Many are good at solving equations but not understanding them; others are good at understanding equations but not solving them ; a few are good at both understanding and solving equations; those left over who are neither good at solving equations nor understanding them, yet insist on doing mathematics, become economists. Nassim Nicolas Taleb

Swooning over to populist politics, Philippine media immediately acclaimed that the recent statistical 7.8% economic growth for the first quarter was “stunning”[1].

Behind the “Stunning” Economic Growth has been a “Shocking” Credit Boom

Let us take the “stunning” growth narrative from the Philippine government’s National Statistical Coordination Board[2]:

The robust growth was boosted by the strong performance of Manufacturing and Construction, backed up by Financial Intermediation and Trade.

On the demand side, increased consumer and government spending shored up by increased investments in Construction and Durable Equipment contributed to the highest quarterly GDP growth since the second quarter of 2010.

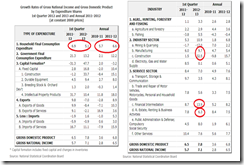

The following table[3] above from the NSCB highlights the areas which supposed delivered such “stunning” growth

One would note that the growth in the household final expenditure, which represents the “demand side” (red ellipses on left table), has been significantly below the booming supply side areas particularly construction, and financial intermediation (red ellipses on right table).

Curiously and ironically, the real estate segment of the economic growth data has risen almost at par with domestic demand even as the construction sector has taken a huge leap in contributing to such statistical growth.

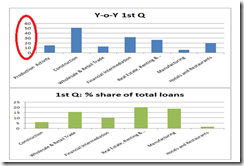

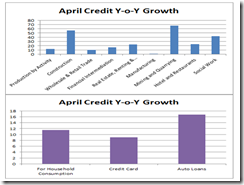

The table below exhibits the rate of growth of bank loans covering these sectors over the same period.

The BSP data reveals that bank credit growth for these sectors have been even more “shocking”.

While the banking system’s general loan growth has expanded by 15% in the first quarter year-on-year or more than double the rate of demand, construction and financial intermediation has zoomed by staggering 51.2% and 31.61% correspondingly!!!

Real estate Renting and Business Services, Hotel and Restaurants and Wholesale and Retail trade has likewise been in an astounding expansion mode. During the same period banking loans on these sectors grew by 26.24%, 12.49% and 19.19% respectively!

Earlier I said “ironic” because the 1st quarter statistical growth for the Real estate Renting and Business Services sectors grew by only 6.3% even as bank loans jumped by 26.24%. Where have borrowers from these sectors been channeling the loan proceeds?

Meanwhile the measly 5.9% credit growth in the manufacturing sector reflects on why this sector has not been a bubble.

Nonetheless the credit booming sectors now account for 53.25% of total banking loans.

Given the fantastic rate of credit growth, it would seem a puzzle why the Philippine economy grew by a miserly 7.8%.

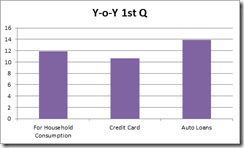

And it is important to realize that even as domestic demand, as measured by household consumption, expanded by 5.1%, such has “partly” been backed by credit growth. I say “partly” because only a scanty number of households have access to bank credit.

Bank loans to domestic households advanced by a “modest” 11.89% during the same period. This has been supported by the expanded use of credit cards 10.62% and a rise in auto loans 13.86%.

I say “modest” because even if household loans grew by more than double the rate household consumption, compared to the scale of bank credit growth in the supply side, the demand side credit surge looks like a cinch compared to the supply side.

Banking loans for April mostly resonates on the same 1st quarter trend but at a lesser pace of increases.

According to the latest BSP data[4], while general banking loans has moderately slowed, year-on-year credit to the construction sector remained resilient and swelled by 56.14%. The BSP’s press release again glosses over mentioning this data.

However credit figures seem to have eased for wholesale and retail trade 10.02, financial intermediation 15.89% and real estate related loans at 22.67%.

Meanwhile loans to the hotel and restaurant sector firmed at 23.67%. And bizarrely, the “politically incorrect” mining and quarrying sector posted a surprising 67.26% spike in loan growth.

On the demand side, household loans grew at again a “moderate” rate at 11.5%. This has been backed by “modest” expansions in credit cards (9.01%) and auto loans (16.69%).

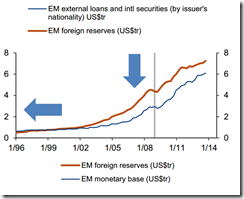

The easy money environment has also been evident in domestic money supply conditions.

Domestic liquidity (M3) increased by 13.2% on April (y-o-y) to reach Php 5.2 trillion. As the BSP notes[5],

The growth in money supply was driven largely by the sustained expansion in net domestic assets (NDA). NDA increased by 19.7 percent y-o-y in April from 25.3 percent (revised) in the previous month due largely to the continued increase in credits to the private sector of 14.3 percent, reflecting the robust lending activity of commercial banks. Similarly, claims on the public sector grew by 11.9 percent in April after rising by 15.0 percent (revised) in March, largely a result of the increase in credits to the National Government (NG).

The Philippine government has been actively tapping the credit markets for its expenditures as both revealed in the 1st quarter and in the April 2013 data.

Yet each peso the government spends is a peso not spent by the private sector. And every additional peso the government spends means higher taxes, bigger debt and or more inflation as time goes by.

All these imply that the foundations for such “stunning” statistical growth have principally been due to ballooning credit.

And according to Investopedia.com[6] credit means borrowed money “must be paid back to the lender at some point in the future.” In other words, such “stunning” pace of economic growth signifies a substantial frontloading of future growth to the present.

Worst, the current credit impelled growth dynamics extrapolates to a sustained massive buildup of imbalances particularly magnifying the risks of the tightly entwined or interdependent oversupply and overleverging.

Thus, take away the substance (credit), the form (statistical growth) will be exposed of its cosmetic unsustainable dynamic: Today’s manipulated boom will eventually metastasize into a bust.

Importantly behind the fanfare over such “stunning” statistical growth is the revelation of the dark side of the Philippine political economy.

Given that the fact that the large segment of the population remains unbanked or has little or no direct access to the banking sector, (the BSP estimates that only 21.5% of households have access to banks) and where 83% of the stock market cap have been held by a few families, such credit inspired asset (property-stock market) boom which has been reflected on statistical growth, embodies of a boom vastly tilted towards political and politically connected economic financial elites.

In short, current policies represent a transfer or a subsidy to these politically privileged classes at the expense of the average Pedro or Juan.

Sad to see how the public fall prey to such disinformation, which has been disguised as economics.

Yet what people cheer for today will redound to tears in the near future.

How Media Rationalizes the Phisix Selloff

The disclosure of the “stunning” economic growth came amidst a one day heavy sell-off in the Phisix.

It was “fascinating” to see a bewildered public agonizing over how such good news could be met by a fury of sellers. Many seemed lost, as seen by comments on different social media platforms.

Beguiled by the conventional wisdom that stock market performance reflects on the real state of the economy, I said “fascinating” because the marketplace has been conditioned to see that there is no way but up, up and away for the Philippine assets.

Last week may have brought back some reality to them

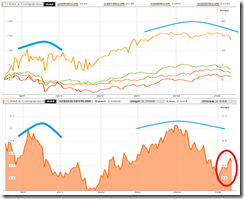

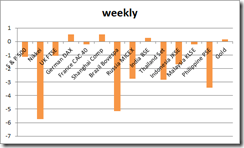

The Philippine Phisix slumped by 3.81% on Thursday May 30th partly in sympathy with Japan’s nose diving stock markets. Over the week, the Phisix lost 3.4%. Global markets have been mostly lower and such includes our ASEAN peers.

The Phisix meltdown had been rationalized by media as having been a regional phenomenon, from the prospective “tapering” of US Federal Reserve’s easing programs and from “expensive” valuations.

The above shows how current environment has turned from risk ON to risk OFF. Risk OFF extrapolates to a global, not just regional selling pressure.

And funny how the FED has repeatedly been talking about “exit” strategies from the start of the year[7], yet the supposed impact from FED communications would come only last week? Why?

In late April, chatters over “tapering” even changed to “extending bond buying”[8]. So the FED seems much in confusion as with the global markets deeply dependent on them.

The reason why tapering has been much in the news and justified as having influence to stock and bond markets have largely due to surging yields in US treasury paper claims and mortgage rates. US mortgage rates climb to the highest level in 2 years[9].

And as I have been pointing out, “after the fact” or ex post narratives as “expensive” barely explains why and how “expensive” came to be. If markets have been rational, as media and their favored analysts presume, then there would hardly be such word as “expensive” or “cheap”. There hardly will be any incidences of “parallel universes” which contrary to the consensus expectations, have been quite common features of financial markets today.

And more interestingly, reports about the contagion from Japan’s twin stock and bond markets crash had only been mentioned in passing or have been mostly muted.

The best explanation I saw as quoted by media[10] was from a multinational domestic based analyst “At the core is higher risk aversion, as evidenced by a blip in 10-year bond yields overnight”

Higher risk aversion signifies a symptom of the current or past developments. People do not just become risk averse for no reason at all or when they wake up on the wrong side of the bed.

The mainstream seems clueless on what has truly been going on.

The Mania in the Philippine Bond Markets

Japan’s twin market crash for me serves as warning signal to the epoch of easy money.

This remains highly relevant today.

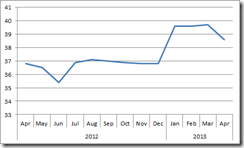

Domestic 10 year yields did spike last Thursday. Such had been the main force to the stock market selloff as I pointed out here[12].

But it is unclear if the surge in yields is going to be a “blip” or a temporary event.

The odds are against such a claim, why?

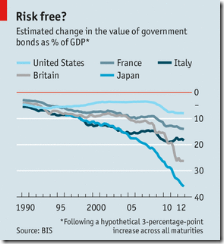

Rising yields have become a global phenomenon.

And as likewise pointed out last week, yields in the US, Germany, France and the crisis stricken PIGS have been ascending.

Does any of the above suggest that higher yields have been a “blip”? And given that global bond yields have been on an upside route, why should the Philippines defy such global trends? Because of the belief in the political “this time is different” nirvana?

Secondly, Asian currencies have been pummeled also from rising yields.

The JP Morgan Bloomberg Asia Dollar index or the ADXY is a trade weighted spot basket of 10 Asian currencies benchmarked against the US dollar[13]. The ADXY has been declining almost in correspondence with the rising yield of Asia.

Asia’s rising yields have even begun to filter into credit concerns.

As the South China Morning Post reported last week[14]:

Borrowers in Asia are seen as the least creditworthy relative to their global peers in almost a year on signs of faltering growth in China.

The Markit iTraxx Asia index of credit-default swaps traded as much as 20 basis points higher than the average of four others from around the world this month, the biggest premium since June, according to data provider CMA.

The Philippine Peso seems headed in tandem with the regional peers (Yahoo Finance). Most of the Peso’s decline has almost been in near synchronicity with the Asian currencies. The falling peso seems to have presaged the huge correction in the Phisix (stockcharts.com)

While the Peso has adjusted to reflect on global trends, the domestic bond markets apparently continues to discount or ignore international developments.

Aside from the global backdrop of rising yields, there is an even more compelling argument why low yields may not last in the Philippines.

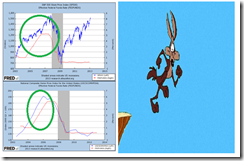

The above charts represent the Philippine 10 year[15] and the US 10 year yield[16]. The yield spread between the domestic and the US bonds have in the norm been about 4-5 basis points. Recently such spread has abruptly collapsed over the last month. This comes as the Philippine yield hit a record low (3.04%!! in May) and as US yields has recently surged (see ellipse). Such has been much about the ballyhooed credit rating upgrades.

As of Friday trading close, the Philippines bond yield closed at 3.54% vis-à-vis the US 2.132%, the spread has narrowed substantially to 1.408 bps.

The Philippines’ 3.54% compares with 10 year yields of our neighbors Thailand’s 3.51%, Malaysia 3.44%, and South Korea 3.1%. This makes the Philippines within their league.

Two factors shaping the collapse of the US-Philippine spread; one frenetic yield chasing dynamic, and the other, the markets see the Philippines as having established a new order.

And unless the financial markets retain such firm conviction or confidence that the Philippine credit profile has reached or attained the standings of our far richer neighbors, then the vastly narrowed Philippine-US spread may or could be an accident waiting to happen via reversion to the mean.

Yes, these are signs of an ongoing mania today in Philippine bonds.

By the way, current Philippines yield suggests that we have significantly economically and financially pulled away from Indonesia whose 10 year yield was last at 6.1% which I am highly doubtful of.

And a risk off environment could be just the apt ingredient for this.

And last week’s yield spike could be a just precursor to the coming mean reversion.

Again a sustained risk OFF environment particularly through higher yields may serve to strengthen or falsify the market’s conviction of the newfound distinction imputed on Philippine bonds—and of the entire spectrum of Philippine assets.

This will also put the recent credit rating upgrades to a crucial test.

Nonetheless a potential bedlam in the local bond markets may hardly signify a conducive environment for the stock market.

The Relationship Between Rising Yields and the Wile E Coyote Moment

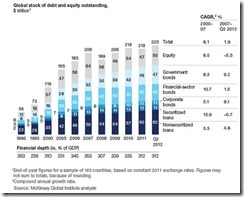

The current rise in global yields may mean one of the following or a combination of the following[17]: the receding stimulative effects of easing policies, growing concerns over shortages of capital, there could be implicit concerns over rising inflation, and finally, increasing concerns over credit risks.

Given that surging yields of major economies seem to have inspired the global bond selloffs I suspect Japan’s crashing bond markets as having been the biggest influence which media consistently tries to suppress.

Rioting JGBs seem to herald the return of the bond vigilantes.

10 year bond yields of Germany (GDBR10 red orange) US (USGG10YR Green) the French (GFRN10 orange) and Japanese (GJGB10 red) appears to have significantly moved higher in conjunction since early May 2013. This was a month after the announced doubling of monetary base, and subsequently, a jump in April’s monetary base affirmed the direction of Bank of Japan’s policies[18].

Rising yield will tend to squeeze out heavily leveraged trades which mean that we should expect heavy volatilities or treacherous market ahead.

Of course some markets like the US may continue to rise even if interest rates ascend. This occurred during the mania phase of pre Lehman bankruptcy boom.

But as I previously discussed[19], rising markets on greater debt accumulation amidst higher interest rates is a recipe for the Wile E. Coyote[20] moment.

Markets can continue to run until it finally discovers that like Wile E. Coyote they have run past the cliff.

This may apply to any markets including the Philippines Phisix or ASEAN.

Finally given that the torrent of bad news which in the past provoked higher markets or “bad news is good news”, the current setting appears to have failed to incite the same expectations and results.

Such difference probably means that markets don’t see sufficient outcomes from current or prospective set of actions from policymakers.

The coming days or sessions will be very interesting.

However I expect monetary authorities to resort to even bigger actions to arrest rising yields—but the consequence may not necessarily revive the risks ON environment.

Trade with utmost caution as market risks seems very high.

[3] NSCB.gov.ph Key Figures PHILIPPINE ECONOMY POSTS 7.8 PERCENT GDP GROWTH May 30, 2013