Before joining the euro, the Central Bank of Cyprus only allowed banks to use up to 30 percent of their foreign deposits to support local lending, a measure designed to prevent sizeable deposits from Greeks and Russians fuelling a bubble.

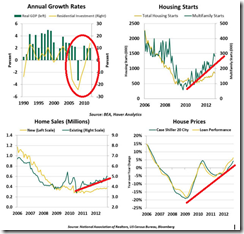

When Cyprus joined the single European currency, Greek and other euro area deposits were reclassified as domestic, leading to billions more local lending, Pambos Papageorgiou, a member of Cyprus's parliament and a former central bank board member said."In terms of regulation we were not prepared for such a credit bubble," he told Reuters.Banks' loan books expanded almost 32 percent in 2008 as its newly gained euro zone status made Cyprus a more attractive destination for banking and business generally, but Cypriot banks maintained the unusual position of funding almost all their lending from deposits.

"The banks were considered super conservative," said Alexander Apostolides an economic historian at Cyprus' European University, a private university on the outskirts of Nicosia.When Lehman Brothers collapsed in the summer of 2008, most of the world's banks suffered in the fallout, but not Cyprus's."Everyone here was sitting pretty," said Fiona Mullen, a Nicosia-based economist, reflecting on the fact Cypriot banks did not depend on capital markets for funding and did not invest in complex financial products that felled other institutions.

4. Overconfidence and Mania

Marios Mavrides, a finance lecturer and government politician, says his warnings about the detrimental impact on the economy of so much extra lending fell on deaf ears."I was talking about the (property) bubble but nobody wanted to listen, because everyone was making money," he said. (sounds strikingly familiar today—Prudent Investor)The fact that the main Cyprus property taxes are payable on sale made people hold onto property, further fuelling prices, Papageorgiou added…Michael Olympios, chairman of the Cyprus Investor Association that represents 27,000 individual stock market investors, said he too criticized the central bank for "lax" regulation that facilitated excessive risk taking.

A depositor would have earned 31,000 euros on a 100,000 euros deposit held for the last five year in Cyprus, compared to the 15,000 to 18,000 euros the same deposit would have made in Italy and Spain, and the 8,000 interest it would have earned in Germany, according to figures from UniCredit.Bulging deposit books not only fuelled lending expansion at home, it also drove Cypriot banks overseas. Greece, where many Cypriots claim heritage, was the destination of choice for the island's two biggest lenders, Cyprus Popular Bank -- formerly called Laiki -- and Bank of Cyprus.

The extent of this exposure was laid bare in the European Banking Authority's 2011 "stress tests", which were published that July, as the European Union and International Monetary Fund (IMF) were battling to come up with a fresh rescue deal to save Greece. (reveals how bank stress tests can’t be relied on—Prudent Investor)The EBA figures showed 30 percent (11 billion euros) of Bank of Cyprus' total loan book was wrapped up in Greece by December 2010, as was 43 percent (or 19 billion euros) of Laiki's, which was then known as Marfin Popular.More striking was the bank's exposure to Greek debt.At the time, Bank of Cyprus's 2.4 billion euros of Greek debt was enough to wipe out 75 percent of the bank's total capital, while Laiki's 3.4 billion euros exposure outstripped its 3.2 billion euros of total capital.The close ties between Greece and Cyprus meant the Cypriot banks did not listen to warnings about this exposure…

Whatever the motive, the Greek exposure defied country risk standards typically applied by central banks; a clause in Cyprus' EU/IMF December memorandum of understanding explicitly requires the banks to have more diversified portfolios of higher credit quality."That (the way the exposures were allowed to build) was a problem of supervision," said Papageorgiou, who was a member of the six-man board of directors of the central bank at the time.The board, which met less than once a month, never knew how much Greek debt the banks were holding, both Papageorgiou and another person with direct knowledge of the situation told Reuters.