With the ruble under fire, the Russian central bank mimics ECB Mario Draghi’s “Do whatever it takes” with their own “unlimited intervention” in the hope to stem the faltering currency.

[I’ll argue below that this seems more than about the currency where the latter is only a symptom]

From Bloomberg:

Bank Rossii, which aims to let the ruble trade freely by 2015, bought the most rubles since September 2011 this week to slow the currency’s drop as central banks from Turkey to South Africa raised interest rates to prop up their currencies. The Moscow-based regulator will intervene “without quantitative limitations” until the ruble returns to the target band or the corridor is lifted to its level, it said in a statement on its website, reiterating the present framework for the currency…The central bank has spent $29 billion since May 29 to smooth exchange-rate fluctuations, cutting its gold and forex reserves to $496.7 billion, the lowest level since 2011.

The effect of Bank Rossii’s “unlimited intervention” has been to spike ruble against the USD yesterday. The ruble has been under pressure along with most emerging markets currencies.

The question is will this serve as a temporary patch or will this enough to calm Russia’s financial tantrums? I believe that like her peer, the Turkish central bank's who surprised with a “shock and awe” of dramatically pushing up interest rates, this will have a short term impact.

And like everywhere else, Russia’s currency woes have been manifestations of homegrown credit bubbles rather than fickle foreign money flows as consequence to zero bound rates.

Following the global crisis in 2008 Bank Rossii stepped on the interest rate pedal.

The result? Again like anywhere else, from 2008 loans to the private sector has more than doubled.

This has been accompanied by a near doubling of M2 during the same period.

Part of that credit bubble has been due to Bank Rossii’s foreign currency reserve accumulation. [As a side note, the ruble’s weakness comes amidst a mountain of forex reserves which many mistake as a free lunch to bubbles.]

The build up in foreign exchange reserves has been reflected on the Bank Rossii’s asset growth.

So zero bound rates and Bank Rossii’s forex accumulation has prompted for a credit fueled property boom which supposedly had been one of the “hot” market for real estate in the world in 2013.

While Russia’s housing prices has not reached the pre global crisis of 2007 level (left), housing loans acquired from mostly local institutions have ballooned (middle) to record highs.

And as one would further observe, the gravitation to the real estate boom via housing loans came with declining housing loan rates (right) as charts from Global Property Guide reveal

Zero bound rates has not just been an enticement for the private sector to splurge, the real aim of zero bound rates has been to redistribute of resources from the real economy to the government and to their favored interest groups. This is known as financial repression. Zero bound rates (negative real rates) is just part of the many ways government applies financial repression.

And as proof, while Bank Rossii held rates artificially down, Russia’s local government went into a spending binge.

The Stratfor writes: (bold mine)

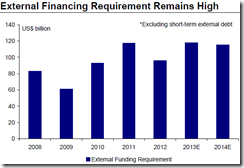

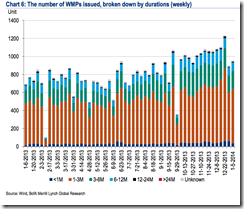

Most of Russia's regional governments have always had some level of debt, but resource-based export revenues have kept it mostly manageable since the 1998 crisis. However, since the 2008-2009 financial crisis, most of the regions' debt has risen by more than 100 percent -- from $35 billion in 2010 to an estimated $78 billion in 2014, and Standard & Poor's has estimated that this will rise to $103 billion in 2015. Russia's overall government debt -- the federal and regional governments combined -- is around $300 billion, or 14 percent of gross domestic product. This is small for a country as large as Russia, but the problem is that so much of the debt is concentrated in the regions, which do not have as many debt reduction tools as the federal government does.Of the 83 regional subjects in Russia, only 20 will be able to keep a budget surplus or a moderate level of debt by 2015, according to Standard & Poor's calculations. This leaves the other 63 regions at risk of needing a federal bailout or defaulting on their debt.Currently, the Russian regions are financing their debt via bank loans, bonds and budget credits (federal loans, for example). Each region has to get federal approval to issue bonds, because regional bonds create more market competition for the federal and business bonds. Most of the banking loans to the regions carry high interest rates and are short term (mostly between two and five years). The federal loans come with much lower rates and longer repayment schedules (mostly between five and 20 years), so naturally federal credits and loans are more attractive for the local governments, though unprofitable for the federal government. The issuance of federal credits or loans to the regions in 2013 was limited; initially, Moscow said it would issue $4.8 billion in new credits to the regions in 2013, but only issued $2.4 billion due to its own budgetary restrictions. This is one contributing factor to the dramatic local-government debt increases.

In terms of federal external currency debt one may note that Russian foreign liabilities jumped by 34% in just two years. So the devaluing ruble will magnify on the Russia’s external credit risks.

Russia’s major exports has been predominantly commodities, particularly oil, the latter accounts for 71% of total exports in 2012. This has allowed Russian government to post a surplus in both the trade balance and her current account. [note the latter graphs I will not show anymore as this post might exceed the 512k size limits, so pls just click on the links]

Despite the huge foreign reserve, current account surpluses and balance of trade account, Russia has been experiencing private capital outflows since 2008 both from the formal and likewise in the informal sector.

The informal sector has been estimated at 50-65% share of the economy where earlier I pointed out that the Russian government attempted to wage war against this sector by putting limits on cash transactions. Russia, according to Global Financial Integrity (GFI), has been the fifth largest victim of illicit capital outflow notes the RT

In my view, such outflows have partly been consequence to the economic and financial repression which has been reflected by the huge informal sector. Some in the formal and informal sector may have sought monetary refuge or safehaven from the grips of Russia’s autocratic government (e.g Cyprus, Cayman Islands). Some perhaps may have sought alternative investments abroad, and some may have been sensing trouble ahead in the Russian economy.

And symptoms of the latter can be seen via last week’s suspension of cash withdrawals for a week by ‘My Bank’ supposedly one of Russia’s top 200 lenders by assets, according to the Zero Hedge.

Some questions: Has this signified the continuing war against the informal economy? But if so, why limit to My Bank? Or has this been signs of a Russian bank in serious trouble? If the latter, has the problems of My Bank been large enough for the Bank Rossii to stay at the sidelines and compel My Bank to take her own measures? Will this not send signals to depositors and investors that Russia’s banking system may be in dire predicament? Could the Bank Rossi’s “unlimited intervention” have been really directed to calm the banking sector or forestall a depositor stampede/bank run?

Interesting twist of events.

In other words, instead of the mainstream’s impression that today’s emerging market rout has been led by foreign money, in Russia’s conditions, the weak ruble and the spike in bond yields 10 year Russian treasuries may have been mostly an exodus of resident money.

And this Wall Street Journal article seems to back my suspicion “High capital outflows have become a sore point in Russia in recent years, with critics saying official corruption is hampering the investment climate and driving money out of the country. The central bank considers debt redemption, dividends paid to foreign shareholders, Russian residents buying foreign currencies, and mergers and acquisitions as capital outflow.”

Bottom line:

One huge foreign reserves, and surpluses in current account and balance of trade account serve as no free pass to bubbles. Russia’s case is just one example

Two contra popular wisdom, it doesn’t take foreign money to pull the trigger for a bust to occur as in the case of Japan in the 1990. While there has hardly been a full credit bust in Russia yet, developing events seem to indicate that Russia’s credit bubble may have already reached its maximum elasticity point (in the face of rising bond yields). And the bubble bust will likely be sparked by a capital flight from resident depositors and investors.

Russia’s plight seems far from over.