The twin result of the Federal Reserve’s increase in the money supply, which pushes interest rates below that market-balancing point, is an emerging price inflation and an initial investment boom, both of which are unsustainable in the long run. Price inflation is unsustainable because it inescapably reduces the value of the money in everyone’s pockets, and threatens over time to undermine trust in the monetary system. The boom is unsustainable because the imbalance between savings and investment will eventually necessitate a market correction when it is discovered that the resources available are not enough to produce all the consumer goods people want to buy, as well as all the investment projects borrowers have begun. The unsustainability of such a monetary-induced investment boom has been shown, once again, to be true in the latest business cycle.-Richard Ebeling

Libya’s civil war, the ongoing MENA People Power revolts, $100 oil and record food prices, recent credit downgrades of Greece and Spain[1], and just the other day, the 1-2 punch (earthquake-tsunami) disaster that slammed on Japan have all been buffeting on the markets which gives some good and noteworthy pitches to be on the bearish camp.

But one has to distinguish between noise and signal. Noises tend to have short term effects while signals tend to underpin the market’s fundamental drivers.

Noise and Signals

Are the above events representatives of as noise or as signals?

If one looks at the broad performances of the global financial markets, what you read in the news isn’t exactly the sentiments that appear as being ventilated on the markets; whether it is the global stock markets, commodity, currency or bond markets.

True, markets have been showing some indications of volatility but this does not automatically mean that they account for as evidence of signals.

In other words, media sentiment and the voting public represented by the market actions don’t seem to match.

Figure 1 Bloomberg: ASEAN Equities

ASEAN bourses seem to be good examples of demolishing misguided popular wisdom.

The year-to-date chart of the major ASEAN equity bellwethers-Malaysia KLSE (yellow), Philippine Phisix (green), Indonesia (JCI), and Thailand’s SET (SET) shows of a consolidation phase.

Yet the actions of the last three (Phisix, JCI and the SET) seems to parallel what you can see in an Olympic sporting event known as synchronized “swimming”. In short, ASEAN bourses have manifested strong or tight correlations.

Let me add that such tight correlations do not represent causation nor are they designed or engineered actions. The point is that certain underlying forces have been prompting market participants to act spontaneously but almost in the same manner.

The mainstream has lately been saying that the weakness of ASEAN markets reflected on high oil prices and the spreading unrest in the Middle East. Yet ASEAN markets have began to reverse to the upside even as Oil peaked (at $107.34 on March 7th) and as MENA events has seemingly worsened, validating my argument that the mainstream tend to fixate on the available information[2] rather than indulge in critical analysis.

Yet in reflecting on the actions of the Philippine Phisix:

-where foreign trade has accounted for only 40.69% of overall trade (accrued year to date basis)

-where foreign trade has registered a substantial net negative figure year to date (6.3 billion pesos or about USD $144 million @43.65), and

-where the Peso has slightly firmed from the start of the year (43.84 at the close of 2010), and 43.65 last Friday

I can see a paradox—a strong Peso and equity outflows—or a meaningful divergence.

A side note: the bulk of the foreign selloff came in January but this has signficantly turned positive last week (1.954 billion pesos or USD $44.8 million @43.65).

What we can glean from these:

-local investors have been providing the crucial support to the markets during the past 2 months

- importantly, even as foreign trade in equity markets accounted for a negative, overall portfolio flows as reported by the BSP revealed a positive figure $428 million for January or a net $193 million[3]. These figures are lower than the past, but nonetheless STILL positive.

These variables appear to imply that the negative foreign trade in the PSE had NOT been repatriated abroad, but possibly rotated into other local assets.

And this perhaps explains the continued strenght of the Peso despite a weak equity market environment. Again, a divergence that is likely to be resolved soon.

Rotation To Property Sector and A Booming Credit Environment

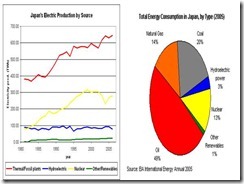

Figure 2: IMF[4]: Philippine Real Estate Market

Further observation tells us that the local equity market rally over the past 2 weeks had been spearheaded by the property sector (+9.7% in 2 weeks) which could highlight on such rotational dynamics.

The actions in the local property market seem to have mirrored on the actions of the Philippine Stock Exchange (see figure 2).

The local property sector appears to be bottoming out (left window) following a short bout of credit boost during the climax of the global crisis in 2008. I am not sure why such boost has occurred, but I would suspect that this could be part of a government related stimulus spending.

But today, with a recovering credit environment emerging from the artificially suppressed interest rates, it isn’t far fetched to the suggest that long range capital intensive projects will be the principal beneficiaries of low interest rate regime. And it is why I see an imminent property boom here[5] if not in Asia.

And ASEAN property prices likewise appear to be recovering from the 2008 contagion (right window).

And speaking of the domestic credit enrivonment, many aspects seem to playout exactly as the Austrians have seen it through their Austrian Business Cycle Theory...

Credit growth has expanded to a 21 month high[6] from which the Manila Bulletin breaksdown the details[7] as,

Of the total, production loans, which account for more than four-fifth of commercial banks’ (KBs) loan portfolio expanded year-on-year by 12.4 percent over last December’s 10.1 percent.

The growth of consumer loans was almost steady at 8.7 percent, the BSP said.

The central bank traced the strong growth in production loans to higher lending extended to the manufacturing, which rose by 26.7 percent; electricity, gas and water, 21.3 percent; real estate, renting and business services, 17.7 percent; wholesale and retail trade, 14.2 percent; and agriculture, hunting and forestry, 6.4 percent.

Loans extended to construction sector also grew but at a slower pace of 7.8 percent compared to the 15.6 percent last December.

On the other hand, negative growth was registered in lending to financial intermediation at -5.7 percent and education at -13.1 percent.”

All these credit activities, mainly interpreted as demand based economic growth, will likely continue to energize the domestic financial markets, as well as, stoke consumer price inflation hidden from the eyes of the public[8].

As Friedrich von Hayek once wrote of the Austrian Business cycle[9]. (bold emphasis mine)

Now the chief effect of inflation which makes it at first generally welcome to business is precisely that prices of products turn out to be higher in general than foreseen. It is this which produces the general state of euphoria, a false sense of wellbeing, in which everybody seems to prosper. Those who without inflation would have made high profits make still higher ones. Those who would have made normal profits make unusually high ones. And not only businesses which were near failure but even some which ought to fail are kept above water by the unexpected boom. There is a general excess of demand over supply-all is saleable and everybody can continue what he had been doing. It is this seemingly blessed state in which there are more jobs than applicants which Lord Beveridge defined as the state of full employment-never understanding that the shrinking value of his pension of which he so bitterly complained in old age was the inevitable consequence of his own recommendations having been followed.

Conclusion

Going back to the equity markets, it is true that the above ASEAN bourses have been in the NEGATIVE zone as of Friday’s close, based on a year to date basis, following a downdraft that began in early November of 2010.

But when you input ALL of the aforementioned event risks, the comparative correlations reveal that the string of bearish news have been tenously linked to the activities of the region’s stock markets, and even possibly to the local property markets. Thus, it is likely that these negative events or what is perceived as exogenous event risks represents as more of noise than of meaningful signals that could impact the markets for long, unless these events turnout for the worse.

In other words, domestic factors such as the credit induced boom from an artificially suppressed interest rates seem to undergird the search for yield dynamics which is likely the key driver of the local financial financial markets (not limited to the equities) and perhaps of the ASEAN markets as well.

And the palpably auspicious local climate seems to be complimented by a still accommodative (policy divergent) global monetary environment as seen by the shifting nature of corporate activities worldwide—a boom in merger activities of emerging markets, primarily in the BRICs.

The Bloomberg reports[10],

The merger boom that started in 2010 isn’t looking like any of the past three. The takeover binge of the 1980s was fueled by Michael Milken’s junk bonds; the late- 1990s wave of Internet and telecom deals, by inflated stock prices; and the private-equity frenzy that produced a record year for deals in 2007, by leveraged loans.

The more recent surge comes from the expanding BRIC economies -- Brazil, Russia, India and China -- and beyond. Deals are rising among the companies that supply raw materials to these countries. Worldwide deals in energy, power and basic materials made up about a third of the merger and acquisition market in 2010, compared with about 20 percent in the previous decade, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Companies with headquarters in emerging markets played a role in more than a third of 2010 takeovers, about twice their historical share.

Bottom line: Markets hardly ever move in a straight line (unless during episodes of hyperinflation). For as long as the key conditions that drives the current market trends persist, volatility can be read or construed as natural countercyclical flows present in every functioning markets. Hence, loosely correlated external event risks likely signify as false signals which largely appeals to the brain’s emotion processing mechanism—the amgydala[11] than as critical analysis.

[1] Barley Richard, Europe's Ratings Rage Is Misdirected, Wall Street Journal, March 11, 2011

[2] See “I Told You So!” Moment: Being Right In Gold and Disproving False Causations March 6, 2011

[3] Abs-cbnnews.com January hot money inflow of $428-M lowest in 6 months, February 18, 2011

[4] IMF.org Philippines: 2010 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report; Staff Statement; Public Information Notice on the Executive Board Discussion; and Statement by the Executive Director for Philippines March 2011

[5] See The Upcoming Boom In The Philippine Property Sector, September 2010

[6] Abs-cbnnews.com January bank lending at 21-month high, March 11, 2011

[7] Manila Bulletin, Banks' lending grows double-digit in January 2011, March 11, 2011

[8] See The Code of Silence On Philippine Inflation, January 6, 2011

[9] Hayek, Friedrich August Can We Still Avoid Inflation? The Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle

[10] Bloomberg.com Goldman Heads M&A Rankings Spurred by Commodities Demand in BRIC Economies, March 7, 2011

[11] Wikipedia.org Amygdala. Shown in research to perform a primary role in the processing and memory of emotional reactions, the amygdalae are considered part of the limbic system

![clip_image001[4] clip_image001[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj6Uav3jWBO7HlfZ_H22FRNFunpaVChbg4gBvrRB8C59JlG92hopl7kgmMBPq1OOHM8BT9fs-EdukmGzHlaBOgQPN7EFF2TVXfUXXAmfkO_LNXPiTlj3vmWrvZctOVZbBBVt36J/?imgmax=800)