Philippine bonds ended the year with a rally that partly offset some last week’s selloffs.

Also since no trend goes in a straight line and given the sharp moves of the past weeks, a rally should be expected.

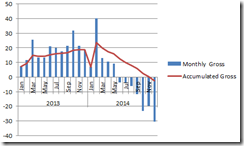

Today’s yearend rally has normalized the 4 and 5 year inversion from last week.

However, today’s rally hasn’t changed the dramatic flattening of the domestic yield curve seen over the past month.

Let me deal with an objection that I have recently received.

Obviously annoyed by my post, an internet troll recently wrote: “Yields spiked simply because of the long holiday. A lot of traders wanted to sell, and few wanted to buy, because of fears that something might happen between Dec 3 and Jan 5 (many of them would probably take Dec 29 off). Basic supply and demand. If/When nothing happens, expect rates to fall back in the new year.”

The troll ended with snide ad hominems.

The above suggests that the current spikes in the yield curve have been about the “long holiday”.

In celebration of Christmas, there are at least 5 public holidays in the last two weeks of December. I say “at least” because the government tends to declare unilaterally some in-between working days as holidays. This means long holidays has been a tradition in the Philippines. So fundamentally, to imply of ‘seasonality’ from long holidays means that turmoil in Philippine treasuries should consistently occur as an annual event!

A glimpse at the chart of yields of various Philippine treasury maturities will expose of the general invalidity of this claim (as shown below).

Paradoxically, the current turbulence in Philippine bond markets has been attributed to “fear” out of the long holidays.

What has not been specified has been the motivation of the “fear” which produced such actions, except to declare in conclusion that this should signify an anomaly. Why “fear” the long holidays if everything has been hunky dory? Because traders woke up with a hangover from their holiday bacchanalia and decided to become fearful to go into a selling spree???

So in the absence of the identification of cause/s, yet a generalization was made: Yields must go down because the claimant says so! See the wonderful self-proclaimed economic logic?!

Bluntly stated, nothing can ever go wrong with this boom! Warts, wrinkles and all blemishes have to be passionately denied out of existence!

Normally I would ignore such trolls, but the comment showcases what's wrong with the current conditions. They represent rabid denials which has part of the bubble psychology as indicated the anatomy of the bubble cycle above.

As a side note, in mainstream media, there seems to be a code of silence in recent developments at the domestic bond markets.

For instance this Bloomberg December 12 article reports on the big bond market gains in response to Moody’s upgrade: “The yield on peso bonds due November 2024 fell 16 basis points this week, the most since the five-day period ended Oct. 25 last year, to 4.17 percent in Manila, according to noon fixing prices from Philippine Dealing & Exchange Corp. The yield dropped 18 basis points, or 0.18 percentage point, today. That move was also the biggest since October 2013"

The following day, the “biggest” move “since October 2013” had been more than completely obliterated, yet media’s deafening silence on the event.

Good news reported, bad news censored? Why? Have bad developments not been real?

Going back to the objection, Dictionary.com defines “fear” as a distressing emotion aroused by impending danger, evil, pain, etc., whether the threat is real or imagined; the feeling or condition of being afraid.

In short, fear arises from a sense of heightened risk and or uncertainty. So how the heck can seasonality, which implies regularity, routine and predictability, generate “fear”?

If people are driven by incentives from subjective values, preferences and expectations, then the predictable end-of-the-year increased demand for liquidity should make financial institutions prepare for mundane events. Financial institutions may avail of interbank borrowing or BSP facilities (e.g. repos/ rediscounting) among the many modern tools in the financial toolkit. There won’t be need for abrupt liquidations of bonds.

And if bond markets have been reckoned as an option, the actions would be limited to some maturities, which has been the case for some yearend episodes. It is for this reason that Philippine bond markets have hardly demonstrated annualized turbulence as today.

In a nutshell, to rationalize current mayhem in the Philippine bond markets via proof of assertion, post hoc and begging the question— a bundle of flagrant logical fallacies—represents a rickety and inferior, if not a ridiculous way, to explain current events.

And because such comments have been predicated on faulty assumptions and premises they account for as blind faith to the perils of “This time is different” mentality which fits to a tee on the psychological aspect of what Harvard’s Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart observed as common denominator of every financial crises from 1800-2010 which they documented in their book

The essence of the this-time-is-different syndrome is simple. It is rooted in the firmly held belief that financial crisis is something that happens to other people in other countries at other times; crises do not happen here and now to us. We are doing things better, we are smarter, we have learned from past mistakes. The old rules of valuation no longer apply. The current boom, unlike the many previous booms that preceded catastrophic collapses (even in our country), is built on sound fundamentals, structural reforms, technological innovation, and good policy. Or so the story goes …

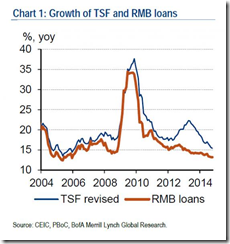

What has been the relationship among these key factors—exploding credit growth in both the banking system and the bond markets, declining statistical economic G-R-O-W-T-H, tumbling money supply growth rates and rising credit risks, as revealed by the resurgence in Philippine (and ASEAN) CDS spreads—to current bond market turbulence?

How about prospective US Federal Reserve policies? How will US interest rates impact domestic rates? Has all these been unrelated to the actions in Philippine bond markets? How about the soaring US dollar?

Again what incentives or expectations or events has triggered the “fear” via a scramble for liquidity in the bond markets?

We have also witnessed an inversion of 4 and 5 year yields last week, when was the last time the Philippine bond markets experienced this?

Does the following yield spreads from 2011 to 2014 (based on December monthly close from Investing.com) indicate that the Philippine bond markets have been about “long holidays”?

Except for the 10 year minus 2 year, even if we exclude this year’s actions, the short term-long term spread has exhibited a general flattening dynamic from 2011-2013.

This year's actions seems to only amplify an ongoing trend.

Yet the periodical December flattening dynamic resonates with the current activities over the past month.

Instead of an anomaly, the flattening of the yield curve is an indication of the business cycle in progress.

It has been a sign of monetary produced imbalances that has prompted credit markets to arbitrage on the asset liability mismatches via the spread differentials—whose windows have now been closing. It has been a sign of how credit expansion has engendered massive pricing distortions in the economy that has been demonstrated by inflationary pressures* which have now been reflected on the bond markets. And it has also been a sign that such credit expansion fueled boom has been backed by a lack of savings.

*As for relative inflation pressures, retail beer prices has risen 8%, my favorite fish ball vendor has not only had a decrease in size of the product, (value deflation or shrinkflation) recently the price has gone by 33%! (Previously Php 2 for every 4 pieces or 50 cents each now Php 2 for every 3 pieces or 66 cents each)

As Austrian economists Philip Bagus and David Howden explained: (bold mine)

Lacking adequate savings for the terms of the projects, these malinvestments must be liquidated. But when exactly will the recession set in? Two cases may be distinguished. In the first, the disturbance directly affects productive ventures. In the second case, financial intermediates first enter distress and only later affect productive enterprises.

In the first case, companies finance additional long-term investments with short-term loans. This is the case of Crusoe getting a short-term loan from Friday. Once savers fail to roll over the short-term loans and commence consuming, the company is illiquid (assuming other savers also curtail their lending activities). It cannot continue its operations to complete the project. More projects were undertaken than could be completed with the finally available savings. Projects are liquidated and the term structure of investments readapts itself to the term structure of savings.

In the second case, companies finance their long-term projects with long-term loans via a financial intermediary. This financial intermediary borrows short and grants long-term loans. The upper-turning point of the cycle comes as a credit crunch when it is revealed that the amount of savings at that point in time is insufficient to cover all of the in-progress investments. There will be no immediate financial problems for the production companies when the rollover stops, as they are financed by long-term loans. The financial intermediaries will absorb the brunt of the pain as they will no longer be able to repay their short-term debts, as their savings are locked-up in long-term loans. The bust in this case will reverberate backward from the financial sector to the productive sector. As financial intermediaries go bankrupt, interest rates will increase, especially at the long end of the yield curve, lacking the previous high-degree of maturity mismatching driving them lower. Short-term rates will also increase due to a scramble for funds by entrepreneurs who try to complete their projects. This will place a strain on those production companies that did not secure longer-term funding, or rule out new investment projects that were previously viable under the lower interest rates. Committed investments will not be renewed at the higher rates

Current developments in the Philippine bond markets suggest that yields have been rising across the curve but the pressure of increases has been in the short (bills) maturities than the longer bonds…thus the flattening. The flattening of the yield curve thereby signals the ongoing tightening of monetary conditions. Rising short term yields are symptoms of emergent strains in the Philippine financial system.

Let me further add that if the current ruckus in the bond markets will be sustained, the BSP will be forced to intervene. They may inject funds into pressured financial institutions, they may cut interest rates (contra mainstream expectations of higher rates), or at worst, if the problem spirals out of control, they may resort to bailouts.

The BSP will likely impose the same policies as her international peers: I recognize the problem of addiction but a withdrawal syndrome would even be more cataclysmic.

Yet interventions from the BSP won’t bring back “normality”, rather they’d be pushing the progressing credit problems down the road. So BSP actions may prompt for the current stress in Philippine bonds to temporarily backoff, but the deepening addiction and dependence by credit hooked institutions would mean more accumulation of systemic debt based problems overtime.

Via the law of scarcity, this means that eventually the developing entropy in the domestic credit markets, presently being ventilated in the bond markets, will reach a point to expose on the Potemkin Village pillared on a credit bubble; an inflection point from which the BSP won’t be able to control.

The great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises warned:

All governments, however, are firmly resolved not to relinquish inflation and credit expansion. They have all sold their souls to the devil of easy money. It is a great comfort to every administration to be able to make its citizens happy by spending. For public opinion will then attribute the resulting boom to its current rulers. The inevitable slump will occur later and burden their successors. It is the typical policy of après nous le déluge. Lord Keynes, the champion of this policy, says: "In the long run we are all dead." But unfortunately nearly all of us outlive the short run. We are destined to spend decades paying for the easy money orgy of a few years.

This blog has not been intended to join the selling of “their souls to the devil of easy money” by the consensus. Instead, in spite of social signaling costs, this blog has been intended to warn of its perils

With or without me, the Aldous Huxley rule will apply “facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored”.

History, economics and finance tell us that the obverse side of every credit fueled mania is a crash.

In spite of the above, have a wonderful new year!

.bmp)