Statistical analysis without establishing the meaning of a particular economic activity cannot tell us what is going on in the world of human beings. All the statistical analysis can do is to describe things; it cannot explain, however, why people are doing what they are doing. Without the knowledge that human actions are purposeful, it is not possible to make sense out of historical data—Dr Frank Shostak

In this issue

2023 PSE Stock Market

Accounts Hit a Record 1.9 million as Active Accounts Fall to All-Time Lows, BSP

Chief on Foreign Money "I Do Not Know Why They Do Not Like Us"

I. PSE’s Stock Market Accounts Hit a Record 1.9 million

II. Differentiating Growth Rate from a Growth Trend, The Digitalization of the Philippine Stock Market

III. It is the Active Accounts that Matter: Reaching an All-Time Low!

IV. PSEi 30’s Bear Market: Reduced Participation Rate, and Diminishing Volume; Age Distribution of Participants Suggests a Worrisome Trend!

V. Stock Market Doldrums

Brought About by Savings Drought Manifested in Banking Data and Market Manipulation

VI. 2024 5-Month Volume

and Market Breadth Exhibits Oversold Conditions

VII. Symptoms of Market

Distortions and Inefficiencies: An Examination of Market Dominance by the Top

10 Brokers and PSEi 30's Top 5 Issues

VIII. BSP Chief Remolona

on Foreign Money: "I Do Not Know Why They Do Not Like Us"

2023 PSE Stock Market Accounts Hit a Record 1.9 million as Active Accounts Fall to All-Time Lows, BSP Chief on Foreign Money "I Do Not Know Why They Do Not Like Us"

The PSE registered an 11.3% growth in stock market accounts in 2023, but active accounts fell to an all-time low, supported by a dearth in volume. The BSP Chief questions why foreign money continues to elude the Philippines, highlighting the challenge facing local investors.

I. PSE’s Stock Market Accounts Hit a Record 1.9 million

Inquirer.net, May 29, 2024: Stock market accounts rose 11.3 percent to 1.906 million in 2023 from 1.7 million in the previous year, according to the Philippine Stock Exchange’s (PSE) annual Stock Market Investor Profile report. The growth was mainly due to new accounts opened through the GStocksPH platform, which also pushed the share of online accounts to 80 percent of total stock market accounts. Online accounts stood at 1,525,768 as of end-2023, up 21.2 percent or 266,861 accounts.

Figure 1The headlines provide the good news: a surge in new stock market accounts. This surge was highlighted by PSE's infographics, which emphasized "growth." (Figure 1, topmost table)

We'll take it further.

In the context of peso nominal gains, the 193,285 increase in 2023 marked the largest after 2021 and 2018. (Figure 1, middle chart)

The upsurge in new accounts has increased the stock market's penetration level to a record 1.7% of the population (using GDP calculations). (Figure 1, lowest graph)

Or, this represents an unprecedented 2.44% of the population over 15 years old and 3.7% of the labor force (PSA labor survey).

However, there's a catch. If so, why has the PSE's volume been falling?

II. Differentiating Growth Rate from a Growth Trend, The Digitalization of the Philippine Stock Market

Let's dig deeper to understand the underlying factors.

The reason is that new accounts are only one part of the equation.

Figure 2

First, the headlines only reveal the growth rate, but they don't reveal the growth trend. The fact is that since peaking in 2018, the growth trend has been on a decline. (Figure 2, topmost chart)

2023 could be seen as a countercyclical bounce, possibly driven by a shift to a mobile application trading platform similar to the US Robinhood Markets.

As evidence of the marked transition towards a digital economy, the share of online trading hit an unmatched 80% of the total. This growth was accompanied by a 21.2% YoY increase. (Figure 2, middle image)

In contrast, traditional brick-and-mortar accounts saw a significant decline in 2023. This decline was marked by a contraction of -16.2% YoY and a share drop from 26.5% to 19.95%. (Figure 2, lowest graph)

This shift towards online trading is reflective of the industry's broader trend towards digitalization, which has been driving the growth of new accounts.

As we explore this trend further, we will delve into its implications for the sell-side industry's future.

III. It is the Active Accounts that Matter: Reaching an All-Time Low!

Returning to the paradox of the record new accounts amidst declining volume, a more pertinent metric is "active accounts."

Figure 3

Consider this: while the total number of active accounts represents 17.6%, online accounts make up 19.3%. This means that in total, there are only 335,459 active accounts—a historic low! (Figure 3, topmost table and middle window)

Interestingly, the retail segment experienced a lesser decline compared to institutional accounts. Retail active accounts dropped from 20.1% to 17.6% of the total, while institutional accounts plummeted from 23.7% to 20.5%. (Figure 3, lowest graph)

In nominal figures, retail accounts decreased by 2.2%, while institutional accounts saw a significant dive of 22.53%

The PSE numbers didn’t specify whether the new accounts were included in this year’s active accounts or if the active accounts represented last year’s total numbers.

However, if it's the former case, then nearly 58% of the new accounts are part of the active ones! If this holds true, will they, like their predecessors, fade soon?

IV. PSEi 30’s Bear Market: Reduced Participation Rate, and Diminishing Volume; Age Distribution of Participants Suggests a Worrisome Trend!

Figure 4

Like day follows night, the declining participation rate has characterized the PSEi 30’s bear market in disguise.

Since its climax in 2017, the PSEi 30's (end of year) downtrend has resonated with the corrosion of the growth of total accounts. 2023’s 11.3% marked the second-lowest YoY growth rate since 2017. Notably, this growth rate was achieved from a very low base. (Figure 4, topmost chart)

The decline in participation rates can also be attributed to the poor returns from investing in the PSE, as many investors became "long only," and wary of taking risks after experiencing prolonged losses. (Figure 4, middle pane)

Moreover, diminishing volume has accompanied the PSEi’s 30 bear market. (Figure 4, lowest diagram)

Figure 5

Interestingly, among age groups, while millennials suffered the most decline in participation, followed by Gen X, it was the seniors who provided the most growth in total accounts. Senior accounts soared from 10.8% to 14.8%! (Figure 5, topmost table)

That online accounts dominated the total was also manifested in the age distribution. The boomers, who in the past years (except 2021) have shied away from online accounts, became the largest growth sector, surging from 5% to 10.9%. (Figure 5, second to the highest table)

On the other hand, millennials, who composed the bulk of the age grouping, endured a substantial contraction, from 55.7% to 49%! Part of Gen Z helped in the increase from 20.8% to 21.5%.

This reveals a lot about income and savings conditions. It likely exposes that the 30-44 age grouping must have endured most from the decaying conditions in real income and savings, hence their participation pullback in the PSE.

It also manifests that under the current high inflation environment, the age group with the most savings, the seniors or boomers, were driven to scour for yields in the stock market. They braved the challenges of learning to use digital platforms for trading to gamble.

The thing is, a savings drought, which brought about the PSEi 30’s bear market, has been manifested by the decaying gross volume or turnover, which reverberated with the decrease in the participation rate.

Needless to say, a restoration of savings should anchor a comeback of a healthy bull market—similar to the pre-2013 era. Without it, everything else represents a juvenile belief in unicorns, the tooth fairy, or castles in the sky or false optimism and unsustainable trends.

V. Stock Market Doldrums Brought About by Savings Drought Manifested in Banking Data and Market Manipulation

Symptoms of the deterioration of savings have similarly been manifested in the banking system. The 10-year decay of the bank’s deposit liabilities or cash-to-deposit ratio reveals a lot about inflation and malinvestments via asset bubbles ravaging savings. (Figure 5, second to the lowest and lowest charts)

Figure 6

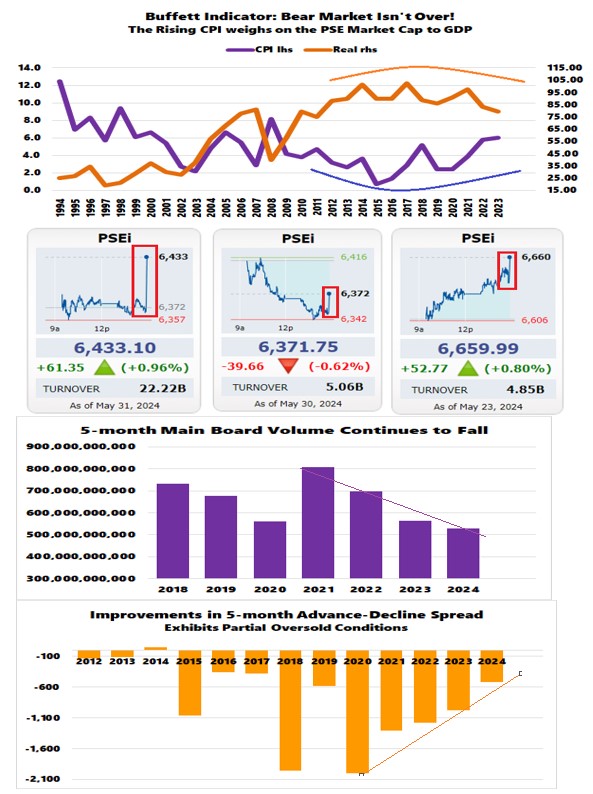

The Warren Buffett Indicator—market cap divided by the GDP—also exhibits this deviation. The PSEi 30’s declining ratio demonstrates the bear market in motion. (Figure 6, topmost graph)

Additionally, since debt has anchored private and public activities, it bloats the GDP. Therefore, the overstated GDP performance inflates this market cap-to-GDP ratio. Furthermore, the rising Consumer Price Index (CPI) has coincided with the decline of the ratio, indicating that inflation has been a major hindrance (a menace) to the financial economy.

That’s not all.

Massive "marking the close" pumps and dumps have contributed to the intensifying mispricing of the local stock market. Basic economics tell us that price controls lead to either shortages or gluts. The same holds true for the stock market.

Friday’s massive 1% "mark the close" pump came about from the top 10 brokers who were responsible for 80% of the transactions. End session pumps and dumps have become a common feature in the PSEi 30. (Figure 6, second to the highest charts)

The essence of the stock market is its pricing mechanism in the titles to capital.

The gaming of the index, thereby, percolates or radiates to the economy via misallocations of capital brought about by these pricing distortions. It exacerbates malinvestments from monetary policies and other forms of interventions—which of course, would be revealed over time.

At the very least, all these contribute to the erosion of savings.

VI. 2024 5-Month Volume and Market Breadth Exhibits Oversold Conditions

Many have come to the conclusion that the PSE’s turnover has been improving.

That may be partially true. While May’s volume jumped 25.6% YoY—helped by the Month-end marking the close pump—following April’s 71.12% surge, the 5-month aggregate turnover declined 6.2% from last year. (Figure 6, second to the lowest image)

The two-month surge has barely offset the declines of the early months.

Sure, market breadth has exhibited signs of improvement. The 2024 5-month advance-decline spread marks the lowest since 2019. (Figure 6, lowest diagram)

In a nutshell, despite the PSE’s cheerleading via the headline numbers, the depressed turnover, and low participation rates backed by improving partial market internals exhibit oversold conditions.

VII. Symptoms of Market Distortions and Inefficiencies: An Examination of Market Dominance by the Top 10 Brokers and PSEi 30's Top 5 Issues"

Still, the current environment has been a product of loose financial conditions, which means more pressure on the PSE should conditions tighten.

However, the ever-dithering BSP would likely tolerate or gamble with "higher for longer" inflation than tighten monetary conditions due to unsustainable debt conditions.

Furthermore, the sluggish turnover also implies increasing stress on the sell-side (brokerage) industry. According to the PSE, there are 122 trading participants, 37 of which have online platforms.

But here's the rub: the top 10 brokers capture a vast majority of daily transactions. Most of them represent institutional brokers—possibly accounts of banks and other financial institutions.

Figure 7

Last week, the average soared to 63.4%, mainly due to Friday’s mark-the-close pump, where the top 10 brokers accounted for a staggering 80% of the Php 22 billion trade! (Figure 7, topmost visual)

The limited distribution of transactions to a select number of brokers highlights the extent of concentration of activities or "market dominance" in the stock market, which is equally reflected in the dispersion of weightings in the PSEI 30’s free-float market capitalization.

The aggregate free-float cap of the top 5 issues hit a record 51.92% last April 19th! (Figure 7, second to the highest image)

These phenomena are all manifestations of distortions: market inefficiencies, imbalances and irregularities.

As an aside, financial services accounted for 15% share of the retail accounts in 2023. This suggests that a substantial share of direct retail transactions involves those who sell "financial services" (buy and sell side), potentially leading to many principal-agent problems.

By inference, our guess is that many traditional retail brokers are on the threshold of survival.

Ironically, the PSE brags about the headline numbers of stock market accounts, while there appear to be ZERO takers of its short-selling program since its inception.

Also, since the start of its Volume Weighted Average Price (VWAP) trading program last March 1, total transactions amounted to only Php 415.435 million.

These new programs have had little or no impact on the sell-side industry.

Yet, the BSP and PSE’s policies will continue to haunt savers while applying pressure to the sell-side industry.

In my humble opinion, the PSE aims to consolidate the brokerage industry by reducing the number of brokers (or competition) and favoring a few larger players—to increase its control.

VIII. BSP Chief Remolona on Foreign Money: "I Do Not Know Why They Do Not Like Us"

In a surprising twist, the BSP chief expressed concerns about the lack of depth in the PSE, citing the limited foreign participation as a key factor contributing to its lack of international recognition. (bold mine)

And finally, we have our missing portfolio flows. We used to fear portfolio flows because we saw them as hot money. They come in and leave at the first sign of trouble.

But these days, they are not so scary. In the first place, they are so negligible these days; they can come in and out, and it will not matter.

But the big thing is the game has changed; the intent is not into active investment anymore; it is in passive investment. Passive means you buy the index. At least at the core of your portfolio, you need an index. Maybe you can play around on the sides of your portfolio, but the core has to be an index.

Huge trillions of dollars are now flowing into the major equity indices, global equity indices, and the major primary bond indices. I think we are in a few indices. We talked to Vanguard, and they said we are about 0.1 percent of their bond index.

But we are not in any major equity indices, BlackRock or State Street. We do not know why; people say it is our withholding taxes, but we are not sure what is going on.

Bakit hindi tayo kasali? The smaller markets are in these indices. Colombia is in that index. Etsepuwera tayo, hindi tayo kasali. I do not know why they do not like us. (Remolina, 2024)

This lack of understanding (incredible cluelessness) and the tendency to blame foreign investors for the country's financial issues is striking.

Yet, as an old Wall Street Maxim goes, "Money goes where it is treated best."

The Philippine authorities and private regulators should reflect or self-examine on whether they have been creating an attractive environment for investors or if they have been providing money with a red-carpet treatment or not. The Philippine Stock Exchange is a monopoly with self-regulatory powers.

The questions to ask: has the BSP’s inflation targeting regime, a "trickle-down policy, " successfully diffused to build up savings for the average Pedro and Maria?

Or has it supported the debt-financed Keynesian "build and they will come" policy framework benefiting the elites and the government while consuming the savings of the general populace through the economic maladjustments as evidenced by the record savings-investment gapsavings-investment gap?

In essence, have their policies been supportive of local savers and conducive to the industry?

The crux: If they can’t draw local savers into the capital markets (bonds and stocks), why would foreigners follow?

Foreign portfolio flows into the Philippines have declined significantly since 2013. (Figure 7, second to the lowest graph)

The Philippine bond market is one of the smallest in Asia, which is likely why foreign flows have been limited. (Figure 7, lowest chart)

Then why blame foreigners for "not liking" the Philippines?

____

References

Dr Frank Shostak, Can Data by Itself Inform Us about the Real World? May 27, 2024, Mises.org

Philippine Stock Exchange, STOCK MARKET INVESTOR PROFILE 2023, May 2024, PSE.com.ph

Eli M Remolona: The challenges we face at Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, Speech by Mr Eli M Remolona, Jr, Governor of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP, the central bank of the Philippines), at the General Membership Meeting of the Financial Executives Institute of the Philippines, Makati City, 6 March 2024. April 16, 2024, Bank for the International Settlements