``Experience is a dear school, but fools learn in no other”-Benjamin Franklin

It is very interesting to observe how the volatility in the marketplace can intensively sway the emotions of participants. Apparently, this is the reflexivity theory—the feedback loop mechanism between prices and expectations—at work.

On the one hand, there are those whose crowd driven sanguine expectations seems to have been dramatically fazed by an abrupt alteration in the actions of market prices, where the intuitive reaction is to frantically grope for explanations whether valid or not.

Nonetheless such instinctive reactions are understandable because it signifies our brain’s defensive mechanisms as seen through its pattern seeking nature, a trait inherited from our hunter gatherer ancestors for survival purposes, mostly in the avoidance to become a meal for stalking predators in the wildlife.

For this camp, the newly instilled fear variable has been construed as the next major trend.

On the other hand, there are those whose longstanding desire for a dreary outcome. They cheerfully gloat over the recent actions that would seem to have their perspectives momentarily validated.

Permabears, whom have lamentably misread the entire run, sees one day or one week of action as some sort of vindication. This pathetic view can be read as the proverbial “broken clock is right twice a day”.

This camp claims that the recent paroxysms in the marketplace would signify as a major inflection point.

I’d say that both views are likely misguided.

The Market Is Simply Looking For A Reason To Correct

It’s not that I have been pounding on the table saying that the global markets, including the Philippine Phisix, have largely been overextended[1] and that profit-taking activities should be expected anytime.

Albeit, considering that the global financial market’s frenzied upside momentum, the unprecedented application of monetary policies and its probable effects on the marketplace, and where overextensions are common fares on major trends (bull or bear), crystal-balling short term trends can be fuzzy[2].

Besides it isn’t our role to tunnel in on the possible whereabouts of short term directions of the markets, a practise which I would call as financial astrology, to borrow Benoit Mandelbroit’s terminology.

Yet in vetting on the general conditions of the global marketplace in order to make our forecasts, we should look at the big picture.

Figure 1: Global Markets: Correction Not An Inflection Point

What is said as a ‘crowded trade’ is where the consensus has taken a position that leaves little room for expansion for the prevailing price trends. And in the paucity of further participation of ‘greater fools’, profit taking which starts as a trickle gradates into an avalanche, or the account of high volatility.

In looking at the charts of Gold (left upper window), the Dow Jones World Index (right upper window) and the Euro (left lower window) one would observe that the crowded trade phenomenon under current market conditions may have been in place since the run up began mainly from August.

I say ‘may’ because this will always be subjectively interpreted.

And for those who use the charts as guide, the intensifying degree of overextension have been evident from the departure or from the widening chasm of price actions from that of the moving averages, particularly the 50-day moving averages (blue lines).

Figure 2: Bloomberg: ASEAN Hotshots Likewise In A Corrective mode

Figure 2: Bloomberg: ASEAN Hotshots Likewise In A Corrective mode

And the same market motions seem to affect the ASEAN bourses, which of late has assumed the role as one of the world’s market leaders[3] or as one of the best performers. ASEAN benchmarks, last week, almost reacted synchronically with most emerging markets or with developed economy bourses. Decoupling, anyone?

The Philippines Phisix, which grabbed the top spot among ASEAN contemporaries, fell the most (6.26%) this week among all Asian bourses.

The last time the Phisix had a major one week slump at a near similar (but worst) degree was in the week that ended June 19, 2009. Like today, in tandem with our neighbours and global activities, the Phisix then lost 7.7% (see figure 2 blue ellipse: Thailand SET-red, Indonesia’s JKSE-yellow, Malaysia’s KLSE-green, Phisix-orange). Of course what followed was not a collapse but a febrile upside spiral from where the Phisix has not looked back.

So from the hindsight view, everything seems perfectly clear, the overheating or the overextensions, applied in current terms, may have peaked and thus has prompted for the market’s current ‘reversion to the mean’. Yet such regression should not imply a major trend reversal as it is likely to be a short term process.

And thus the current spasms seen in the marketplace is likely to account for mostly a normative profit-taking dynamic than from either a fear based regression or as a major inflection point.

I would thus carryover on my earlier advice[4],

I am not a seer who can give you the exactitudes of the potential retrenchment. Anyone who claims to do so would be a pretender. But anywhere from 5-15% from the recent highs should be reckoned as normal.

Yet, one cannot discount the potentials of a swift recovery following the corrective process. This is why trying to “market timing”, in this “growing conviction” phase of the bullmarket, could be a costly mistake.

Reflexivity and The Available Bias

The reflexive price-expectation-real events theory simply states that price actions may influence expectations which eventually reflect on real events. Consequently, developments in real events may also tend to reinforce such expectations through the pricing channel, hence the feedback loop.

Since this theory operates on a long term dimension, it plays out to account for as the shifting psychological or mental stages of a typical bubble cycle.

In other words, it would take sustained intensive price actions or major trends to trigger major psychological motions that eventually pan out as real events.

A simple illustration is that if the current market downside drift would be sustained, then the public may interpret the formative trend as an adverse development in the real world. Subsequently, people’s actions will be reflected on the economic sphere via a recession or another crisis. Hence, the price actions emanating from evolving negative events get to be reinforced in the stock markets-via a reversion to a bear market.

Unfortunately, there appears to be a problem in applying this theory in today setting; the reason is that the opinions from the marketplace seem to be tentative over what constitutes as the real cause and effect.

In short, the public’s pattern seeking character refuses to accept the profit taking countercyclical actions of the markets, and instead, looks for current events from which to pin the blame on or associate the causality nexus.

Again we understand this as the available bias.

Available Bias: China’s Battle With Inflation

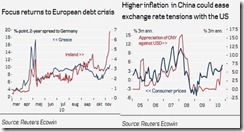

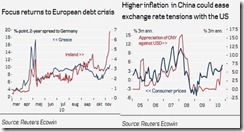

There have been two dominant factors from which the mainstream has latched the recent stress in the global markets on (see figure 3): one is China’s war with inflation and the other is the political tumult over Ireland.

Figure 3: Available Bias: Ireland Debt Crisis and China’s Tightening (charts from Danske Bank[5])

Friday’s 5.2% dive in China’s Shanghai Composite Index has been ascribed to the unexpected surge in inflation data[6] that has prompted Chinese authorities to reportedly raise bank requirements[7] to stanch credit flows coupled with rumors over more interest rate increases.

The selloff percolated to the commodity markets and rippled through emerging markets which laid ground to the rationalization of the supposed contagion effects from a potential curtailment of global economic growth on a tightening monetary environment in China.

It’s funny how the mainstream repeatedly argues over a myriad of fundamental issues supposedly affecting the markets when all it seems to take is the prospects of a credit squeeze to bring about a fit in the markets. This only proves our case that global stock markets have been mainly driven by inflationism (artificially suppressed rates and the printing of money).

China has been no stranger to such interventionism where the stock markets have been repeatedly buffeted by her government’s struggle, over the past year, to contain the so-called inner demons or a progressing bubble cycle (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Shanghai Composite: Another Government Instigated Drubbing (from stockcharts.com)

If I am not mistaken these interventions were interspersed from sometime mid 2009 until the 1st quarter of 2010. The net result over the past year has been a consolidation phase in the Shanghai Composite Index (SSEC) albeit a negative 8.9% return on a year to date basis.

Nonetheless, China isn’t likely to resort only to monetary tools but also through the currency mechanism. China would likely allow her currency to appreciate as part of the mix in her ongoing battle against bubble cycles.

And on the consumption based model, the appreciating the yuan is likely to spur internal demand that would further increase demands for commodities and trade flows with emerging markets. But this would be too simplistic, if not myopic.

Yet even if this is partly valid, then this only shows that the sell-off had been exaggerated which will likely be self corrected over the coming sessions.

The currency factor will not, by itself, likely do the trick, for the simple reason that the manifold parts of any economy have different costs sensitivity and that the distribution of costs for corporations are likewise varied in terms of ownership (private or state owned or mixed), per industry or per geographic boundaries and many other factors.

While the currency factor will partly help in the adjustment towards the acquisition of higher value added industries, a transition towards more convertibility of the yuan would allow international trade to be facilitated by China, instead of relying solely on the US dollar. Of course this could also function as one possible solution to China’s concern over the US Federal Reserve’s QE 2.0[8].

Thus more liberal trade and investment policies must compliment in the prospective adjustments in the yuan in order to have more impact.

Fixating on the currency elixir on the premise of “ceteris paribus” constants is all being out of touch with reality, applying models notwithstanding.

Available Bias: Political Kerfuffle Over Ireland

The second factor in the latest market stress, as shown in figure 3, is being imputed to the re-emergence of credit quality concerns over the periphery nations in the Euro zone, particularly that of Ireland which seems to be spreading to the other crisis stricken PIIGs.

As part of the crisis resolution mechanism, reports say that Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel is requiring investors to take write-offs in sovereign rescues[9]. And on this account Germany has been pressing Ireland to seek aid from multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the EU commission in transition. A route so far downplayed by the government of Ireland.

And apparently the Merkel position has clashed with that of European Central Bank Jean Claude Trichet who said that having investors to suffer from losses under present conditions would ‘undermine confidence’.

To add, the ECB’s modest purchase of government bonds[10] have reportedly not helped in allaying concerns over such political impasse. Another way to see it is that the ECB could be using the markets as leverage to extract concessions in behalf of several interest groups.

This makes the debt problems over at the PIIGS a politically motivated one.

Of course in the understanding of the ethos of politicians, should the stalemate go out of hand, we should expect hardline positions to reach for a compromise or adapt a pacifist approach unless these politicians would be willing to put to risks the Euro’s survival.

So far what is being portrayed as an infectious credit crisis, similar to the Greek episode early this year, has been largely isolated as major credit market indicators appear to be unruffled yet by the political kerfuffle in the Eurozone (see figure 6).

Figure 6: Credit Markets Still Unaffected By The Ireland

There are hardly any signs of bedlam over at the credit markets if we measure the diversified corporate cash indices in the US (left window) and or the 3m LIBOR OIS spread (right window), both measured in the US (red line) and the Euro (blue line). The 3M LIBOR OIS spread is the interest rate at which banks borrow unsecured funds from other banks in the London wholesale money market for a period of 3 months[11] and is a widely watched barometer of distress in money markets.

In fact, these credit indicators have hardly manifested any signs of contagion, even if we are to take the Greece episode early this year as a yardstick.

Figure 6: PIGS Equities Not In Unison With Credit Markets (chart from Bloomberg)

In addition, considering the record spreads between the debts of Eurozone’s periphery with that of Germany, one should expect such strains to be vented hard on their respective equity markets.

Yet despite being significantly down on a year to date basis, equity markets appears to have been little affected, as shown by Ireland’s Irish Overall Index (green) Portugal’s PSI General Index (orange) Greece’s Athens Composite Share (yellow) and Spain’s MA Madrid Index (red), all of which seem to be in a consolidation phase.

One may observe that Spain and Portugal’s benchmark seem to be trending down of late, that’s because they have been moving higher from the 2nd quarter, this, in contrast, to Greece and Ireland whose equity markets seem to be base forming.

Thus in summing up all these, I conclude that a potential major inflection point on the global equity markets emanating from the so-called contagion risks from the aftershocks in the PIIGS credit markets as largely unfounded.

One can add signs of resurfacing of some of the debt woes of Dubai[12], yet evidence suggests that today’s market actions is no more than an exercise of profit taking finding excuse in current events.

As a final note, I’d like to further emphasize that the Fed’s QE 2.0 seems to be failing in its mission to lower interest rates as US treasury yields have turned higher in spite of the recent market pressures (go back to figure 1 bottom right window). Of course, another way to look at it is that they seem to be succeeding in firing up inflation.

Moreover, the rally in the US dollar, despite the so-called return of risk aversion, likewise seems tepid.

So there seem little signs of a repetition of 2008 as many permabears have envisioned.

Overall the current market turbulence signifies as plain vanilla profit taking unless prices would be powerful enough to alter expectations that eventually would be reflected on real events.

[1] See An Overextended Phisix, Keynesians On Retreat And Interest Rate Sensitive Bubbles, October 25, 2010

[2] See Should We Chart Read Market Actions From QE 2.0?, November 7, 2010

[3] See Global Equity Markets Update: Peripheral Markets On Fire, Philippines Grabs Lead In ASEAN, November 4, 2010

[4] See Political Spin On The Philippine Economy And An Overextended Phisix, October 10, 2010

[5] Danske Bank, Focus turns from QE to debt crisis, Weekly Focus, November 12, 2010 p.1

[6] New York Times, China’s Inflation Rose to 4.4% in October, November 10, 2010

[7] Wall Street Journal, PBOC To Raise Major Bank's Reserve Ratio By Extra 50 BPs – Sources, November 11, 2012

[8] Businessweek/Bloomberg China Says Fed Stimulus Risks Hurting Global Recovery, November 5, 2010

[9] Bloomberg.com Germany Said to Press Ireland to Seek European Aid, November 14, 2010

[10] Danske Bank loc cit p.4

[11] St. Louis Federal Reserve The LIBOR-OIS Spread as a Summary Indicator, 2008

[12] Businessweek/Bloomberg Dubai ruler's firm talks with banks over debt load, November 11, 2010