Economic weakness of China and of high oil prices, which supposedly threatens global economic growth, has been attributed by media as the cause for this week’s anemic performance by global stock markets[1].

The Perils of Relying on Media’s Availability Heuristics

It’s has been the intuitive inclination of media to oversimplify the causation process in the narration of events. In reality, such oversimplification represents the available bias or availability heuristic—judgment based on what we can remember, rather than complete data[2] or the fallacy of attributing current events to most recent market actions—than about the real forces driving the market’s action.

And applying heuristics to market analysis can lead one astray, and thus, amplifies the odds of erroneous decision making. One of Warren Buffett’s most precious investment advice has been

Risk comes from not knowing what you're doing.

This applies to sloppy thinking based on heuristics.

Financial markets rarely moves in a straight line.

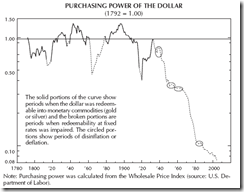

If they do, then markets must be experiencing an episode of extreme stress, symptomatic of the ventilation of acute systemic imbalances on the marketplace. They appear in the form of a blowoff phase (climax) of a bubble cycle or of hyperinflation in motion.

Yes, stock markets soar to the firmament during episodes of hyperinflation. Although whatever gains seen is largely illusory as the local currency, enduring hyperinflation, depreciates so much faster than the nominal price gains in stock market values.

Zimbabwe which suffered from hyperinflation just a few years back saw its stock markets zoom[3], so as with the German stock market[4] during the horrific days of the Weimar hyperinflation.

Here, the role of stock markets shifts from intermediaries of capital to a monetary lightning rod. Of course, this cannot be explained by the orthodoxy of earnings or corporate fundamentals, since the public’s flight to safety motives has been driven by the desire to protect one’s wealth through ownership of real assets.

As one would note, stock markets becomes the fiduciary alternative to money under such conditions.

Yet in a normal bullmarket (or boom phase of a credit driven bubble cycle), intermittent profit taking sessions should be expected. This is where profit taking sellers of financial securities overwhelm the buyers that result to countertrend price actions. Nevertheless, financial markets tend to move in a general direction (uptrend, consolidation or downtrend) for a given period of time, despite interim countercylical fluctuations.

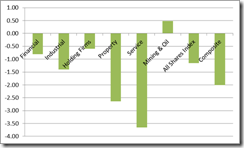

The pulsating surge of key global equity benchmarks suggests that this week’s retracement represents more of a profit taking process than signs of anxiety, where the losses (left window) have hardly dented on the enormous nominal local currency gains posted by the bellwethers of major economies since the start of the year (right window).

The US S&P 500 posted its second weekly loss in 12 weeks into 2012, while the Germany’s Dax, Japan’s Nikkei and the Philippine Phisix had 3 non-consecutive weekly losses. So far this translates to 1 week loss for every 3 weeks of gains for the latter 3 and 1 loss for every 5 weeks of gain for the S&P. Of course past performance is no guarantee for future outcomes.

In addition our ASEAN neighbors, Indonesia and Malaysia whom has largely missed the recent bullrun seems to defy last week’s profit taking mode. Instead they have posted modest gains, which in essence, incrementally closes on the gap between the region’s leaders the Philippines and Thailand and the laggards.

Moreover, Thailand has finally caught up with the Phisix.

So if we are seeing a rotational process among sectors and in the PSE and issues within specific sectors, then we seem to see the same process at work in global equity benchmarks.

The rotation in relative performances has been symptomatic of an inflationary boom.

As for media’s narrative, one week does not a trend make.

Huge Credit Easing Policies Means Profit Taking Will Be Short Term

If we examine the chart patterns of US equities, they seem to imply that this week’s profit taking mode might be extended.

And this could coincide with a breakdown of the ascending wedge pattern of the S&P 500 below.

Aside from the S&P, the Dow Jones Industrials and the Nasdaq chart patterns seem to tell the same tale.

What makes charts occasionally credible is that many believers can make such patterns a self-fulfilling process over the short run. And perhaps they can be augmented or complimented by trades based on algorithm or computer programs, which buy or sell triggers have been programmed to activate based on specific data points derived from chart patterns and or their corresponding indicators.

Yet any such breakdown could see some support at the 1,350 area. From Friday’s close, a downside move to this level will translate to about 3.3% retracement.

Yet chart patterns of the Philippine Phisix reveals of a subtle difference compared to the US benchmarks.

The Phisix seems to be partly in a symmetrical triangle—fundamentally this is a trend neutral pattern, which either signals continuity or a reversal[5]. Yet the recent double bottom pattern breakout also seems to suggest of a fresh upside trend at work. The implication is that any correction may be short term and shallow.

The Phisix and the S&P has had loose correlations from the last quarter of 2010 until late last year, where there had been numerous accounts of divergent actions between the two bourses. As a reminder, divergence does not represent decoupling.

Their correlations seemed to have tightened only from last October, where the combined actions of major central banks have forcibly led to major short coverings, as well as, yield chasing arbitrages that has painted an aura of ‘recovery’ as evidenced by resurgent global markets.

Another important reminder is that it is a misguided notion to assume that the current financial market developments have entirely been about ‘liquidity’.

Since 2008, political actions have included the widespread alteration of the rules of the game (such as changes in accounting rules[6], easing of collateral requirements[7], indiscriminate changes in the rights of private ownership to sovereign debt[8], arbitrary determination of credit event conditions for derivatives contracts[9]), direct and indirect bailouts, guaranteeing access to credit, implicit and explicit guarantees on assets, manipulation of the yield curve, interest rate payment on excess reserves, market making, buyer of last resort, lender of last resort, and etc..., has not only been about liquidity (liquefying of illiquid assets) but about arbitrary interventions in various forms and degree. In short, today’s financial markets have massively been in violation of various forms property rights of the private sector to the benefit of the banking system and the welfare state.

The mass politicization of the markets has been distorting price signals and has been misdirecting the allocation of resources. The piper in the fullness of time will be paid.

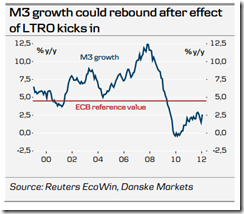

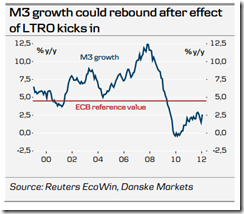

And given that the gist of the current tidal wave of major central asset purchasing programs have only been announced and put into action last month (such as ECB’s LRTO[10]), the effects of these massive cash infusions, compounded by the policy trends to adapt a negative rate regimes for many major emerging markets will likely put a floor on any recent corrections.

Thus it is unclear if the adverse signal emitted by these chart patterns, possibly signifying an extension of the corrective phase, will play out. And even if it does, any correction will likely be shallow.

Market Internals Reveal Profit Taking and Rotational Process

Yet market internals of the Phisix still exhibits some positive signs despite this week’s hefty correction.

True, decliners led advancers, but the spread between them has not deteriorated in a panic stricken scale as the previous sell-offs.

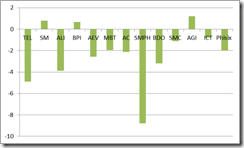

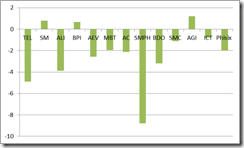

Moreover, of the 12 Phisix heavyweights representing 67% of the free float market cap last Friday, 3 posted gains and provided cushion to the index, specifically, Alliance Global [PSE:AGI], SM Investments [PSE: SM] and Bank of the Philippine Islands [PSE: BPI].

Meanwhile all the rest of the biggest caps posted losses led by SM Prime Holdings [PSE: SMPH], Philippine Long Distance Telephone [PSE:TEL], market leader Ayala Land [PSE:ALI] and Banco de Oro [PSE: BDO], all of which weighed on the index.

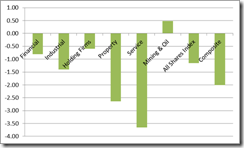

The decline as seen by the Phisix biggest market caps have equally been mirrored on the sectoral performance.

Again, we note that the mining index appears to have regained some appeal as many of the majors fell.

Finally foreign trades posted hefty net selling this week amidst a largely unchanged Peso.

But this came on the heels of the completion of the sale Alaska Milk Corporation[11] [PSE:AMC] from the seller, the Uytengsu family to the new owners the Dutch dairy giant Royal Friesland Campina for Php 12.86 billion.

My puzzle is that the buyer was a foreign group but the seller was a local group yet during the date of execution of the AMC trade, net foreign trade showed net selling almost to the tune of the AMC transaction.

Perhaps the foreign group incorporated a local company to execute the transaction, while the selling group, the Uytengsus’ equity ownership had been divested through a holding company incorporated abroad.

This could be another example of the inaccuracy of statistics which fails to capture the real developments behind each transaction.

The Political Imperative to Inflate the System

Bottom line: It is really very difficult to predict short term moves.

Nevertheless my basic premise still holds, the recent actions of major central banks combined with negative interest rate policy regime by the Philippine central bank, the BSP, as well as other emerging markets, will impact stock markets over the 3-6 months window as it has done before[12]. Most likely, we may see renewed selling pressures as these steroids come to a close.

Manipulating the financial markets including the stock markets has been part of the Bernanke’s doctrine[13] to save the banking system and indirectly to finance the welfare state. And the Bernanke creed seems to have been imbued as the de facto global policy handbook for central bankers.

And hawkish overtones[14] by some members of the US Federal Reserve or the ECB[15] may change as quickly, as so required by political exigency, especially when faced with the reemergence of selling pressures.

It would take a really big and nasty surprise and an equally static or passive or non response by central bankers to such event for the markets to feel pressure again.

And the only thing that may demobilize central bankers will be massive price inflation. As for politics, the arcane world of central banking has so far eluded the scrutiny of the benighted public.

[1] Businessweek.com Mounting global growth concerns push markets lower, March 23, 2012 Associated Press

[2] Changingminds.org Availability Heuristic

[3] Koning John Paul Zimbabwe: Best Performing Stock Market in 2007? April 10, 2007 Mises.org

[4] Nowandfutures.com Germany, during the Weimar Republic & the hyperinflation

[5] Incrediblecharts.com Triangles and Wedges

[6] Wikipedia.org Effect on subprime crisis and Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 Mark to Market Accounting

[7] The Euro Crisis Amidst the Cheer, Could the LTRO Be Storing Up Problems for Later?, February 29, 2012 Wall Street Journal Blog

[8] Kotok David R. Moral Hazard-CAC Cumber.com, February 23, 2012

[9] Reuters.com Deeper Greek losses 'unlikely' to trigger CDS -ISDA, October 27, 2011

[10] Weekly Focus, Concerns about fragile global recovery March 23, 2012 Danske Research

[11] Business.inquirer.net Uytengsus complete sale of Alaska Milk stake March 21, 2012

[12] Zero Hedge, Operation Twist Is Coming To An End: A Preview Of The Market Response March 19, 2012

[13] See US Stock Markets and Animal Spirits Targeted Policies, July 21, 2010

[14] Bloomberg.com Fed’s Bullard Sees Price Threat From G-7 Delaying Tighter Policy, March 23, 2012

[15] Bloomberg.com Asmussen Says ECB Must Start to Prepare Exit, Die Zeit Reports, March 21, 2012