All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.- Arthur Schopenhauer, German philosopher

So the much needed breather has finally arrived.

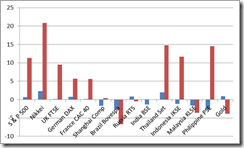

The Phisix fell by a hefty 2.62% this week accounting for the second weekly loss for the year and a year to date return of 14.48%.

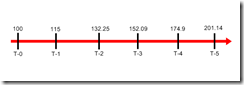

This week’s pause means Phisix 10,000 on August 2013 will be postponed but nevertheless remains a target for this year or 2014.

Again Phisix 10,000 will depend on the rate of progress of the manic phase, which I earlier described as

characterized by the acceleration of the yield chasing phenomenon, which have been rationalized by vogue themes or by popular but flawed perception of reality, enabled and facilitated by credit expansion.

Also the weekly loss has allowed Thailand’s SET (14.81% y-t-d, nominal currency returns) to overtake on the Phisix.

Nonetheless, equities of developed economies continue to sizzle. The Dow Jones Industrials are at fresh record highs (12.18% y-t-d), the US S&P 500 (11.29% y-t-d) also at the level of the previously established record highs in 2007 with the imminence of a breakout, while the Japan’s Nikkei continues to skyrocket from promises of more “liquor” from the Bank of Japan. Major European bellwethers have also been marginally up this week, UK’s FTSE 100 (9.52%), the German DAX (5.65%) and the French CAC (5.57%).

Yet signs are that the Phisix correction will likely be short-lived.

The media narrative of this week’s correction has been one of “valuations”.

A foreign analyst rationalizes this by saying[1] “While the story is a good one, there’s a limit to how much you can pay. It’s about the most expensive in the world.”

Mainstream media and the experts they cite, hardly reckon or explain on how and why valuations became the “most expensive in the world”. Most just seems satisfied with oversimplified interpretation that links “effects” as “causes”.

Philippine equities have reportedly been valued at 19.7 times projected 12 month earnings compared to her emerging market peers, where the MSCI Emerging market index supposedly trades at 10.9 times.

Yet a local buy side analyst from the same article claims that such profit taking phase represents an opportunity “to re-enter the market” supposedly because of “bullish” outlook of fundamentals.

So if 18-19 times earnings have been considered as a “buy”, then what indeed is “the limit to how much one can pay” for local stocks?

Bubble Mentality: This Time is Different

Such mentality reflects on the refusal for the market to retrench, a conviction that we have attained a “brave new world” or of the “denigration of history”—where people have come to believe that bad things will never happen to them

And as perilous as it is, as the mania develops, the sweeping rationalizations and justifications from mainstream experts, such as “the Philippines is resilient to external forces”, “is not crisis prone”, “has low debt levels”, among the many others, has reinforced the view that the boom is a one way street.

Such an outlook is shared not by mainstream “experts” but has been the evangelistic message preached by political authorities.

In a March 12th speech at the Euromoney Philippine Investment Forum, Philippine central bank Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) governor Amando M Tetangco, Jr admits that[3] “Domestic credit to-GDP ratio at 50.4 percent (Q4 2012) still ranks one of the lowest in the region”.

The red line from the chart above indicates of this adjusted official position[4].

Mr. Tetangco downplays the growing credit menace by using logical substitution, particularly comparing apples-to-oranges or by referencing credit conditions of other nations with that of the country.

I have previously pointed out of the irrelevance of such premise stating that “each nation have their own unique characteristics or idiosyncrasies”, such that “it is not helpful to make comparisons with other nations or region. Moreover, while many crises may seem similar, each has their individual distinctions” Importantly, “there has been no definitive line in the sand for credit events”[5]

Current domestic credit to-GDP conditions (50.4%) have almost reached the 1982 peak levels of 51.59%, when the Philippine economy then succumbed to a recession.

Since 2011, the ratio has grown at an average of 9.31% a year. At this rate, we will surpass the 1995 levels of 54.85% in 2013, and will almost reach the 1997 high of 62.2% in 2014 and far exceed the 1997 levels thereafter.

Yet there is nothing constant in social events for us to rely on numerical averages.

There are two ways were the ratio could explode higher that risks amplifying systemic fragility:

One, even if domestic credit growth remains static, the denominator [GDP] slows meaningfully, and

Second, domestic credit growth accelerates far more rapidly than the rate of GDP growth. The latter is the more likely the scenario, given today’s progressing manic phase.

In other words, given the current rate of debt buildup, we will reach or even surpass the pre-Asian Crisis high anytime soon, regardless of the assurances of the BSP.

Harvard’s professors Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, whose book “This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly” covers the historical account of various financial crisis over eight centuries throughout the world, aptly notes of people’s tendency to ignore the lessons of history.

In their preface they write[6], (bold mine)

If there is one common theme to the vast range of crises…it is that excessive debt accumulation, whether it be by the government, banks, corporations, or consumers, often poses greater systemic risks than it seems during a boom. Infusions of cash can make a government look like it is providing greater growth to its economy than it really is. Private sector borrowing binges can inflate housing and stock prices far beyond their long-run sustainable levels, and make banks seem more stable and profitable than they really are. Such large scale debt buildups pose risks because they make an economy vulnerable to crises of confidence, particularly when debt is short term and needs to be constantly refinanced. Debt fuelled booms all too often provide false affirmation of a government’s policies, a financial institution’s ability to make outsized profits, or a country’s standard of living. Most of these booms end badly.

I would say that all credit bubbles end badly.

In short, debt fuelled booms camouflages on the financial and economic imbalances that progresses unnoticed by the public. This eventually leads to a bust.

And “false affirmation” of current events reveals of how the public have been deluded or misled by false perceptions of reality only to be exposed as being left holding the proverbial empty bag.

“This Time is Different” as admonished[7] by Professor’s Reinhart and Rogoff

Throughout history, rich and poor countries alike have been lending, borrowing, crashing -- and recovering -- their way through an extraordinary range of financial crises. Each time, the experts have chimed, 'this time is different', claiming that the old rules of valuation no longer apply and that the new situation bears little similarity to past disasters."

Well “this time is different” or “old rules no longer apply” can be seen even in policymaking.

In recognition of the risks of “bubbly behavior” of “interest-rate sensitive” equity and property markets, the good governor Tetangco in the same speech remarked, (bold emphasis mine)

The recent global financial crisis showed that sole focus on price stability is not sufficient to attain macroeconomic stability. Policymakers need to deliver more than stable prices if they are to achieve sustained and stable growth. Price stability does not guarantee financial stability. The BSP, therefore, is attentive to pressure points that could impact on both price stability and financial stability.

To ensure financial stability we have utilized prudential measures to manage capital inflows and moderate, if not prevent, the build-up of excesses in specific sectors and in the banking system. Prudential policies are the instrument of choice and employed as the first line of defense against financial stability risks.

Wow. Not content with targeting “price stability”, the BSP governor deems that expansionary powers is necessary to deal with “surges” in foreign capital whom they associate as the primary cause of imbalances.

Every problem appears as a problem of exogenous origin with hardly any of their policies having to contribute to them.

The BSP also believes that they have the right mix of policy tools to attain their vision of “financial stability” utopia.

SDA Rate Cuts will Fuel Asset Bubbles and Price Inflation

However, in disparity with the confidence exuded by the BSP governor, the BSP seems to be in a big quandary.

Last week, they lowered interest on Special Deposit Accounts (SDA)[8]. SDAs are fixed-term deposits by banks and trust entities of BSP-supervised financial institutions with the BSP[9]. The BSP have used SDAs as a policy tool to “mop up” or sterilize liquidity in the system.

The lowering of SDA rates has been implemented allegedly to discourage the inflow of foreign portfolio investments that will likewise “temper” the appreciation of the local currency the peso. Moreover, lowering SDA rates has been supposedly meant to encourage “banks to withdraw some of their funds parked in the BSP, thereby increasing money circulating in the economy”. BSP’s Tetangco further dismissed the threat of inflation risks from such actions[10].

So by redefining inflation as hardly a consequence from additional supply of money, the BSP thinks that they can wish away inflation through mere edict.

Yet if “inflation is always and everywhere”, according to the illustrious Nobel laureate Milton Friedman[11], “a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output”, then the BSP’s policies will backfire pretty much soon.

Unleashing or emancipating part of the record holdings of 1.86 trillion pesos (as of mid February) of SDAs will intensify the inflation of the domestic credit bubble, fuel and exacerbate the manic phase of “bubbly behavior” of property and equity markets and subsequently prompt for a possible spillover to price inflation.

Thus political efforts to attain “financial stability” will lead to the opposite outcome: price instability and the risks of greater financial volatility. Such policies, in essence, underwrite bubble cycles and stagflation.

And because inflation has relative effects on society the likely ramification is that of social upheaval.

As the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises wrote[12] (bold mine)

Inflation does not affect the prices of the various commodities and services at the same time and to the same extent. Some prices rise sooner, some lag behind. While inflation takes its course and has not yet exhausted all its price-affecting potentialities, there are in the nation winners and losers. Winners—popularly called profiteers if they are entrepreneurs—are people who are in the fortunate position of selling commodities and services the prices of which are already adjusted to the changed relation of the supply of and the demand for money while the prices of commodities and services they are buying still correspond to a previous state of this relation. Losers are those who are forced to pay the new higher prices for the things they buy while the things they are selling have not yet risen at all or not sufficiently. The serious social conflicts which inflation kindles, all the grievances of consumers, wage earners, and salaried people it originates, are caused by the fact that its effects appear neither synchronously nor to the same extent. If an increase in the quantity of money in circulation were to produce at one blow proportionally the same rise in the prices of every kind of commodities and services, changes in the monetary unit's purchasing power would, apart from affecting deferred payments, be of no social consequence; they would neither benefit nor hurt anybody and would not arouse political unrest. But such an evenness in the effects of inflation—or, for that matter, of deflation—can never happen.

In short, BSP actions on SDAs can be analogized as playing with fire, and those who get burned will be the public.

And today’s correction phase in the PSE will likely be ephemeral.

And the potential shift from SDAs to the market will serve as another enormous force that will underpin the coming rally in the Phisix that would lead to the 10,000 levels.

But there seems to be another story behind the lowering of SDA rates.

Reports say that the BSP has nearly exhausted on the available stock of government bonds on their balance sheet to sell to the public[13]. Domestic sovereign bonds have been used as instrument to intervene in the currency markets by the BSP.

Unlike central bank of other countries as South Korea and India, the BSP is said to be legally constrained to issue their own bonds. The BSP is only allowed to issue “certificates of indebtedness” only “in cases of extraordinary movement in price levels” according to Section 92 Article 5 of the New Central Bank Act (Republic Act 7653).[14] So the BSP has been negotiating with the national government to authorise issuance of BSP bonds.

SDAs have been reported to be the “biggest drain on the BSP finances” resulting to the reduction of the BSP’s “net worth” from a surplus of 115 billion pesos in January 2012 to only 37.9 billion pesos in November of the same year. Earnings from US dollar and euro assets have failed to compensate for SDA operations.

In short, sterilization via the SDAs may have been an obstacle to the BSP’s operations and financial conditions. And this has prompted the BSP to relax on SDAs from where all sorts of rationalizations have been used to justify on such actions. Such may also represent politicking between political agencies.

Yet the financial world speculates that the prospects of reduced interventions from the BSP via limited access to national sovereign bonds may lead to a stronger peso. This could be a possibility, but I doubt that this would be the dominant factor.

Instead I am inclined to think that given the politics of the peso (appeal to the voters of OFW families and exporters) and of the dominant politics of social democracy, this provides the opportunity and justification for the national government to go on a spending splurge, through the issuance of more debt instruments that will be intermediated through the domestic banking system with the BSP. They will be labeled as spending meant for infrastructure and other social services, when such will be used mainly to “manage the peso”.

Yet increases in government debt will compound on the accelerating systemic debt levels.

The other option is for the national government, via the congress, is to allow the BSP to issue their own bonds which empowers the BSP to parlay on the politics of the peso.

Having both options may not be far-fetched scenario.

Capital Flows: Myth and Reality

I would further add that international capital flows, the du jour bogeyman of central banks, are really not the culprit of financial instability or price inflation as these latter two variables belongs to the realm of domestic monetary policies.

As Wall Street financial analyst Kel Kelly explains[15], (bold mine)

The notion of capital flows and money crossing borders is misunderstood by most people. Except for physical paper bills belonging to tourists, to drug dealers, or to foreign workers sending cash earnings home to relatives, money does not cross borders. Money generally remains in the country to which it belongs — and merely changes ownership. As this section will show, "speculative" money "flowing across borders" really consists only of the domestic central bank trying to keep its currency artificially priced.

So called "capital" or "hot money" does not "flow" from one country of origin into another country. However, money created in one country can be — and is, to a limited degree — used to buy the currency of another country and direct it into the purchase of asset prices in that country (bidding asset prices higher in the process). If a disproportionate amount of local currency is channeled into asset prices in a country, less currency is being spent on goods and services in the economy, causing consumer prices to fall.

But in reality, consumer prices in countries with booming asset markets do not usually fall while asset prices rise; both usually rise in tandem. This is because the local money supply is increasing, and pushing up both classes of prices (i.e., financial assets and consumer prices), even though one is rising faster than the other. It is therefore local money, not foreign money, inflating assets.

In short, spiralling prices is a function of yield chasing mentality powered by domestic credit and money expansion. Entry of foreign funds only changes the composition of the ownership of asset prices and does not necessarily constitute or equate to rising of asset prices.

And there is no money flows in the asset markets.

As I previously wrote[16],

Simply said, the presence foreign buyers don’t necessarily extrapolate to higher prices. This would depend on the valuation of every participant, whether the foreigner acts for himself or in behalf of a fiduciary fund from which his/her valuations and preferences would translate into action.

If the foreigner is aggressive then he/she may bid up prices. But again since people’s valuations differ, the scale of establishing parameters for each action varies individually.

A foreign participant can also be conservative, who may rather patiently accumulate, than bid up prices.

And speaking of foreign portfolio investments, the BSP reported that for February, registered foreign investments totalled $2.1 billion[17]. This has been 24.6% lower than from $2.8 billion last January. Most of these or 76.4% were directed at the PSE listed companies, particularly holding firms (US$474 million), banks (US$332 million), property companies (US$211 million), telecommunication firms (US$151 million), and utility companies (US$123 million).

One would note that the ranking of foreign buying essentially reflects on the returns of the PSE sectors which has been led by Property-holding-financial industries of which have been the primary objects of today’s credit bubble

Paul Volcker: Central banking “Hubris”

And going back to central bank policies, like Bank of Thailand’s deputy governor Mr Pongpen Ruengvirayudh, the BSP honcho Mr. Tetangco acknowledges of the dynamics of a bubble, and of the growing rate of domestic credit. But both categorically denies of the risks of respective domestic bubbles. That’s because they believe that “old rules of valuation no longer apply” and that they think that they possess divine omniscience or a magic wand that will successfully control or manage markets and the laws of economics in line with their visions.

In stark contrast to such chimerical outlook, in a March 13 2013 speech, former US Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker, a retired colleague of theirs, takes to task conventional central bankers at an economic conference sponsored by the Atlantic magazine.

Mr. Volcker holds them as unaccountable and as inept for the heavy cost paid from the “failure to recognize the implications of behavior patterns and speculative excesses in the financial markets that culminated in the crisis”[18]

Mr. Volcker has even more strident words on what he sees as “hubris” from contemporary central banking peers: (bold mine)

I do see a risk of what I consider a strange theory that these all-powerful central banks can play a little game. And when you want to expand – let’s have a little inflation that peps it up. But, of course, as soon as it gets a little big we’ll shut it off and then we’ll bring it down again. There is no central bank that I know of that has ever exhibited the capacity for that kind of fine-tuning. And if they lose sight of the basic role of a central bank is to maintain price stability, stability generally – the game will sooner or later be lost. That doesn’t mean you’re going to off in the next few years on some great inflationary boom – an inflationary process. But this hubris that somehow we have the tools that can manage in a very defined way little increases or decreases in the inflation rate to manage the real economy is nonsense. Did I say that strongly enough?

Add to this, even more bizarre has been the concept where increases in asset prices have been seen or read by policymakers as signs of ‘stability’, whereas, decreasing asset prices have been viewed or interpreted as ‘instability’ which for them requires interventionist actions.

The fact of the matter is that these are symptoms of artificially inflated unsustainable booms that results to its natural corollary—asset deflation.

So when authorities talk about focusing on ‘financial stability’, this should serve as warning signals over the risks of a blossoming manic phase of a maturing bubble process in motion.

Bottom line: This week’s correction mode in the Phisix may possibly continue, perhaps headed towards a 5-10% level from the recent peak. However, such retrenchment phase is likely to be one of a short duration.

The sustained manic “This time is different” mentality both reflected on market participants as well as in political authorities expressed through policymaking as signified by this week’s cut in SDA rates by the BSP, will likely rekindle another bout of buying binge soon, unless external events may cause some disruption. The effects of taxing depositors to bailout Cyprus could signify as “one thing leads to another” via the growing risks of bank runs in the Eurozone[19].

And given the intense politicization of the marketplace, expect financial markets to remain highly volatile, as this will be marked by sharp advances and declines.

[9] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas: Monetary Policy - Glossary and Abbreviations Special Deposit Accounts – Fixed-term deposits by banks and trust entities of BSP-supervised financial institutions with the BSP. These deposits were introduced in November 1998 to expand the BSP's toolkit for liquidity management. In April 2007, the BSP expanded the access to the SDA facility to allow trust entities of financial institutions under BSP supervision to deposit in the facility.

[11] Milton Friedman The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory (1970) Wikiquote