Unfolding events in Cyprus may or may not be a factor for the Phisix or for the region over the coming days.

This will actually depend on how the bailout package will take shape, and importantly, if these will get accepted by the “troika” (IMF, EU and the ECB), whose initial bid to force upon a bank deposit tax indiscriminately on bank depositors had been aborted due to the widespread public opposition.

So far, the Cyprus parliament has reportedly voted on several key measures[1] as nationalization of pensions, capital controls, bad bank and good bank. Reports say that the Cyprus government has repackaged the bank deposit levy to cover accounts with over 100,000 euros with a one-time charge of 20%[2]!

The troika demands that the Cyprus government raise some € 5.8 billion to secure a € 10 billion or US $12.9 billion lifeline.

If there may be no deal reached by the deadline on Monday, then Cyprus may be forced out of the Eurozone. Then here we may see uncertainty unravel across the global financial markets as a Cyprus exit, which will likely be exacerbated by bank runs and or social turmoil, may ripple through the banking system of other nations.

However, if Cyprus gets to be rescued at the nick of time, then problems in the EU will be pushed for another day.

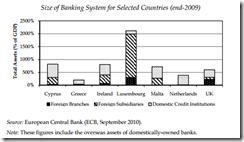

Nonetheless unfolding events in a 1 million populated Cyprus, but whose banking system has been eight times her economy[3] has so far had far reaching effects.

The Cyprus “bail in” has already ruffled geopolitical feathers.

Germans are said to been reluctant to provide backstop to Cyprus due to nation’s heavy exposure to the Russians, where the latter comprises about a third of deposits of the Cyprus banking system. Much of illegal money from Russia has allegedly sought safehaven in Cyprus.

The Cyprus-Russia link goes more than deposits. They are linked via cross-investments too.

Some say that the Germans had intended to “stick it to the Russians”[4].

On the other hand, Russians have felt provoked by what they perceive as discrimination.

Meanwhile events in Cyprus have also opened up fresh wounds between Greeks and the Turkish over territorial claims[5].

The other more important fresh development is of the bank deposit taxes.

Where a tax is defined[6] as “a fee levied by a government on income, a product or an activity”, deposit taxes are really not taxes, but confiscation.

Some argue that this should herald a positive development where private sector involvement takes over the taxpayers. Others say that filing for bankruptcy would also translate to the same loss of depositor’s money.

Confiscation is confiscation no matter how it is dressed. It is immoral. Private sector involvement is forced participation.

Bankruptcy proceedings will determine how losses will partitioned across secured and unsecured creditors and equity holders. Not all banks will need to undergo the same bankruptcy process. Yet confiscation will be applied unilaterally to all. For whose benefit? The banksters and the politicians.

And one reason bondholders have been eluded from such discussion has been because Cyprus banks have already been pledged them as collateral for target2 programs at the ECB[7].

The more important part is that events in Cyprus have essentially paved way for politicians of other nations, such as Spain and New Zealand[8], to consider or reckon deposits as optional funding sources for future bailouts.

With declining deposits in the Eurozone[9], the assault on savers and depositors can only exacerbate their financial conditions and incite systemic bankruns.

So confidence and security of keeping one’s money in the banking system will likely ebb once the Cyprus’ deposits grab policies will become a precedent.

This is why panic over bank deposits have led to resurgent interest on gold and strikingly even on the virtual currency the bitcoin[10]. The growing public interest in bitcoin comes despite the US treasury’s recently issued regulations in the name of money laundering[11].

Such confiscatory policies will also redefine or put to question the governments’ deposit insurance guarantees. Not that guarantees are dependable, they are not; as they tend increase the moral hazard in the banking system as even alleged by the IMF[12].

Deposit guarantees are merely symbolical, as they cannot guarantee all the depositors. Given the fractional reserve nature of the contemporary banking system, if the public awakens to simultaneously demand cash, there won’t be enough to handle them. And obliging them would mean hyperinflation. That’s the reason the dean of the Austrian economics, Murray Rothbard calls deposit insurance a “swindle”[13].

The banks would be instantly insolvent, since they could only muster 10 percent of the cash they owe their befuddled customers. Neither would the enormous tax increase needed to bail everyone out be at all palatable. No: the only thing the Fed could do — and this would be in their power — would be to print enough money to pay off all the bank depositors. Unfortunately, in the present state of the banking system, the result would be an immediate plunge into the horrors of hyperinflation.

So governments will not only resort to taxing people’s savings implicitly (by inflation), they seem now eager to consider a more direct route: confiscation of one’s savings or private property. Note there is a difference between the two: direct confiscation means outright loss. Inflation means you can buy less.

Finally, losses from deposit confiscation, and its sibling, capital controls will lead to deflation.

Confiscatory deflation, as defined by Austrian economist Joseph Salerno, is inflicted on the economy by the political authorities as a means of obstructing an ongoing bank credit deflation that threatens to liquidate an unsound financial system built on fractional reserve banking. Its essence is an abrogation of bank depositors' property titles to their cash stored in immediately redeemable checking and savings deposits[14].

The result should be a contraction of money supply and bank credit deflation and its subsequent symptoms. This will be vented on the markets if other bigger nations deploy the same policies as Cyprus.

That’s why events in Cyprus bear watching.

[1] See Cyprus President Warned Friends of Crisis March 23, 2013

[2] New York Times Cyprus Makes Plan to Seize Portion of High-Level Deposits, March 23, 2013

[3] Constantinos Stephanou The Banking System in Cyprus: Time to Rethink the Business Model? 2011 World Bank

[4] Investopedia.com The Cyprus Crisis 101 March 19, 2013

[5] See Will Events in Cyprus Trigger a War? March 22, 2013

[7] Mark J Grant Why Cyprus Matters (And The ECB Knows It) Zero Hedge March 23, 2013

[8] John Aziz Guest Post: Whose Insured Deposits Will Be Plundered Next? Zero Hedge March 21, 2013

[9] The Economist Infographics March 23, 2013

[10] See Bitcoins: Safehaven from Cyprus Debacle and Officially Recognized by the US Treasury March 21, 2013

[11] International Business Times, US Treasury Department: Virtual Currencies (Read: Bitcoins) Need Real Rules To Curb Money Laundering March 22, 2013

[12] Buttonwood What does a guarantee mean? The Economist March 19, 2013

[13] Murray N. Rothbard Taking Money Back January 14, 2008 Mises.org

[14] Joseph Salerno Confiscatory Deflation: The Case of Argentina, February 12, 2002 Mises.org

1 comment:

I just heard about this thanks for infornasinya

Post a Comment