors[4]: Sectoral Performance

Nevertheless the degree of losses had been uneven, where some sectors of the S&P 500 have managed to escape the clutches of the selling pressures, such as the Consumer staples and the Technology sector.

True, correlation doesn’t automatically translate to causation. The Financial Reform bill may or may not have directly affected Friday’s performance.

However, given that the largest victim of the selloff had been in the financial sector, which is the target of the slew of new regulations, then I must argue that there could have been a substantial connection in the way the markets perceive how these purported reforms would affect the industry.

In other words, markets may have seen more downside risks to the industry, as a result of the law, and these perceptions have filtered into the other sectors.

Yet it’s simply amazing how some mainstream analysts fail to acknowledge of the vital role played by the regulatory environment in shaping the allocation of resources.

They seem to think that investment is merely consequence of waking up on a particular side of the bed which determines their “animal spirits”, or that, confidence is simplistically established as a function of random temperaments or moods—and largely detached from the coordination of consumers and producers in the marketplace.

Thus, many make specious arguments that new regulations won’t affect the business operations.

Importantly, the same experts fail to take into account that entrepreneurs invest with the aim to profit from providing or servicing the needs or desires of the consumers. Thus, a material change in the regulatory environment may affect the fundamental profit and loss equation. And the ensuing changes could also alter the feasibility of the operations of any enterprises, to the point which could lead to either closures, or impair the business operations. The net effect should be more losses and rising unemployment.

In short, business confidence is a function, not of some mood swings, but of property rights. Likewise confidence relative to investment should be predicated not just with the return ON capital, but with the return OF capital.

Regime Uncertainty From Arbitrary Laws

Economist Robert Higgs calls this reduced confidence factor as “regime uncertainty” where he argues[5] (bold emphasis mine)

``To narrow the concept of business confidence, I adopt the interpretation that businesspeople may be more or less “uncertain about the regime,” by which I mean, distressed that investors’ private property rights in their capital and the income it yields will be attenuated further by government action. Such attenuations can arise from many sources, ranging from simple tax-rate increases to the imposition of new kinds of taxes to outright confiscation of private property. Many intermediate threats can arise from various sorts of regulation, for instance, of securities markets, labor markets, and product markets. In any event, the security of private property rights rests not so much on the letter of the law as on the character of the government that enforces, or threatens, presumptive rights.”

Thus, to allege that new regulations will hardly be a factor in the investment environment would redound to utter detachment with reality.

Well, what can we expect from so-called ivory tower “experts” who seem to think that they own the monopoly of knowledge, via mathematical models and aggregates, when their sources of income depends on wages than from wagering on the dynamic trends of the marketplace? (Pardon me for the ad hominem, but perspectives are mostly shaped by interests)

Take the Great Depression (GD) of 1930s, which many prominent bears have anchored their projections as the probable direction of today’s market.

From the monetarist viewpoint, the GD had been all about monetary contraction, whereas from the Keynesian perspective this had been about falling aggregate demand. Both of which has been diagnosed by the incumbent Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke[6] as the major causes from which current policies have been designed to address. Yes—the solution? The printing press!

While both did have a role to play, the oversimplistic account of the GD fails to incorporate the havoc generated by the legion of intrusive laws enacted by the US government’s New Deal program, aimed at keeping prices at status quo ante or from adjusting to the realities of the unsustainable misdirection of capital from the inflation boom induced depression. These policies, which threatened property rights, had greatly exacerbated and prolonged the grim conditions then.

These laws included[7]:

1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act, National Industrial Recovery Act, Emergency Banking Relief Act, Banking Act of 1933 Act, Federal Securities Act, Tennessee Valley Authority Act, Gold Repeal Joint Resolution, Farm Credit Act, Emergency Railroad Transport Act, Emergency Farm Mortgage Act National Housing Act, Home Owners Loan Corporation Act

1934 Securities Exchange Act, Gold Reserve Act, Communications Act, Railway Labor Act

1935 Investment Company Act, Revenue Act of 1940, Bituminous Coal Stabilization Act, Connally (“hot oil”) Act, Revenue Act of 1935, National Labor Relations Act, Social Security Act, Public Utilities Holding Company Act, Banking Act of 1935, Emergency Relief Appropriations Act, Farm Mortgage Moratorium Act

1936 Soil Conservation & Domestic Allotment Act, Federal Anti-Price Discrimination, Revenue Act of 1936

1937 Bituminous Coal Act, Revenue Act of 1937, Act Enabling (Miller-Tydings) Act

1938 Agricultural Adjustment Act, Fair Labor Standards Act, Civil Aeronautics Act, Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act

1939 Administrative Reorganization Act

1940, Second Revenue Act of 1940

Figure 2: Wikipedia.org[8]: US Income Tax (left window), Higgs: Government Purchases (Current$) and Gross Private Investment (Current$) Relative to Gross Domestic Product (Current$), 1929–1950

For instance, one should also take into account how the surge in taxation (left window) to fund the explosion in government expenditures during the Great Depression (right window) contributed to stymie investments or production (see figure 2)

As Henry Hazlitt aptly described how taxes affect investment or production[9]

``When the total tax burden grows beyond a bearable size, the problem of devising taxes that will not discourage and disrupt production becomes insoluble.”

In other words, when the expectations for profits are reduced, borne out of the expectations of higher taxes or from other regulatory interdictions which places property rights at risks, then investments will obviously follow—and decline.

Therefore the regulatory and tax regime functions as crucial factors to the conditions of confidence in the marketplace.

Paradoxically, one function of the law is the avoidance of this “regime uncertainty”. But when the state is unclear about the direction of policies and regulation, the “means” can contradict the “end”. So, instead of stability, such laws could engender or promote “regime uncertainty”. Yet, these are commonplace feature of many arbitrary laws.

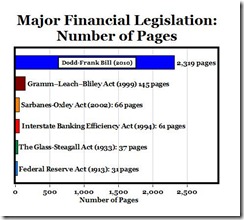

Take the recently enacted Financial Reform Bill, it has been reported to contain 2,319 pages (see figure 2)

Figure 2: Mark Perry[10]: Major Financial Legislation: Number of Pages

The sheer mountain of pages by itself would make the reformist law seem like a regulatory quagmire and appears appallingly political relative to the enforcement issues.

Heritage’s Conn Carroll explains[11],

``With the single stroke of a pen, President Barack Obama signed the Dodd-Frank financial regulation bill that set in motion 243 new formal rule-makings by 11 different federal agencies. Each of the 243 rule-makings will employ hundreds of banking lobbyists as they try to shape what the final actual laws will look like. And when the rules are finally written, thousands of lawyers will bill millions of hours as the richest incumbent financial firms that caused the last crisis figure out how to game the new system.”

The implication is that where financial firms compete, not to please customers, but to gain the favour of regulators, this essentially represents as the hallmarks of corporatism or crony capitalism.

Thus, the financial reform bill is likely to foster political privileges which entrenches the “too big too fail” institutions, who will profit from economic rent.

The litany of adverse effects from such ambiguous bill will be one of expanded corruption, lack of credit access for consumers, reduced consumers protection (in contrast to the purported letter of the law), regulatory capture, regulatory arbitrages, higher risks to taxpayers on greater risk appetite for the politically privileged firms (moral hazard issue), increased red tape via an expanded bureaucracy, higher compliance costs, more government spending and reduced competition which overall translates to broad based economic inefficiencies.

Yet the reformist law is also said not only to be opaque, but gives undue confiscatory power based on the whims of regulators.

Mr. Kessler writes[12], ``What is even more troubling is the prospect of government seizures built into the Dodd-Frank financial bill. This is much like the seizure of property from auto industry bond holders (denounced as speculators) in the bankruptcy of GM and Chrysler.

``Dodd-Frank also provides government leeway to seize firms it considers a systemic risk, without really defining what that systemic risk is. Why anyone would provide debt to large financial institutions (or auto makers) is beyond me, certainly not without demanding a huge premium for the seizure risk. The cost of capital for the U.S. economy is sure to rise, slowing growth.”

This means that Financial Reform bill also entails that the political favoured institutions are likely to become veiled instruments for political agenda of those in power.

And laws of this nature is what Frédéric Bastiat long admonished[13],

``But, generally, the law is made by one man or one class of men. And since law cannot operate without the sanction and support of a dominating force, this force must be entrusted to those who make the laws.

``This fact, combined with the fatal tendency that exists in the heart of man to satisfy his wants with the least possible effort, explains the almost universal perversion of the law. Thus it is easy to understand how law, instead of checking injustice, becomes the invincible weapon of injustice. It is easy. to understand why the law is used by the legislator to destroy in varying degrees among the rest of the people, their personal independence by slavery, their liberty by oppression, and their property by plunder. This is done for the benefit of the person who makes the law, and in proportion to the power that he holds.”

In short, arbitrary laws, as the Financial Reform bill, can function as instruments of injustice.

Thus, it is NOT impractical or improbable to argue that in the wake of the enactment of the Financial Reform Bill, the ambiguity and arbitrariness of the law and the increased politicization of the financial industry would likely result to greater perception of risks which may be reflected on the “Yo-yo” actions or a more volatile US markets.

At the end of the day, regulatory obstacles will likely compel capital to look for a capital friendly environment from which to flourish.

[1] Kessler, Andy, The Yo-Yo Market and You, Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2010

[2] See How Political Tea Leaves Will Shape The Investment Landscape

[3] Bloomberg, U.S. Congress Passes Wall Street Regulation Bill, July 15, 2010

[4] US Global Investors, Investor Alert, July 16, 2010

[5] Higgs, Robert Regime Uncertainty, Why the Great Depression Lasted So Long and Why Prosperity Resumed after the War

[6] Bernanke, Ben Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here, Speech Before the National Economists Club, Washington, D.C. November 21, 2002

[7] Higgs, Ibid

[8] Wikipedia.org, Income tax in the United States

[9] Hazlitt, Henry Taxes Discourage Production, Chapter 5 Economics In One Lesson

[10] Perry, Mark ‘I Didn’t Have Time to Write a Short Bill, So I Wrote a Long One Instead,’ Part II The Enterprise Blog July 16

[11] Carroll, Conn Morning Bell: The Lawyers and Lobbyists Full Employment Act, Heritage Blog, July 16, 2010

[12] Kessler, Andy Ibid.