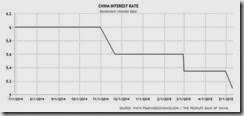

The People’s Bank of China just cut interest rate last Sunday May 10th, for the second time this year.

Apparently the succession of interest rate cuts since 2014 has hardly helped buoyed the real economy. Instead this has only been magnifying credit risks on their financial system.

As I pointed out before, in order to alleviate her intractable debt burden (now an estimated at least 282% of GDP), the Chinese government have contemplated on mimicking Western monetary policies of either Fed QE or ECB style LTRO.

Plans have now turned into action.

China is launching a broad stimulus to help local governments restructure trillions of dollars in debts while prodding banks to lend more, as fresh data added to signs of a worsening slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy.

In a joint directive marked “extra urgent,” China’s Finance Ministry, central bank and top banking regulator laid out a package of measures to jump-start one of the government’s most important economic-rescue initiatives: a debt-for-bond swap program aimed at giving provinces and cities some breathing room in repaying debts.

Central to the directive is a bigger-than-expected plan by the People’s Bank of China that will let commercial banks use local-government bailout bonds they purchase as collateral for all kinds of low-cost loans from the central bank. The goal is to provide Chinese banks with more funds to make new loans. The directive was issued earlier this week to governments across the country and reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

The action marks the latest in a string of measures taken by Beijing to boost economic activity, including three interest-rate cuts since November. But those steps so far have failed to spur new demand, in part because heavily indebted Chinese companies and local governments are struggling with repaying mountains of debt. At the same time, borrowing costs remain high, and low inflation makes it difficult for businesses and consumers alike to service debt. Banks are reluctant to cut lending rates amid higher funding costs and rising defaults.

The sense of urgency to resolve the country’s mounting debt problems is palpable at the government’s topmost decision-making body. The State Council in recent weeks instructed China’s top economic agencies-including the Finance Ministry, the central bank and the China Banking Regulatory Commission-to come up with a plan to help local governments cope with their debt, according to officials with knowledge of the matter.

The attempt at easing debt servicing costs via a debt swap will hardly boost economic growth on a system deeply hobbled by balance sheet impairments, instead what this will do is to buy time and worsen the imbalances (by inflating debt and misallocation of resources).

The Chinese government fails recognize that the consequence of the previous (property) bubble has been to engender widespread balance sheet impairments in the real economy.

So foisting of credit to the financially inhibited economy via intensified easing measures will only signify “pushing on a string” or the inability of monetary policies to entice consumers to borrow and spend.

Instead, the ramifications of such policies will spillover into sectors that has previously had least exposure to credit. And this is what China’s stock market bubble has been about.

Recent credit growth has suffused to the stock market where borrowed money has ballooned and used to hysterically bid up equity prices even as the real economy has been materially deteriorating.

So the Chinese government basically adapts the current therapeutic government standard in dealing with bubbles: Do the same things over and over again and expect different results. Or solve bubble problems by blowing another bubble.

Here is an example how zero bound has only resulted to 'pushing on a string', from the same report:

Meanwhile, Chinese banks also aren’t extending new loans as much as the market expected. In April, banks issued 707.9 billion yuan ($114 billion) in new loans, down from 1.18 trillion yuan in March and below the median 950 billion yuan forecast of 11 economists polled by the Journal. M2, China’s broadest measure of money supply, was up 10.1 per cent at the end of April compared with a year earlier, below the median 12 per cent increase forecast by economists.

The steeper slowdown is forcing policy makers to devise more-aggressive measures to prop up growth if Beijing is going to reach its already-reduced annual growth target, set at 7 per cent for this year, the lowest level in a quarter century. In public, though, the Chinese government maintains a “neutral” monetary-policy stance, as the leadership doesn’t want to appear to be resorting to the old playbook of opening the credit spigot to salvage the economy.

In reality, some economists say, a new stimulus comparable to the $586 billion stimulus package launched in late 2008 is already in the making. Over the past six months, the central bank has cut interest rates three times and twice released the amount of rainy-day reserves set aside by commercial banks with the central bank. In addition, the PBOC has also provided more than $161 billion of funds to banks through a batch of tools.

The path towards larger than 2008 stimulus has been predictable, as I wrote in November 2014

In the past the Chinese government has vehemently denied that this will be in the same amount of the 2008 stimulus at $586 billion. But when one begins to add up spending here and there, injections here and there, these may eventually lead up even more than 2008

So far the recent experiment of inducing banks to buy government bonds has failed.

From the same report:

When the bonds were first offered last month, many banks balked, saying the yields were too low compared with their funding costs. As a result, a number of Chinese regions, including Jiangsu, Anhui and Ningxia, either delayed or planned to put off their bond offerings.

In response to the new directive, the prosperous eastern province of Jiangsu this week relaunched a sale of bonds that it delayed last month. In a statement late Tuesday, Jiangsu said it was scaling back the amount on offer in the first stage, to 52.2 billion yuan, from the 64.8 billion yuan originally planned.

To give banks more incentives to purchase the bonds, the new directive from the Finance Ministry and other agencies requires localities to raise the yields on the bonds, saying the returns shouldn’t be lower than the prevailing Chinese treasury yields. At the same time, according to the order, yields on the new local bonds are capped at 30 per cent above the treasury yields. Currently, one-year Chinese treasury bonds yield about 3.2 per cent, while 10-year treasurys yield 3.5 per cent.

If banks won’t participate, then the PBOC might take the role of lender of last resort. They are likely to absorb most of the debt issuance by local government.

The Chinese government will also try to keep the stock market bubble alive in order to project C-O-N-F-I-D-E-N-C-E, and importantly, as an alternative channel for fund raising (for highly indebted firms to tap equity financing).

The noose on China’s bubble economy tightens.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.bmp)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.bmp)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)