``The economic hardship, of which we had a taste in 1981 and 1982, will be much worse. That in itself is bad enough news, but historically, when a nation debauches its currency international trade breaks down — today 40 percent of international trade is carried out through barter — protectionist sentiments rise — as they have in Congress already — eliciting hostile feelings with our friends. Free-trade alliances break down, breeding strong feelings of nationalism — all conditions that traditionally lead to war; a likely scenario for the 1990s, unless our economic policies and attitudes regarding government are quickly changed.”- Congressman Ron Paul, The Economics of a Free Society

Are Oil and Commodities In A Bubble?

Oil prices dashed to a phenomenal record at $135 per barrel and many have screamed “BUBBLE”!

By definition a bubble means assets or securities priced far from its perceived “fundamentals” or irrationally and impulsively driven by excessive speculation.

The stated reasons for the commodity “bubble”: forced short covering from miscalculated bets, frenetic inventory accumulation by big oil consumers (e.g. airlines) or by nations- such as China use of diesel generation for rescue efforts and for stock piling ahead of the Olympics and worst, alleged collusion to manipulate oil prices such as evidences of government contracted oil tankers holding inventories at seas, rerouting of speculative trades from regulated markets to unregulated markets such as OTC and International Exchange (ICE) and massive jump of investments from pension funds and banks via “Indexed” Speculation.

Any markets always contain certain degrees of speculative element simply because of varying expectations and interests by market participants which are essentially reflected on prices. Some are there to hedge their produce, some are there to profit from short term/momentum trades or take advantage of arbitrage spreads, some are there to profit from long term investments and in cases of a bubble, most will be there simply to be a part of the crowd!

As for the supposed commodity bubble, as we noted previously, while there have been some signs of an emergent bubble, they seem far away from being a Bubble “bubble” as we know of.

Mainstream analysts continue to cavil as they did in early 2006. For us, this represents signs of denial. They think of the financials (with all its present hurdles) and the tech industry as still the vogue place to be and such represents as high quality investments, while the commodity industry has always been condemned and is still relegated to account of low grade cyclical driven speculation. They think past performance will produce the same distribution outcomes.

Under the framework of the psychological cycle operating under a boom-bust or bubble cycle, until the mainstream thinking capitulates, the commodity boom has an enormous room to run.

Yes, we don’t deny that sharp movements of prices assets in one direction should equate to equally dramatic movements to the downside, but what concerns us is the long term trend because trying to time markets for us is a vanity play.

In May of 2005 The Cure Is Worse Than The Disease, we outlined our case for the bullmarket in oil…

``1.

``2. The excess printing of paper monies by the collective governments stoking an inflationary environment,

``3. The OPEC members for nationalizing their respective oil industries thereby misallocating capital investments that led to the present underinvestments,

``4. The Chinese government for adapting a market-based economy (from less than 100,000 cars in 1994 to over 2 million cars 2004),

``5. The US dollar-remimbi peg that accelerated an infrastructure and real estate boom thereby increasing demand for oil,

``6. The war on terror that has disrupted oil supplies,

``7. The Bush administration for the continually loading up the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, and…

``8. The lawyers and environmentalists for increased regulations on explorations and oil refinery requirements.

Have any of the above factors changed? Except for the recent suspension of the stockpiling of the US Strategic Petroleum Reserves, generally all of these fundamentals remain in place.

But we’d like to make some modifications if not additions; for the demand side it’s not only about China but of emerging markets (we are talking about India, Brazil, Russia, Southeast Asia and others representing about 80% of the world’s 6.6 billion population).

Most importantly, we missed one very important variable which ensures the longevity of the commodity cycle….PRICE CONTROLS.

Nonetheless, have oil prices risen enough to impact demand? We doubt so, simply because the market price of oil has not been reflected equally in different countries because of the varying extent of PRICE CONTROLS and if not tax structures encompassing the industry.

Politicization Of The “Oil Bubble”

The recent “bubble” perspective arises from mostly the arguments of the “DEMAND” side.

Just because investments in commodity indices (of which oil makes up a significant share) allegedly surged from $13 billion to $260 billion doesn’t imply that it is in a bubble. Not everything that attracts investments automatically equates to a bubble. Not everything that goes up is a bubble.

Media’s “framing” of information based on relative figures depicts of a bias. And this cognitive bias is known as the Contrast Principle where-we notice difference between things, not absolute measures (changing minds.org). In contrast, the market for derivatives exploded by 44% to $596 TRILLION (and not billions) or to over TEN times the global GDP, yet mainstream seems quiescent about such development. Derivatives are financial instruments or contracts based on the underlying assets such as foreign exchange, interest rates, equities, commodities, inflation indices or even weather predictions.

Why? Because commodity prices impact the real world. And in the real world, people’s lifestyles are affected by commodity price movements, thus have the tendency to be politicized.

And because people refuse to understand the underlying issues, instead they seek for emotionally satisfying terse explanations via melodramatic narratives as seen through heroes and villains. To quote Thomas Sowell ``Voters don't want to hear about impersonal things like supply and demand. They want to hear about how their political heroes will stop the villains from "gouging" them or "exploiting" them with high prices. Moral melodrama is where it's at, politically.”

Nonetheless, when measured relative to its exposure as financial derivatives, according to the Bank of International Settlements, commodities account for only 1.5% (26.5% growth year on year) of the outstanding derivatives in 2007 compared to interest rates 65% (34.83% growth year on year), foreign exchange 9.4% (39.65%), credit default swaps 9.7% (102%), equities 1.4% (13.6%) and others. So as a function of the derivatives markets in relative terms, we don’t see any signs of bubble like performances from commodities.

Yet, commodities cannot be qualified in the same way we evaluate stocks or housing assets, as Ms. Caroline Baum of Bloomberg rightly argues (highlight mine),

``With other asset classes, there are metrics that allow us to quantify the degree to which prices have strayed from their fundamental moorings. Stock prices have an historical relationship with underlying earnings. House prices don't stray too far from their ``earnings'' stream, or rental value.

``With commodities, no such quantifiable ratio exits. Instead, analysts point to verticality, or the rate of price increases in a short period of time; to the fact that open interest in futures contracts dwarfs actual supply; or to the sheer volume of trading.”

In other words, in the absence of any valid metrics to assess if commodities prices have meaningfully careened away from fundamentals, market price actions have been the principal criteria for labeling the activities of oil and commodity prices as a bubble. And market price actions do not tell the whole picture.

This leads us to politicization.

Some have argued to regulators to restrict or limit the participation and speculative positions of institutional investors (pension funds, hedge funds and etc.) into investing in oil and commodity space since they have accounted for a substantial increase in the market capitalization of commodity based index funds.

Backed by circumstantial evidence, the claim is that additional demand from institutional investors represents a form of “hoarding” in the futures market unduly driving up prices. Investors have been able to go around Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) market position limits on commodity acquisitions by swapping with investment banks, who in turn hedges the (total return) swap by buying futures contract. This loophole of allowing swap for hedges has paved way for the unlimited size positioning which concurrently drives up the market caps of commodity index funds.

But cash and futures market signify two distinct functions which essentially refutes such argument, according to the Economist (emphasis mine),

``Yet few bankers agree that speculation has much to do with price rises. For one thing, indexed funds do not actually buy any physical oil, since it is bulky and expensive to store. Instead they buy contracts for future delivery, a few months hence. When the delivery date approaches, they sell their contract to someone who actually needs the oil right away, and then invest the proceeds in more futures. So far from holding oil back from the market, they tend to be big sellers of oil for immediate delivery.

``That is important because it means that there is no hoarding, typically a prerequisite for a speculative bubble. Indeed, as discussed,

This is especially elaborate in the non-storable commodities (livestock and meats). The point is cash markets represents the actual balance of demand and supply and is unlikely to be subjected to massive speculations as alleged to be in contrast to houses or stocks.

Governments Controls The Supply Side Of The Oil Market

Given today’s highly anticipated global economic slowdown, reduced economic activities should have translated to lower demand, thereby pulling down prices. Yet with oil prices having doubled over the past year, pricing signals should have dictated for more supplies, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 courtesy of US Global Investors: Oil Supplies remain Stagnant

But conventional supplies have hardly made a dent to the oil pricing market possibly due to the stagnant production by both OPEC (green line) and Non-OPEC (blue line) even amidst a global economic growth slowdown. With a slim spread between supply and demand, any drop in demand could easily be offset by an equivalent drop in supplies, and if supply falls faster than demand prices then prices will continue to rise!

And importantly, we must not forget that the supply side of the oil market is basically controlled (about 80% of reserves) by governments through national oil companies. Hence, the oil market is NOT a laissez faire or free market, but like rice or food markets, they account as political commodity market functioning under the auspices of nation states.

If oil is indeed in a “bubble” and government intends to pop the “bubble”, then common sense tell us that oil producing governments can simply deliver the coup de grace by offloading its “surplus” oil into the market! No amount of “speculative futures” can withstand the forces of actual supplies crammed into the markets. But has this happened? No.

If the oil markets have NOT been responding to the price signals, it is because the national oil companies, aside from governments themselves, have been responsible for the supply constraints and nobody else.

Underinvestments arising from misallocation of resources, geological restrictions emanating from environmental concerns, legal proscriptions to allow private and or foreign capital for domestic oil explorations and development of the industry (as in Mexico), nationalization of the oil industry (see Figure 2) and capital and technological inhibitions from national governments have all contributed to these imbalances.

Figure 2 Resource Investor/ Guriev, Sergei, Anton Kolotilin, and Konstantin Sonin: High Oil Prices lead to Expropriation or Resource Nationalism

Governments Also Influence Demand Side Of The Oil Market

This by inordinately expanding money and credit intermediation via a loose monetary, price caps and subsidies that has led to widespread smuggling across borders and expanded demand because of profit incentives through price arbitrage and “hoarding” and the amassing of strategic reserves by oil importing countries.

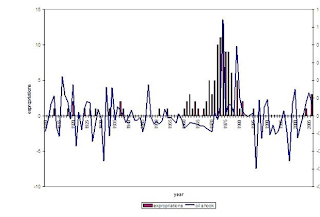

Figure 3: Whiskey and Gunpowder: Money Supply and Oil Prices

Quoting Mr. Mayer (emphasis mine), ``Since January 2001, you can explain the move in the price of oil largely as a function of increasing money supply. As the amount of money grows, the price of oil rises. In fact, almost 87% of the move in the price of oil can be explained by the increase in money supply.

``Basically, $100 per barrel oil is what we would expect to see, given this relationship between the oil price and money supply. Given that we are still in the midst of a credit crisis of sorts, it seems unlikely the Fed will tighten money in any way at all. That leaves a clear path for the price of oil and commodities to continue to rally in nominal terms.”

Since the US is presently engaged in a currency debasing policy as seen with its ongoing “nationalization” of mortgage related losses or whose financial sector have been undergoing a “liquidity” transfusion from the US Federal Reserve, such loose policies have been weighing enormously on the US dollar. The softening economy likewise has contributed to these dollar infirmities.

And since oil prices have been traded mostly in US dollars, the weakening of the US dollar has similarly accounted for a strong inverse correlation with oil prices. In short, a weak dollar-strong oil phenomenon as seen in figure 4.

Figure 4: Stock charts.com: US dollar Index, Euro and Oil

This simply means that given the same rate of a near lockstep association, if the US dollar index (whose basket comprise over 50% weightings by the Euro) continues to weaken, oil prices will most likely continue with its advance or vice versa.

The blue vertical lines, in Figure 4, shows of some notable congruence (interim inflection points) in the prices activities of the US dollar and Oil or Euro.

In addition to US money supplies and the inverse correlation of the US dollar Index and Oil, we have long argued that the US policy of “reflation” are being transmitted to emerging countries via monetary pegs which results to even looser policies leading to a more intense “goods and services” inflation on a globalized scale, see Figure 5.

Figure 5: Economist: Negative Real Rates and A Boom in Global Money Supplies

The chart shows how the world has embarked on a loose monetary policy characterized by a booming money supply (right) mostly in emerging markets and negative real interest rates (left) as measured by short-term yields over nominal GDP growth, where the Economist notes ``So it is worrying that global monetary policy is now at its loosest since the 1970s: the average world real interest rate is negative.”

Loose monetary policies threaten economic growth by price instability or the acceleration of “goods and services” inflation. Again from the Economist (emphasis mine),

``Even if the Fed's interest rate suits the American economy, global interest rates are too low. In turn, the unwarranted stimulus to demand in emerging economies is further pushing up commodity prices; so too is speculative buying by investors seeking higher returns than from bond yields, which are still being depressed by the emerging economies' build-up of reserves. This stokes inflationary pressures in

``Loose money in

So those worried about the pockets of “deflation” in some parts of the world should likewise reckon with how in a global economy, the US Federal Reserve policies as the de facto international currency reserve, has diffused into the emerging markets and how these policies have affected the investing and consumption patterns which has been affecting commodity prices now spreading over to a more pronounced politically sensitive “goods and services” inflation.

Moreover, the investing pattern arising from the growth stories of commodity backed emerging countries have provided further backstop to commodity and commodity based investments.

Next we have price controls.

In an effort to control goods and prices inflation many countries have used price controls or subsidies to buy political stability. Price controls have created arbitrage opportunities within borders, escalating demand for oil to profit from spreads. Such arbitrage opportunities have prompted for incidences of fuel smuggling even within China or in parts of the Asian region and elsewhere.

I even read an account somewhere where some Hong Kong residents have been said to transit to nearby China in order to have their gas tank filled, since gas prices in China is said to be a third of the world market.

These price distorting schemes have helped in the expansion of outsized demand for fuel around the world which has led to elevated oil prices at these levels.

Since rising commodity prices affect the real economy, the clamor for political subsidies will continue to mount.

Commodity bears argue that emerging markets can’t afford such subsidies because it will impair their fiscal positions, thus by lifting subsidies demand will slow.

If political survival is at stake, it is highly questionable if the present set of leaders will undertake unpopular measures that would compromise their positions.

Besides, the other factors possibly influencing the demand supply imbalances in the oil market could due to geopolitical considerations, the structural decline of conventional global oil production (otherwise known as “peak-oil”) or as an unintended consequence from stringent regulations.

If it is also true that government tankers were reportedly kept at seas or seemed to have withheld inventories on the account of expectations for higher prices then it all also goes to show that governments themselves have been engaged in speculations over oil prices.

Needless to say, if oil is in a bubble, then it is obviously a government sponsored bubble!

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)